Ownership, Control, Sponsorship, and Trusteeship: Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Byzantine Coadjutor Archbishop Installed at Cathedral Reflection

Byzantine coadjutor archbishop installed at Cathedral By REBECCA C. M ERTZ I'm com ing back to m y home in Pennsylvania, Before a congregation of some 1800 persons. m arked another milestone in the history of the PITTSBURGH - In am elaborate ceremony where I have so many friends and where I've Archbishop Dolinay, 66, was welcomed into his faith of Byzantine Catholics. Tuesday at St. Paul Cathedral, Byzantine Bishop spent so m uch of m y life," Archbishop Dolinay position w ith the traditional gifts of hospitality, "Today we extend our heartfelt congratula Thom as V. Dolinay of the Van Nuys, Calif., said at the close of the cerem ony. bread, salt and the key. tions to Bishop Dolinay," Archbishop Kocisko Diocese was installed as coadjutor archbishop of As coadjutor. Archbishop Dolinay will have the The papal "bulla" appointing Archbishop said, "as we chart the course of the archdiocese the Byzantine Metropolitan Archdiocese of Pitt right of succession to Archbishop Kocisko. The Dolinay was read, and Archbishop Kocisko through the next m illenium .” sburgh. with Archbishop Stephen J. Kocisko, new archbishop, a native of Uniontown, was or recited the prayer of installation, and led A r During the liturgy that followed the installa the present leader of the Pittsburgh Archdiocese, dained to the episcopate in 1976. Before serving chbishop Dolinay to the throne. tion ceremony, Bishop Daniel Kucera, OSB, a officiating. in California, he was first auxiliary bishop of the In his welcom ing serm on. Archbishop Kocisko form er classmate of Archbishop Dolinay's at St. “I'm overjoyed in this appointment because Passaic, N .J. -

Chinese Catholic Nuns and the Organization of Religious Life in Contemporary China

religions Article Chinese Catholic Nuns and the Organization of Religious Life in Contemporary China Michel Chambon Anthropology Department, Hanover College, Hanover, IN 47243, USA; [email protected] Received: 25 June 2019; Accepted: 19 July 2019; Published: 23 July 2019 Abstract: This article explores the evolution of female religious life within the Catholic Church in China today. Through ethnographic observation, it establishes a spectrum of practices between two main traditions, namely the antique beatas and the modern missionary congregations. The article argues that Chinese nuns create forms of religious life that are quite distinct from more universal Catholic standards: their congregations are always diocesan and involved in multiple forms of apostolate. Despite the little attention they receive, Chinese nuns demonstrate how Chinese Catholics are creative in their appropriation of Christian traditions and their response to social and economic changes. Keywords: christianity in China; catholicism; religious life; gender studies Surveys from 2015 suggest that in the People’s Republic of China, there are 3170 Catholic religious women who belong to 87 registered religious congregations, while 1400 women belong to 37 unregistered ones.1 Thus, there are approximately 4570 Catholics nuns in China, for a general Catholic population that fluctuates between eight to ten million. However, little is known about these women and their forms of religious life, the challenges of their lifestyle, and their current difficulties. Who are those women? How does their religious life manifest and evolve within a rapidly changing Chinese society? What do they tell us about the Catholic Church in China? This paper explores the various forms of religious life in Catholic China to understand how Chinese women appropriate and translate Catholic religious ideals. -

NOCERCC Nwsltr December 2008

News Notes Membership Newsletter Winter 2009 Volume 36, No. 1 CONVENTION 2009 IN ALBUQUERQUE: A CONVERSATION The NOCERCC community gathers February 16-19, 2009 as the Archdiocese of Santa Fe welcomes our thirty-sixth annual National Convetion to Albuquerque. News Notes recently spoke with Rev. Richard Chiola, a member of the 2009 Convention Committee, about the upcoming convention. Fr. Chiola is director of ongoing formation of priests for the Diocese of Springfield in Illinois and pastor of St. Frances Cabrini Church in Springfield. He is also the Author of Catholicism for the Non-Catholic (Templegate Publishers, Springfield, IL, 2006). In This Issue: Convention 2009 in Albuquerque: A Conversation.................... 1&3 2009 President’s Distinguished Service Award....................... 2 2009 NOCERCC National Albuquerque, New Mexico Convention............................ 4 NEWS NOTES: Please describe the overall theme of the convention. Rev. Richard Chiola: The ministry of the Word is one of the three munera or ministries which the ordained engage in for the sake Tool Box................................. 5 of all the faithful. As the USCCB’s The Basic Plan for the Ongoing Formation of Priests indicates, each of these ministries requires a priest to engage in four dimensions of ongoing formation. The convention schedule will explore those four dimensions (the human, the spiritual, the intellectual, and the pastoral) for deeper appreciation of the complexity of the ministry of the Word. Future conventions will explore each of the other two ministries, sanctification and governance. 2009 Blessed Pope John XXIII Award.................................... 5 The 2009 convention will open with a report from Archbishop Donald Wuerl about the Synod held in the fall of 2008 on the ministry of the Word. -

Women and Men Entering Religious Life: the Entrance Class of 2018

February 2019 Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 February 2019 Mary L. Gautier, Ph.D. Hellen A. Bandiho, STH, Ed.D. Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Characteristics of Responding Institutes and Their Entrants Institutes Reporting New Entrants in 2018 ..................................................................................... 7 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Age of the Entrance Class of 2018 ................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to United States ....................................................................... 9 Race and Ethnic Background ........................................................................................................ 10 Religious Background .................................................................................................................. -

Nemes György: Az Egyháztörténet Vázlatos Áttekintése

PPEK 97 Nemes György: Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése Nemes György Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése mű a Pázmány Péter Elektronikus Könyvtár (PPEK) – a magyarnyelvű keresztény irodalom tárháza – állományában. Bővebb felvilágosításért és a könyvtárral kapcsolatos legfrissebb hírekért látogassa meg a http://www.ppek.hu internetes címet. 2 PPEK / Nemes György: Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése Impresszum Nemes György Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése Jegyzet az Egri Hittudományi Főiskola Váci Levelező Tagozatának hallgatói számára A Piarista Tartományfőnökség 320/1999. sz. engedélyével. Munkatársak: Mészáros Gábor, Nagy Attila, Nemes Rita Lektorálta: Bocsa József A Középkor című fejezet egyik része (Mohamed és az iszlám) és A magyar egyház története című fejezet három része (A kezdetektől az Árpád-kor végéig; A reformáció és a katolikus megújulás; Kitekintés) Mészáros Gábor munkája. ____________________ A könyv elektronikus változata Ez a publikáció az Egri Hittudományi Főiskola Tanárképző Szakának Váci Levelező Tagozata által megjelentetett azonos című könyv szöveghű, elektronikus változata. Az elektronikus kiadás engedélyét a szerző, Nemes György Sch.P. adta meg. Ezt az elektronikus változatot a Pázmány Péter Elektronikus Könyvtár elvei szerint korlátlanul lehet lelkipásztori célokra használni. Minden más jog a szerzőé. PPEK / Nemes György: Az egyháztörténet vázlatos áttekintése 3 Tartalomjegyzék Impresszum ............................................................................................................................... -

St. Veronica Parish Fàa Ixüéç|Vt Axãá Eastpointe, Michigan 1926-2021

March 14, 2021 St. Veronica Parish fàA ixÜÉÇ|vt axãá Eastpointe, Michigan 1926-2021 Email: [email protected] Website: stveronica.weconnect.com Our 95th Year Congratulations to Our Confirmandi! Jordin Adkins Enrique Allor Cole Foster Lucy Foster Nathaniel Masty Emma Pawlowski Magdalen Pawlowski Emma Stafford Brady Winbigler Welcome Bishop Donald Hanchon! Knights of Columbus Leo XIII Council 3042 Carry Out Pancake Breakfast Palm Sunday, March 28, 2021 Pancakes, Krusteaz Belgian Waffles, Eggs and Sausage begins at 9:00a.m. Carry Out or Drive Thru Only Adults $6.00 Seniors $5.00 Children $4.00 Children Under 6 FREE The Easter Bunny and Snow Princess, Anna and Elsa, will be giving goodie bags to all the children. Bring your camera! Net Proceeds to Sr. Marcine Food Pantry Payable by Cash or Personal Check Only - Sorry-No Credit Cards at this Time St. Veronica News, Eastpointe Page 2 Liturgies Anniversary of Death, Josephine Saturday, March 13 Jones Birthday Remembrance, and Vigil: Fourth Sunday of Lent For Our Parents, Norman and Ann 4:30p.m. Kevin Stocker by Stocker Porter by Janet Porter, Christine Diamond by Dennis Brill, George W. Family, Christine Diamond by Lienau 2nd Anniversary of Death Dennis Brill, Joseph Hojnacki 29th and Lillian Sabados 16th Anniversary Anniversary of Death by Jim and of Death by Family and Friends, Gail Pachla, Betty Schroeder 6th Anniversary of Death by Family, Leonita M. Diegel 33rd Anniversary Stations of the Cross Marie Toerper 20th Anniversary of of Death by Son, David Diegel, Birthday Blessings for Josephine and Benediction Death by Sharon Toerper, Michael Pokladek Birthday Remembrance Mazur on her 91st Birthday by Family Every Wednesday of Lent Sunday, March 21 by Shirley and Debra Garofalo, at 4:30p.m. -

The Ecumenical Movement and the Origins of the League Of

IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by James M. Donahue __________________________ Mark A. Noll, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana April 2015 © Copyright 2015 James M. Donahue IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 Abstract by James M. Donahue This dissertation traces the origins of the League of Nations movement during the First World War to a coalescent international network of ecumenical figures and Protestant politicians. Its primary focus rests on the World Alliance for International Friendship Through the Churches, an organization that drew Protestant social activists and ecumenical leaders from Europe and North America. The World Alliance officially began on August 1, 1914 in southern Germany to the sounds of the first shots of the war. Within the next three months, World Alliance members began League of Nations societies in Holland, Switzerland, Germany, Great Britain and the United States. The World Alliance then enlisted other Christian institutions in its campaign, such as the International Missionary Council, the Y.M.C.A., the Y.W.C.A., the Blue Cross and the Student Volunteer Movement. Key figures include John Mott, Charles Macfarland, Adolf Deissmann, W. H. Dickinson, James Allen Baker, Nathan Söderblom, Andrew James M. Donahue Carnegie, Wilfred Monod, Prince Max von Baden and Lord Robert Cecil. -

Madonna Now President's Report 2012-2013

MADONNA NOW The Magazine of Madonna University PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2012 & 2013 LIVING OUR VALUES On campus, in our community and around the world Thank You to our Generous Sponsors of the 2012 Be Polish for a Night IRA Charitable Rollover Extended Scholarship Dinner and Auction A great way to give to Madonna! If you’re 70 ½ or over, you can make a Diamond Sponsors – $5,000 GoldCorp Inc. tax free gift from your IRA: MJ Diamonds • Direct a qualified distribution (up to $100,000) directly to Madonna Platinum Sponsor – $2,500 • This counts toward your required minimum distribution Felician Sisters of North America • You’ll pay no federal income tax on the distribution Lorraine Ozog • Your gift makes an immediate impact at Madonna Gold Sponsor – $1,000 Comerica Contact us to discuss programs and initiatives DAK Solutions you might want to support. Doc’s Sports Retreat Dean Adkins, Director of Gift Planning Dunkin Donuts/BP Friends of Representative Lesia Liss 734-432-5856 • [email protected] Laurel Manor Miller Canfield Polish National Alliance Lodge 53 Linda Dzwigalski-Long Daniel and Karen Longeway Ray Okonski and Suzanne Sloat SHOW YOUR Leonard C. Suchyta MADONNA PRIDE! Rev. Msgr. Anthony M. Tocco Leave your mark at Madonna with a CBS 62 Detroit/CW50 Legacy Brick in the Path of the Madonna Silver Sponsor – $500 or get an Alumni Spirit Tassel Catholic Vantage Financial Marywood Nursing Center Bricks with your personalized Schakolad Chocolate Factory message are $150 for an 8x8 with SmithGroupJJR Stern Brothers & Co. M logo, and $75 for a 4x8. Spirit Tassels are only $20.13 Bronze Sponsor – $250 Paul and Debbie DeNapoli E & L Construction FOCUS Facility Consulting Services Inc Dr. -

October / November 2011 Newsletter

October / November 2011 Thaddeus Mirecki 30th Anniversary of Polish American Heritage Month 2011 “Pride of Polonia Award” Recipient The Polish American Heritage Month On Sunday, September 3, 2011, at Committee urges all Polish Americans, the conclusion of the 12:30 P.M. Mass organizations, cultural and youth groups, at the National Shrine of Our Lady of churches and schools to make a special Czestochowa in Doylestown, PA, the Polish effort to highlight the history, traditions Apostolate Pride of Polonia Award was and culture of the Polish people during presented to Thaddeus Mirecki by Rev. October. During 2011, Polonia marks Joseph Olczak, O.S.P.P.E., Provincial, the 30th anniversary of Polish American Pauline Fathers and Brothers, on behalf of Heritage Month, founded in Philadelphia Cardinal Adam Maida and Msgr. Anthony and now a national effort promoting Polish Czarnecki, National Chairman of the Polish American accomplishments and Polish Irene and Ted Mirecki Apostolate Committee. American communities across the U.S.A. The Pride of Polonia Award was established in 1992 by the The national theme "United We Executive Board of the Polish Apostolate to recognize individuals who Celebrate" helps brings attention to the fact that we celebrate our make unique contributions to the Polish people and are involved in Polish Heritage while living with many nationalities in the greatest philanthropic activites. The first recipient was John Cardinal Krol. country on earth. Because our ancestors were proud of their Mr. Mirecki thanked the Committee and gave his deepest thanks to Polish heritage, the more than 20 million people in America that his wife of 44 years, Irene, whose patience and encouragement made share full or partial Polish heritage continue to honor the customs it possible for him to be involved in causes so dear to him. -

The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2017 Lux Occidentale: The aE stern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933 Michael Anthony Guzik University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Guzik, Michael Anthony, "Lux Occidentale: The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical ommiC ssion for Russia, Origins to 1933" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1632. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1632 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2017 ABSTRACT LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Neal Pease Although it was first a sub-commission within the Congregation for the Eastern Churches (CEO), the Pontifical Commission for Russia (PCpR) emerged as an independent commission under the presidency of the noted Vatican Russian expert, Michel d’Herbigny, S.J. in 1925, and remained so until 1933 when it was re-integrated into CEO. -

131825-Memory-Folder.Pdf

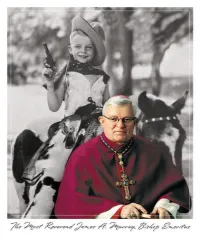

During the Great Depression in the mid-sized Michigan town of Jackson, James and Clare Murray welcomed their third son, James on July 5, 1932. His early years were spent playing baseball and running around with his two older brothers, Bill and Jack. He attended St. Mary Catholic Elementary school and was taught by the Sisters of Charity. Jim was naturally left-handed and was fond of retelling the story of the Sisters calling his mom to school concerned about this. She told them, “We know Jim’s a little off, but we like him that way.” And so he remained left-handed and was known throughout his life for his beautiful penmanship. As evidenced by his St. Mary’s High School yearbook (which he served as editor), Jim excelled both academically and also participated in many extracurricular activities including baseball, boxing, the Glee Club, chairman of the Prom Committee and, not surprisingly, was elected Senior Class President at St. Mary High School. During those days he recounted that he had ideas of becoming a priest, but also entertained thoughts of being a doctor or a lawyer. The calling to the Priesthood won out and Jim studied at Sacred Heart Seminary where he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree and at St. John Seminary, Plymouth earning a Bachelor of Theology degree. He was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Lansing by Bishop Joseph H. Albers on June 7, 1958 at St. Mary Cathedral, Lansing. He celebrated his first Mass in his hometown of Jackson at St. Mary Parish and was assisted by long-time friend Fr. -

New Chaplain Strengthens Latin Mass Community

50¢ March 9, 2008 Volume 82, No. 10 www.diocesefwsb.org/TODAY Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend TTODAYODAY’’SS CCATHOLICATHOLIC Springing forward New chaplain strengthens Daylight Saving Time begins Latin Mass community March 9; get to Mass on time Baptism dilemma BY DON CLEMMER Using wrong words FORT WAYNE — Father George Gabet discovered ruled not valid his love for the old Latin Mass years before his ordi- nation while attending it at Sacred Heart Parish in Fort Page 5 Wayne. Now he will be serving Sacred Heart, as well as Catholics in South Bend, through his new assign- ment as a chaplain of a community formed especially for Catholics who worship in the pre-Vatican II rite. This rite, called the 1962 Roman Missal, the Award winning Tridentine Rite and, more recently, the extraordinary teachers form of the Roman Missal, has received greater atten- tion since the July 2007 publication of Pope Benedict Theology teachers XVI’s motu proprio, “Summorum Pontificum,” allowed for greater use of it. cited for gifts To meet the needs of Catholics wishing to worship in this rite in the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Page 10 Bishop John M. D’Arcy has established the St. Mother Theodore Guérin Community. This community, which came into effect March 1, will consist of parishioners at Sacred Heart in Fort Wayne and St. John the Baptist Vices and virtues in South Bend, two parishes that have offered the Tridentine rite Mass since 1990. Father George Gabet Envy and sloth explored will be the community’s chaplain.