Exotic and Hypothetical Species 593

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

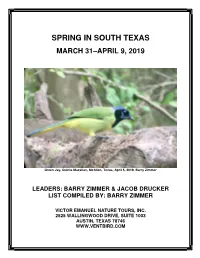

Spring in South Texas

SPRING IN SOUTH TEXAS MARCH 31–APRIL 9, 2019 Green Jay, Quinta Mazatlan, McAllen, Texas, April 5, 2019, Barry Zimmer LEADERS: BARRY ZIMMER & JACOB DRUCKER LIST COMPILED BY: BARRY ZIMMER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SPRING IN SOUTH TEXAS MARCH 31–APRIL 9, 2019 By Barry Zimmer Once again, our Spring in South Texas tour had it all—virtually every South Texas specialty, wintering Whooping Cranes, plentiful migrants (both passerine and non- passerine), and rarities on several fronts. Our tour began with a brief outing to Tule Lake in north Corpus Christi prior to our first dinner. Almost immediately, we were met with a dozen or so Scissor-tailed Flycatchers lining a fence en route—what a welcoming party! Roseate Spoonbill, Crested Caracara, a very cooperative Long-billed Thrasher, and a group of close Cave Swallows rounded out the highlights. Strong north winds and unsettled weather throughout that day led us to believe that we might be in for big things ahead. The following day was indeed eventful. Although we had no big fallout in terms of numbers of individuals, the variety was excellent. Scouring migrant traps, bays, estuaries, coastal dunes, and other habitats, we tallied an astounding 133 species for the day. A dozen species of warblers included a stunningly yellow male Prothonotary, a very rare Prairie that foraged literally at our feet, two Yellow-throateds at arm’s-length, four Hooded Warblers, and 15 Northern Parulas among others. Tired of fighting headwinds, these birds barely acknowledged our presence, allowing unsurpassed studies. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Thailand Highlights 14Th to 26Th November 2019 (13 Days)

Thailand Highlights 14th to 26th November 2019 (13 days) Trip Report Siamese Fireback by Forrest Rowland Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Forrest Rowland Trip Report – RBL Thailand - Highlights 2019 2 Tour Summary Thailand has been known as a top tourist destination for quite some time. Foreigners and Ex-pats flock there for the beautiful scenery, great infrastructure, and delicious cuisine among other cultural aspects. For birders, it has recently caught up to big names like Borneo and Malaysia, in terms of respect for the avian delights it holds for visitors. Our twelve-day Highlights Tour to Thailand set out to sample a bit of the best of every major habitat type in the country, with a slight focus on the lush montane forests that hold most of the country’s specialty bird species. The tour began in Bangkok, a bustling metropolis of winding narrow roads, flyovers, towering apartment buildings, and seemingly endless people. Despite the density and throng of humanity, many of the participants on the tour were able to enjoy a Crested Goshawk flight by Forrest Rowland lovely day’s visit to the Grand Palace and historic center of Bangkok, including a fun boat ride passing by several temples. A few early arrivals also had time to bird some of the urban park settings, even picking up a species or two we did not see on the Main Tour. For most, the tour began in earnest on November 15th, with our day tour of the salt pans, mudflats, wetlands, and mangroves of the famed Pak Thale Shore bird Project, and Laem Phak Bia mangroves. -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Bird Damage to Pistachios

The extent of damage to pistachios by some birds that knock nuts to the ground, where they hull, shell, and eat them, can be measured. Losses to birds that pluck nuts from the tree and fly off to eat them else- where can only be estimated. counties to the south. District I1 (Central) is Merced, Madera, Fresno, and Kings Bird damage to nistachios counties. District I11 (Northern) is Monte- rey, San Benito, Inyo, and all counties to the north of Merced County. Terrell P. Salmon 0 A. Charles Crabb 0 RexE.Marsh Scope of the problem We received 105 responses (23 percent) from the 458 surveys mailed. Thirteen (12.7 percent) were excluded from analy- Crows are the primary culprits sis, because the orchards represented followed by ravens and jays were not in production, were outside Cali- fornia, or were managed by another per- son. The remaining 92 indicated they had pistachio losses due to one or more bird species. Bird damage was widespread through- out the state, as indicated by surveys re- turned from 18 counties. These 18 coun- ties represent 98 percent of the bearing pistachio acreage in California. The infor- mation we report here is based on the sur- vey returns and does not account for bird Various bird species are pests to a step in defining the problem and evaluat- damage and control that undoubtedly oc- number of California crops. Nut crops ing current bird control methods. cur but were not reported. Our estimates such as pistachios, almonds, and walnuts The major focus of the survey was to should therefore be considered conserva- are particularly hard hit, although infor- identify the bird species involved, the ex- tive. -

Pica (Pica) Bottanensis in India

PRŷS-JONES & RASMUSSEN: Black-rumped Magpie 71 The status of the Black-rumped Magpie Pica (pica) bottanensis in India Robert P. Prŷs-Jones & Pamela C. Rasmussen Prŷs-Jones, R. P., & Rasmussen, P. C., 2018. The status of the Black-rumped Magpie Pica (pica) bottanensis in India. Indian BIRDS 14 (3): 71–73. Robert P. Prŷs-Jones, Bird Group, Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, Akeman St, Tring, Herts HP23 6AP, UK. E-mail: [email protected] [RPP-J] Pamela C. Rasmussen, Department of Integrative Biology and MSU Museum, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48864, USA; Bird Group, Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, Akeman St, Tring, Herts HP23 6AP, UK. E-mail: [email protected] [PCR] Manuscript received on 01 February 2018. he presence of the Eurasian Magpie Pica pica (sensu lato) in India (Praveen within Native Sikkim, any such records having et al. 2016) is predominantly based on the well-documented occurrence of more probably been a mistake for southern Tthe race bactriana in the north-western Himalayas east to northern Himachal Tibet,” (Meinertzhagen 1927: 371). There is Pradesh (Rasmussen & Anderton 2012; Dickinson & Christidis 2014). However, thus a clear contradiction between his own the question as to whether the taxon bottanensis may additionally occur, or have writings and the existence of his specimen, occurred, in Sikkim has recently resurfaced as a result of a comprehensive molecular from which we deduce that he most likely phylogenetic study of the genus Pica by Song et al. (2018), who recognised Pica (p.) stole the specimen later, relabelling it without bottanensis to be an anciently diverged and distinctive lineage. -

Cryptic Speciation Among Meiofaunal Flatworms Henry J

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 8-2018 Cryptic Speciation Among Meiofaunal Flatworms Henry J. Horacek Winthrop University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Horacek, Henry J., "Cryptic Speciation Among Meiofaunal Flatworms" (2018). Graduate Theses. 94. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/94 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRYPTIC SPECIATION AMONG MEIOFAUNAL FLATWORMS A thesis Presented to the Faculty Of the College of Arts and Sciences In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Science In Biology Winthrop University August, 2018 By Henry Joseph Horacek August 2018 To the Dean of the Graduate School: We are submitting a thesis written by Henry Joseph Horacek entitled Cryptic Speciation among Meiofaunal Flatworms. We recommend acceptance in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biology __________________________ Dr. Julian Smith, Thesis Advisor __________________________ Dr. Cynthia Tant, Committee Member _________________________ Dr. Dwight Dimaculangan, Committee Member ___________________________ Dr. Adrienne McCormick, Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences __________________________ Jack E. DeRochi, Dean, Graduate School Table of Contents List of Figures p. iii List of Tables p. iv Abstract p. 1 Acknowledgements p. 2 Introduction p. 3 Materials and Methods p. 18 Results p. 28 Discussion p. -

Class Three: Breeding

Class Three: Breeding WHERE DO SEABIRDS LAY THEIR EGGS? Nest or no nest? • Some species use no nesting material. E.g., the white tern lays a single egg on an open branch. • Some species use a very little bit of nesting material. E.g., the tufted puffin may use a few pieces of grass and a couple of feathers. • Some species build more substantial nests. E.g. kittiwakes cement their nests onto small cliff shelves by trampling mud and guano to form a base. And, some cormorants build large nests in trees from sticks and twigs. [email protected] www.seabirdyouth.org 1 White tern • Also called fairy tern. • Tropical seabird species. • Lays egg on branch or fork in tree. No nest. • Newly hatched chicks have well developed feet to hang onto the nesting-site. White Tern. © Pillot, via Creative Commons. On the coast or inland? • Most seabird species breed on the coast and offshore islands. • Some species breed fairly far inland, but still commute to the ocean to feed. E.g., kittlitz’s murrelets nest on scree slopes on coastal mountains, and parents may travel more than 70km to their feeding grounds. • Other species breed far inland and never travel to the ocean. E.g., double crested cormorants breed on the coast, but also on lakes in many states such as Minnesota. [email protected] www.seabirdyouth.org 2 NESTING HABITAT (1) Ground Some species breed on the ground. These species tend to breed in areas with little or no predation, such as offshore islands (e.g., terns and gulls) or in the Antarctic (e.g., penguins, albatross). -

Fricke Washington 0250E 14267.Pdf (3.107Mb)

Benefits of seed dispersal for plant populations and species diversity Evan Fricke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Joshua Tewksbury Janneke Hille Ris Lambers Jeffrey Riffell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Biology 1 ©Copyright 2015 Evan Fricke 2 University of Washington Abstract Benefits of seed dispersal for plant populations and species diversity Evan Fricke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Joshua Tewksbury Department of Biology Seed dispersal influences plant diversity and distribution, and animals are the major vector of dispersal in the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems. Defaunation occurring at the global scale threatens a pervasive disruption of seed dispersal mutualisms. Understanding the scope of this problem and developing predictions for the impact of seed disperser loss on plant diversity requires knowledge of the ways in which dispersers benefit their plant mutualists and how the loss of these benefits influence plant population dynamics. The first chapter explores novel benefits of seed dispersal in a wild chili from Bolivia caused by the reduction of antagonistic species interactions via gut-passage by avian frugivores. The second chapter measures how movement away from parent plants influences species interactions for three tree species in the Mariana Islands, assessing the source of distance-dependent mortality. The third chapter quantifies demographic impacts of density-dependent mortality in the forest at Barro Colorado Island, Panamá. The last chapter uses network concepts and information of the benefits of mutualisms to improve coextinction predictions within plant-animal mutualistic networks. 3 Table of Contents Chapter 1: When condition trumps location: seed consumption by fruit-eating birds removes pathogens and predator attractants ……………………………………………. -

Birds & Butterflies of South Texas and the Rio Grande Valley

Birds & Butterflies of South Texas and the Rio Grande Valley Naturetrek Tour Itinerary Outline itinerary Day 1 Fly Austin, Texas & overnight Day 2/3 Knolle Farm Ranch, Aransas and Corpus Christi Day 4/6 Chachalaca, lower Rio Grande Valley Day 7/9 The Alamo Inn, middle Rio Grande Valley Day 10 Knolle Farm Ranch Day 11 Choke Canyon State Park & San Antonio Day 12/13 Depart Austin / arrive London Departs November Focus Birds, butterflies, some mammals and reptiles Grading A. Easy walking Dates and Prices See www.naturetrek.co.uk (tour code USA15) or the current Naturetrek brochure Highlights • Relaxed pace of birding and butterfly-watching • Stay in famous ‘birding inns’ • Over 300 species of butterfly recorded • Whooping Cranes at Aransas Wildlife Refuge • Rio Grande specialities such as Green Jay and From top: Green Jay, Queen, Whooping Crane (images by Jane Dixon Altamira Oriole, plus other rarities and migrants and Adam Dudley) Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Birds & Butterflies of South Texas and the Rio Grande Valley Tour Itinerary Introduction The lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas is one of the most exciting areas in North America for birds and butterflies. From Falcon Dam in the north to South Padre Island on the coast, this region is famous among naturalists as the key place to see an exciting range of wildlife found nowhere else in the United States. Subtropical habitats along the lower Rio Grande Valley form an extension of Mexico’s 'Tamaulipan Biotic Province', home to species characteristic of north-eastern Mexico, and an explosion of butterfly gardens throughout the valley has resulted in more species of butterfly being recorded here than in any other region of the country. -

India: Kaziranga National Park Extension

INDIA: KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION FEBRUARY 22–27, 2019 The true star of this extension was the Indian One-horned Rhinoceros (Photo M. Valkenburg) LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM INDIA: KAZIRANGA NATIONAL PARK EXTENSION February 22–27, 2019 By Machiel Valkenburg This wonderful Kaziranga extension was part of our amazing Maharajas’ Express train trip, starting in Mumbai and finishing in Delhi. We flew from Delhi to Guwahati, located in the far northeast of India. A long drive later through the hectic traffic of this enjoyable country, we arrived at our lodge in the evening. (Photo by tour participant Robert Warren) We enjoyed three full days of the wildlife and avifauna spectacles of the famous Kaziranga National Park. This park is one of the last easily accessible places to find the endangered Indian One-horned Rhinoceros together with a healthy population of Asian Elephant and Asiatic Wild Buffalo. We saw plenty individuals of all species; the rhino especially made an impression on all of us. It is such an impressive piece of evolution, a serious armored “tank”! On two mornings we loved the elephant rides provided by the park; on the back of these attractive animals we came very close to the rhinos. The fertile flood plains of the park consist of alluvial silts, exposed sandbars, and riverine flood-formed lakes called Beels. This open habitat is not only good for mammals but definitely a true gem for some great birds. Interesting but common birds included Bar-headed Goose, Red Junglefowl, Woolly-necked Stork, and Lesser Adjutant, while the endangered Greater Adjutant and Black-necked Stork were good hits in the stork section.