The 1981 Kosovar Uprising: Nation and Facework By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Movements: 1968, 1981 and 1997 the Impact Of

Student Movements: 1968, 1981 and 1997 The impact of students in mobilizing society to chant for the Republic of Kosovo Atdhe Hetemi Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of East European Languages and Cultures Supervisor Prof. dr. Rozita Dimova Department of East European Languages and Cultures Dean Prof. dr. Gita Deneckere Rector Prof. dr. Rik Van de Walle October 2019 i English Summary This dissertation examines the motives and central visions of three student demonstrations, each taking place within different historical and political contexts and each organized by a different generation of Kosovo Albanian students. The years 1968, 1981 and 1997 witnessed a proliferation of student mobilizations as collective responses demanding more national rights for Albanians in Kosovo. I argue that the students' main vision in all three movements was the political independence of Kosovo. Given the complexity of the students' goal, my analysis focuses on the influence and reactions of domestic and foreign powers vis-à-vis the University of Prishtina (hereafter UP), the students and their movements. Fueled by their desire for freedom from Serbian hegemony, the students played a central role in "preserving" and passing from one generation to the next the vision of "Republic" status for Kosovo. Kosova Republikë or the Republic of Kosovo (hereafter RK) status was a demand of all three student demonstrations, but the students' impact on state creation has generally been underestimated by politicians and public figures. Thus, the primary purpose of this study is to unearth the various and hitherto unknown or hidden roles of higher education – then the UP – and its students in shaping Kosovo's recent history. -

Yugoslav "Self-Administration" a Capitalist Theory and Practice

The electronic version of the book is created by http://www.enverhoxha.ru WORKERS OF ALL COUNTRIES, UNITE! ENVER HOXHA YUGOSLAV "SELF-ADMINISTRATION" - A CAPITALIST THEORY AND PRACTICE (against E. Kardelj's anti- socialist views expressed in the book «Directions of the Deve• lopment of the Political System of Socialist Self-administra• tion») THE INSTITUTE OF MARXIST-LENINIST STUDIES AT THE CC OF THE PLA THE «8 NËNTORI» PUBLISHING HOUSE TIRANA, 1978 A great deal of publicity is being given to a book published in Yugoslavia last year under the title «Directions of the Development of the Politi• cal System of Socialist Self-administration», by the leading «theoretician» of Titoite revisionism, Eduard Kardelj. The anti-Marxist ideas of this book were the basis of the entire proceedings of the 11th Con• gress of the revisionist party of Yugoslavia, to which the Titoites, in an effort to disguise its bourgeois character, have given the name: «The League of Communists of Yugoslavia». As the 7th Congress of the PLA pointed out, the Titoites and international capitalism are pub• licizing the system of «self-administration» as «a ready-made and tested road to socialism», and are using it as a favourite weapon in their struggle against socialism, the revolution and li• beration struggles. In view of its danger, I think I must express some opinions about this book. As is known, capitalism has been fully estab• lished in Yugoslavia, but this capitalism is cun• ningly disguised. Yugoslavia poses as a socialist State, but one of a special kind, which the world has never seen before! Indeed, the Titoites even boast that their State has nothing in common with the first socialist State which emerged from the October Socialist Revolution and which was founded by Lenin and Stalin on the basis of the scientific theory of Marx and Engels. -

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.)

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History August 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract This thesis examines French relations with Yugoslavia in the twentieth century and its response to the federal republic’s dissolution in the 1990s. In doing so it contributes to studies of post-Cold War international politics and international diplomacy during the Yugoslav Wars. It utilises a wide-range of source materials, including: archival documents, interviews, memoirs, newspaper articles and speeches. Many contemporary commentators on French policy towards Yugoslavia believed that the Mitterrand administration’s approach was anachronistic, based upon a fear of a resurgent and newly reunified Germany and an historical friendship with Serbia; this narrative has hitherto remained largely unchallenged. Whilst history did weigh heavily on Mitterrand’s perceptions of the conflicts in Yugoslavia, this thesis argues that France’s Yugoslav policy was more the logical outcome of longer-term trends in French and Mitterrandienne foreign policy. Furthermore, it reflected a determined effort by France to ensure that its long-established preferences for post-Cold War security were at the forefront of European and international politics; its strong position in all significant international multilateral institutions provided an important platform to do so. -

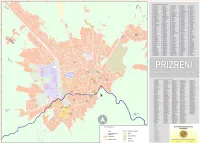

Map Data from the City of Prizren For

1 E E 3 <*- * <S V to v-v % X % 5.- ^s RADHITJA E EMRAVE SIPAS ALFABETIT -> 42 8 Marsi-7D 443 Brigáda 126-4C 347 Hysen Rexhepi-6E7E 253 Milan Šuflai-3H 218 Shaip Zurnaxhiu-4F 187 Abdy Beqiri-4E 441 Brigáda 128- 234 Hysen Trpeza-2E H 356 Mimar Sinan-6E 133 Shat Kulla-6E 1 Adem Jasharí-6E,5F 20 Bubulina-1A 451 Hysni Morína-3B 467 Mojsi Golemi-2A, 2B 424 Shefqet Berisha-80 | 360 Adnan Krasniqi-7E 97 Bujana-2D 46 Hysni Temaj- 25 Molla e Kuqe 390 Sheh Emini-7D 310 Adriatiku-5F 327 Bujar Godeni-6E 127 Ibrahim Lutfiu-6D 72 Mon Karavidaj-3C3D 341 Shn Albani-7F 38 Afrim Bytygi-1B,2B 358 Bujtinat-6E, 7E 259 Ibrahim ThagiSH 184 Morava-4E \J336 Shn Flori-6F, 7F 473 Afrim Krasniqi-9C 406 Burími-8D 45 Idriz Behluli- 23 Mreti Gllauk-1A \~345 Shn Jeronimi 1 444 Afrim Stajku-4C 261 Bushatlinjt-2H 39 llir Hoxha-1B 265 Muhamet Cami~3H 284 SherifAg TurtullaSG 446 Agim Bajrami-4C 140 Byrhan Shporta-6D 233 llirt-2E 21 Muhamet Kabashi-1A 29 Shestani | 278 Agim ShalaSF 47 Camilj Siharic 359 lljaz Kuka-6E,7E 251 Muharrem Bajraktarí-2H,3E 243 Shime Deshpali-2E 194 Agron Bytyqi-4E 56 Cesk Zadeja-3C 381 Indrit Cara -Kavaja-6D, 7D 74 Muharrem Hoxhaj-3C 291 Shkelzen DragajSF 314 Ahmet KorenicaSF 262 Dalmatt-3H 86 Isa Boletini-4D 458 Muharrem Samahoda-3B 199 Shkodra-3E \~286 293 Ahmet KrasniqiSF 475 Dardant-9C Islám Spahiu-5G l 316 MuhaxhirtSF \428 Shkronjat-7C, 7D 207 \Ahmet Prístina-5F4F 5 De Rada-6D, 5D \~7 Ismail Kryeziu-5D,4D 60 Mujo Ulqinaku-3C 138 Shote Galica-6D 447 Ajahidet-4C 61 Dd Gjon Luli-3C 40 Ismail Qemali-2B 1 69 Murat Kab ashi-4F, 5E 392 Shpend Berisha-7E -

“Eck International Journal”

