Portraiture, Authorship, and the Authentication of Shakespeare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gay Marriage Opponents Closer To

Columbia Foundation Articles and Reports July 2012 Arts and Culture ALONZO KING’S LINES BALLET $40,000 awarded in August 2010 for two new world-premiere ballets, a collaboration with architect Christopher Haas (Triangle of the Squinches) and a new work set to Sephardic music (Resin) 1. Isadora Duncan Dance Awards, March 27, 2012 2012 Isadora Duncan Dance Award Winners Announced Christopher Haas wins a 2012 Isadora Duncan Dance Award for Outstanding Achievement in Visual Design for his set design for Triangle of the Squinches. Alonzo King’s LINES Ballet wins two other Isadora Duncan Dance Awards for the production Sheherazade. ASIAN ART MUSEUM $255,000 awarded since 2003, including $50,000 in July 2011 for Phantoms of Asia, the first major exhibition of Asian contemporary art from May 18 to September 2, 2012, which explores the question “What is Asia?” through the lens of supernatural, non-material, and spiritual sensibilities in art of the Asian region 2. San Francisco Chronicle, May 13, 2012 Asian Art Museum's 'Phantoms of Asia' connects Phantoms of Asia features over 60 pieces of contemporary art playing off and connecting with the Asian Art Museum's prized historical objects. According to the writer, Phantoms of Asia, the museum’s first large-scale exhibition of contemporary art is an “an expansive and ambitious show.” Allison Harding, the Asian Art Museum's assistant curator of contemporary art says, “We're trying to create a dialogue between art of the past and art of the present, and look at the way in which artists today are exploring many of the same concerns of artists throughout time. -

Proem Shakespeare S 'Plaies and Poems"

Proem Shakespeare s 'Plaies and Poems" In 1640, the publisher John Benson presents to his English reading public a Shakespeare who is now largely lost to us: the national author of poems and plays. By printing his modest octavo edition of the Poems: Written By Wil. Shake-speare. Gent., Benson curiously aims to complement the 1623 printing venture of Shakespeare's theatre colleagues, John Heminge and Henry Condell , who had presented Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies in their monumental First Folio. Thus, in his own Dedicatory Epistle "To the Reader," Benson remarks that he presents "some excellent and sweetly composed Poems," which "had nor the fortune by reason of their lnfancie in his death, to have the due accommodation of proportionable glory, with the rest of his everliving Workes" (*2r). Indeed, as recent scholarship demonstrates, Benson boldly prints his octavo Poems on the model ofHeminge and Condell 's Folio Plays. ' Nor simply does Benson's volume share its primer, Thomas Cores, wirh rhe 1632 Folio, bur both editions begin with an identical format: an engraved portrait of the author; a dedicatory epistle "To the Reader"; and a set of commendatory verses, with Leonard Digges contributing an impor tant celebratory poem to both volumes. Benson's engraving by William Marshall even derives from the famous Martin Droeshout engraving in the First Folio, and six of the eight lines beneath Benson's engraving are borrowed from Ben Jonson's famed memorial poem to Shakespeare in char volume. Accordingly, Benson rakes his publishing goal from Heminge and Conde!!. They aim to "keepe the memory of such worthy a Friend, & Fellow alive" (Dedicatory Epistle to the earls ofPembroke and Montgomery, reprinted in Riverside, 94), while he aims "to be serviceable for the con tinuance of glory to the deserved Author" ("To the Reader," *2v). -

Shakespeare and London Programme

andShakespeare London A FREE EXHIBITION at London Metropolitan Archives from 28 May to 26 September 2013, including, at advertised times, THE SHAKESPEARE DEED A property deed signed by Mr. William Shakespeare, one of only six known examples of his signature. Also featuring documents from his lifetime along with maps, photographs, prints and models which explore his relationship with the great metropolis of LONDONHighlights will include the great panoramas of London by Hollar and Visscher, a wall of portraits of Mr Shakespeare, Mr. David Garrick’s signature, 16th century maps of the metropolis, 19th century playbills, a 1951 wooden model of The Globe Theatre and ephemera, performance recording and a gown from Shakespeare’s Globe. andShakespeare London In 1613 William Shakespeare purchased a property in Blackfriars, close to the Blackfriars Theatre and just across the river from the Globe Theatre. These were the venues used by The Kings Men (formerly the Lord Chamberlain’s Men) the performance group to which he belonged throughout most of his career. The counterpart deed he signed during the sale is one of the treasures we care for in the City of London’s collections and is on public display for the first time at London Metropolitan Archives. Celebrating the 400th anniversary of the document, this exhibition explores Shakespeare’s relationship with London through images, documents and maps drawn from the archives. From records created during his lifetime to contemporary performances of his plays, these documents follow the development of his work by dramatists and the ways in which the ‘bardologists’ have kept William Shakespeare alive in the fabric of the city through the centuries. -

SANDERS Siftings No. 57

SANDERSSiftings an exchange of Sanders/Saunders family research Number 57 April, 2009 four issues per year • $12 per year subscription • edited by Don E. Schaefer, 1297 Deane Street, Fayetteville, AR 72703-1544 Jim Sanders Searches for the Connection of It Has Been A Very Moses Sanders and Patrick Sanders Interesting 14 Years The following is the result of research Moses Saunders and a Mary Hamilton in The first issue of Sanders Siftings, of Jim Sanders, 2235 Los Encinos Road, the same, immediate geographic area as only eight pages, featured a story of Ojai, CA 93023, well as the correct time frame. The Glenn D. Sanders’ grandfather—and <[email protected]>. occurrence of the names Moses Sanders that was what got me interested in Moses Sanders/Brunswick, Va. 1772 and Mary (Hamilton) Sanders, may have taken place in other records but to our printing stories of our Sanders kin. In 1772, Moses Saunders was a knowledge, it has not been substantiated. That first issue was started with a defendant against Thomas Preston, who nucleus of people who were was a neighbor of Joseph Hamilton’s. ADD: August 2008: Francis, Moses exchanging Sanders stuff in the (Preston’s property is noted in Joseph and their brothers were very active in early days of the internet. Hamilton’s will and again in a obtaining land grants between 1771 and In that same issue were two sto- Brunswick Deed recorded in Book 7 1780 in Anson County, N.C. As shown ries by Justin Sanders, now living in Page 165). Hamilton’s property was earlier, Patrick and William left Halifax Mobile, Ala. -

1940, February

Li. _____.... d1Y l '"'T�� tt r t>' J�:� 6•1?4�' news-£e e UN<\ The SHAKESPEARE FELLOWSHIP-E.wA,HIM,rnN AMERICAN BRANCH VOL. I FEBRUARY, 1940 NO. 2 The Secret Personality of "Shakespeare" Brought to Light After Three Centuries The Ashbourne portrait (above), owned by the cally for the first time in history - with results Folger Shakespeare Library, and two other famous likely to change the whole course of Shakespearean paintings of the poet have been dissected scientifi• research. Solution of authorship mystery at hand. 2 NEWS-LETTER Scientific Proof Given that Lord Oxford Posed for Ancient Portraits of the Bard X-RAYS AND INFRA-RED PHOTOGRAPHY SHOW THAT EDWARD DE VERE, MYSTERIOUS LITERARY NOBLEMAN, IS THE REAL MAN IN THE FAMOUS ASHBOURNE "SHAKESPEARE" AND ALSO IN OTHER PAINTINGS OF ENGLAND'S GREATEST DRAMATIST. CHARLES WISNER BARRELL'S EPOCH-MAKING DISCOVERIES ARE FEATURED BY SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN AND TELEGRAPHED TO MORE THAN 2,000 NEWSPAPERS BY THE ASSOCIATED PRESS AND OTHER NEWS AGENCIES. WORK OF AMERICAN SECRETARY OF THE SHAKESPEARE FELLOW SHIP REPRESENTS A LANDMARK IN ELIZABETHAN RESEARCH AND MAY CAUSE IMMEDIATE REVALUATION OF THE COMMONLY ACCEPTED THEORY OF THE AUTHORSHIP OF THE PLAYS. Early in the morning of December 13, 1939 - It has remained for the American secretary of a date not soon to be forgotten by anyone in THE SHAKESPEARE FELLOWSHIP and a skilled terested in the pictorial record of "Mr. William group of technicians working under his direction, Shakespeare" - the news operators of the As to bring to light and accurately interpret after sociated Press began to tap out across two exhaustive corroborative studies among Eliza thousand wires leading to newspapers throughout bethan and Jacobean art, historical and genealog the length and breadth of the American continent, ical records, facts which the foremost "orthodox" a feature story that began as follows: Shakespearean authorities have completely over New York, Dec. -

Life Portraits Illian Si Ak Hart

LI F E PO RT RA I T S ” T I L L I A N S I A K H A R A HI ST O RY O F THE VAR OU RE RE ENTAT ON OF THE OET WI TH A N I S P S I S P , I N T R A T ENT TY E" A MI NAT I ON TO H E I U H I C I . 6 x 9/ B “ Y . HA N y I FR I SWE L L . ' ’ ‘ ’ ’ ’ [llzzslratm é " Pfi oto ra fis o th e most a utfiemz c Pan m z fs and wz flz ) g p f , Views "f a é C ND D NE C O . , " U ALL, OW S , T H E F F L T O N H E A D O F S B A K S P RA R F L O N D N A M P L W N O S S O N O , SO , A H L x LU DG TE L . 4 , I 1 8 64 . L O N DO N R G AY S O N A N D A \ LO P I E S , T R , R NT R , BR E A D S TR E E T H I L L THE RE SI DENT P , V C E - R E D E N T I P S I S , AND BROT HE R M EMBERS OF T HE C OMMITT EE FO R RA ISING A NAT I ONA L M EMORI A L T O P E A R E S H A K S , T HIS VOLU M E IS D EDI CAT ED BY R T HE A UT HO . -

APTG Guidelines (September 2018)

UNITE THE UNION FOR YOU GUIDELINESGUIDELINES APTG MEMBERS HAVE THEIR SAY WEBSITE LEADS SURVEY Many thanks to all those members who responded to our recent Website Leads Survey covering leads received during 2017. In total, Seventy two members completed the survey, which is about 13-14% of the membership, a figure we hope will grow in future surveys. Less than 2% said they had never had a lead from the website, whilst the majority received between one and fifty Leads. 18% had received more than fifty leads, which is pretty impressive. Not surprisingly, the majority of leads are for English-speaking guides, but we hope to increase the range of languages requested as we work to improve the website. The vast majority of enquiries are coming from individual customers and not tour operators, clearly an opportunity for us to increase the latter’s awareness of the site. Just under 80% of those who got leads converted at least one to a paid job, whilst some Guides managed to convert over twenty into jobs. For the majority of those who responded (78%), the site generates an income up to £2,000, about a fifth are earning between £2,000 and £5,000 and some guides are securing tours worth over £5,000 a year from the website. About 30% of those who confirmed tours recruited other guides to help deliver the tour, mostly just a handful, but on two occasions eight and ten guides respectively, which is a pretty good knock-on benefit of the site. Added to which, just over a quarter of guides had repeat business from clients through the John Donald out of uniform website, and some now have regular contracts. -

Is This a Shakespeare Which I See Before Me? - Nytimes.Com Page 1 of 3

Is This a Shakespeare Which I See Before Me? - NYTimes.com Page 1 of 3 This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. You can order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers here or use the "Reprints" tool that appears next to any article. Visit www.nytreprints.com for samples and additional information. Order a reprint of this article now. March 10, 2009 Is This a Shakespeare Which I See Before Me? By JOHN F. BURNS LONDON — Nearly 400 years after his death, William Shakespeare appeared in a new and more handsome guise on Monday, thanks to a recently discovered portrait that a group of Shakespeare scholars and art historians said was the only known likeness to have been painted in his lifetime. Stanley Wells, the chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, based in Shakespeare’s birthplace of Stratford-upon-Avon, described the portrait at a news conference as a “pinup.” It shows the Bard as a far more alluring figure than the solemn-faced, balding image that has been conveyed by engravings, busts and portraits that have been accepted by scholars as the best available likeness of English literature’s most famous figure. Until now, scholars have deemed the most authentic representations of Shakespeare to be a black-and-white woodcut engraving by the Flemish artist Martin Droeshout that appeared in the first folio edition of Shakespeare’s works in 1623, and a marble bust displayed since the 1620s in a Stratford church. In their place, the scholars in London showed reporters a portrait taken from the private collection of an aristocratic Anglo-Irish family, the Cobbes, who have owned it for nearly 300 years, since inheriting it through a family relationship with Shakespeare’s only known literary patron, Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton. -

2011 As You Like It

AS YOU LIKE IT Study Guide - 2011 Season Production E DIRECT AT SPEAK MACBETH THAISAGROW PROSPERO TOUCHSTONE JULIET CRE VIEW TEACH SEE CREATE HAMLET DISCUSS CLEOPATRA SEE LISTEN LAUGHROSALIND PLAY DIRECT SHYLOCKCRE LEARN CAESAR A AT ACT TEACH E OTHELLO OPHELI A Message from the Director are transformed by encountering what is “down the rabbit hole.” stark contrast to Hamlet, As IN You Like It is a play about The forest in Shakespeare’s plays is the metamorphosis of the self. always a place of transformation, a A young woman, Rosalind, is able freeing of the self from rigid societal to discover what love truly is by and parental bonds in order to pretending to be someone else, the find an authentic self. With that boy Ganymede. Through playing in mind, we have made our forest she becomes more and more into a whimsical playground where expansive, bolder and more fully objects, clothes, sound, light and herself. color are literally transformed from what they are in the court. Through Inspiration for the physical imaginative play, the characters production of As You Like It came transform themselves. from stories like The Chronicles of Narnia, Through the Looking Glass, Thank you for celebrating the and Coraline. A door is opened into human spirit with us! another world and the characters 2 Contents Shakespeare’s Life and Times ..................................................4 What Did Shakespeare Look Like? ...........................................4 Shakespeare Portrait Gallery ....................................................5 The -

Secrets of the Droeshout Shakespeare Etching

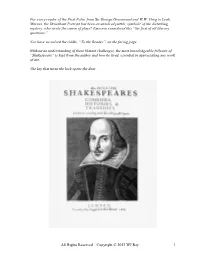

For every reader of the First Folio, from Sir George Greenwood and W.W. Greg to Leah Marcus, the Droeshout Portrait has been an unsolved puzzle, symbolic of the disturbing mystery, who wrote the canon of plays? Emerson considered this “the first of all literary questions.” Nor have we solved the riddle, “To the Reader”, on the facing page. Without an understanding of these blatant challenges, the most knowledgeable follower of “Shakespeare” is kept from the author and how he lived, essential to appreciating any work of art. The key that turns the lock opens the door. All Rights Reserved – Copyright © 2013 WJ Ray 1 Preface THE GEOMETRY OF THE DROESHOUT PORTRAIT I encourage the reader to print out the three graphics in order to follow this description. The Droeshout-based drawings are nominally accurate and to scale, based on the dimensions presented in S. Schoenbaum’s ‘William Shakespeare A Documentary Life’, p. 259’s photographic replica of the frontispiece of the First Folio, British Museum’s STC 22273, Oxford University Press, 1975. The Portrait depictions throughout the essay are from the Yale University Press’s facsimile First Folio, 1955 edition. It is particularly distinct and undamaged. In the essay that follows, a structure behind the extensive identification graphics is implied but not explained. The preface explains the hidden design. The Droeshout pictogram doubles as near-hominid portraiture, while fulfilling a profound act of allegiance and chivalric honor to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, by repeatedly locating his surname and title in the image. The surname identification is confirmed in Jonson’s facing poem. -

Coppelia Kahn's Address in Washington, D.C., 2009

Coppélia Kahn Address in Washington, D.C., 10 April 2009 At last this moment has arrived. Like all the former SAA presidents I know, I’ve been agonizing over it for two years, ever since you were so generous as to elect me vice-president. In states of low, medium and high anxiety I’ve mulled it over on two continents, waking and sleeping; during department meetings, on the exercise bicycle, in the shower and in the supermarket . I’ve juggled various topics in the air: “the battle with the Centaurs,” “the riot of the tipsy Bacchanals, / Tearing the Thracian singer in their rage,” and especially in this bleak economic season, “The thrice three Muses mourning for the death / Of Learning, late deceased in beggary” (Midsummer Night’s Dream 5.1.44-53). I think I remember my immediate predecessor, Peter Holland, whom I have never known to be at a loss for words, describing himself as lying despondent on the living room couch, like the speaker in Sidney’s sonnet, “biting [his] truant pen” and “beating [him]self for spite” as he searched for a topic for his luncheon speech. I’ve been there, too. On March 10, 2009, I was released from this state of desperation by a fast-breaking news story girdling the globe: “Is this a Shakespeare which I see before me?” read the headline on my New York Times, one of many in which reporters would show off their knowledge of Shakespeare by deliberate (or unwitting) misquotation of his words. [On screen: Cobbe portrait] There on the front page was a color photograph of a painting that Stanley Wells, chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, had presented to the world the day before as “almost certainly the only authentic image of Shakespeare made from life” (SBT press release, 3/9/09). -

The Stratford Shakespeare Monument

The Stratford Shakespeare Monument The symbolism, mystery and secret message of the Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, England. Author: Peter Dawkins Why is the Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, important? The Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, was erected sometime after the death of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon in 1616 and before the First Folio of Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies was published in 1623. Certain wording in the Folio associates Shakespeare with the Stratford monument and with a river Avon. Without this association and monument, there would be no ‘proof’ that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon had anything to do with the actual authorship of the Shakespeare plays. We would know only from historical records that he was an actor with the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later the King’s Men), the main company of players who performed the Shakespeare plays, and a co-owner of the Globe Theatre in London where the Shakespeare plays were performed for the public. The Stratford Shakespeare Monument, therefore, is a crucial piece of evidence for establishing and verifying this authorship link. However, the Stratford Shakespeare Monument is even more than this. It is a major gateway into the mystery of Shakespeare—for there is a mystery, and it is very profound and far- reaching. For one thing, it helps us to read and understand the Shakespeare Folio of plays in a better light, and to enjoy the plays in performance to a far fuller extent. It enables us to comprehend the Shakespeare sonnets and poems in a much deeper and more meaningful way.