The Stratford Shakespeare Monument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 As You Like It

AS YOU LIKE IT Study Guide - 2011 Season Production E DIRECT AT SPEAK MACBETH THAISAGROW PROSPERO TOUCHSTONE JULIET CRE VIEW TEACH SEE CREATE HAMLET DISCUSS CLEOPATRA SEE LISTEN LAUGHROSALIND PLAY DIRECT SHYLOCKCRE LEARN CAESAR A AT ACT TEACH E OTHELLO OPHELI A Message from the Director are transformed by encountering what is “down the rabbit hole.” stark contrast to Hamlet, As IN You Like It is a play about The forest in Shakespeare’s plays is the metamorphosis of the self. always a place of transformation, a A young woman, Rosalind, is able freeing of the self from rigid societal to discover what love truly is by and parental bonds in order to pretending to be someone else, the find an authentic self. With that boy Ganymede. Through playing in mind, we have made our forest she becomes more and more into a whimsical playground where expansive, bolder and more fully objects, clothes, sound, light and herself. color are literally transformed from what they are in the court. Through Inspiration for the physical imaginative play, the characters production of As You Like It came transform themselves. from stories like The Chronicles of Narnia, Through the Looking Glass, Thank you for celebrating the and Coraline. A door is opened into human spirit with us! another world and the characters 2 Contents Shakespeare’s Life and Times ..................................................4 What Did Shakespeare Look Like? ...........................................4 Shakespeare Portrait Gallery ....................................................5 The -

Coppelia Kahn's Address in Washington, D.C., 2009

Coppélia Kahn Address in Washington, D.C., 10 April 2009 At last this moment has arrived. Like all the former SAA presidents I know, I’ve been agonizing over it for two years, ever since you were so generous as to elect me vice-president. In states of low, medium and high anxiety I’ve mulled it over on two continents, waking and sleeping; during department meetings, on the exercise bicycle, in the shower and in the supermarket . I’ve juggled various topics in the air: “the battle with the Centaurs,” “the riot of the tipsy Bacchanals, / Tearing the Thracian singer in their rage,” and especially in this bleak economic season, “The thrice three Muses mourning for the death / Of Learning, late deceased in beggary” (Midsummer Night’s Dream 5.1.44-53). I think I remember my immediate predecessor, Peter Holland, whom I have never known to be at a loss for words, describing himself as lying despondent on the living room couch, like the speaker in Sidney’s sonnet, “biting [his] truant pen” and “beating [him]self for spite” as he searched for a topic for his luncheon speech. I’ve been there, too. On March 10, 2009, I was released from this state of desperation by a fast-breaking news story girdling the globe: “Is this a Shakespeare which I see before me?” read the headline on my New York Times, one of many in which reporters would show off their knowledge of Shakespeare by deliberate (or unwitting) misquotation of his words. [On screen: Cobbe portrait] There on the front page was a color photograph of a painting that Stanley Wells, chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, had presented to the world the day before as “almost certainly the only authentic image of Shakespeare made from life” (SBT press release, 3/9/09). -

The Face of Shakespeare S

Is this the face of Shakespeare? David Shakespeare May 2021 Today you are going to be looking into the the faces of William Shakespeare. The problem is which if any is genuine. Our story is set in the early 18th century and at its centre is one very interesting portrait. Let me put everything into context. The Chandos Portrait William Shakespeare had rested in posthumous an anonymity during most of the Restoration period, but interest in him was growing again in the late 17th Century with improvement in printing techniques and the growth of the entertainment industry. Later as we shall see the marketing of Shakespeare took on a distinctly political edge. A series of publications of his work began to emerge and along with the printed word came illustrations. There was therefore an obvious need for images of the face of Shakespeare. And this the so called Chandos portrait was pretty well all there was to go on, a 16th century portrait of a rather dishevelled man, which was of rather dubious authenticity !1 This the frontispiece of Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition of his works. The first to bear illustrations.The source for the engraving is not hard to recognise. Elsewhere in the publication is this illustration of William Shakespeare from Holy Trinity church Stratford upon Avon, specially made by Gerard Van der Gucht. Well not exactly. !2 He based it on a previous engraving dating from 1656 by Wenceslaus Hollar. Hollar Van der Gucht High forehead and a similar design of tunic….yes. But the tiredness has gone, and an aged face is replaced by one of bright disposition, by staring eyes, a neat beard and curly hair. -

Supplmental Material

The supplementary material contains the following information. A. Discussion of identification test cases. B. Source description for the portraits depicted in the main paper A. LIST OF FACES IDENTIFICATION TESTS Note: Test results are indicated as match/non-match/no decision as per the analysis procedure described in this paper. The images in each test are marked alphabetically and the result between possible image pairs is given. For example, for paradigm 1, the test result "match" indicates that images a and b gave a match score. "(?)" indicates that the identity of the sitter is hypothesized but uncertain. -1: Battista Sforza paradigm -a: Battista Sforza; bust; c. 1474; by Francesco Laurana (Museo nazionale del Bargello, Florence) -b: Battista Sforza (?); death mask casting; c. 1472; by Francesco Laurana (Louvre; RF 1171) Image pair under Result consideration 1a, 1b Match - This paradigm tested an analogue (an unmediated image of the subject, not a work of art) against a three- dimensional work of art that, in this case, physically approaches the subject in form and size but that nevertheless partakes of the subjectivity of artistic interpretation. The match score indicates the probability of a match, despite the obvious challenges in testing an image rendering the death throes of an individual against a work of portrait art. -2: Eva Visscher paradigm -a: Eva Visscher; c. 1685; by Michiel Van Musscher (Amsterdam, Rijksmusseum, SK-A-4233) -b: Family of the Artist; 1694-1701; by Michiel Van Musscher; the figure of the adult female is unknown, with some scholars believing that it represents the artist's first wife, Eva Visscher, and others that it portrays his second, Elsje Klanes (Antwerp, Royal Museum of Fine Arts; Inv. -

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare William Shakespeare The Chandos portrait, artist and authenticity unconfirmed. National Portrait Gallery, London. Born Baptised 26 April 1564 (birth date unknown) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Died 23 April 1616 (aged 52) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Occupation Playwright, poet, actor Nationality English Period English Renaissance Spouse(s) Anne Hathaway (m. 1582–1616) Children • Susanna Hall • Hamnet Shakespeare • Judith Quiney Relative(s) • John Shakespeare (father) • Mary Shakespeare (mother) Signature William Shakespeare (26 April 1564 (baptised) – 23 April 1616)[1] was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist.[2] He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon".[3][4] His extant works, including some collaborations, consist of about 38 plays,[5] 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and a few other verses, the authorship of some of which is uncertain. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[6] Shakespeare was born and brought up in Stratford-upon-Avon. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. Between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men, later known as the King's Men. He appears to have retired to Stratford around 1613 at age 49, where he died three years later. -

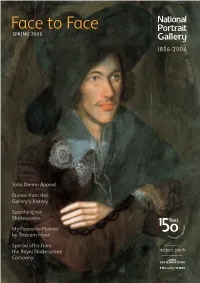

Face to Face SPRING 2006

Face to Face SPRING 2006 John Donne Appeal Stories from the Gallery’s history Searching for Shakespeare My Favourite Portrait by Tristram Hunt Special offer from the Royal Shakespeare Company From the Director ‘Often I have found a Portrait superior in real instruction to half-a-dozen written “Biographies”… or rather I have found that the Portrait was a small lighted candle by which Biographies could for the first t ime be read.’ RIGHT FROMLEFT Marjorie ‘Mo’ Mowlam by John Keane, 2001 Dame (Jean) Iris Murdoch by Tom Phillips, 1984–86 Sir Tim Berners-Lee by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, 2005 These portraits can be seen in Icons and Idols: Commissioning Contemporary Portraits from 2 March 2006 in the Porter Gallery So wrote Thomas Carlyle in 1854 in the years leading up to the founding of the National Exhibition supported by the Patrons of the National Portrail Gallery Portrait Gallery in 1856. Carlyle, with Lord Stanhope and Lord Macaulay, was one of the founding fathers of the Gallery, and his mix of admiration for the subject and interest in the character portrayed remains a strong thread through our work to this day. Much else has changed over the years since the first director, Sir George Scharf, took up his Very sadly John Hayes, Director of the National Portrait Gallery role, and as well as celebrating his achievements in a special display, we have created a from 1974 to 1994, died on timeline which outlines all the key events throughout the Gallery’s history. Our first Christmas Day aged seventy-six. -

Today You Will

Lesson plan English Qx_Layout 1 14/06/2013 11:48 Page 1 LESSON PLAN TODAY YOU WILL... GOOD WILL > THINK ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT SHAKESPEARE AND HIS POSSIBLE APPEARANCE > CONSIDER WHY IT MATTERS AT ALL THAT WE KNOW WHAT SHAKESPEARE LOOKED HUNTING LIKE AND WHAT PEOPLE MIGHT HAVE LIKED ENGLAND’S MOST FAMOUS POET’S APPEARANCE TO BE IN SUCCESSIVE GENERATIONS Before you introduce learners to the works of > BECOME A BETTER ‘READER’ OF IMAGES Shakespeare, it’s worth helping them get to know AND ALERT TO SOME OF THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SHAKESPEARE’S AGE AND OURS the man himself, suggests Jerome Monahan… YOU WILL NEED > ACCESS VIA THE WEB TO THE FOLLOWING SUPPOSED IMAGES OF SHAKESPEARE: You are about to start a Shakespeare set text with to be spoken and performed!” Then the day would 1. EXAMPLES OF SHAKESPEARE’S your students. It may be the first time they have begin, during which participants continually spoke SIGNATURE: TINYURL.COM/TSGWH2 tackled one of ‘The Works’ or they could be on and played with the text, emerging hours later 2. THE 1600S CHANDOS PORTRAIT FROM familiar ground; his plays having been part of the with lines fixed in their heads and events, themes THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY: weft and weave of their primary school days – and concepts embedded as only they can be TINYURL.COM/TSGWH3 3. THE SHAKESPEARE FUNERARY let’s hope! Still, this is a momentous occasion, and when they have been enacted. MONUMENT BY GERARD JOHNSON IN HOLY so before you crash into the world of Scotland as Some of Rex’s techniques became part of my TRINITY CHURCH, STRATFORD failed state under Macbeth; the ambiguous Illyria repertoire and have spurred me on to develop my TINYURL.COM/TSGWH4 of Twelfth Night; or Verona, the death-trap for own programme of ‘active approaches’ workshops 4. -

The JOURNAL of the RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

The JOURNAL OF THE RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES VOLUME XLI JUNE 1979 NUMBER I WHAT SHAKESPEARE LOOKED LIKE The Spielmann Position and the Alternatives BY PAUL BERTRAM Mr. Bertram teaches English at Rutgers University NYONE looking into the subject of authentic Shakespeare por- traiture will soon find his attention drawn to the expert con- Atributions of Marion H. Spielmann (1858-1948). Spielmann's first essay on the portraits appeared in 1907, his Encyclopœdia Britan- nica article appeared in 1911, and his final published word on the sub- ject, The Title-Page of the First Folio of Shakespeare's Play s, appeared in 1924. The copy in the Alexander Library at Rutgers University is in a sense more final than others, since it is a presentation copy—with a signed inscription "To Sir Bernard Partridge," who was knighted in 1925—bearing marginal corrections and revisions in the author's hand. The subtitle of Spielmann's book, A Comparative Study of the Droes- hout Portrait and the Stratford Monument, refers to the two images of Shakespeare against which the claim to authenticity of all others is normally measured. The engraved portrait on the title-page of the Folio, signed at the lower left by Martin Droeshout, was presumably com- missioned by John Hemmings and Henry Condell (the overseers of the edition) and since 1623 has probably been the most widely repro- duced of all pictures of Shakespeare. The other portrait is the painted limestone bust in the Stratford funeral monument, attributed to Gerard Johnson II, showing an older and puffier-faced man than in the Droes- hout picture. -

Lesson Plan English Qx Layout 1 14/06/2013 11:48 Page 1

Lesson plan English Qx_Layout 1 14/06/2013 11:48 Page 1 LESSON PLAN TODAY YOU WILL... GOOD WILL > THINK ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT SHAKESPEARE AND HIS POSSIBLE APPEARANCE > CONSIDER WHY IT MATTERS AT ALL THAT WE KNOW WHAT SHAKESPEARE LOOKED HUNTING LIKE AND WHAT PEOPLE MIGHT HAVE LIKED ENGLAND’S MOST FAMOUS POET’S APPEARANCE TO BE IN SUCCESSIVE GENERATIONS Before you introduce learners to the works of > BECOME A BETTER ‘READER’ OF IMAGES Shakespeare, it’s worth helping them get to know AND ALERT TO SOME OF THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SHAKESPEARE’S AGE AND OURS the man himself, suggests Jerome Monahan… YOU WILL NEED > ACCESS VIA THE WEB TO THE FOLLOWING SUPPOSED IMAGES OF SHAKESPEARE: You are about to start a Shakespeare set text with to be spoken and performed!” Then the day would 1. EXAMPLES OF SHAKESPEARE’S your students. It may be the first time they have begin, during which participants continually spoke SIGNATURE: TINYURL.COM/TSGWH2 tackled one of ‘The Works’ or they could be on and played with the text, emerging hours later 2. THE 1600S CHANDOS PORTRAIT FROM familiar ground; his plays having been part of the with lines fixed in their heads and events, themes THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY: weft and weave of their primary school days – and concepts embedded as only they can be TINYURL.COM/TSGWH3 3. THE SHAKESPEARE FUNERARY let’s hope! Still, this is a momentous occasion, and when they have been enacted. MONUMENT BY GERARD JOHNSON IN HOLY so before you crash into the world of Scotland as Some of Rex’s techniques became part of my TRINITY CHURCH, STRATFORD failed state under Macbeth; the ambiguous Illyria repertoire and have spurred me on to develop my TINYURL.COM/TSGWH4 of Twelfth Night; or Verona, the death-trap for own programme of ‘active approaches’ workshops 4. -

ART CRITIC STARTS NEW SHAKESPEARE CONTROVERSY the Casa Ofggeorgo Washington

THE SUN, SUNDAY, MARCH 3, 1912. 11 ART CRITIC STARTS NEW SHAKESPEARE CONTROVERSY the casa ofgGeorgo Washington. Wero montators upon the linos ,of Bon Jonson to originality. It Is, as I raiy say, tho Marion H. Spielmann Denies Authenticity of Accepted It not for tho faot that no was. a careful, which alwayB accompany tho print: key to unlock and detect almost all tho False Dates on Prints Alleged Recollections Revived painstaking man, whoso diury carefully Tbla Figure, that thou here aee'at put, impositions that have at various times Portraits of Bard, and Asks recorded overy Rittlng which ho gave for a It (or gantle .Shakespeare cut; arrested so much of public attention. It That Body Be Ex- picture, we would be In great doubt about Wherein the (iraver had a atrlfs It a witness that can refuto all false co of the Baconian Agitation Satirical Criticism many of his portraits. There is a' vory With Nature, to out do the lire: and will satisfy every dlscorner humed in Order to Decide for All difference many O couM he but have drawno hit wit how to approolato how to Would-B- e Authorities marked in of his accepted As well In brase, as he hath hit and convict." of on Portraits Time plotures, some of which would bo declared Ills Tare; the print would then lurpao) Tho Stratford bust Is hardly les soouro What He Looked Like. not gcnulno wero It not for the written All that waa ever writ In braase. In its position. Nevor before Mr. Is Stratford Bust Authentic ? records whloh ho himself loft." Ilut, tlnce he cannot, Header, looks, matin has any ono suggostod that It was A new Shakospcarlm controversy has raask, valued at $50,000 and an object of A closo Not on hta Picture, but his Ilooke. -

Who Wrote Shakespeare? (Illustrated.) the Shakespeare Family

XLbc ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE H)evote^ to tbc Science of IReUaion, tbe IReliQion ot Science, an& tbe Brtenaion ot tbe IReliaious parliament f&ea Ediior: D«. Paul Cahos. Associates: **' j Mary Cab's VOL. XVIII. (no. 2) February, 1904. NO. 573 CONTENTS: Frontispiece. The Chandos Portrait of Shakespeare. Who Wrote Shakespeare? (Illustrated.) The Shakespeare Family. John Shakespeare the Glover and His Son. —The Will and the Tomb- stones of the Shakespeare Family. —The Poet. —The Identification and the Stratford Monument. —The Tombstones of Dr. and Mrs. Hall. —The Posthumous Folio Edition. —Vicar Ward's Testimony. —Ben Jonson's Testimony. —Legends. —Biographies. —Our Conjec- ture, —Portrayals of the Poet. —Conclusion. Editor 65 The Japanese Floral Calendar. (Illustrated.) The Plum. Ernest W. Clement, M. A 107 Some Account of the Life of William Shakespeare. Nicholas Rowe . 113 Satire, *^ Praise Hypocrisy." Dr. Knighfs The of Dr. J. R. Phelps . 117 Prof. Karl Pearson on the Law of Progress 118 An Octogenarian Buddhist High Priest. (With Photograph. ) 122 My House. A Poem. E. A. Brackett 124 Book Reviews and Notes 124 CHICAGO Ube ©pen Court IpubUdbing Compani^ LONDON : Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner & Co., Ltd. Per copy, 10 cenU (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (Id the U. P. U., 58. 6d.). Copyright, 1904, by The Open Court Publishing Co. Batered at the Cbicaco Pott 0fiC3 •• Seeond-CtaM Matter ^be ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE H)cvote^ to the Science of IRelialon, tbe IRellaion ot Science, anb tbe Extension ot tbe IReligious parliament 1^ea Editor: Dii. Paul Carus. Associates: | J^^; Caboi**' VOL. XVIII. (no. -

Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel Much Ado About Nothing: Why The

Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel Much Ado About Nothing: why the Cobbe portrait is not an authentic, true-to-life portrait of William Shakespeare The genius of William Shakespeare, the creator of immortal works for the stage who is celebrated today as an icon of world literature, was already fully recognised in his own day. One drama in particular, Hamlet, after 400 years still among the most fascinating, most read, most frequently staged, most discussed and surely most intensively studied plays of all time, had a profound emotional effect on its contemporary audience, in part because of its dangerous political content. However, the student youth of his day had a penchant for Romeo and Juliet, and eagerly devoured his lubricious verse epic, Venus and Adonis. According to one literary source, they kept a copy of the text under their pillow, and hung a picture of the author above their bed. Despite his illustrious literary career, the playwright was only 49 years old when he withdrew to the seclusion of his Stratford retreat. He died three years later – probably as the result of a systemic skin sarcoidosis, an internal disease to which all organs are vulnerable, and which leads to death normally after many years. The outer signs of this illness can be seen in all four likenesses of Shakespeare whose authenticity I have been able to establish,* working closely with many scientists and academics from other disciplines, including a number of medics and experts from the German Federal Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BKA = CID or FBI). All the tests used to establish identity led to the same unexpected and sensational result, namely that all the images investigated show the same man: William Shakespeare, taken from life.