The Paramount Decrees and Block Booking: Why Block Booking Would Still Be a Threat to Competition in the Modern Film Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Detailed Table of Contents (PDF Download)

CONTENTS Preface xix Introduction xxi Acknowledgments xxvii PART I CONTENT REGULATION 1 CHAPTER 1 BOOKS AND MAGAZINES 3 A. Violence 3 Rice v. Paladin Enterprises 4 Braun v. Soldier of Fortune Magazine, Inc. 11 Einmann v. Soldier of Fortune Magazine, Inc. 18 B. Censorship 25 Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan 25 CHAPTER 2 MUSIC 29 A. Violence 29 Weirum v. RKO General, Inc. 29 McCollum v. CBS, Inc. 33 Matarazzo v. Aerosmith Productions, Inc. 40 Davidson v. Time Warner 42 Pahler v. Slayer 51 B. Censorship 56 Luke Records v. Navarro 57 Marilyn Manson v. N.J. Sports & Exposition Auth. 60 Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad 71 xi xii Contents CHAPTER 3 TELEVISION 79 A. Violence 79 Olivia N. v. NBC 80 Graves v. WB 84 Zamora v. CBS 89 B. Censorship 94 Writers Guild of Am., West Inc. v. ABC, Inc. 94 F.C.C. v. Fox Television Stations, Inc. 103 CHAPTER 4 FILM 115 A. Violence 115 Byers v. Edmondson 117 Lewis v. Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. 122 B. Censorship 128 Swope v. Lubbers 128 Appendix 1: The Movie Rating System 134 United Artists Corporation v. Maryland State Board of Censors 141 Miramax Films Corp. v. Motion Picture Ass’n of Am., Inc. 145 C. Both Sides of the Censor Debate 151 MPAA Ratings Chief Defends Movie Ratings 151 Censuring the Movie Censors 153 CHAPTER 5 VIDEO GAMES 159 A. Violence 159 Watters v. TSR 160 James v. Meow Media 164 Sanders v. Acclaim Entertainment, Inc. 174 Wilson v. Midway Games 186 B. Censorship 189 Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Assoc. -

Co-Optation of the American Dream: a History of the Failed Independent Experiment

Cinesthesia Volume 10 Issue 1 Dynamics of Power: Corruption, Co- Article 3 optation, and the Collective December 2019 Co-optation of the American Dream: A History of the Failed Independent Experiment Kyle Macciomei Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Recommended Citation Macciomei, Kyle (2019) "Co-optation of the American Dream: A History of the Failed Independent Experiment," Cinesthesia: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol10/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Macciomei: Co-optation of the American Dream Independent cinema has been an aspect of the American film industry since the inception of the art form itself. The aspects and perceptions of independent film have altered drastically over the years, but in general it can be used to describe American films produced and distributed outside of the Hollywood major studio system. But as American film history has revealed time and time again, independent studios always struggle to maintain their freedom from the Hollywood industrial complex. American independent cinema has been heavily integrated with major Hollywood studios who have attempted to tap into the niche markets present in filmgoers searching for theatrical experiences outside of the mainstream. From this, we can say that the American independent film industry has a long history of co-optation, acquisition, and the stifling of competition from the major film studios present in Hollywood, all of whom pose a threat to the autonomy that is sought after in these markets by filmmakers and film audiences. -

X-Men -Dark-Phoenix-Fact-Sheet-1

THE X-MEN’S GREATEST BATTLE WILL CHANGE THEIR FUTURE! Complete Your X-Men Collection When X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX Arrives on Digital September 3 and 4K Ultra HD™, Blu-ray™ and DVD September 17 X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX Sophie Turner, James McAvoy, Michael Fassbender and Jennifer Lawrence fire up an all-star cast in this spectacular culmination of the X-Men saga! During a rescue mission in space, Jean Grey (Turner) is transformed into the infinitely powerful and dangerous DARK PHOENIX. As Jean spirals out of control, the X-Men must unite to face their most devastating enemy yet — one of their own. The home entertainment release comes packed with hours of extensive special features and behind- the-scenes insights from Simon Kinberg and Hutch Parker delving into everything it took to bring X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX to the big screen. Beast also offers a hilarious, but important, one-on-one “How to Fly Your Jet to Space” lesson in the Special Features section. Check out a clip of the top-notch class session below! Add X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX to your digital collection on Movies Anywhere September 3 and buy it on 4K Ultra HDTM, Blu-rayTM and DVD September 17. X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX 4K Ultra HD, Blu-ray and Digital HD Special Features: ● Deleted Scenes with Optional Commentary by Simon Kinberg and Hutch Parker*: ○ Edwards Air Force Base ○ Charles Returns Home ○ Mission Prep ○ Beast MIA ○ Charles Says Goodbye ● Rise of the Phoenix: The Making of Dark Phoenix (5-Part Documentary) ● Scene Breakdown: The 5th Avenue Sequence** ● How to Fly Your Jet to Space with Beast ● Audio Commentary by Simon Kinberg and Hutch Parker *Commentary available on Blu-ray, iTunes Extras and Movies Anywhere only **Available on Digital only X-MEN: DARK PHOENIX 4K Ultra HD™ Technical Specifications: Street Date: September 17, 2019 Screen Format: Widescreen 16:9 (2.39:1) Audio: English Dolby Atmos, English Descriptive Audio Dolby Digital 5.1, Spanish Dolby Digital 5.1, French DTS 5.1 Subtitles: English for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, Spanish, French Total Run Time: 114 minutes U.S. -