ISSN: 2410-7271 KDU: 33/34 (5) Volume 4-5/ Number: 4-5/ Decembre 2016 “ECK INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL” Managment, Business, Economics and Law SCIENCE JOURNAL No.: 4-5/2016 December, 2016 Prishtina Editorial: EUROPEAN COLLEGE OF KOSOVO ECK-PRESS Editorial Board: Prof. Dr. Qerim QERIMI Prof. Dr. Enver MEHMETI Prof. Dr. Afrim LOKU The Editorial Journal: Prof. Dr. Hazër SUSURI Prof. Dr. Naim BAFTIU Prof. Phd. Cand. Miranda GASHI Editor: Prof. Dr. Ali Bajgora Copies: 300 __________________________________________________ SCIENCE JOURNAL Përmbajtja / Content 1. COLONIZING AGRARIAN REFORM IN KOSOVO – FROM BALKAN WARS TO WORLD WAR II Prof. Dr. Musa LIMANI .................................................................................. 5 European Collage of Kosovo 2.CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUES OF MINORITY COMMUNITIES IN KOSOVO Prof. Dr. Hazër SUSURI ............................................................................... 25 European Collage of Kosovo 3. APPLICATION OF DATA SECURITY FOR CHILDREN FROM INTERNET Naim BAFTIU ............................................................................................... 35 European College of Kosovo 4. ALBANIANS THROUGH THE PROLONGED TRANSITION IN THE BALKANS Prof. Dr. Avni Avdiu ..................................................................................... 45 European College of Kosovo 5. CULTURAL HERITAGE AND POLITICAL INFLUENCES IN FAVOR AND FALSIFICATION OF RELIGIOUS MONUMENTS Dr. Pajazit Hajzeri MA. Enis Kelmendi ...................................................................................... -

Yugoslav Destruction After the Cold War

STASIS AMONG POWERS: YUGOSLAV DESTRUCTION AFTER THE COLD WAR A dissertation presented by Mladen Stevan Mrdalj to The Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Political Science Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2015 STASIS AMONG POWERS: YUGOSLAV DESTRUCTION AFTER THE COLD WAR by Mladen Stevan Mrdalj ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December 2015 2 Abstract This research investigates the causes of Yugoslavia’s violent destruction in the 1990’s. It builds its argument on the interaction of international and domestic factors. In doing so, it details the origins of Yugoslav ideology as a fluid concept rooted in the early 19th century Croatian national movement. Tracing the evolving nationalist competition among Serbs and Croats, it demonstrates inherent contradictions of the Yugoslav project. These contradictions resulted in ethnic outbidding among Croatian nationalists and communists against the perceived Serbian hegemony. This dynamic drove the gradual erosion of Yugoslav state capacity during Cold War. The end of Cold War coincided with the height of internal Yugoslav conflict. Managing the collapse of Soviet Union and communism imposed both strategic and normative imperatives on the Western allies. These imperatives largely determined external policy toward Yugoslavia. They incentivized and inhibited domestic actors in pursuit of their goals. The result was the collapse of the country with varying degrees of violence. The findings support further research on international causes of civil wars. -

Albania Pocket Guide

museums albania pocket guide your’s to discover Albania theme guides Museums WELCOME TO ALBANIA 4 National Historic Museum was inaugurated on 28 October 1981. It is the biggest Albanian museum institution. There are 4750 objects inside the museum. Striking is the Antiquity Pavilion starting from the Paleolithic Period to the Late Antiquity, in the 4th century A.D., with almost 400 first class objects. The Middle Age Pavilion, with almost 300 objects, documents clearly the historical trans- formation process of the ancient Illyrians into early Arbers. CONTENTS i 5 TIRANA 6 DURRES 14 ELBASAN 18 LUSHNJE 20 KRUJE 20 APOLLONIA 26 VLORA 30 KORÇA 34 GJIROKASTRA 40 BERATI 42 BUTRINTI 46 LEZHE 50 SHKODER 52 DIBER 60 NATIONAL HISTORIC MUSEUMS TIRANA 6 National Historic Museum was inaugurated on 28 October 1981. It is the biggest Albanian museum institution. Pavilion starting from the Paleolithic Period to the Late Antiquity, in the 4th century A.D., with almost 400 first class objects. The Middle Age Pavilion, with almost 300 objects, documents clearly the historical transformation process of the ancient Illyrians into early Arbers. This pavilion reflects the Albanian history until the 15th century. Other pavilions are those of National Renaissance, Independence and Albanian State Foundation, until 1924. The Genocide Pavilion with 136 objects was founded in 1996. The Iconography Pavilion with 65 first class icons was established in 1999. The best works of 18th and 19th century painters are found here, like Onufër Qiprioti, Joan Çetiri, Kostandin Jermonaku, Joan Athanasi, Kostandin Shpataraku, Mihal Anagnosti and some un- known authors. In 2004 the Antifascism Pavilion 220 objects was reestablished. -

