Original Article Development of a Reliable and Valid Kata Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premier Karate Course, Leigh Sports Village, 18 Th October 2009

Premier Karate Course, Leigh Sports Village, 18 th October 2009 Mention of the town of Leigh –if it is known at all– suggests images of old Lancashire. Situated to the west of Manchester, coal, Rugby League, cloth caps and cotton are the dominant images. All these motifs remain in the modern Leigh, but in a form that would be far from familiar to the town’s inhabitants from its industrial past. As one approaches the town on the A579, its undulating rollercoaster surface is testament to the subsidence of earlier mining activity. Rugby league continues to wield an important influence, but with a very contemporary feel. The old rugby club has undergone a dramatic facelift in the form of the brown-signed “Sports Village” with modern facilities, not only for the 13-man game, but also for racquet sports, swimming, aerobics and, of course martial arts. My first sight of a flat hat then was not on a middle aged man with a whippet, head bowed against the Lancashire rain. In fact as I pulled into the car park of the Sports Village the dapper figure of 9-time World Karate Champion Wayne Otto, replete with stylish corduroy flat cap, was disembarking from his car. As for cotton, the sight of 150-odd white canvas karategi greeted me as I entered the main sports hall. English National Coach Otto was one of four instructors teaching on the inaugural Premier Karate Seminar. A student of Terry Daly from the Okinawan style of Uechi Ryu, Wayne was joined by three other luminaries, each from a very different style and background. -

Zkušební Řád Trenérsko-Metodické Komise

ČESKÝ SVAZ KARATE Zkušební řád Trenérsko-metodické komise 2017 Platnost od 10. 4. 2017 TECHNICKÁ USTANOVENÍ ( 0 1 / 2 0 1 7 ) VŠEOBECNÁ ČÁST A. Technická část zkušebního řádu určuje rozsah znalostí, vyžadovaných na jednotlivé STV Kyu a DAN. Zkušební komisař je oprávněn prověřit cvičence nejen z vědomostí vyžadovaných na příslušný STV, ale i z náplně kteréhokoliv předcházejícího STV. B. Dále může zkušební komisař upřesnit techniky, aplikace a akce, které umožní komplexně zhodnotit jeho předvedený výkon. Upřesňující techniky, aplikace a akce však musí být v souladu s nároky požadovanými na příslušný STV. Zkoušený musí znát (zpaměti) všechny techniky na dané STV Kyu nebo Dan C. Všeobecný průběh zkoušky STV Kyu a DAN: 1. KIHON: (technika - zkušební komisař náhodně vybere minimálně 1/3 technik) Každou techniku cvičenec vykonává na povel zkušebního komisaře opakovaně za sebou a s maximální koncentrací do doby, než dá zkušební komisař povel na ukončení cvičení. 2. KIHON IDO: (základní techniky v kombinacích - zkušební komisař může vybrat určité kombinace minimálně však 2/3) Každou techniku, resp. kombinaci vykonává cvičenec opakovaně za sebou v jednom směru 5x. Poslední zakončí s KIAI. Po páté technice pokračuje stejnou techniku VZAD 5x do výchozího postavení. (pokud není ve zkušebním řádu jinak např. MAWATE) Takto cvičenec vykoná všechny kombinace technik jdoucí za sebou v daném směru bez zastavení. 3. OYO IDO: (bojové kamae s technikou v kombinacích - zkušební komisař může vybrat kombinace minimálně však 2/3) Každou techniku, resp. kombinaci vykonává cvičenec s KAMAE opakovaně 2 za sebou v jednom směru 5x. Poslední zakončí s KIAI. Po páté technice pokračuje a vykoná MAWATE a pokračuje 5x do výchozího postoje. -

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond

The Folk Dances of Shotokan by Rob Redmond Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States Copyright 2006 Rob Redmond. All Rights Reserved. No part of this may be reproduced for for any purpose, commercial or non-profit, without the express, written permission of the author. Listed with the US Library of Congress US Copyright Office Registration #TXu-1-167-868 Published by digital means by Rob Redmond PO BOX 41 Holly Springs, GA 30142 Second Edition, 2006 2 Kevin Hawley 385 Ramsey Road Yardley, PA 19067 United States In Gratitude The Karate Widow, my beautiful and apparently endlessly patient wife – Lorna. Thanks, Kevin Hawley, for saying, “You’re a writer, so write!” Thanks to the man who opened my eyes to Karate other than Shotokan – Rob Alvelais. Thanks to the wise man who named me 24 Fighting Chickens and listens to me complain – Gerald Bush. Thanks to my training buddy – Bob Greico. Thanks to John Cheetham, for publishing my articles in Shotokan Karate Magazine. Thanks to Mark Groenewold, for support, encouragement, and for taking the forums off my hands. And also thanks to the original Secret Order of the ^v^, without whom this content would never have been compiled: Roberto A. Alvelais, Gerald H. Bush IV, Malcolm Diamond, Lester Ingber, Shawn Jefferson, Peter C. Jensen, Jon Keeling, Michael Lamertz, Sorin Lemnariu, Scott Lippacher, Roshan Mamarvar, David Manise, Rolland Mueller, Chris Parsons, Elmar Schmeisser, Steven K. Shapiro, Bradley Webb, George Weller, and George Winter. And thanks to the fans of 24FC who’ve been reading my work all of these years and for some reason keep coming back. -

Kei Shin Kan Karate-Do Information Booklet KEI SHIN KAN KARATE - DO

Kei Shin Kan Karate-Do Information Booklet KEI SHIN KAN KARATE - DO Background and history Kei Shin Kan Karate-Do is a Japanese form of the martial art of Karate. It arrived in Australia in 1971 and has branches in Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and Tasmania. The founder of Kei Shin Kan is Master Takazawa who was given a dojo by his teacher (Master Toyama) in 1958. Master Takazawa still lives in Nagano Japan. The head of Kei Shin Kan in Australia is Shihan Uchida in Sydney. The benefits of Karate There are many benefits from studying Karate, including : Learn self-defence and how to avoid dangerous situations Improve mental discipline and patience Improve strength, fitness and flexibility Meeting and socialising with a friendly group of students. It is likely to take many years for a normal person to achieve a high standard although students may progress faster depending on their dedication to training. While it is not realistic to set a particular time-frame to achieve black belt level, it is unusual to reach this level in less than 5 years. Again, the speed of progression varies with each individual. The syllabus Much emphasis is placed on learning proper basic techniques including stances, punches and blocks. These movements form the foundation of Karate practice. Sparring is introduced gradually starting with restricted sparring such as one-step sparring. As skills improve other sparring practice is introduced including three-action sparring, hands-only sparring and eventually free sparring. Safety in sparring is paramount. All sparring is strictly non-contact and protective equipment is worn also in case of accidental contact. -

RKV-Info 2009-03

Fachmagazin des Rheinland - Pfälzischen Karateverbandes e.V. 03/2009 DMDM derder JugendJugend && Junioren:Junioren: Kata-GoldKata-Gold fürfür KostantinosKostantinos ThomosThomos EMEM derder StudentenStudenten inin Cordoba:Cordoba: BronzeBronze fürfür KenichiKenichi SatoSato RKV-AusbildungRKV-Ausbildung inin Wittlich:Wittlich: 3131 neueneue C-TrainerC-Trainer Fachverband für Karate im Landessportbund Rheinland-Pfalz e.V. - Mitglied im Deutschen Karate Verband e.V. - Rheinland-Pfälzischer Karateverband e.V. Info 03 2009 IINHALT Geschäftsführendes PRÄSIDIUM Editorial _s. 3 Präsident KADERPORTRAIT: Konstantinos Thomos (Kata) _s. 4 und Stilrichtungreferent Shotokan Gunar Weichert Bericht: RKV-Erfolge beim German-Kata-Cup _s. 5 Eifelstrasse 12, 56727 Mayen Bericht: Luxembourg Open 2009 - _s. 5 Tel.: 02651 / 2669 Fax: 02651 / 541360 E-Mail: [email protected] RKV-Karatejugend international erfolgreich Bericht: RKV-Athleten erfolgreich bei der DM _s. 6 in Bergisch-Gladbach Vizepräsident und Sportreferent Bericht: C-Trainerausbildung in Wittlich 2009 _s. 8 Bernd Otterstätter Marie-Curie-Strasse 1, 67454 Hassloch Bericht: Kenichi Sato belegt den 3.Platz bei der _s. 9 Tel.: 06324 / 82398 Fax: 06324 / 982362 Studenten EM in Cordoba E-Mail: [email protected] Neue Dan-Träger in RKV _s. 9 Bericht: Die vierte Säule des Karate-Do _s. 10 Vizepräsident und Schatzmeister Bericht: „Motivation pur“ - Lehrgang mit _s. 10 Hermann-Josef Andres Marc Stevens in Birkenfeld Stablostrasse 24, 56812 Cochem - Cond Tel.: 02671 / 4513 Fax: 02671 / 4513 Bericht: Bioenergie-Karate in Dahn _s. 11 E-Mail: [email protected] Bericht: Bunkai Jutsu Lehrgang in Traben-Trarbach _s. 12 Bericht: Budokan Kaiserslautern vertreten bei EASI _s. 14 Bericht: Wado-Ryu Prüfungslehrgang in Koblenz _s. 14 Bericht: 8. Sommerlehrgang beim TuS Hirschhorn _s. -

The Development of a Reliable and Valid Kata Performance Analysis Template

Development of a reliable and valid kata performance analysis template Item Type Article Authors Augustovicova, Dusana; Argajova, Jaroslava; Rupcik, Lubos; Thomson, Edward Citation Augustovicova, D., Argajova, J., Rupcik, L., & Thomson, E. (2020). Development of a reliable and valid kata performance analysis template. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 20(6), 3553 - 3559. DOI 10.7752/jpes.2020.06479 Publisher Journal of Physical Education and Sport Journal Journal of Physical Education and Sport Rights Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 29/09/2021 19:42:38 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/624168 The Development of a Reliable and Valid Kata Performance Analysis Template Dusana Augustovicovaa*, Jaroslava Argajovab, Lubos Rupcika and Edward Thomsonc aFaculty of Physical Education and Sports, Comenius University, Bratislava, Slovakia; bSport School Karate, Prievidza, Slovakia; cSport and Exercise Sciences, University of Chester, Chester, United Kingdom *Dušana Augustovicova, Faculty of Physical Education and Sports, Comenius University in Bratislava, Nabrezie armadneho generala Ludvika Svobodu 9, Bratislava 814 69, Slovakia; [email protected] DA and ET designed the study and approved the final manuscript. DA conducted the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DA, JA, LR and ET interpreted the findings and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript. Funding Sources: This study was supported by a Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education of Slovak Republic VEGA No. 1/0654/19. Dusana Augustovicova ORCID 0000-0003-0206-6815 Jaroslava Argajova ORCID 0000-0002-6715-6195 Lubos Rupcik ORCID 0000-0003-2240-0024 Edward Thomson ORCID 0000-0003-4014-9101 The Development of a Reliable and Valid Kata Performance Analysis Template With the new kata evaluation procedure, examination of the underpinning features of successful kata performance appears warranted. -

World Karate Federation

WORLD KARATE FEDERATION Version 6 Amended July 2009 VERSION 6 KOI A MENDED J ULY 2009 CONTENTS KUMITE RULES............................................................................................................................ 3 ARTICLE 1: KUMITE COMPETITION AREA............................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 2: OFFICIAL DRESS .................................................................................................... 4 ARTICLE 3: ORGANISATION OF KUMITE COMPETITIONS ...................................................... 6 ARTICLE 4: THE REFEREE PANEL ............................................................................................. 7 ARTICLE 5: DURATION OF BOUT ............................................................................................ 8 ARTICLE 6: SCORING ............................................................................................................... 8 ARTICLE 7: CRITERIA FOR DECISION..................................................................................... 12 ARTICLE 8: PROHIBITED BEHAVIOUR ................................................................................... 13 ARTICLE 9: PENALTIES........................................................................................................... 16 ARTICLE 10: INJURIES AND ACCIDENTS IN COMPETITION ................................................ 18 ARTICLE 11: OFFICIAL PROTEST ......................................................................................... 19 ARTICLE -

Black Belt History and Terminology STUDY GUIDE for Black Belt Testing

UECHIRYU BUTOKUKAITM Black Belt History and Terminology STUDY GUIDE For Black Belt Testing A Brief History of Uechiryu Karate-Do Uechiryu is purportedly based on three animals: The Tiger, Crane and Dragon The history of Uechiryu (Pronounced Way-Chee -Roo), began in Okinawa on May 5, 1877, with the birth of the founder: Kanbun Uechi. Kanbun was the oldest son of Samurai descendants Kantoku and Tsura Uechi. In 1897, Kanbun left Okinawa for China to avoid a Japanese Military conscription. He arrived in Fuchow City, Fukien Province and began his martial arts training. For the next ten years, he studied under the guidance of a Chinese Monk we know as Shushiwa. In 1907, Shushiwa encouraged Kanbun to open his own school. He eventually did in Nansoe, a day’s journey from Fuchow. Kanbun was credited with being the first Okinawan to operate a school in China. The school ran successfully for three years, then one of his students killed a neighbor in self-defense in a dispute over an irrigation matter. The incident hurt Kanbun to the point that he closed his school and returned to Okinawa. There he married, settled down as a farmer and vowed never to teach again. On June 26th, 1911, his first son Kanei Uechi was born. In 1924 Kanbun Uechi, along with many other Okinawans, left his home and went to Japan for stable employment. He arrived in Wakayama and worked as a janitor. It was here that he met a younger Okinawan Ryuyu Tomoyose. It was through this friendship that Kanbun agreed to begin teaching in a limited capacity. -

The Naihanchi Enigma by Tim Shaw Web Version At

The Naihanchi Enigma by Tim Shaw Web version at: http://www.wadoryu.org.uk/naihanchi.html Introduction Naihanchi kata within Wado Ryu Within the Wado Ryu style of Japanese karate the kata Naihanchi holds a special place, positioned as it is as a gateway to the complexities of Seishan and Chinto. But as a gateway it presents its own mysteries and contradictions. Through Naihanchi Wado stylists are directed to study the subtleties of body movements and develop particular ways of generating energy found primarily in this kata. They are taught that the essence of this ancient Form is to be found in the stance and that the inherent principles are applied directly to the Wado Ryu Kumite (the pairs exercises) and to achieve a stage where these principles become part of the practitioners body and natural movements involves countless repetitions of this particular form. The following tantalizing quote from the founder of Wado Ryu Karate Hironori Ohtsuka, gives intriguing clues as to the value and influence that this particular kata holds. "Every technique (in Naihanchi) has its own purpose. I personally favour Naihanchi. It is not interesting to the eye, but it is extremely difficult to use. Naihanchi increases in difficulty with more time spent practicing it, however, there is something "deep" about it. It is fundamental to any move that requires reaction. Some people may call me foolish for my belief. However, I prefer this kata over all else and hence incorporate it into my movement."1 Many Wado karate-ka practice Naihanchi diligently, while remaining largely unaware of the background and long history of this unusual kata. -

Ryuei-Ryu Karate

Ryuei-ryu Karate - Verfasst von Andreas Reifel - In der Welt des Karate gibt es heute immer noch einige unbekannte Stile und lang versteckte Traditionen. Die deutsche „Karatelandschaft“ kennt meistens Stile wie Shotokan, verschiedene Strömung des Goju-ryu und Shito-ryu, sowie Wado-ryu. Traditionelle Okinawa Stile wie z.B. Uechi-ryu, Kenju-ryu und auch das in diesem Artikel beschriebene Ryuei-ryu Karate sind in Deutschland gänzlich unbekannt. Das Ryuei-ryu Karate war lange Zeit der Öffentlichkeit nicht zugänglich, da seine primären Lehrer bis in die letzten Jahre nur Mitglieder der Nakaima Familie gewesen sind und diese ihre Kunst nicht öffentlich unterrichtet haben. Obwohl gut bekannt mit anderen Karate-Meistern, erwähnt sei hier die Freundschaft von Nakaima Kenko mit Miyagi Chojun, hielt die Nakaima Familie ihr Karate stets im Geheimen. Bis auf sehr spärliche Dokumentation bestehen bis Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts keine schriftlichen Aufzeichnungen über das Ryuei-ryu Karate. Zwischen 1877 und 1880 wurde Ryuei-ryu in Okinawa durch Nakaima Chikudun Pechin Norisato das erste Mal erwähnt. Seinen Ursprung findet das Ryuei, ähnlich dem Naha-Te Higashionnas, in Fuzhou China. Die Bezeichnung Ryuei setzt sich zusammen aus „Ryu“ = von Ryuruko hergeleitet, dem chinesischen Lehrer Nakaimas und „ei“ = einer alternativen Wiedergabe des Namens Nakaima. So ehrt der Stilname sowohl die Familie Nakaima wie auch den chinesischen Meister Ru Ru Ko ( auch Ryu Ru Ko ). Nakaima Norisato (auch Kenri genannt) wurde im Jahre 1850 in Kume (Naha) als Sohn wohlhabender Eltern geboren. Verschiedene Quellen nennen hier auch das Jahr 1819 als sein Geburtsjahr. Früh wurde von Norisato verlangt, die Prinzipien des Bunbu Ryudo zu erlernen. -

Personal Development Student Guide

‘ 北剛柔空⼿道 Karate Studio of Utica Personal Development Student Guide UticaKarate.com Karate Studio of Utica Chief Instructor Profile Kyoshi Shihan Efren Reyes Has well over 30 years of experience practicing and teaching martial arts. He began his Karate training at age 19. No stranger to combative arts since he was already experienced in boxing at the time he was introduced to karate by his older brother. He has groomed and continues to mentor many of our blackbelts both near and far. He holds Kyoshi level certification in Goju-Ryu Karate under the late Sensei Urban and Sensei Van Cliff as well as a 3rd Dan in Aikijutsu under Sensei Van Cliff who has also ranked him master level in Chinese Goju-Ryu. Sensei Urban acknowledged Shihan has the mastery and expertise to be recognized as grand master of his own style of Goju-Ryu since he development of Goju-Ryu had evolved to point of growing his own vision and practice of karate unique to Shihan. This is what is practiced and taught at the Utica Karate. He has also studied Wing Chun in later years to further his understanding and perspective of techniques in close quarters. Shihan has promoted Karate-do through his style of Goju-Ryu under North American Goju karate. Shihan has directed many classes and seminars on various subjects’ ranging from basic self defense to meditation. Karate Studio of Utica Black Belt Instructor Profiles Sensei Philip Rosa Mr. Rosa holds the rank of Sensei (5th degree) and has been practicing Goju-Ryu Karate under Shihan Reyes since 1990. -

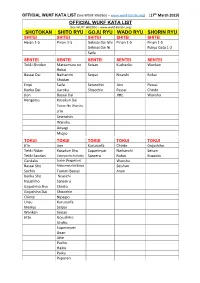

Official Wukf Kata List Shotokan Shito Ryu Goju

OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) [17th March 2019] OFFICIAL WUKF KATA LIST (See WUKF WebSite – www.wukf-Karate.org) SHOTOKAN SHITO RYU GOJU RYU WADO RYU SHORIN RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Heian 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ichi Pinan 1-5 Pinan 1-5 Gekisai Dai Ni Fukyu Gata 1-2 Saifa SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Tekki Shodan Matsumura no Seisan Kushanku Wankan Rohai Bassai Dai Naihanchi Seipai Niseishi Rohai Shodan Empi Saifa Seiunchin Jion Passai Kanku Dai Jiuroku Shisochin Passai Chinto Jion Bassai Dai Jitte Wanshu Hangetsu Kosokun Dai Tomari No Wanshu Ji'in Seienchin Wanshu Aoyagi Miojio TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI TOKUI Ji'in Jion Kururunfa Chinto Gojushiho Tekki Nidan Kosokun Sho Suparimpai Naihanchi Seisan Tekki Sandan Ciatanyara No Kushanku Sanseru Rohai Kusanku Gankaku Sochin (Aragaki ha) Wanshu Bassai Sho Matsumura No Bassai Seishan Sochin Tomari Bassai Anan Kanku Sho Niseichi Nijushiho Sanseiru Gojushiho Sho Chinto Gojushiho Dai Shisochin Chinte Nipaipo Unsu Kururunfa Meikyo Seipai Wankan Seisan Jitte Gojushiho Unshu Suparimpei Anan Jitte Pacho Haiku Paiku Papuren KATA LIST - WUKF COMPETITION UECHI RYU KYOKUSHINKAI BUDOKAN GOSOKU RYU SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI SHITEI Kanshiva Pinan 1-5 Heian 1-5 Kihon Ichi No Kata Sechin Kihon Yon No Kata Kanshu Kime Ni No Kata Seiryu (Kiyohide) Ryu No Kata Uke No Kata SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI SENTEI Sesan Geksai Dai Empi Ni No Kata Kanchin Tsuki No Kata Tekki 1-2 Kime No Kata Sanseryu Yantsu Bassai Dai Gosoku Tensho Kanku Dai Gosoku Yondan Saifa Jion Sanchin no