Preservation in Ridley Creek State Park: Documentation of the Historic Farmsteads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voting Opens for Conservancy's Architecture Hall of Fame

Links (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/links/) Archives (http://nl.newsbank.com/sites/chlp/) Classieds (/classieds2015/) Careers (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/careers/) Contact (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/contact/) About (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/about/) Subscribe (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/subscribe/) Advertising (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/advertising/) (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com) Welcome to Chestnut Hill (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/welcome-chestnut-hill/) (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Reign.Guide_Layout-1-8.pdf) Voting opens for Conservancy’s Architecture Hall of Fame Posted on October 31, 2019 (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/2019/10/31/voting-opens-for-conservancys- architecture-hall-of-fame/) by Contributor (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/author/contributor/) (https://www.chestnuthilllocal.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/WEB-Anglecot.jpg) Anglecot on 403 E. Evergreen Ave. (1883; Wilson Eyre, Architect) This shingle-style house was designed by noted architect Wilson Eyre Jr., and was heralded as innovative in form and plan and for its mix of materials. All of its additions between initial construction and 1910 were by Eyre, illustrating the evolution of his style. After use as a nursing home, Anglecot was converted into nine condominiums in 1982-83 in a project that restored the single- family style facade and conserved the surrounding open space. (Photo by Wendy Concannon) The Chestnut Hill Conservancy welcomes public voting through Nov. 22. Public voting is now open for the Chestnut Hill Conservancy’s Chestnut Hill Architectural Hall of Fame, a distinguished list of the neighborhood’s most treasured signicant buildings structures and landscapes, chosen by public vote. Vote online (http://chconservancy.org/advocacy/architectural-hall-of-fame-vote-2019) now or at the conservancy’s oce (8708 Germantown Ave.). -

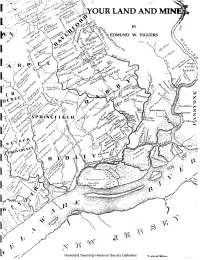

YOUR LAND and .,1" �,Nil.„,,9 : �1; �V.11" I, ,, 'Ow ,, �.� 01,� �; by F•W•R-I-Ti`I'''� --:-— , --I-„‘," ."; ,,, R \, • •

, .„,, „,,,.-1 Ie. • r•11.,; s v_ .:11;.--''' . %. ....:. _,11,101, ol'I - -, 1,' o‘ v. - w •-• /...1a. ,'' ,,,- cy,of 10.0 \1,,IV _, , .01 ,;„,---- ', A 0, 016 „YOUR LAND AND .,1" ,Nil.„,,9 : 1; V.11" I, ,, 'ow ,, . 01, ; BY f•w•r-i-ti`I''' --:-— , --i-„‘," ."; ,,, r \, • • . O" ;._ . • N - .„t• .10 EDMUND W. VIGUERS 1 k , Iv' . • o': jrar.'!:, ..\ . , ...---1,4 s.., •-, 11"‘‘ 0 re 't' -----.V . ov1 .00 - II''',05‘ 410,1N ' --$A 01' 0' :•-..-•-• 1,,, lc -. ..00', 1 1 01 ,t,s1' . .01. ' . 113, ....-- 7-7. no". VI' • k‘"' .% ,00- IP' \i'l,ili, ,..., 1,'"° A1 "45 -,..., • N'' Ilt' ' 1 S' is 00,?' ill i 1, ,. R P• s.----,.. ,• , .10!..i01 , coil it 04,1 ' A ' .i ,N ‘ $v" ,. .‘i`‘ \\‘‘ 7,,.....111S \\ ‘i •• 71--. •--N.--.... •S'" fr. 101' • V . NNO . ft -• Iii‘...r1:;::::::11 ..., \''' • ' . 571:1:1)- . ''._;'' . •• A :::::::e 00c's:` ,,i i sCs•l‘ •`• ; ,,,Ai‘ •/ / ‘%5' S , Is i\ S' Y' , 6,•,,,y,,,.ib,,,, - /7 ()ME 111,7%W1: \\ 0" (..' \• 1' e...":;...... MM. : t " , ,,, , , , !....... \ ‘ s- ,..1. %.,.- '40) ‘‘‘s i - .1\''' '.:.. 01, 4.-. 1 • •••• C L" V (vi "':- ‘,5..‹.' • ' .‘AV *: ,v , 6s"-1.);',:.;'.,•-•>•' .:F:''..b;,„. I ,10 .i ,‘,, 4\ xt• .!, .0,. •,,,,,,,/7,,, , rrz •• ivo 1.,:i. te 7.1+10,-Pumbn DEN, ' NI,I. '\‘` \ ci • , \ lk9 o'' „,..,...,.. • ,,,,,A ,No , i ,r• ----. 110 0 . • •• 00 c„,-i.. r vS• , , ,,v s r. .,..va lCt° ::1//dr4,11;44nron ; . ,;kf c1 +IV eirsimint ‘\ \ ‘ •AO " e „, Ont 50. .0. .... .--, --: ,t‘" V, e VP R) l'N \G II k-:., L ss,.. 0 ' ---::- _ V01.--.,01'\,‘" vO „„ ,-. 7, • . -

History of Upland, PA

Chronology of Upland, PA from 1681 through 1939 and A Chronology of the Chester Mills from 1681 through 1858. Land in the area of today’s Upland was entirely taken up in the 1600’s by Swedes, and laid out in “plantations”. Swedes and Finns had settled on the west bank of the Delaware River as early as 1650. The Swedes called this area “Upland”. Peter Stuyvesant, Dutch Governor of New Amsterdam (now New York), forced the Swedes to capitulate and named the area “Oplandt”. September, 1664 – English Colonel Nichols captured New Amsterdam, it became “his majesty’s town of New York”. The Swedes decided it was “Upland” again. Local Indians were of the Lenni Lenape tribe – The Turtle Clan. An old Indian trail ran from Darby along the general route of the present MacDade Blvd. into the Chester area, where it followed today’s 24th Street to the present Upland Avenue. Here it turned down the hill passing the current Kerlin Street, and on to the area that is now Front Street where it turned right, following close to Chester Creek across the land which later would become Caleb Pusey’s plantation, and then made a crossing to the higher land on the opposite side of the creek. Dr. Paul Wallace, the Indian expert, sites this Indian trail; “The Indians could here cross over on stones and keep their moccasins dry”. The Indian name for the Chester Creek was “Meechaoppenachklan”, which meant. Large potato stream, or the stream along which large potatoes grow. From 1681 . William Penn, being a man who learned from the experiences of others, was intent on providing a vital infrastructure for the settler/land owners in the new colony. -

Historic Resources Documentation & Context

Appendix B Historic Resources Documentation & Context This Appendix provides detailed property information for historic resources discussed in Chapter 4. This research was completed via extensive deed research undertaken by Chester County Archives. Numbers listed before the historic resource property owner names refer to ‘Map IDs’ in Chapter 4 tables and maps. The present-day municipal name is noted in parentheses after the resource property owner name. The term ‘site’ indicates the structure is no longer extant. If the 1777 property owner claimed property damages1 related to the battle, Plunder, Depredation and/or Suffering is indicated. This Appendix also provides a brief historic context of each municipality discussed in Chapter 4. The 1777 property and road maps were developed by Chester County Archives based upon property lines in 1883 Breou’s Maps, deed research, and original road papers. Associated Encampment & Approach Landscapes Historic Resources Robert Morris/Peter Bell Tavern Site/Unicorn Tavern Site (Robert Morris – Plunder & Peter Bell - Depredation - Kennett Square) 03.02: 108 N. Union Street (Parcel #3-2-204) Robert Morris of Philadelphia (the financier of the American Revolution) purchased an 87 acre tract of land in March of 1777 of which this lot was a part (Deed Book W pg 194). He sold it in 1779 to Peter Bell, an inn holder, who had been operating the tavern since 1774. Located on the northwest corner of State and Union Streets, the tavern had been rebuilt in 1777 from black stone on the site of the earlier tavern which had burned. Knyphausen had his headquarters here. There is evidence that his property was plundered. -

"Charles Lang Freer: an American

americanbungalow.com Summer 2018 AmericAn BungAlow Issue 96 summer 2018 THE CHARLES LANG FREER HOUSE. THE BLUESTONE WAS QUARRIED IN FREER’S HOMETOWN, KINGSTON, NEW YORK. THE HORSESHOE ARCH IS EMBEDDED IN WHAT WAS ORIGINALLY THE CARRIAGE HOUSE. IN 1904–6 WILSON EYRE, JR. REMODELED IT TO ACCOM- MODATE JAMES WHISTLER’S FAMOUS PEACOCK ROOM, AND AN ADDITIONAL TOP-LIGHTED ART GALLERY. RIGHT: THE FLIGHT OF STAIRS IS BROKEN AT A LANDING WITH AN ORIEL WINDOW. EYRE DIMINISHED THE VERTICAL THRUST OF THE STAIRS TO AVOID DISTURBING THE DOMINANT HORIZONTAL LINES. NOTE THE REAPPEARANCE OF THE HORSESHOE ARCH ON THE INTERIOR. THE LEAF- FORM LIGHTING FIXTURE, DESIGNED BY EYRE, AND MODELED BY EDWARD MAENE, IS VISIBLE AT TOP RIGHT. BY DOUGLAS J. FORSYTH Charles hen preservationists think of Detroit, their inclination is to mourn Lang for buildings lost over W the years. Certainly many fi ne structures have come down. From the early Freer An 1950s, the city suffered a radical loss of population. Fortunately, residents now show signs of returning. So we have reason to celebrate this renewal American by calling attention to the astonish- ing inventory of fi ne buildings that remain. One striking example is the shin- Success gle-style dwelling that Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) had built, begin- ning in 1890, on E. Ferry Ave. (now Story E. Ferry St.). His architect was Wil- son Eyre, Jr. (1858–1944), a master of the shingle style of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Thanks to the work of the late Vincent Scully, THE MAIN HALL. -

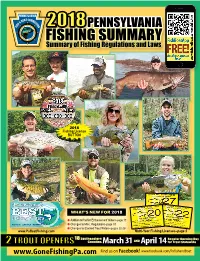

2018 Pennsylvania Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws PERMITS, MULTI-YEAR LICENSES, BUTTONS

2018PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws 2018 Fishing License BUTTON WHAT’s NeW FOR 2018 l Addition to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 l Changes to Misc. Regulations–page 16 l Changes to Stocked Trout Waters–pages 22-29 www.PaBestFishing.com Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 31 AND April 14 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the LOCATION PFBC S/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. THANK YOU FOR MORE INFORMATION: for the purchase STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: license! Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish and Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: Commonwealth’s aquatic resources EDUCATION COURSES FOLLOW US: www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. REGION OFFICES: LAW ENFORCEMENT/EDUCATION Contents Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating opportunities. Contact Education for information about fishing and boating programs and boating safety education. -

Putting Historic Preservation Into Practice: the Friends of the Caleb Pusey House, Inc

PUTTING HISTORIC PRESERVATION INTO PRACTICE: THE FRIENDS OF THE CALEB PUSEY HOUSE, INC. AND THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY RESTORATION OF A SEVENTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA HOME. By Melissa Elaine Engimann A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2006 Copyright 2006 Melissa E. Engimann All Rights Reserved UMI Number: 1435841 UMI Microform 1435841 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 PUTTING HISTORIC PRESERVATION INTO PRACTICE: THE FRIENDS OF THE CALEB PUSEY HOUSE, INC. AND THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY RESTORATION OF A SEVENTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA HOME. by Melissa Elaine Engimann Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Pauline Eversmann, M.Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ___________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in Early American Material Culture Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Thomas M. Apple, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Conrado M. Gempesaw II, Ph.D. Vice-Provost for Academic and International Programs ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In researching and writing this thesis, I am indebted to a number of very generous people. My first thank you is to Jana Maxwell, archivist at the Caleb Pusey House in Upland, Pennsylvania, and the members of the Friends of the Caleb Pusey House, Inc. Mrs. Maxwell and the Friends of the Caleb Pusey House kindly provided me with the use of their time and resources, as well as unfettered access to the Caleb Pusey House archives. -

Pub 316 Bike 2/4 Revision

Philadelphia and the Countryside PennDOT District Bicycling/Pedestrian Coordinators Steve Dunlop - District 6 Steve Pohowsky - District 5 Bucks, Montgomery, Chester, Northampton, Berks and Lehigh Counties Philadelphia, and Delaware Counties 1002 Hamilton Street 7000 Geerdes Boulevard Allentown, 18101 King of Prussia, 19406 (610) 871-4490 (610) 205-6996 [email protected] Bicycle Advocacy Organizations Southeastern Pennsylvania Bicycle The Coalition for Appropriate Issues Task Force Transportation (CAT) 190 North Independence Mall West Lehigh Valley Bike/Ped Transit Center Philadelphia, 19106 60 W. Broad Street Contact: John Madera Bethlehem, 18018 (215) 238-2854 Contact: Steve Schmitt (610) 954-5744 The Bicycle Coalition of Greater [email protected] Philadelphia (BCGP) 252 S. 11th Street Philadephia, 19107 Contact: John Boyle (215) BICYCLE Planning Organizations Delaware Valley Regional Berks County Planning Commission Planning Commission Berks County Services Center 190 North Independence Mall West 633 Court Street, 14th Flr 8th Floor Reading, 19601 Philadelphia, 19106 (610) 478-6300 Contact: John Madera Contact: Michael Golembiewski (215) 238-2854 [email protected] [email protected] www.co.berks.pa.us/planning Lehigh Valley Planning Commission 961 Marcon Boulevard, Suite 310 Allentown, 18109 (610) 264-4544 Contact: Joe Gurinko [email protected] Philadelphia and the Countryside 28 Tourism Promotion Agencies/Convention and Visitors Bureaus Bucks County Conference Lebanon Valley Exposition Corporation and Visitors Bureau, Inc 80 Rocherty Road 3207 Street Road, Bensalem, 19020 Lebanon, PA 17042 (800) 836-2825 (717) 273-3670 www.buckscountycvb.org www.visitlebanoncounty.com Brandywine Conference Lehigh Valley Convention and Visitors Bureau and Visitor’s Bureau One Beaver Valley Road, Chadds Ford, 19317 840 Hamilton Street, Suite 200 (800) 343-3983 Allentown, 18101 www.brandywinecvb.org (800) 747-0561 www.lehighvalleypa.org Chester Co. -

Chapter 3: Historic Resources Plan

Chapter 3 Historic Resources Plan The Brandywine Battlefield covers 35,000 acres, of which 14,000 acres have remained undeveloped since 1777. As a result, there are abundant historic resources within the Battlefield which has been designated as a “Protected Areas of National Significance” in Landscapes2, the Chester County Comprehensive Policy Plan. The 2010 ABPP Battle of Brandywine: Historic Resource Survey and Animated Map (2010 ABPP Survey) identified numerous historic resources that are further evaluated in this chapter, along with newly identified resources. This chapter also discusses the Brandywine Battlefield National Landmark (the Landmark) which, until now, was never mapped using modern cartographical methods. This chapter also discusses “Battlefield Planning Boundaries” which are mapped resource areas used in municipal land use ordinances. Lastly, this chapter identifies historic sites which could be protected as open space, and then addresses municipal ordinances that address historic resources preservation. This chapter also includes a Historic Resources Plan for the Battlefield. This plan was developed based on an evaluation that prioritizes those parts of the Battlefield that are well suited to be studied in greater detail or protected. The Battlefield is large and includes extensive areas of developed land in which there are no existing historic structures. Even the topography of the land has been graded in many areas so that hills or swales that were present in 1777 no longer exist. To determine what areas warrant further study and protection, an analysis was conducted that focuses on historic resources such as buildings; land areas that were used by troops for camping, marching, or combat; and defining features such as villages or streams that were important to the events of the Battle. -

Chapter 7: Upland County Park Chapter 7: Upland County Park

Upland County Park 7 Volume III: County Parks and Recreation Plan Chapter 7: Upland County Park Chapter 7: Upland County Park INTRODUCTION BRIEF HISTORY The earliest relevant history of the Upland County Park area was the construction of Caleb Pusey’s house in 1638 and various mills and a race hydraulically powered by Chester Creek. The Mills created by Pusey were successful through the 1700’s even after Pusey sold them in 1709. Further development of the mills in the 1800’s, the Pusey site, on land in Upland Park and in the Upland area was directly attributed to the Crozer Family. John Price Crozer bought the mills and the Pusey tract in 1845. The Crozers’ further developed the Upland Park area to include small frame houses and a school house. John Crozer eventually turned the mills into a very profitable cotton factory with steam power. From his prospering enterprises and the ever-growing workforce associated, Crozer was able to develop the area into a village of houses and mansions, most of which have not survived to this today. One of the mansions, the George K. Crozer mansion (affectionately known as the “Netherleigh” mansion), was built in 1869 on nearly 38 acres. The Mansion included a carriage house, a springhouse, a coachman’s house, outbuildings and a barn. Today only the carriage house and the remnants of the driveway access remain as a historical relic from this time. When George K. Crozer died, the Netherleigh mansion what purchased by Dr. Israel Bram as a private sanatorium until Bram sold the 38 acre Figure 7-1: Rendering of the Netherleigh Mansion property to the Salvation Army in 1945. -

“Unveiling the Past: Current Contributions to Pennsylvania Archaeology”

1 The 90th Annual Meeting The Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology April 5-7, 2019 “Unveiling the Past: Current Contributions to Pennsylvania Archaeology” Hosted by the Mon-Yough Chapter #3 Ramada Inn by Wyndham Uniontown, Pennsylvania 2 3 The Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology, Inc. Officers Jonathan Libbon …………………………………….………………..President Jonathan A. Burns………………………………….…..First Vice-President Thomas Glover ………………………………………Second Vice-President Roger Moeller…………………………………………………………………Editor Judy Duritsa……………………………………………………………..Secretary Ken Burkett………………………………………………………………Treasurer Roger Moeller……………………………………………………….…Webmaster Directors Susanne Haney Angela Jaillett-Wentling Paul Nevin Valerie Perazio Mon-Yough Chapter #3 Officers John P. Nass, Jr. ………………………………………………………..President Susan Toia………………………………………………………….Vice-President Carl Maurer………………………………………………………………..Treasurer Phil Shandorf……………..…………………………Corresponding Secretary Douglas Corwin………………………………………………….……..Webmaster 4 Location of meeting Rooms Hospitality Suite RAMADA INN FLOOR PLAN 5 Organizing Committee Program Chair: John P. Nass, Jr. Book Room: Donald Rados Hospitality Suite Arrangements: Bob Harris and Dwayne Santella Local Arrangements: Phil Shandorf Website: Douglas Corwin Registration: Carl Maurer All PAC and SPA sessions will be held at the Ramada Inn by Wyndham Uniontown, PA MEETING INFORMATION Please Note: Titles followed by an asterisk are student papers entered in the Fred Kinsey Competition. The PAC Board and Business Meeting on Friday morning will be held in the Appalachian Ridge and Laurel Ridge Room. SPA Board Meeting on Friday evening at 6:00 pm will be in the Appalachian Ridge and Laurel Ridge Rooms. Registration Table: The Oasis Area outside of the Book Room and Lounge near the pool. The General Business Meeting on Saturday morning at 8:00 am will be in the Appalachian Ridge and Laurel Ridge Rooms. The Hospitality Suite on Friday and Saturday evenings will be in the Managers Suite, Second Floor, Room 279. -

Eddystone Borough Revitalization Study

EDDYSTONE BOROUGH REVITALIZATION STUDY Prepared by: Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission June 1990 EDDYSTONE BOROUGH REVITALIZATION STUDY Prepared by: Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission The Bourse Building Twenty-One South Fifth Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19106 June 1990 The Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) logo is adapted from the official seal of the Commission and is designed as a stylized image of the Delaware Valley. The outer ring symbolizes the region as a whole while the diagonal bar signifies the Delaware River flowing through it. The two adjoining crescents represent the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the State of New Jersey. The logo combines these elements to depict the areas served by DVRPC. Created in 1965, DVRPC provides continuing, comprehensive and coordinated planning for the orderly growth and development of the Delaware Valley region. The interstate region includes Bucks, Chester, Delaware and Montgomery counties in Pennsylvania, and the City of Philadelphia; and Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and Mercer counties in New Jersey. The Commission is an advisory agency which divides its planning and service functions between the Office of the Executive Director, the Office of Public Affairs, and four Divisions: Transportation Planning, Strategic Planning, Regional Information Services Center, and Finance and Administration. DVRPC's mission for the 1980s is to conduct high priority short term strategic studies for member governments and operating agencies, develop a long range comprehensive plan and provide technical assistance, data and services to the public and private sector. The preparation of this report was funded through federal grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation's Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA), as well as by DVRPC's member governments.