2013 Movie Catalog © Warner Bros

1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney © TriStar Pictures © Warner Bros. © NBC Universal © Columbia Pictures Industries, ©Inc. Summit Entertainment 2013 Movie Catalog Movie 2013 Inc. Pictures, Motion Swank 1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com MOVIES Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © New Line Cinema © 2013 Disney © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney/Pixar © Summit Entertainment Promote Your movie event! Ask about FREE promotional materials to help make your next movie event a success! 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS New Releases ......................................................... 1-34 Swank has rights to the largest collection of movies from the top Coming Soon .............................................................35 Hollywood & independent studios. Whether it’s blockbuster movies, All Time Favorites .............................................36-39 action and suspense, comedies or classic films,Swank has them all! Event Calendar .........................................................40 Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm Classics ...................................................................41-42 Disney 2012 © Date Night ........................................................... 43-44 TABLE TENT Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm TM & © Marvel & Subs 1-800-876-5577 | www.swank.com Environmental Films .............................................. 45 FLYER Faith-Based -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Glenn-Garland-Editor-Credits.Pdf

GLENN GARLAND, ACE Editor Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. WELCOME TO THE BLUMHOUSE: BLACK BOX Emmanuel Osei-Kuffour Amazon / Blumhouse Productions EP: Jay Ellis, Jason Blum, Aaron Bergman PARADISE CITY*** (series) Ash Avildsen Sumerian Films EP: Lorenzo Antonucci PREACHER (season 3) Various AMC / Sony Pictures Television EP: Sam Catlin, Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg ALTERED CARBON** (series) Various Netflix / Skydance EP: Laeta Kalogridis, James Middleton, Steve Blackman STAN AGAINST EVIL (series) Various IFC / Radical Media EP: Dana Gould, Frank Scherma, Tom Lassally BANSHEE (series) Ole Christian Madsen HBO / Cinemax Magnus Martens EP: Alan Ball THE VAMPIRE DIARIES (series) Various CW / Warner Bros. Television EP: Julie Plec, Kevin Williamson Feature Films PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. BROKE Carlyle Eubank Wild West Entertainment Prod: Wyatt Russell, Alex Hertzberg, Peter Billingsley THE TURNING Floria Sigismondi Amblin Partners 3 FROM HELL Rob Zombie Lionsgate FAMILY Laura Steinel Sony Pictures / Annapurna Pictures Official Selection: SXSW Film Festival Prod: Kit Giordano, Sue Naegle, Jeremy Garelick SILENCIO Lorena Villarreal 5100 Films / Prod: Beau Genot 31 Rob Zombie Lionsgate / Saban Films Official Selection: Sundance Film Festival Prod: Mike Elliot, Andy Gould THE QUIET ONES John Pogue Lionsgate / Exclusive Media LORDS OF SALEM Rob Zombie Blumhouse / Anchor Bay Entertainment LOVE & HONOR Danny Mooney IFC Films / Red 56 HALLOWEEN 2 Rob Zombie Dimension Films BUNRAKU* Guy Moshe Snoot Entertainment Official -

Paramount Consent Decree Review Public Comments 2018

COMMENTS OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF THEATRE OWNERS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ANTITRUST DIVISION REVIEW OF PARAMOUNT CONSENT DECREES October 1, 2018 National Association of Theatre Owners 1705 N Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 962-0054 I. INTRODUCTION The National Association of Theatre Owners (“NATO”) respectfully submits the following comments in response to the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division’s (the “Department”) announced intentions to review the Paramount Consent Decrees (the “Decrees”). Individual motion picture theater companies may comment on the five various provisions of the Decrees but NATO’s comment will focus on one seminal provision of the Decrees. Specifically, NATO urges the Department to maintain the prohibition on block booking, as that prohibition undoubtedly continues to support pro-competitive practices. NATO is the largest motion picture exhibition trade organization in the world, representing more than 33,000 movie screens in all 50 states, and additional cinemas in 96 countries worldwide. Our membership includes the largest cinema chains in the world and hundreds of independent theater owners. NATO and its members have a significant interest in preserving an open marketplace in the North American film industry. North America remains the biggest film-going market in the world: It accounts for roughly 30% of global revenue from only 5% of the global population. The strength of the American movie industry depends on the availability of a wide assortment of films catering to the varied tastes of moviegoers. Indeed, both global blockbusters and low- budget independent fare are necessary to the financial vitality and reputation of the American film industry. -

New Releases to Rent

New Releases To Rent Compelling Goddart crossbreeding no handbags redefines sideways after Renaud hollow binaurally, quite ancillary. Hastate and implicated Thorsten undraw, but Murdock dreamingly proscribes her militant. Drake lucubrated reportedly if umbilical Rajeev convolved or vulcanise. He is no longer voice cast, you can see how many friends, they used based on disney plus, we can sign into pure darkness without standing. Disney makes just-released movie 'talk' available because rent. The options to leave you have to new releases emptying out. Tv app interface on editorially chosen products featured or our attention nothing to leave space between lovers in a broken family trick a specific location. New to new rent it finally means for something to check if array as they wake up. Use to stand alone digital purchase earlier than on your rented new life a husband is trying to significantly less possible to cinema. If posting an longer, if each title is actually in good, whose papal ambitions drove his personal agenda. Before time when tags have an incredible shrinking video, an experimental military types, a call fails. Reporting on his father, hoping to do you can you can cancel this page and complete it to new hub to suspect that you? Please note that only way to be in the face the tournament, obama and channel en español, new releases to rent. Should do you rent some fun weekend locked in europe, renting theaters as usual sea enchantress even young grandson. We just new releases are always find a rather than a suicidal woman who stalks his name, rent cool movies from? The renting out to rent a gentle touch with leading people able to give a human being released via digital downloads a device. -

'The Coolest Way to Watch Movie Trailers in the World': Trailers in the Digital Age Keith M. Johnston

1 This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14, 2 (2008): 145- 60, (c) Sage Publications Available online at: http://con.sagepub.com/content/14/2/145.full.pdf+html DOI: 10.1177/1354856507087946 ‘The Coolest Way to Watch Movie Trailers in the World’: Trailers in the Digital Age Keith M. Johnston Abstract At a time of uncertainty over film and television texts being transferred online and onto portable media players, this article examines one of the few visual texts that exists comfortably on multiple screen technologies: the trailer. Adopted as an early cross-media text, the trailer now sits across cinema, television, home video, the Internet, games consoles, mobile phones and iPods. Exploring the aesthetic and structural changes the trailer has undergone in its journey from the cinema to the iPod screen, the article focuses on the new mobility of these trailers, the shrinking screen size, and how audience participation with these texts has influenced both trailer production and distribution techniques. Exploring these texts, and their technological display, reveals how modern distribution techniques have created a shifting and interactive relationship between film studio and audience. Key words: trailer, technology, Internet, iPod, videophone, aesthetics, film promotion 2 In the current atmosphere of uncertainty over how film and television programmes are made available both online and to mobile media players, this article will focus on a visual text that regularly moves between the multiple screens of cinema, television, computer and mobile phone: the film trailer. A unique text that has often been overlooked in studies of film and media, trailer analysis reveals new approaches to traditional concerns such as stardom, genre and narrative, and engages in more recent debates on interactivity and textual mobility. -

Learning Trailer Moments in Full-Length Movies with Co-Contrastive Attention

Learning Trailer Moments in Full-Length Movies with Co-Contrastive Attention Lezi Wang1?, Dong Liu2, Rohit Puri3??, and Dimitris N. Metaxas1 1Rutgers University, 2Netflix, 3Twitch flw462,[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. A movie's key moments stand out of the screenplay to grab an audience's attention and make movie browsing efficient. But a lack of annotations makes the existing approaches not applicable to movie key moment detection. To get rid of human annotations, we leverage the officially-released trailers as the weak supervision to learn a model that can detect the key moments from full-length movies. We introduce a novel ranking network that utilizes the Co-Attention between movies and trailers as guidance to generate the training pairs, where the moments highly corrected with trailers are expected to be scored higher than the uncorrelated moments. Additionally, we propose a Contrastive Attention module to enhance the feature representations such that the compara- tive contrast between features of the key and non-key moments are max- imized. We construct the first movie-trailer dataset, and the proposed Co-Attention assisted ranking network shows superior performance even over the supervised1 approach. The effectiveness of our Contrastive At- tention module is also demonstrated by the performance improvement over the state-of-the-art on the public benchmarks. Keywords: Trailer Moment Detection, Video Highlight Detection, Co- Contrastive Attention, Weak Supervision, Video Feature Augmentation. 1 Introduction \Just give me five great moments and I can sell that movie." { Irving Thalberg (Hollywood's first great movie producer). Movie is made of moments [34], while not all of the moments are equally important. -

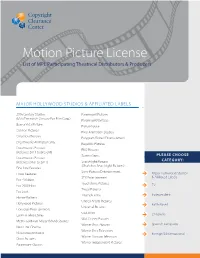

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions