Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Delaware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cefn Viaduct.Pdf

The Cefn Viaduct Cefn Mawr Viaduct The Chester and Shrewsbury railway runs at the eastern end of the Vale of Llangollen, beyond the parish boundary, passing through Cefn Mawr on route from Chester to Shrewsbury. It is carried over the River Dee by a stupendous viaduct, half a mile down stream from the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct. It measures one thousand five hundred and eight feet in length, and stands one hundred and forty-seven feet above the level of the river. The structure is supported by nineteen arches with sixty foot spans. In 1845 rival schemes were put forward for railway lines to join Chester with Shrewsbury. Promoters of the plan to link Shrewsbury to Chester via Ruabon had to work quickly to get their scheme moving. Instructions for the notices and plans were only given on the 7th November and they had to be deposited with the clerk of Peace by the 30th November 1845. Hostility from objecting landowners meant that Robertson had to survey the land by night. One irate squire expressed a wish that someone would 'throw Robertson and his theodolite into the canal'. Henry Robertson told a Parliamentary Committee of the advantage of providing a railway line that would open up coalfields of Ruabon and Wrexham to markets at Chester, Birkenhead and Liverpool in the north and to Shrewsbury and other Shropshire towns on the south side. The Parliamentary Committee agreed with him and the bill received Royal Assent on 30th June 1845. The Shrewsbury and Chester Railway Company made good progress with construction work and the line to Ruabon from the north was opened in November 1846. -

Normanhurst and the Brassey Family

NORMANHURST AND THE BRASSEY FAMILY Today, perhaps, it is only architects whose names live with their engineered creations. Those who build bridges, roads and railways are hidden within the corporations responsible, but in the nineteenth century they could be national heroes. They could certainly amass considerable wealth, even if they faced remarkable risks in obtaining it. One of the – perhaps the greatest – was the first Thomas Brassey. Brassey was probably the most successful of the contractors, was called a European power, through whose accounts more flowed in a year than through the treasuries of a dozen duchies and principalities, but he was such a power only with his navvies. Brassey's work took him and his railway business across the world, from France to Spain, Italy, Norway, what is now Poland, the Crimea, Canada, Australia, India and South America, quite apart from major works in the UK. His non-railway work was also impressive: docks, factories and part of Bazalgette's colossal sewerage and embankment project in London that gave us, among more important things, the Victoria and Albert Embankments, new streets and to some extent the District and Circle Lines. By 1870 he had built one mile in every twenty across the world, and in every inhabited continent. When he died at the (Royal) Victoria Hotel at St Leonards on 8 December 1870 Brassey left close to £3,200,000, a quite enormous sum that in today's terms would probably have been over a thousand million. He had been through some serious scares when his contracts had not yielded what he had expected, and in the bank crisis of 1866, but he had survived Thomas Brassey, contractor (or probably it his son Thomas) to build the colossal country house of Normanhurst Court in the parish of Catsfield. -

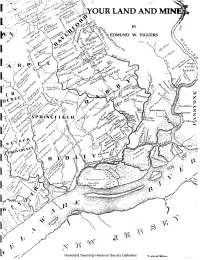

YOUR LAND and .,1" �,Nil.„,,9 : �1; �V.11" I, ,, 'Ow ,, �.� 01,� �; by F•W•R-I-Ti`I'''� --:-— , --I-„‘," ."; ,,, R \, • •

, .„,, „,,,.-1 Ie. • r•11.,; s v_ .:11;.--''' . %. ....:. _,11,101, ol'I - -, 1,' o‘ v. - w •-• /...1a. ,'' ,,,- cy,of 10.0 \1,,IV _, , .01 ,;„,---- ', A 0, 016 „YOUR LAND AND .,1" ,Nil.„,,9 : 1; V.11" I, ,, 'ow ,, . 01, ; BY f•w•r-i-ti`I''' --:-— , --i-„‘," ."; ,,, r \, • • . O" ;._ . • N - .„t• .10 EDMUND W. VIGUERS 1 k , Iv' . • o': jrar.'!:, ..\ . , ...---1,4 s.., •-, 11"‘‘ 0 re 't' -----.V . ov1 .00 - II''',05‘ 410,1N ' --$A 01' 0' :•-..-•-• 1,,, lc -. ..00', 1 1 01 ,t,s1' . .01. ' . 113, ....-- 7-7. no". VI' • k‘"' .% ,00- IP' \i'l,ili, ,..., 1,'"° A1 "45 -,..., • N'' Ilt' ' 1 S' is 00,?' ill i 1, ,. R P• s.----,.. ,• , .10!..i01 , coil it 04,1 ' A ' .i ,N ‘ $v" ,. .‘i`‘ \\‘‘ 7,,.....111S \\ ‘i •• 71--. •--N.--.... •S'" fr. 101' • V . NNO . ft -• Iii‘...r1:;::::::11 ..., \''' • ' . 571:1:1)- . ''._;'' . •• A :::::::e 00c's:` ,,i i sCs•l‘ •`• ; ,,,Ai‘ •/ / ‘%5' S , Is i\ S' Y' , 6,•,,,y,,,.ib,,,, - /7 ()ME 111,7%W1: \\ 0" (..' \• 1' e...":;...... MM. : t " , ,,, , , , !....... \ ‘ s- ,..1. %.,.- '40) ‘‘‘s i - .1\''' '.:.. 01, 4.-. 1 • •••• C L" V (vi "':- ‘,5..‹.' • ' .‘AV *: ,v , 6s"-1.);',:.;'.,•-•>•' .:F:''..b;,„. I ,10 .i ,‘,, 4\ xt• .!, .0,. •,,,,,,,/7,,, , rrz •• ivo 1.,:i. te 7.1+10,-Pumbn DEN, ' NI,I. '\‘` \ ci • , \ lk9 o'' „,..,...,.. • ,,,,,A ,No , i ,r• ----. 110 0 . • •• 00 c„,-i.. r vS• , , ,,v s r. .,..va lCt° ::1//dr4,11;44nron ; . ,;kf c1 +IV eirsimint ‘\ \ ‘ •AO " e „, Ont 50. .0. .... .--, --: ,t‘" V, e VP R) l'N \G II k-:., L ss,.. 0 ' ---::- _ V01.--.,01'\,‘" vO „„ ,-. 7, • . -

History of Upland, PA

Chronology of Upland, PA from 1681 through 1939 and A Chronology of the Chester Mills from 1681 through 1858. Land in the area of today’s Upland was entirely taken up in the 1600’s by Swedes, and laid out in “plantations”. Swedes and Finns had settled on the west bank of the Delaware River as early as 1650. The Swedes called this area “Upland”. Peter Stuyvesant, Dutch Governor of New Amsterdam (now New York), forced the Swedes to capitulate and named the area “Oplandt”. September, 1664 – English Colonel Nichols captured New Amsterdam, it became “his majesty’s town of New York”. The Swedes decided it was “Upland” again. Local Indians were of the Lenni Lenape tribe – The Turtle Clan. An old Indian trail ran from Darby along the general route of the present MacDade Blvd. into the Chester area, where it followed today’s 24th Street to the present Upland Avenue. Here it turned down the hill passing the current Kerlin Street, and on to the area that is now Front Street where it turned right, following close to Chester Creek across the land which later would become Caleb Pusey’s plantation, and then made a crossing to the higher land on the opposite side of the creek. Dr. Paul Wallace, the Indian expert, sites this Indian trail; “The Indians could here cross over on stones and keep their moccasins dry”. The Indian name for the Chester Creek was “Meechaoppenachklan”, which meant. Large potato stream, or the stream along which large potatoes grow. From 1681 . William Penn, being a man who learned from the experiences of others, was intent on providing a vital infrastructure for the settler/land owners in the new colony. -

Historic Resources Documentation & Context

Appendix B Historic Resources Documentation & Context This Appendix provides detailed property information for historic resources discussed in Chapter 4. This research was completed via extensive deed research undertaken by Chester County Archives. Numbers listed before the historic resource property owner names refer to ‘Map IDs’ in Chapter 4 tables and maps. The present-day municipal name is noted in parentheses after the resource property owner name. The term ‘site’ indicates the structure is no longer extant. If the 1777 property owner claimed property damages1 related to the battle, Plunder, Depredation and/or Suffering is indicated. This Appendix also provides a brief historic context of each municipality discussed in Chapter 4. The 1777 property and road maps were developed by Chester County Archives based upon property lines in 1883 Breou’s Maps, deed research, and original road papers. Associated Encampment & Approach Landscapes Historic Resources Robert Morris/Peter Bell Tavern Site/Unicorn Tavern Site (Robert Morris – Plunder & Peter Bell - Depredation - Kennett Square) 03.02: 108 N. Union Street (Parcel #3-2-204) Robert Morris of Philadelphia (the financier of the American Revolution) purchased an 87 acre tract of land in March of 1777 of which this lot was a part (Deed Book W pg 194). He sold it in 1779 to Peter Bell, an inn holder, who had been operating the tavern since 1774. Located on the northwest corner of State and Union Streets, the tavern had been rebuilt in 1777 from black stone on the site of the earlier tavern which had burned. Knyphausen had his headquarters here. There is evidence that his property was plundered. -

![TV/Series, 9 | 2016, « Guerres En Séries (I) » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 18 Mai 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1578/tv-series-9-2016-%C2%AB-guerres-en-s%C3%A9ries-i-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-mars-2016-consult%C3%A9-le-18-mai-2021-381578.webp)

TV/Series, 9 | 2016, « Guerres En Séries (I) » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 18 Mai 2021

TV/Series 9 | 2016 Guerres en séries (I) Séries et guerre contre la terreur TV series and war on terror Marjolaine Boutet (dir.) Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/617 DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.617 ISSN : 2266-0909 Éditeur GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Référence électronique Marjolaine Boutet (dir.), TV/Series, 9 | 2016, « Guerres en séries (I) » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 mars 2016, consulté le 18 mai 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/617 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/tvseries.617 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 18 mai 2021. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 1 Ce numéro explore de façon transdisciplinaire comment les séries américaines ont représenté les multiples aspects de la lutte contre le terrorisme et ses conséquences militaires, politiques, morales et sociales depuis le 11 septembre 2001. TV/Series, 9 | 2016 2 SOMMAIRE Préface. Les séries télévisées américaines et la guerre contre la terreur Marjolaine Boutet Détours visuels et narratifs Conflits, filtres et stratégies d’évitement : la représentation du 11 septembre et de ses conséquences dans deux séries d’Aaron Sorkin, The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) et The Newsroom (HBO, 2012-2014) Vanessa Loubet-Poëtte « Tu n’as rien vu [en Irak] » : Logistique de l’aperception dans Generation Kill Sébastien Lefait Between Unsanitized Depiction and ‘Sensory Overload’: The Deliberate Ambiguities of Generation Kill (HBO, 2008) Monica Michlin Les maux de la guerre à travers les mots du pilote Alex dans la série In Treatment (HBO, 2008-2010) Sarah Hatchuel 24 heures chrono et Homeland : séries emblématiques et ambigües 24 heures chrono : enfermement spatio-temporel, nœud d’intrigues, piège idéologique ? Monica Michlin Contre le split-screen. -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

Hunter's Hand Book of Victoria Bridge, Illustrated with Wood-Cuts. a Brief

^ta. l^v-t dqe Cthtmt'a Uttmerattj SJtbrarg . ^<VU^ BL,SH l &!iv,IX.Jl(NTER^ p'CKup . GRAND TRUNK VICTORIA BRIDGE CELEBRATIOI NOW READY EOMTEI ft.PiiC WITH two LirnoGBAPHic views, In Three Tints, (Summer and Winter). Size of each Plate x 8 inches, executed in the best style of the Art, by Saroj Major & Knapp, of New York. The work is dedicated, by permission, to the Grand Tr Railway Company of Canada. HUNTER & PICKUP having purchased the Electrotypes Plates, together with the Copyright of " Hunter's Panora Guide from Niagara to Quebec," of J. P. Jewett & Co., Bos former Proprietors and Publishers, have made arrangem* with Mr. J. Lovell, Printer and Publisher, Montreal, and now prepared to receive orders, wholesale and retail. On the receipt of one dollar, post paid, the two View Victoria Bridge, with Hand Book, will be sent, free of post to any. part of Canada. For $1, 25cts. the Hand-Book Views will be sent to England, Ireland or Scotland, neatly cured in wrappers. The two Views without the Hand-Boot $1, free of any other charge. To be had at the Book Stores in Town and Country ; i News-boys on board the Cars, and at rad&B&zg »w &m ADJOINING Post Office, Montreal. Orders from Great Britain, United States, and the Bri Provinces, to the undersigned, post paid, will receive mimed attention. HUNTER <Sr PICKUji Montreal, July, 1860. HUNTEE'S HAND BOOK OF l .„ THE VICTORIA BRIDGE. — ENTRANCE TO THE VICTORIA BRIDGE. The inscription on the lintel over the entrance to the abu t. -

Putting Historic Preservation Into Practice: the Friends of the Caleb Pusey House, Inc

PUTTING HISTORIC PRESERVATION INTO PRACTICE: THE FRIENDS OF THE CALEB PUSEY HOUSE, INC. AND THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY RESTORATION OF A SEVENTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA HOME. By Melissa Elaine Engimann A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2006 Copyright 2006 Melissa E. Engimann All Rights Reserved UMI Number: 1435841 UMI Microform 1435841 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 PUTTING HISTORIC PRESERVATION INTO PRACTICE: THE FRIENDS OF THE CALEB PUSEY HOUSE, INC. AND THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY RESTORATION OF A SEVENTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA HOME. by Melissa Elaine Engimann Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Pauline Eversmann, M.Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ___________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in Early American Material Culture Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Thomas M. Apple, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Conrado M. Gempesaw II, Ph.D. Vice-Provost for Academic and International Programs ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In researching and writing this thesis, I am indebted to a number of very generous people. My first thank you is to Jana Maxwell, archivist at the Caleb Pusey House in Upland, Pennsylvania, and the members of the Friends of the Caleb Pusey House, Inc. Mrs. Maxwell and the Friends of the Caleb Pusey House kindly provided me with the use of their time and resources, as well as unfettered access to the Caleb Pusey House archives. -

The Simonton Literary Prize on Robert Hope-Jones. Awarded to D. Hyde at the 2007 A.T.O.S

The Simonton Literary Prize was established in honour if Richard Simonton who was a founder of the American Theater Organ Enthusiasts, which eventually became known as the American Theatre Organ Society (A.T.O.S.) The purpose of the prize is to encourage and reward original research and writing in the area of theatre organ history, restoration and conversation. The work of Don Hyde, chairman of the Lancastrian Theatre Organ Trust, on the new research into Hope-Jones and the people he has made contact with has entered new grounds in the history associated with theatre organs This, plus a little bit of arm twisting resulted in Don writing this paper which was submitted for the Simonton prize in 2007. The prize was awarded to Don Hyde at the American Theatre Organ Society Convention in New York in 2007. The purpose of this paper is to record the recent research that has been carried out into the world of Robert Hope-Jones and the people who lived and worked in his environment and whom he met during the course of some of the work he did during his organ manufacturing time in Great Britain before he emigrated to the United States. The Lancastrian Theatre Organ Trust has been troubled for some time that almost all of the original pipe organs built in Britain by Hope- Jones have been totally rebuilt, dramatically modified over the years by various organ builders, or have been scrapped. Since its foundation in 1968 the Lancastrian Theatre Organ Trust has been acutely aware of its close proximity to the birthplace of Robert Hope-Jones and to the area at Birkenhead on the Wirral in Cheshire where he started his ground breaking work on pipe organs. -

Chapter 3: Historic Resources Plan

Chapter 3 Historic Resources Plan The Brandywine Battlefield covers 35,000 acres, of which 14,000 acres have remained undeveloped since 1777. As a result, there are abundant historic resources within the Battlefield which has been designated as a “Protected Areas of National Significance” in Landscapes2, the Chester County Comprehensive Policy Plan. The 2010 ABPP Battle of Brandywine: Historic Resource Survey and Animated Map (2010 ABPP Survey) identified numerous historic resources that are further evaluated in this chapter, along with newly identified resources. This chapter also discusses the Brandywine Battlefield National Landmark (the Landmark) which, until now, was never mapped using modern cartographical methods. This chapter also discusses “Battlefield Planning Boundaries” which are mapped resource areas used in municipal land use ordinances. Lastly, this chapter identifies historic sites which could be protected as open space, and then addresses municipal ordinances that address historic resources preservation. This chapter also includes a Historic Resources Plan for the Battlefield. This plan was developed based on an evaluation that prioritizes those parts of the Battlefield that are well suited to be studied in greater detail or protected. The Battlefield is large and includes extensive areas of developed land in which there are no existing historic structures. Even the topography of the land has been graded in many areas so that hills or swales that were present in 1777 no longer exist. To determine what areas warrant further study and protection, an analysis was conducted that focuses on historic resources such as buildings; land areas that were used by troops for camping, marching, or combat; and defining features such as villages or streams that were important to the events of the Battle.