Saskatchewan Prosperity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canwest Top 100 Saskatchewan Companies

Wednesday, September 30, 2009 Saskatoon, Saskatchewan TheStarPhoenix.com D1 New Top 100 list showcases Sask.’s diversification By Katie Boyce almost $3 billion since 2007. Viterra Inc., in its second year of his year’s Top 100 Saskatchewan operation, has also experienced significant Companies list is filled with sur- growth in revenue, jumping by almost T prises. $3 billion in the last year to claim third Besides a new company in the No. 1 spot, ranking. Long-standing leaders Canpotex 23 businesses are featured for the first time Limited and Cameco Corporation continue in the 2009 ranking, which is based on 2008 to make the top five, backed by the profit- gross revenues and sales. The additions able potash market. — headquartered in Carlyle, Davidson, Este- One major modification to this year’s list van, Lampman, Melfort, Regina, Rosetown, has been to exclude the province’s individual Saskatoon, Warman, and Yorkton — show retail co-operatives, instead allowing Feder- off the incredible economic growth that our ated Co-operatives Ltd. to represent these province has experienced during the last year. businesses. Another change has been in how 1 Covering a wide cross-section of industries SaskEnergy reports its revenue. Rather than in our province, newcomers to the list include providing gross revenue amounts, the crown PotashCorp Allan Construction, Kelsey Group of Compa- corporation started this fiscal year to report nies, Partner Technologies Incorporated and only net revenue, which accounts for the Reho Holding Ltd. (owner of several Warman significant drop in rankings. companies) in the manufacturing and con- The Top 100 Saskatchewan Companies is struction field, and Arch Transco Ltd. -

2015-2016 Annual Report

2015-2016 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Association Profile………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 01 Our Vision………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 01 Our Mission………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 01 Strategic Priorities (2015-2016)…………………………………………………………………………………………..01 ACEC-SK Code of Consulting Practice……………………………………………………………………………….………….....02 2015-2016 ACEC-SK Board of Directors………………………………………………………………...…………….…………03 Chair’s Report…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....04 Executive Director’s Report……………………………………………………………………………...…………………………....06 2014 – 2015 ACEC-SK Annual General Meeting Minutes………………………………………………………………….08 Buildings (Regina & Saskatoon) Committee Report..………………………………………………………………………..14 Communications Committee Report……………………………………………………………………………...………………..15 Environment/Water Resources Committee Report…………………………………………………………………………..16 Human Resources Committee Report………………………………………………………………………………………………17 Industry/Resources Committee Report……………………………………………………………………………………………19 Risk Mitigation Committee Report……………………………………………………………………………………….…….…….21 Transportation Committee Report…………………………………………………………………..….……………………………22 ACEC-Canada Liaison Report……………………………………………………………………………………………………………23 Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists (APEGS) Liaison Report………………………………25 Women in Consulting Committee Report………………………………………………………………………………………….27 Young Professionals Group Liaison Report…………………………………………………….…………………….…………....28 Associate Member -

Saskatchewan Provincial Budget 2012-13 Budget Summary

The Honourable Ken Krawetz Deputy Premier Minister of Finance SASKATCHEWAN PROVINCIAL BUDGET 12-13 KEEPING THE SASKATCHEWAN ADVANTAGE BUDGET SUMMARY MiniSter’S MeSSage I’m pleased to table the 2012-13 Budget and supporting documents for public discussion and review. Over the past few years, Saskatchewan people have helped to create the “Saskatchewan Advantage,” a combination of balanced budgets, reduced debt and lower taxes, a strong and growing economy and the tremendous quality of life we all enjoy. Our province is now the best place in Canada to live, work, start a business, receive an education, raise a family and build a life. Saskatchewan has become a magnet for people across the country and around the world, recording the largest population growth in any census period since Statistics Canada started doing the census every five years in 1956. People are coming here because they recognize that Saskatchewan is now a place of opportunity. Keeping the SaSKatchewan advantage The 2012-13 Budget is all about “Keeping the Saskatchewan Advantage.” While other jurisdictions post deficits, Saskatchewan will once again balance its budget. While other provinces struggle with sluggish growth, Saskatchewan is projected to lead the nation in economic growth. Even in a time of global uncertainty, our government’s focus will remain squarely on enhancing and preserving Saskatchewan’s quality of life through prudent fiscal management. This year’s budget also strives to make life more affordable and provide better access to health care. This budget provides for enhancements to the Active Families Benefit, as well as for the introduction of a Saskatchewan Advantage scholarship and a Saskatchewan Advantage grant for education savings. -

A New Vision for Saskatchewan's Economy

______________________________________________________________________________ Why Change? Saskatchewan has epitomized great promise and potential since its creation through an Act of Parliament 100 years ago. It is the country’s second largest producer of oil and the third largest producer of natural gas. Saskatchewan is home to a third of the world’s supply of potash, a third of the world’s supply of uranium and the most arable acres in the Dominion. We are well positioned for success in the new knowledge-based economy thanks to Canada’s only synchrotron and leading-edge research parks at the province’s two universities. Saskatchewan’s wealth in human and natural resources is truly staggering. Given our potential, Saskatchewan should have finished the 20th century as one of Canada’s economic leaders – ready to compete in the emerging global economy. Instead, our province entered this century after having spent most of the last century as a ‘have-not’ province. The statistics are startling. Between 1981 and 2000, total employment in Saskatchewan grew by only 12.5% compared to 34% in Alberta and 32% across Canada. Only Newfoundland posted a worse job creation record than Saskatchewan during these two decades. Over the same period, Saskatchewan’s economy grew by 60%. While that was more than Manitoba, it was less than the national average and half the GDP growth experienced by Alberta. The lack of meaningful growth in personal disposable income and per capita income is another indication of how far Saskatchewan has fallen behind. Between 1981 and 2000, real disposable income in Saskatchewan increased by only 7.6% -- well behind the rest of Canada (36.8%), Alberta (34.6%) and Manitoba (18.8%).1 In 1974, Saskatchewan per capita personal income was 102% of the Canadian average. -

Saskatchewan's Growth Plan

VISION 2020 AND BEYOND Opening Message Too often enterprise-oriented governments appear to seek growth for the sake of growth. This is a mistake – one that can cause governments to lose focus and discipline. The Saskatchewan Plan for Growth is about that focus and discipline. It sets out the Government of Saskatchewan’s vision for a province of 1.2 million people by 2020. It is a plan for economic growth that builds on the strength of Saskatchewan’s people, resources and innovation to sustain Saskatchewan’s place among Canada’s economic leaders. Growth will be a result of continued investments in a competitive economy, infrastructure and a skilled workforce. Building on our agricultural and natural resource advantage, Saskatchewan will be a global leader in export and trade by 2020 and will invest in knowledge and innovation in the development of Saskatchewan’s future economy. Capital investments in new projects and expansions will grow our economy, and Saskatchewan will continue to welcome newcomers from across Canada and throughout the world to live and work in our province. An expanding economy is the foundation for a growing and prosperous province. The purpose of growth is to build a better quality of life for all Saskatchewan residents. To this end, the Saskatchewan Plan for Growth outlines the government’s direction to improve health care and education outcomes, while building growing and safe communities and improving the lives of persons with disabilities in Saskatchewan. The Saskatchewan Plan for Growth reaffirms the provincial government’s commitment to fiscal responsibility through balanced budgets and further reduction in government debt. -

Budget and Performance Plan Summary Minister of Finance Minister’S Message

2004 –2005 Saskatchewan Provincial Budget The Hon. Harry Van Mulligen Budget and Performance Plan Summary Minister of Finance Minister’s Message I am pleased to table the 2004-05 Budget and supporting documents for public review and discussion. This document provides more than just budget numbers. It includes comprehensive reports on both our fiscal and economic outlook, which forms the context and foundation for the 2004-05 Budget. I would like to point out two sections that are particularly relevant in this year’s Budget. First, a technical paper that discusses federal transfers, one of our most challenging issues. Secondly, a section that examines health care funding. Health care represents our most rapidly growing expenditure area. This section of the report outlines how this money is being spent and the ongoing funding needs required to maintain the current health system. I also encourage you to review the government-wide performance plan summary that sets out the broad vision and goals for government departments. Individual plans, with detailed goals and objectives, are also available on each department’s website. These performance plans are one further step in our ongoing commitment to improving accountability of this Government to the people of Saskatchewan. It is my hope that the material found in these documents will help create a solid understanding of our economy, our finances, and Saskatchewan’s future. Harry Van Mulligen Minister of Finance Table of Contents INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW Performance Plan Summary . 4 TECHNICAL PAPERS Health Care Spending in Saskatchewan . 20 Equalization . 26 Saskatchewan’s Economic Outlook . 32 Saskatchewan’s GRF Financial Outlook . -

Ccall Regina Elphinstone-Centre

STANDING COMMITTEE ON CROWN AND CENTRAL AGENCIES Hansard Verbatim Report No. 25 – October 6, 2005 Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan Twenty-fifth Legislature STANDING COMMITTEE ON CROWN AND CENTRAL AGENCIES 2005 Mr. Graham Addley, Chair Saskatoon Sutherland Mr. Dan D’Autremont, Deputy Chair Cannington Ms. Doreen Eagles Estevan Mr. Andy Iwanchuk Saskatoon Fairview Mr. Allan Kerpan Carrot River Valley Mr. Warren McCall Regina Elphinstone-Centre Hon. Mark Wartman Regina Qu’Appelle Valley Published under the authority of The Honourable P. Myron Kowalsky, Speaker STANDING COMMITTEE ON CROWN AND CENTRAL AGENCIES 493 October 6, 2005 [The committee met at 10:00.] with legislation governing its activities related to financial reporting, safeguarding public resources, revenue raising, The Chair: — Good morning and I’ll call to order the Standing spending, borrowing, and investing. Therefore we have no Committee on Crown and Central Agencies. Some recommendations on these matters that require the attention of administrative issues, just to remind members that the this committee. committee meeting is being webcast and is available for in-house TV viewing. Following today’s meeting, the full In carrying out our work we worked together with the appointed meeting will be video streamed on the Internet and will be on auditors, Meyers Norris Penny, and we received excellent the Legislative Assembly committee website. And the co-operation from both Meyers Norris Penny and also the television rebroadcast for the public will occur in November, management of SaskWater. and I’m sure we’ll all be waiting for that. Mr. Drayton: — Thank you, Mr. Chair. My comments would Today’s agenda is reviewing the SaskWater 2004 annual report also be brief. -

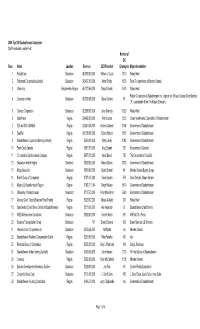

2009 Top 100 List

2009 Top 100 Saskatchewan Companies StarPhoenix and Leader-Post Number of SK Rank Name Location Revenue CEO/President Employees Major shareholders 1 PotashCorp Saskatoon $9,898,000,000 William J. Doyle 1810 Widely Held 2 Federated Co-operatives Limited Saskatoon $8,400,368,000 Arthur Postle 1500 Retail Co-operatives in Western Canada 3 Viterra Inc. Registered in Regina $6,777,566,000 Mayo Schmidt 1600 Widely Held Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan Inc., Agrium Inc., Mosaic Canada Crop Nutrition, 4Canpotex Limited Saskatoon $5,200,000,000 Steve Dechka 63 LP., a subsidiary of the The Mosaic Company 5 Cameco Corporation Saskatoon $2,859,000,000 Jerry Grandey 1820 Widely Held 6 SaskPower Regina $1,489,000,000 Pat Youzwa 2500 Crown Investments Corporation of Saskatchewan 7 SGI and SGI CANADA Regina $1,241,684,000 Andrew Cartmell 1894 Government of Saskatchewan 8 SaskTel Regina $1,138,000,000 Robert Watson 5063 Government of Saskatchewan 9 Saskatchewan Liquor and Gaming Authority Regina $960,980,000 Barry Lacey 1085 Government of Saskatchewan 10 Farm Credit Canada Regina $951,700,000 Greg Stewart 760 Government of Canada 11 Co-operators Life Insurance Company Regina $857,700,000 Kevin Daniel 720 The Co-operators Group Ltd. 12 Saskatoon Health Region Saskatoon $808,000,000 Maura Davies 12000 Government of Saskatchewan 13 Mega Group Inc. Saskatoon $800,000,000 Benoit Simard 48 Member Owned Buying Group 14 Brandt Group of Companies Regina $797,467,000 Gavin Semple 575 Gavin Semple, Shaun Semple 15 Regina Qu'Appelle Health Region Regina $742,717,194 Dwight Nelson 9500 Government of Saskatchewan 16 University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon $710,572,000 Peter MacKinnon 6923 Government of Saskatchewan 17 Alliance Grain Traders/Saskcan Pulse Trading Regina $328,672,293 Murad Al-Katib 240 Widely Held 18 SaskCentral (Credit Union Central of Saskatchewan) Regina $317,860,000 Ken Anderson 97 Saskatchewan Credit Unions 19 AREVA Resources Canada Inc. -

2018/19 | Message to Our Stakeholders Message to Our Stakeholders

Special thanks to the Innovation Place tenants who shared photos for use in the Annual Report. Letter OF Transmittal June 1, 2019 To His Honour The Honourable W. Thomas Molloy, OC SOM QC Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan Dear Sir: I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of Saskatchewan Opportunities Corporation for the 12 month period ended March 31, 2019, including the financial statements duly certified in accordance with The Saskatchewan Opportunities Corporation Act. Respectfully submitted, Joe Hargrave Minister Responsible for Saskatchewan Opportunities Corporation Table of Contents 1 Message to Our Stakeholders 6 Our Strategy 8 Our Business 17 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 40 Corporate Governance 54 Management’s Responsibility and Certification 56 Independent Auditors’ Report 59 Financial Report Annual Report 2018/19 | Message to Our Stakeholders Message to Our Stakeholders From Board Chair, Mark Regier, and President & CEO, Van Isman Over the last several years, our Message to Our Stakeholders has revolved around providing an update on the progress we have made in achieving our strategic plan. Typically, these messages have focused on the outputs of our efforts. Last year our message focused on more of the outcomes of our efforts – a dozen thriving and successful technology businesses that originated at Innovation Place. In keeping with our tagline of Innovation Place is Helping Grow Saskatchewan’s Tech Sector, we continue to feature a number of our successful tenants in this year’s annual report, but this Message to Our Stakeholders is taking a different direction this year. This year we are focusing on inputs, primarily on what distinguishes Innovation Place from other spaces and locations. -

2003-04 Budget Summary

2003 - 04 SASKATCHEWAN Provincial Budget BUILDING FOR THE FUTURE Budget Summary SASKATCHEWAN The Hon. Jim Melenchuk Minister of Finance Table of Contents Introduction and Overview Building for the Future . 2 Technical Papers General Revenue Fund 2003-04 . .16 Saskatchewan’s Economic Outlook . 19 Saskatchewan’s Financial Outlook . .25 2003-04 Revenue Initiatives . 29 Income Tax Revenue . 32 Saskatchewan’s Tax Expenditures . .34 2003 Intercity Comparison of Taxes and Household Charges . 39 Major Federal Transfers . 44 2003-04 Borrowing and Debt . 47 Oil Revenue . 54 Fiscal Stabilization Fund . 56 Four-Year Financial Plan . 57 Budget Details (financial tables) GRF – Statement of Revenue, Expenditure and Accumulated Deficit . 60 GRF – Statement of Cash Flow . 61 GRF – Schedule of Revenue . 62 GRF – Schedule of Expenditure . .63 GRF – Schedule of Borrowing Requirements . 64 GRF – Schedule of Debt . 65 GRF – Schedule of Guaranteed Debt . 66 1 Building for the Future A Plan Last year’s Budget (2002-03) was balanced without a transfer from the Fiscal Stabilization Fund; in “Building for the Future” is a vision, a plan, the fact, a $2.1 million surplus is forecast for the year. Government has for Saskatchewan. The Fund has served its purpose well, allowing the Province to draw on it when required, using Building for the future is about building discretion and financial prudence. It has proven to momentum – for growth and opportunity – and be a sound financial tool for the Government. building programs and support for Saskatchewan Budget 2003-04 estimates a $393 million transfer people. Building for the future means having: from the Fund – to help meet the needs and • Healthy and Self-Reliant Families priorities of Saskatchewan people. -

Form 18-K Securities and Exchange Commission

FORM 18-K For Foreign Governments and Political Subdivisions Thereof SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. ANNUAL REPORT of PROVINCE OF SASKATCHEWAN CANADA (Name of Registrant) Date of end of last fiscal year: March 31, 2013 SECURITIES REGISTERED* (As of close of fiscal year) Amounts as to Names of Title of issue which registration exchanges on is effective which registered N/A N/A N/A *The Registrant is filing this annual report on a voluntary basis. Names and addresses of persons authorized to receive notices and communications from the Securities and Exchange Commission: JOHN PRATO Canadian Consul General Canadian Consulate 1251 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 or DONALD WILSON Canadian Consulate 1251 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 Copies to: CLARE ISMAN JOHN W. WHITE Deputy Minister of Finance Cravath, Swaine & Moore Ministry of Finance Worldwide Plaza Province of Saskatchewan 825 Eighth Avenue 2350 Albert Street New York, N.Y. 10019 Regina, Saskatchewan Canada S4P 4A6 2 The information set forth below is to be furnished: 1. In respect of each issue of securities of the registrant registered, a brief statement as to: (a) The general effect of any material modifications, not previously reported, of the rights of the holders of such securities. None. (b) The title and the material provisions of any law, decree or administrative action, not previously reported, by reason of which the security is not being serviced in accordance with the terms thereof. None. (c) The circumstances of any other failure, not previously reported, to pay principal, interest, or any sinking fund or amortization instalment. -

Notice of Annual General Meeting of Shareholders of Information Services Corporation to Be Held on May 16, 2018 and Management Information Circular

Notice of Annual General Meeting of Shareholders of Information Services Corporation to be held on May 16, 2018 and Management Information Circular April 10, 2018 company.isc.ca TSX:ISV Contents Page Letter to Shareholders 3 Notice of Annual General Meeting 4 Management Information Circular 5 About the Meeting 5 Who Can Vote 6 How to Vote 6 Principal Owners of Class A Shares 10 Business of the Meeting 11 Consolidated Financial Statements 11 Electing Our Directors 11 Appointing Our Auditor 20 Corporate Governance and Board Committees 21 Director Compensation 25 Compensation Discussion and Analysis 28 Employee Agreements, Termination and Change of Control Benefits 42 Securities Authorized for Issuance Under Equity Compensation Plans 44 Stock Option Plan 44 Additional Information 47 2 ISC® MANAGEMENT INFORMATION CIRCULAR 2018 April 10, 2018 Dear Shareholder: We are pleased to invite you to the annual general meeting of shareholders of Information Services Corporation (“ISC”), which will be held at 9:00 a.m. (Saskatchewan time/MDT) on May 16, 2018, at Innovation Place, 6 Research Drive, Regina, Saskatchewan. The annual general meeting is an opportunity to consider matters of importance to ISC and shareholders. We look forward to your participation in person or by proxy at the meeting. You are encouraged to read the accompanying Management Information Circular in advance of the meeting, which describes the business to be conducted at the meeting and provides information on ISC’s approach to executive compensation and governance practices. If you are unable to attend the meeting in person, you can vote by telephone, online or by completing and returning the enclosed proxy.