Msc Programme in Urban Management and Development Rotterdam, the Netherlands September 2017 Thesis Road Safety in Prishtina

MSc Programme in Urban Management and Development Rotterdam, The Netherlands September 2017 Thesis Road Safety in Prishtina: A Study of Perception from Producers’ and Road Users’ Perspectives Name : Yulia Supervisor : Linda Zuijderwijk Specialization : Urban Strategic and Planning (USP) UMD 13 Road Safety in Prishtina: A Study of Perception from Producers’ and Road Users’ Perspectives i MASTER’S PROGRAMME IN URBAN MANAGEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT (October 2016 – September 2017) Road safety in Prishtina, Kosovo: A study of perception from producers’ and road users’ perspectives Yulia Supervisor: Linda Zuijderwijk UMD 13 Report number: 1041 Rotterdam, September 2017 Road Safety in Prishtina: A Study of Perception from Producers’ and Road Users’ Perspectives ii Summary Prishtina is the capital city of Kosovo, the youngest country in Europe, who declared its independence in 2008. Before its independence, Kosovo is an autonomous province under Serbia, which was part of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). Kosovo has a long history of conflicts since the occupation of Turkish Ottoman Empire in Balkan Peninsula area until the recent one was the Kosova War in 1998 – 1999. As a post-conflict society, Prishtina is suffering from several urban challenges. One of these challenges is road safety issue indicated by increasing the number of traffic accidents in Prishtina and even nationwide. National government considered this situation as unusual for European countries. This study aimed to answer a research question on how the road safety is perceived from two main perspectives, which are road users (pedestrians and cyclists) and stakeholders in the producer’s level of road safety strategy in Prishtina. This study was conducted in urban zone of Prishtina, which is also the case study, with the regards to the increasing number of traffic accidents, which involve pedestrians and cyclists, as the vulnerable road users. -

Faded Memories

Faded Memories Life and Times of a Macedonian Villager 1 The COVER PAGE is a photograph of Lerin, the main township near the villages in which many of my family ancestors lived and regularly visited. 2 ACKNOWLEGEMENTS This publication is essentially an autobiography of the life and times of my father, John Christos Vellios, Jovan Risto Numeff. It records his recollections, the faded memories, passed down over the years, about his family ancestors and the times in which they lived. My father personally knew many of the people whom he introduces to his readers and was aware of more distant ancestors from listening to the stories passed on about them over the succeeding generations. His story therefore reinforces the integrity of oral history which has been used since ancient times, by various cultures, to recall the past in the absence of written, documentary evidence. This publication honours the memory of my father’s family ancestors and more generally acknowledges the resilience of the Macedonian people, who destined to live, seemingly forever under foreign subjugation, refused to deny their heritage in the face of intense political oppression and on-going cultural discrimination. This account of life and times of a Macedonian villager would not have been possible without the support and well-wishes of members of his family and friends whose own recollections have enriched my father’s narrative. I convey my deepest gratitude for the contributions my father’s brothers, my uncles Sam, Norm and Steve and to his nephew Phillip (dec), who so enthusiastically supported the publication of my father’s story and contributed on behalf of my father’s eldest brother Tom (dec) and his family. -

Same Soil, Different Roots: the Use of Ethno-Specific Narratives During the Homeland War in Croatia

Same Soil, Different Roots: The Use of Ethno-Specific Narratives During the Homeland War in Croatia Una Bobinac A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in International Studies, Russian, Eastern European, Central Asian Studies University of Washington 2015 Committee: James Felak Daniel Chirot Bojan Belić Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies 2 @Copyright 2015 Una Bobinac 3 University of Washington Abstract Same Soil, Different Roots: The Use of Ethno-Specific Narratives During the Homeland War in Croatia Una Bobinac Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Felak History This work looks at the way interpretations and misrepresentations of the history of World War II changed and evolved and their ultimate consequence on the Homeland War in Croatia from 1991 to 1995 between the resident Serb and Croat populations. Explored are the way official narratives were constructed by the communist regime, how and why this narrative was deconstructed, and by more ethno-specific narratives prevailed that fueled the nationalist tendencies of the war. This paper is organized chronologically, beginning with the historical background that puts the rest of the paper into context. The paper also discusses the nationalist resurfacing before the war by examining the Croatian Spring, nationalist re-writings of history, and other matters that influenced the war. The majority of the paper analyzes the way WWII was remembered and dismembered during the late 1980’s and early 1990’s by looking at rhetoric, publications, commemorations, and the role of the Catholic and Serbian Orthodox Churches. Operation Storm, which was the climax of the Homeland War and which expelled 200,000 Serbs serves as an end-point. -

Podujevo-1999-Beyond-Reasonable

Documents Series Podujevo 1999 – Beyond Reasonable Doubt Humanitarian Law Series 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Nataša Kandić: Introduction 5 2. The Organized Crime Department Document 6 3. Record from Interrogation of Saša Cvjetan Before Investigative Judge 9 4. Record from Interrogation of Demirović Dejan Before Investigative Judge. 15 5. Ruling on Cancellation of Investigation and Abolishment of Detention Against Cvjetan and Demirović 22 6. District Public Prosecutor’s Appeal on Ruling to Cancel Interrogation and Abolish Detention 25 7. Serbian Supreme Court’s Ruling on Dismissal of Prokuplje District Court’s Decision 30 8. Investigation in the Prokuplje District Court 37 i) Examination of Witness Dragan Marković 37 ii) Examination of Witness Spasoje Vulević 41 iii) Examination of Witness Zoran Simović 46 iv) District Public Prosecutor’s Indictment 49 9. Proceedings Before Prokuplje District Court 55 i) Saša Cvjetan’s Defence 57 ii) Slobodan Medić’s Testimony 77 10. The HLC Letter Addressed to the Prokuplje Acting District Prosecutor 84 11. The HLC Letter Addressed to the President of the Serbian Supreme Court 86 12. Nataša Kandić: In the Name of the Victims 88 13. Serbian Supreme Court’s Ruling 99 14. Belgrade District Court’s Ruling 101 15. Proceedings Before Belgrade District Court 103 i) Testimony of Miloš Oparnica and Duško Klikovac 103 ii) Identification Record 113 iii) Selatin Bogujevci’s Testimony 123 iv) Testimonies of Saranda Bogujevci and Safet Bogujevci 138 v) Testimonies of Dragan Medić and Slobodan Medić. 154 2 3 vi) Testimonies of Enver Duriqi, Florim Gjata, and Goran Stoparić 161 vi) Testimonies of Rexhep Kastrati and Nazim Veseli 184 16. -

The Kosovo Report

THE KOSOVO REPORT CONFLICT v INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE v LESSONS LEARNED v THE INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON KOSOVO 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford Executive Summary • 1 It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, Address by former President Nelson Mandela • 14 and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Map of Kosovo • 18 Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Introduction • 19 Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw PART I: WHAT HAPPENED? with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Preface • 29 Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the uk and in certain other countries 1. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis • 33 Published in the United States 2. Internal Armed Conflict: February 1998–March 1999 •67 by Oxford University Press Inc., New York 3. International War Supervenes: March 1999–June 1999 • 85 © Oxford University Press 2000 4. Kosovo under United Nations Rule • 99 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) PART II: ANALYSIS First published 2000 5. The Diplomatic Dimension • 131 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, 6. International Law and Humanitarian Intervention • 163 without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, 7. Humanitarian Organizations and the Role of Media • 201 or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation.