Chapter 3: Historic Resources Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

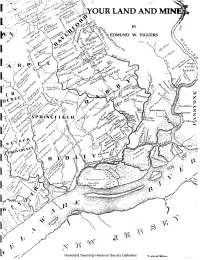

YOUR LAND and .,1" �,Nil.„,,9 : �1; �V.11" I, ,, 'Ow ,, �.� 01,� �; by F•W•R-I-Ti`I'''� --:-— , --I-„‘," ."; ,,, R \, • •

, .„,, „,,,.-1 Ie. • r•11.,; s v_ .:11;.--''' . %. ....:. _,11,101, ol'I - -, 1,' o‘ v. - w •-• /...1a. ,'' ,,,- cy,of 10.0 \1,,IV _, , .01 ,;„,---- ', A 0, 016 „YOUR LAND AND .,1" ,Nil.„,,9 : 1; V.11" I, ,, 'ow ,, . 01, ; BY f•w•r-i-ti`I''' --:-— , --i-„‘," ."; ,,, r \, • • . O" ;._ . • N - .„t• .10 EDMUND W. VIGUERS 1 k , Iv' . • o': jrar.'!:, ..\ . , ...---1,4 s.., •-, 11"‘‘ 0 re 't' -----.V . ov1 .00 - II''',05‘ 410,1N ' --$A 01' 0' :•-..-•-• 1,,, lc -. ..00', 1 1 01 ,t,s1' . .01. ' . 113, ....-- 7-7. no". VI' • k‘"' .% ,00- IP' \i'l,ili, ,..., 1,'"° A1 "45 -,..., • N'' Ilt' ' 1 S' is 00,?' ill i 1, ,. R P• s.----,.. ,• , .10!..i01 , coil it 04,1 ' A ' .i ,N ‘ $v" ,. .‘i`‘ \\‘‘ 7,,.....111S \\ ‘i •• 71--. •--N.--.... •S'" fr. 101' • V . NNO . ft -• Iii‘...r1:;::::::11 ..., \''' • ' . 571:1:1)- . ''._;'' . •• A :::::::e 00c's:` ,,i i sCs•l‘ •`• ; ,,,Ai‘ •/ / ‘%5' S , Is i\ S' Y' , 6,•,,,y,,,.ib,,,, - /7 ()ME 111,7%W1: \\ 0" (..' \• 1' e...":;...... MM. : t " , ,,, , , , !....... \ ‘ s- ,..1. %.,.- '40) ‘‘‘s i - .1\''' '.:.. 01, 4.-. 1 • •••• C L" V (vi "':- ‘,5..‹.' • ' .‘AV *: ,v , 6s"-1.);',:.;'.,•-•>•' .:F:''..b;,„. I ,10 .i ,‘,, 4\ xt• .!, .0,. •,,,,,,,/7,,, , rrz •• ivo 1.,:i. te 7.1+10,-Pumbn DEN, ' NI,I. '\‘` \ ci • , \ lk9 o'' „,..,...,.. • ,,,,,A ,No , i ,r• ----. 110 0 . • •• 00 c„,-i.. r vS• , , ,,v s r. .,..va lCt° ::1//dr4,11;44nron ; . ,;kf c1 +IV eirsimint ‘\ \ ‘ •AO " e „, Ont 50. .0. .... .--, --: ,t‘" V, e VP R) l'N \G II k-:., L ss,.. 0 ' ---::- _ V01.--.,01'\,‘" vO „„ ,-. 7, • . -

History of Upland, PA

Chronology of Upland, PA from 1681 through 1939 and A Chronology of the Chester Mills from 1681 through 1858. Land in the area of today’s Upland was entirely taken up in the 1600’s by Swedes, and laid out in “plantations”. Swedes and Finns had settled on the west bank of the Delaware River as early as 1650. The Swedes called this area “Upland”. Peter Stuyvesant, Dutch Governor of New Amsterdam (now New York), forced the Swedes to capitulate and named the area “Oplandt”. September, 1664 – English Colonel Nichols captured New Amsterdam, it became “his majesty’s town of New York”. The Swedes decided it was “Upland” again. Local Indians were of the Lenni Lenape tribe – The Turtle Clan. An old Indian trail ran from Darby along the general route of the present MacDade Blvd. into the Chester area, where it followed today’s 24th Street to the present Upland Avenue. Here it turned down the hill passing the current Kerlin Street, and on to the area that is now Front Street where it turned right, following close to Chester Creek across the land which later would become Caleb Pusey’s plantation, and then made a crossing to the higher land on the opposite side of the creek. Dr. Paul Wallace, the Indian expert, sites this Indian trail; “The Indians could here cross over on stones and keep their moccasins dry”. The Indian name for the Chester Creek was “Meechaoppenachklan”, which meant. Large potato stream, or the stream along which large potatoes grow. From 1681 . William Penn, being a man who learned from the experiences of others, was intent on providing a vital infrastructure for the settler/land owners in the new colony. -

Historic Resources Documentation & Context

Appendix B Historic Resources Documentation & Context This Appendix provides detailed property information for historic resources discussed in Chapter 4. This research was completed via extensive deed research undertaken by Chester County Archives. Numbers listed before the historic resource property owner names refer to ‘Map IDs’ in Chapter 4 tables and maps. The present-day municipal name is noted in parentheses after the resource property owner name. The term ‘site’ indicates the structure is no longer extant. If the 1777 property owner claimed property damages1 related to the battle, Plunder, Depredation and/or Suffering is indicated. This Appendix also provides a brief historic context of each municipality discussed in Chapter 4. The 1777 property and road maps were developed by Chester County Archives based upon property lines in 1883 Breou’s Maps, deed research, and original road papers. Associated Encampment & Approach Landscapes Historic Resources Robert Morris/Peter Bell Tavern Site/Unicorn Tavern Site (Robert Morris – Plunder & Peter Bell - Depredation - Kennett Square) 03.02: 108 N. Union Street (Parcel #3-2-204) Robert Morris of Philadelphia (the financier of the American Revolution) purchased an 87 acre tract of land in March of 1777 of which this lot was a part (Deed Book W pg 194). He sold it in 1779 to Peter Bell, an inn holder, who had been operating the tavern since 1774. Located on the northwest corner of State and Union Streets, the tavern had been rebuilt in 1777 from black stone on the site of the earlier tavern which had burned. Knyphausen had his headquarters here. There is evidence that his property was plundered. -

2016 Annual Report of the Maryland Historical Trust July 1, 2015 - June 30, 2016 Maryland Department of Planning

2016 Annual Report of the Maryland Historical Trust July 1, 2015 - June 30, 2016 Maryland Department of Planning Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Department of Planning 100 Community Place Crownsville, MD 21032-2023 410-697-9591 www.planning.maryland.gov www.MHT.maryland.gov Table of Contents The Maryland Historical Trust Board of Trustees 2 Who We Are and How We Work 3 Maryland Heritage Structure Rehabilitation Tax Credit 5 Maryland Heritage Areas Program 9 African American Heritage Preservation Program 15 Architectural Research and Survey 16 Terrestrial Archeological Research and Survey 18 Maritime Archeological Research and Survey 20 Preservation Planning 22 Cultural Resources Hazard Mitigation Planning Program 24 Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum 26 Historic Preservation Easements 28 State and Federal Project Review 33 Military Monuments and Roadside Historical Markers 34 Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory 36 Public Archeology Programs 38 Cultural Resource Information Program 41 Maryland Preservation Awards 42 The Maryland Historical Trust Board of Trustees The Maryland Historical Trust is governed by a 15-member Board of Trustees, including the Governor, the Senate President and the House Speaker or their designees, and 12 members appointed by the Governor. At least two trustees must be qualified with an advanced degree in archeology or a closely related field and shall have experience in the field of archeology. Of the trustees qualified in the field of archeology, at least one must have experience in the field of submerged archeology and at least one must have experience in the field of terrestrial archeology. The term of a member is 4 years. Trustees Appointed by the Governor: Albert L. -

Dates Associated with the 250Th Anniversary of the American Revolution in Maryland January 14, 2019 Year Date(S) Event Location

Dates Associated with the 250th Anniversary of the American Revolution in Maryland January 14, 2019 Year Date(s) Event Location 1765 March 22 Passage of Stamp Act. A related site is Patuxent Manor, the home of Calvert County political leader Charles Grahame, a vocal critic of the Act (Owings) 1765 September 2 Tax collector hung in effigy (Elkridge) Howard County 1765 August 26 Attack on tax collector Annapolis 1765 November 23 Repudiation Day; Frederick County judges “repudiate” the Stamp Act Frederick 1772 March 28 Cornerstone laid for Maryland State House, the oldest state capitol in Annapolis continuous legislative use in the Unites States 1774 Establishment of Catoctin Iron Furnace at Bloomsbury, supplier of Frederick County shot and ammunition to Colonial forces (Urbana) 1774 May 23 Chestertown Tea Party (“according to tradition”) and Chestertown Kent County Resolves 1774 May 24 Talbot Resolves protest the closing of the Port of Boston and pledge Talbot County support “as friends to liberty” (Easton) 1774 June 11 Hungerford Resolves adopted in support of the Sons of Liberty Montgomery County (Rockville) 1774 October 19 Burning of the Peggy Stewart/Annapolis Tea Party Annapolis Year Date(s) Event Location 1775 March 22 Bush Declaration adopted by the Committee of Harford, expressing Harford County support for the Patriot cause 1776 July 17-29 British Landing repulsed at St. George Island St. Mary’s County 1776 August 27 Maryland troops earn the honor as the “Maryland 400” for their heroic sacrifice in covering the retreat of Washington’s Army at the Battle of Brooklyn (Battle of Long Island) 1776 October 1 Montgomery and Washington Counties are established by the Maryland Montgomery and Frederick Constitutional Convention by dividing the eastern and western portions Counties of Frederick County. -

Putting Historic Preservation Into Practice: the Friends of the Caleb Pusey House, Inc

PUTTING HISTORIC PRESERVATION INTO PRACTICE: THE FRIENDS OF THE CALEB PUSEY HOUSE, INC. AND THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY RESTORATION OF A SEVENTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA HOME. By Melissa Elaine Engimann A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2006 Copyright 2006 Melissa E. Engimann All Rights Reserved UMI Number: 1435841 UMI Microform 1435841 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 PUTTING HISTORIC PRESERVATION INTO PRACTICE: THE FRIENDS OF THE CALEB PUSEY HOUSE, INC. AND THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY RESTORATION OF A SEVENTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA HOME. by Melissa Elaine Engimann Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Pauline Eversmann, M.Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ___________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in Early American Material Culture Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Thomas M. Apple, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Conrado M. Gempesaw II, Ph.D. Vice-Provost for Academic and International Programs ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In researching and writing this thesis, I am indebted to a number of very generous people. My first thank you is to Jana Maxwell, archivist at the Caleb Pusey House in Upland, Pennsylvania, and the members of the Friends of the Caleb Pusey House, Inc. Mrs. Maxwell and the Friends of the Caleb Pusey House kindly provided me with the use of their time and resources, as well as unfettered access to the Caleb Pusey House archives. -

Chapter 7: Upland County Park Chapter 7: Upland County Park

Upland County Park 7 Volume III: County Parks and Recreation Plan Chapter 7: Upland County Park Chapter 7: Upland County Park INTRODUCTION BRIEF HISTORY The earliest relevant history of the Upland County Park area was the construction of Caleb Pusey’s house in 1638 and various mills and a race hydraulically powered by Chester Creek. The Mills created by Pusey were successful through the 1700’s even after Pusey sold them in 1709. Further development of the mills in the 1800’s, the Pusey site, on land in Upland Park and in the Upland area was directly attributed to the Crozer Family. John Price Crozer bought the mills and the Pusey tract in 1845. The Crozers’ further developed the Upland Park area to include small frame houses and a school house. John Crozer eventually turned the mills into a very profitable cotton factory with steam power. From his prospering enterprises and the ever-growing workforce associated, Crozer was able to develop the area into a village of houses and mansions, most of which have not survived to this today. One of the mansions, the George K. Crozer mansion (affectionately known as the “Netherleigh” mansion), was built in 1869 on nearly 38 acres. The Mansion included a carriage house, a springhouse, a coachman’s house, outbuildings and a barn. Today only the carriage house and the remnants of the driveway access remain as a historical relic from this time. When George K. Crozer died, the Netherleigh mansion what purchased by Dr. Israel Bram as a private sanatorium until Bram sold the 38 acre Figure 7-1: Rendering of the Netherleigh Mansion property to the Salvation Army in 1945. -

Municipal C Omprehensive Plan

B ROOKHAVEN, P ARKSIDE, AND UPLAND M ULTI- MUNICIPAL C OMPREHENSIVE PLAN DELAWARE COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT COMPREHENSIVE PLAN FOR THE BOROUGHS OF BROOKHAVEN, PARKSIDE, AND UPLAND August 2009 Prepared for the citizens of the Boroughs of Brookhaven, Parkside, and Upland by the Delaware County Planning Department This project was funded in part by a grant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Community and Economic Development, under the Land Use Planning and Technical Assistance Program (LUPTAP), and with funding from the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program under Title I of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, P.L. 93-383, as amended. Printed on Recycled Paper BROOKHAVEN BOROUGH Council and Mayor Borough Officials Planning Commission Michael S. Hess, Mayor Mary McKinley, George Letherbury, John J. Wilwert, Jr., Secretary/Manager Chair President William P. Lincke, Solicitor Margaret Eighan, Vawn Donaway, Vice F. Clark Walton, Engineer Vice Chair President Harold Hampton, Zoning Officer Ronald Jackson Harry L. Seth Jon Grant, Code Enforcement Stan Warfield Donna Erickson Officer Ronald Kerins, Jr. Daniel McCray Harry Feindt, Building Inspector Michael A. Ruggieri, Jr. Janice Sawicki PARKSIDE BOROUGH Council and Mayor Borough Officials Planning Commission Ardele Gordon, Mayor Linda Higgins, Secretary Shirley Purcival Shirley Purcival, President Joe Possenti, Jr., Treasurer Frank McCollum, Vice John J. Wills, Solicitor President Charles Catania, Engineer James Kilgallen Dave Favinger, Code Jacqueline File-Barlow Enforcement Officer Henry Ewing Joseph Ferguson, Building William Howell Inspector Jason Stamis UPLAND BOROUGH Council and Mayor Borough Officials Planning Commission Michael Ciach, Mayor Shirley Purcival, Manager Edward Mitchell Edward Mitchell, President Virginia Sentry, Secretary Dana Dudek Christine Peterson, Vice Robert E. -

Western Maryland Room Vertical File Collection Catalog

Western Maryland Room Vertical File Collection Page 1 Inventoried in 1999, and updated May 2009, by Marsha L. Fuller,CG. Updated July 2013 by Klara Shives, Graduate Intern. Catalog: File Name Description Date Orig Cross Reference AAUW Allegany Co., MD Growing Up Near Oldtown 2000 Deffinbaugh Memoirs Allegany Co., MD The War for The British Empire in Allegany County 1969 x Allegany Co., MD Pioneer Settlers of Flintstone 1986 Allegany Co., MD Ancestral History of Thomas F. Myers 1965 x Allegany Co., MD Sesquicentennial - Frostburg, MD 1962 x Allegany Co., MD Harmony Castle No.3 - Knights of the Mystic Chains 1894 x Midland, MD Allegany Co., MD (Box) Ashmon Sorrell's Tombstone 2007 Civil War Allegany Co., MD (Box) The Heart of Western Maryland Allegany Co., MD (Box) Kelly-Springfield Tire Co. 1962 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Ku Klux Klan 2008 Albert Feldstein Allegany Co., MD (Box) LaVale Toll House Allegany Co., MD (Box) List of Settlers in Allegany County 1787 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Mills, Grist and Flour Allegany Co., MD (Box) Miscellaneous clippings 1910-1932 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Names of towns, origin Allegany Co., MD (Box) National Highway - colored print Allegany Co., MD (Box) Old Allegany - A Century and A Half into the Past 1889 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Old Pictures of Allegany Co. 1981 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Ordeal in Twiggs Cave 1975 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Photographs of Western Maryland 1860-1925 1860-1925 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Piedmont Coal and Iron Company, Barton, MD (6) 1870s x Allegany Co., MD (Box) Pioneer log cabin Allegany -

Preservation in Ridley Creek State Park: Documentation of the Historic Farmsteads

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1993 Preservation in Ridley Creek State Park: Documentation of the Historic Farmsteads Jeffrey Robert Barr University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Barr, Jeffrey Robert, "Preservation in Ridley Creek State Park: Documentation of the Historic Farmsteads" (1993). Theses (Historic Preservation). 333. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/333 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Barr, Jeffrey Robert (1993). Preservation in Ridley Creek State Park: Documentation of the Historic Farmsteads. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/333 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Preservation in Ridley Creek State Park: Documentation of the Historic Farmsteads Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Barr, Jeffrey Robert (1993). Preservation in Ridley Creek State Park: Documentation of the Historic Farmsteads. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/333 UNivERsmry PENNSYL\^\NIA. LIBRARIES PRESERVATION IN RIDLEY CREEK STATE PARK: DOCUMENTATION OF THE HISTORIC FARMSTEADS by JEFFREY ROBERT BARR A Thesis in Historic Preservation Presented to the faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1993 .^(Vju*^ Milner, Adjunct Associate Professor of Architecture in HistJ)ric Preservation, Advisor r in Historic Preservation, Reader ^-id G. -

Hessian Barracks T ., I AND· OR HISTORIC: L Frederick Barracks

FHD-243 late 18th C. Frederick Barracks 242 South Market Street Frederick Public Following the general concept of military barracks in North America constructed during the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the Frederick Barracks is a handsome two story, L-shaped stone structure. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970, the barracks has adapted itself to a variety of public uses: a state armory, an agricultural exhibition hall, a temporary hos pital during the Civil War, and finally the first classrooms for the Maryland School for the Deaf. Presently, the building serves as the school's museum. I ~U'-i-J.L/ 3 Fer• 10·300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STA'tE! (Julr 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Maryland ~ ..------ COUNTY• NATIOtolA.L REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES , Frederick INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USf ONLY ENTRY NUMBElll I DATE (Type all cntrif's - complete applicable sections) I Il. 11. NAME l C OM>fON • . Hessian Barracks t ., I AND· OR HISTORIC: l Frederick Barracks. Revolutionarv Barracks I 12. LOCATION ' STREET ANC' NUM•IER: . 242 South Market Street -CITY OA TOWN: i Frederick STATE I CODE !COUNTY: I CODE .l Mar~land I 24 I Frederick In.,, t (3. CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNfRSHIP STATUS (CMC'I< On•) TO THE PUBLIC "'z [] District [X Building (lQ Public Public Acquialti-: fiCI Occupied Yea: 0 Restricted r 1 Site 0 Structure 0 Priwote 0 In Process D Unoccupied Kl Unrea tr i cted 0 Object 0 Both 0 Being Co.naidered 0 Proaer•otion work D l- In progress D No u P•IESENT USIE (C"hrdr One or AJore ns Appropriate) ..:. -

Curated Ground: Public History, Military Memory, and Shared Authority at Battle Sites in North America

CURATED GROUND: PUBLIC HISTORY, MILITARY MEMORY, AND SHARED AUTHORITY AT BATTLE SITES IN NORTH AMERICA A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS by Joseph T. Humnicky Diploma Date May 2020 Thesis Approvals: Dr. Seth Bruggeman, Thesis Advisor, History Dr. Hilary Iris Lowe, History ABSTRACT This thesis is a synthesis of two separate research projects conducted in the summer of 2018 and the spring of 2020. The first project was conducted in conjunction with the Fort Ticonderoga Association as a means of exploring the memory and legacy of a historic military landmark in written history, interpretation, and public memory. The second project was conducted in conjunction with the National Park Service (NPS) and the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Instead of focusing on a single site, this second study looked at a collection of federal, state, local, and private battlefields in order to catalog the administrative histories, the boundary expansions, and the preservation priorities that have occurred both at the individual sites as well as collectively over time. The scope of the NEH grant was meant to evaluate the role that the NPS, ABPP, and the Department of the Interior have played in developing and refining preservation standards used by federal and non-federal sites. This thesis integrates the two studies in order to examine the correlation between public memory and battle sites in North America. Images were created using Google Maps; Journey Through Hallowed Grounds images are i provided by the NPS website https://www.nps.gov/subjects/heritageareas/discover- nhas.htm TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………….................i ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………………….iii CHAPTER 1.