The Space of Kafka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

THE POLITICS of CATASTROPHE in the ART of JOHN MARTIN, FRANCIS DANBY, and DAVID ROBERTS by Christopher J

APOCALYPTIC PROGRESS: THE POLITICS OF CATASTROPHE IN THE ART OF JOHN MARTIN, FRANCIS DANBY, AND DAVID ROBERTS By Christopher James Coltrin A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History of Art) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Susan L. Siegfried, Chair Professor Alexander D. Potts Associate Professor Howard G. Lay Associate Professor Lucy Hartley ©Christopher James Coltrin 2011 For Elizabeth ii Acknowledgements This dissertation represents the culmination of hundreds of people and thousands of hours spent on my behalf throughout the course of my life. From the individuals who provided the initial seeds of inspiration that fostered my general love of learning, to the scholars who helped with the very specific job of crafting of my argument, I have been the fortunate recipient of many gifts of goodness. In retrospect, it would be both inaccurate and arrogant for me to claim anything more than a minor role in producing this dissertation. Despite the cliché, the individuals that I am most deeply indebted to are my two devoted parents. Both my mother and father spent the majority of their lives setting aside their personal interests to satisfy those of their children. The love, stability, and support that I received from them as a child, and that I continue to receive today, have always been unconditional. When I chose to pursue academic interests that seemingly lead into professional oblivion, I probably should have questioned what my parents would think about my choice, but I never did. Not because their opinions didn‟t matter to me, but because I knew that they would support me regardless. -

Zilcosky on Zischler, 'Kafka Goes to the Movies'

H-German Zilcosky on Zischler, 'Kafka Goes to the Movies' Review published on Monday, September 1, 2003 Hanns Zischler. Kafka Goes to the Movies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003. xiv + 143 pp. $30.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-226-98671-5. Reviewed by John Zilcosky (Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Toronto.) Published on H-German (September, 2003) Boundless Entertainment? Boundless Entertainment? There are at least three ways to read this book, which first appeared as Kafka geht ins Kino in 1996: as a discussion of the significance of film and new media for Kafka's writing; as a mission of cultural recovery, including never-before-published archival film footage; and as a "mad and beautiful project" (Paul Auster) that combines autobiography, detective novel, art collage, and literary scholarship. In the first sense the book fails, but in the other two it succeeds in surprising, original ways. To begin with the last point: Zischler's book opens unusually, with a series of images including a spectacular 1914 photograph of Prague's Bio Lucerna cinema. The small "1" in the bottom right corner alerts us to the fact that this photograph has a footnote, and we thus begin Zischler's strange readerly trip. We start flipping pages, like the attendant Kafka noticed at the Kaiser Panorama, from front to back, image to word, and vice-versa. Zischler's intellectual collage develops toward metaphysical detective fiction--we can see why Auster liked it!--when the main text opens: "I was working on a television movie about Kafka in 1978 when I first came across the notes on the cinema in his early diaries and letters." This leisurely curiosity of the actor in a Kafka movie eventually developed into an obsession: into "regular detective work" that took Zischler on the route of Kafka's early bachelor trips with Max Brod (Munich, Milan, Paris) in search of old cinemas and films. -

Kafka's Travels

Kafka’s Travels Kafka’s Travels Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing John Zilcosky palgrave macmillan KAFKA’S TRAVELS Copyright © John Zilcosky, 2003. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published 2003 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York,N.Y.10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS. Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-4039-6767-1 ISBN 978-1-137-07637-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-137-07637-3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zilcosky, John. Kafka’s travels : exoticism, colonialism, and the traffic of writing / John Zilcosky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-312-23281-8 1. Kafka, Franz, 1883–1924—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Kafka, Franz, 1883–1924—Journeys. I. Title. PT2621.A26 Z36 2002 833’.912—dc21 2002029082 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design by Letra Libre, Inc. First edition: February 2003 10987654321 To my parents and the memory of Charles Bernheimer Contents Acknowledgements ix List -

Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing by John Zilcosky

UC Berkeley TRANSIT Title BOOK REVIEW: Kafka’s Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing by John Zilcosky Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/45539222 Journal TRANSIT, 2(1) Author Gerhardt, Christina Publication Date 2005 DOI 10.5070/T721009704 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California John Zilcosky. Kafka’s Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. Pp. xvi, 289. Cloth $79.95. Paper $26.95. As much a meditation on the relationship among Franz Kafka’s writing, travel and travel writing, and concomitant subject matters – such as fin de siècle exoticism, colonialism and imperialism, as well as railroad expansions, travel guides and adventure books – Zilcosky’s well-researched volume Kafka’s Travels also considers the arrival and role of technologies as varied as photography, film, telephones, and telegrams vis-à-vis Kafkas’ writings. Kafka, as Zilcosky tells us on the opening page of his book, “never moved from Prague until the final year of his life and, yes, his travels were limited to short trips throughout Europe.” Why then a study of Kafka’s Travels? Because not only was Kafka an avid reader of books about travel, such as colonial travel stories, but he also avidly traveled, as Zilcosky convincingly argues, through his texts, both the ones he read and the ones he wrote. Zilcosky analyzes the well-known novels America, The Trial, and The Castle, and short stories, such as The Metamorphosis, “In the Penal Colony,” and “The Hunter Gracchus.” He also sheds new light on Kafka’s Letters to Milena. -

Kafka in Kanada Von Lara Pehar

Kafka-Atlas Kafka in Kanada von Lara Pehar Matamorphosis-Ausstellung beim Nuit-Blanche-Festival Porträt Innerhalb des kanadischen akademischen Bereiches ist Franz Kafka ein etablierter kanonischer Autor. Seine Werke werden in unterschiedlichen Disziplinen erforscht und gelehrt: in der Germanistik, und der Slawistik, und auch in vergleichender Literaturwissenschaft, sowohl in der Judaistik, als auch in Diasporastudien und in Jura. Auch im kulturellen Leben Kanadas nimmt der Prager Autor eine ikonische Funktion als Philosoph ein. Die berühmtesten seiner Werke wurden für die Bühne adaptiert oder zu Hörspielen verarbeitet; politisch motivierte Filme und künstlerische Projekte betten die bürokratische Aspekte seiner Werke ein und heben die subjektive Erfahrung von Kafkas Helden hervor. kafkaesk „Kafkaesque“ ist ein sehr häufig verwendeter Begriff in der Umgangssprache und insbesondere im Journalismus. Ein Eintrag dafür erscheint sogar im Canadian Oxford Dictionary, was den enormen Symbolwert Kafkas in Kanada vermuten lässt. Die Assoziationen des Attributs „kafkaesk“ sind auch in Kanada vielfältig: bedrohlich, grotesk, rätselhaft, paradox, usw. Dennoch wird seine bürokratische Dimension am meisten wahrgenommen. In den Medien kommt der Begriff in den letzten Jahren immer häufiger zum Einsatz, besonders im Zusammenhang mit der Politik der kanadischen Regierung bezüglich Staatsbürgerschaft, Einwanderung und Überwachung terroristischer Aktivitäten im Lande als Folge der Terroranschläge am 11. September 2001. Diese Tendenz veranschaulichen die Schlagzeilen in den Zeitungen: „After Kafkaesque hunt, Indian status and citizenship both out of reach for desperate Ontario mom“ (The National Post, 25. Juli, 2013); „Kafkaesque bureaucracy denies citizenship to legitimate Canadians“ (The Vancouver Observer, 2. September, 2012); „Canada’s K: Mohammad Mahjoub’s Kafkaesque ordeal“ (Pacific Free Press, 24. Oktober, 2013); „Campaign against ‚Kafkaesque justice’ in Canada“ (Centre for Media Alternatives Quebec, 12. -

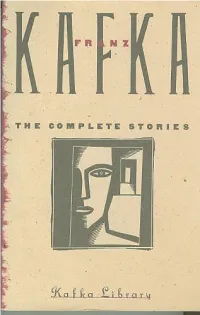

Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Back Cover: "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. The foreword by John Updike was originally published in The New Yorker. -

Maurice Blanchot in the Space of Literature

The Space of Literature Maurice Blanchot Translated, with an Introduction, by Ann Smock University of Nebraska Press Lincoln , London -iii- Introduction and English-language translation © 1982 by the University of Nebraska Press Originally published in France as L'Espace littéraire , © Éditions Gallimard, 1955 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First paperback printing: 1989 Most recent printing indicated by the first digit below: 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Blanchot, Maurice. The space of literature. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Literature--Philosophy. 2. Creation (Literary, artistic, etc.) I. Title. PN45.B42413 801 82-2062 ISBN 0-8032-1166-X AACR2 ISBN 0-8032-6092-X (pbk.) ∞ + -iv- A book, even a fragmentary one, has a center which attracts it. This center if not fixed, but is displaced by the pressure of the book and circumstances of its composition. Yet it is also a fixed center which, if it is genuine, displaces itself, while remaining the same and becoming always more central, more hidden, more uncertain and more imperious. He who writes the book writes it out of desire for this center and out of ignorance. The feeling of having touched it can very well be only the illusion of having reached it. When the book in question is one whose purpose is to elucidate, there is a kind of methodological good faith in stating toward what point it seems to be directed: here, toward the pages entitled "Orpheus' Gaze." -v- [This page intentionally left blank.] -vi- Contents Translator's Introduction 1 The Essential Solitude 19 Approaching Literature's Space 35 Mallarmé's Experience 38 The Work's Space and Its Demand 49 The Work and the Errant Word 51 Kafka and the Work's Demand 57 The Work and Death's Space 85 Death as Possibility 87 The Igitur Experience 108 Rilke and Death's Demand : 120 1. -

Triendl on Zilcosky, 'Kafka's Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing'

H-Travel Triendl on Zilcosky, 'Kafka's Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing' Review published on Tuesday, June 1, 2004 John Zilcosky. Kafka's Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. xvi + 289 pp. $59.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-312-23281-8. Reviewed by Mirjam Triendl (Department for Jewish History and Culture, University of Munich) Published on H-Travel (June, 2004) With the Finger across the Map With his recent probing on Kafka's Travels, John Zilcosky adds an unusual perspective to the many publications dealing with the figure of Franz Kafka. Within the context of postcolonial thinking, this book provides a close reading of Kafka's work as metaphorical travel literature and on Kafka himself as an imagined traveler. Beyond the field of literary science, this study may broaden not only the history of travel writing itself but also the history of travel in general. Admittedly, this review reflects a very idiosyncratic reading of the book: as a relative "outsider" within the field, the following thoughts will also mirror my own background--the history of travel within a Jewish cultural context. John Zilcosky understands Kafka as an "avid textual traveler," taking up a phrase introduced by Rolf Goebel, "a voyager who traveled as a reader and a writer despite (or because of) his personal stasis" (p. 1). Starting out from a postcard Kafka wrote to his first fiance, Felice Bauer, Zilcosky discovers the "otherworldly poet of alienation" as an enthusiastic reader of popular colonial travel stories-- Schaffenstein's Little Green Books (p. -

Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing by John

John Zilcosky. Kafka’s Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. Pp. xvi, 289. Cloth $79.95. Paper $26.95. As much a meditation on the relationship among Franz Kafka’s writing, travel and travel writing, and concomitant subject matters – such as fin de siècle exoticism, colonialism and imperialism, as well as railroad expansions, travel guides and adventure books – Zilcosky’s well-researched volume Kafka’s Travels also considers the arrival and role of technologies as varied as photography, film, telephones, and telegrams vis-à-vis Kafkas’ writings. Kafka, as Zilcosky tells us on the opening page of his book, “never moved from Prague until the final year of his life and, yes, his travels were limited to short trips throughout Europe.” Why then a study of Kafka’s Travels? Because not only was Kafka an avid reader of books about travel, such as colonial travel stories, but he also avidly traveled, as Zilcosky convincingly argues, through his texts, both the ones he read and the ones he wrote. Zilcosky analyzes the well-known novels America, The Trial, and The Castle, and short stories, such as The Metamorphosis, “In the Penal Colony,” and “The Hunter Gracchus.” He also sheds new light on Kafka’s Letters to Milena. Additionally, Zilcosky brings the reader’s attention to little known writings of Kafka. For example, he devotes the first chapter to the early and unfinished travel novel Richard and Samuel: A Short Journey through Central European Regions, which Kafka and Max Brod began co-authoring during their 1911 trip through central and western Europe. -

The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record Volume Li, 1920

THEEW N YORK Genealogical a nd Biographical Record. DEVOTEDO T THE INTERESTS OF AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND BIOGRAPHY. ISSUED Q UARTERLY. VOLUME L I, 1920 PUBLISHED B Y THE NEW Y ORK GENEALOGICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY 226 West 58TH Street, New York. Publication C ommittee : HOPPER STRIKER MOTT, Editor. JOHN R. TOTTEN, Financial Editor. JOHN E DWIN STILLWELL, M. D. TOBIAS A. WRIGHT. ROVDEN W OODWARD VOSBURGH. REV. S. WARD RIGHTER. CAPT. R ICHARD HENRY GREENE. MRS. ROBERT D. BRISTOL. RICHARD S CHERMERHORN, JR. WILLIAM ALFRED ROBBINS INDEXF O SUBJECTS. Accessions t o Society's Library; not Accessions t o Society's Library; not reviewed — reviewed {Continued) American Historical Society, Re Essex, Mass., Quarterly Court of, port for 1916, Vols. I and II, Records and Files, Vol. VII., 100 280 American R evolution, National Ffoster, T homas, Photographic Society Sons of, Report for copy of deed by him dated 1919, 280 March 3. 1674-5, 280 Andover, N . H., History of the Fleming, O wasco Outlet, Cayuga Town of, 100 Co., N. Y., Records of the Re .Athens, N Y., First Reformed formed Protestant Dutch Church, Report of, 280 Church, typewritten manu Auburn D ale, Mass., Early Days script, 100 in, (1665-1870), 100 Florida, M ontgomery Co., N. Y., Beanes, D r. William, Biographi Records of the United Presby cal Sketch of, 172 terian Church, typewritten man Belfast, M aine, Vital Records to uscript, 100 1802, Vol. II, 172 French G enealogical Associa Brookins F amilies, a brief sketch tion, Letters and Papers of, of, 280 100 Brown F amily Chart, manuscript, Genealogies, A merican and Eng 100 lish, List of, in the Library of Cambridge, M ass., Kitty years a Congress, Washington, D. -

Naturalizing Biblical Hermeneutics a Case for Grounding Hermeneutical Theory in the Sociocognitive Sciences

Language and Culture Archives Naturalizing Biblical Hermeneutics A Case for Grounding Hermeneutical Theory in the Sociocognitive Sciences Richard Brown ©2010, Richard Brown License This document is part of the SIL International Language and Culture Archives. It is shared ‘as is’ in order to make the content available under a Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivativeWorks (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). More resources are available at: www.sil.org/resources/language-culture-archives. Naturalizing Biblical Hermeneutics A Case for Grounding Hermeneutical Theory in the Sociocognitive Sciences A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Richard Brown Brunel University Supervised at London School of Theology an Associated Institution of Brunel University 1 August 2010 Naturalizing Biblical Hermeneutics Abstract Most theories of biblical hermeneutics were developed within literary and philosophical frameworks that were antipsychologistic. Without a grounding in empirical research, hermeneutical theories have been largely intuitive, with little empirical criteria for substantiating their claims or arbitrating among differing interpretations. The one exception has been those approaches that utilized linguistics and discourse analysis, but even these were conducted in a structuralist framework that was antipsychologistic. In the last fifty years, however, the so-called ‘cognitive revolution’ has turned this around in most disciplines in a broad movement called cognitive science. Relevant to hermeneutics is the fact that research in various branches of cognitive science has led to a wealth of studies that shed light on the natural cognitive processes involved when people interpret one another and compose written communications. Since meaning is a cognitive phenomenon and the interpretation of others is a sociocognitive activity, it would seem reasonable to naturalize hermeneutical theory by grounding it in the empirical sociocognitive sciences.