The JOURNAL of the RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proem Shakespeare S 'Plaies and Poems"

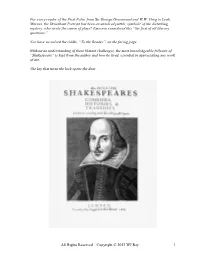

Proem Shakespeare s 'Plaies and Poems" In 1640, the publisher John Benson presents to his English reading public a Shakespeare who is now largely lost to us: the national author of poems and plays. By printing his modest octavo edition of the Poems: Written By Wil. Shake-speare. Gent., Benson curiously aims to complement the 1623 printing venture of Shakespeare's theatre colleagues, John Heminge and Henry Condell , who had presented Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies in their monumental First Folio. Thus, in his own Dedicatory Epistle "To the Reader," Benson remarks that he presents "some excellent and sweetly composed Poems," which "had nor the fortune by reason of their lnfancie in his death, to have the due accommodation of proportionable glory, with the rest of his everliving Workes" (*2r). Indeed, as recent scholarship demonstrates, Benson boldly prints his octavo Poems on the model ofHeminge and Condell 's Folio Plays. ' Nor simply does Benson's volume share its primer, Thomas Cores, wirh rhe 1632 Folio, bur both editions begin with an identical format: an engraved portrait of the author; a dedicatory epistle "To the Reader"; and a set of commendatory verses, with Leonard Digges contributing an impor tant celebratory poem to both volumes. Benson's engraving by William Marshall even derives from the famous Martin Droeshout engraving in the First Folio, and six of the eight lines beneath Benson's engraving are borrowed from Ben Jonson's famed memorial poem to Shakespeare in char volume. Accordingly, Benson rakes his publishing goal from Heminge and Conde!!. They aim to "keepe the memory of such worthy a Friend, & Fellow alive" (Dedicatory Epistle to the earls ofPembroke and Montgomery, reprinted in Riverside, 94), while he aims "to be serviceable for the con tinuance of glory to the deserved Author" ("To the Reader," *2v). -

Shakespeare and London Programme

andShakespeare London A FREE EXHIBITION at London Metropolitan Archives from 28 May to 26 September 2013, including, at advertised times, THE SHAKESPEARE DEED A property deed signed by Mr. William Shakespeare, one of only six known examples of his signature. Also featuring documents from his lifetime along with maps, photographs, prints and models which explore his relationship with the great metropolis of LONDONHighlights will include the great panoramas of London by Hollar and Visscher, a wall of portraits of Mr Shakespeare, Mr. David Garrick’s signature, 16th century maps of the metropolis, 19th century playbills, a 1951 wooden model of The Globe Theatre and ephemera, performance recording and a gown from Shakespeare’s Globe. andShakespeare London In 1613 William Shakespeare purchased a property in Blackfriars, close to the Blackfriars Theatre and just across the river from the Globe Theatre. These were the venues used by The Kings Men (formerly the Lord Chamberlain’s Men) the performance group to which he belonged throughout most of his career. The counterpart deed he signed during the sale is one of the treasures we care for in the City of London’s collections and is on public display for the first time at London Metropolitan Archives. Celebrating the 400th anniversary of the document, this exhibition explores Shakespeare’s relationship with London through images, documents and maps drawn from the archives. From records created during his lifetime to contemporary performances of his plays, these documents follow the development of his work by dramatists and the ways in which the ‘bardologists’ have kept William Shakespeare alive in the fabric of the city through the centuries. -

1940, February

Li. _____.... d1Y l '"'T�� tt r t>' J�:� 6•1?4�' news-£e e UN<\ The SHAKESPEARE FELLOWSHIP-E.wA,HIM,rnN AMERICAN BRANCH VOL. I FEBRUARY, 1940 NO. 2 The Secret Personality of "Shakespeare" Brought to Light After Three Centuries The Ashbourne portrait (above), owned by the cally for the first time in history - with results Folger Shakespeare Library, and two other famous likely to change the whole course of Shakespearean paintings of the poet have been dissected scientifi• research. Solution of authorship mystery at hand. 2 NEWS-LETTER Scientific Proof Given that Lord Oxford Posed for Ancient Portraits of the Bard X-RAYS AND INFRA-RED PHOTOGRAPHY SHOW THAT EDWARD DE VERE, MYSTERIOUS LITERARY NOBLEMAN, IS THE REAL MAN IN THE FAMOUS ASHBOURNE "SHAKESPEARE" AND ALSO IN OTHER PAINTINGS OF ENGLAND'S GREATEST DRAMATIST. CHARLES WISNER BARRELL'S EPOCH-MAKING DISCOVERIES ARE FEATURED BY SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN AND TELEGRAPHED TO MORE THAN 2,000 NEWSPAPERS BY THE ASSOCIATED PRESS AND OTHER NEWS AGENCIES. WORK OF AMERICAN SECRETARY OF THE SHAKESPEARE FELLOW SHIP REPRESENTS A LANDMARK IN ELIZABETHAN RESEARCH AND MAY CAUSE IMMEDIATE REVALUATION OF THE COMMONLY ACCEPTED THEORY OF THE AUTHORSHIP OF THE PLAYS. Early in the morning of December 13, 1939 - It has remained for the American secretary of a date not soon to be forgotten by anyone in THE SHAKESPEARE FELLOWSHIP and a skilled terested in the pictorial record of "Mr. William group of technicians working under his direction, Shakespeare" - the news operators of the As to bring to light and accurately interpret after sociated Press began to tap out across two exhaustive corroborative studies among Eliza thousand wires leading to newspapers throughout bethan and Jacobean art, historical and genealog the length and breadth of the American continent, ical records, facts which the foremost "orthodox" a feature story that began as follows: Shakespearean authorities have completely over New York, Dec. -

English 725: Shakespeare: Tragedies Week 1 Organization Romeo and Juliet. Acts

English 725: Shakespeare: Tragedies Week 1 Organization Romeo and Juliet. Acts 1-2 Week 2 Romeo and Juliet. Acts 3-5 Romeo and Juliet Week 3: Julius Caesar, Acts 1-2 Julius Caesar, Acts 3-5 Week 4: Julius Caesar Review Week 5: EXAM: Take Home Hamlet, Acts 1-2 Week 6: Hamlet, 3-5 Hamlet Week 7: Hamlet Othello, Acts. 1-2 Week 8: Othello, Acts 3-5 Othello Week 9: Review of Hamlet and Othello Week 10: King Lear, Acts 1-2 King Lear, Acts 3-5 Week 11: King Lear Macbeth, Acts 1-2 Week 12: Macbeth, Acts 3-5 Macbeth Week 13: The Winter’s Tale, Acts 1-2 The Winter’s Tale, Acts 3-5 Week 14 The Winter’s Tale Paper Due: (Submitted online by 5:00 P.M.) Week 15 Review Review Final Exam: Take Home Exam Assignments: --One in class report; 20-30 minutes (see topics below) --Complete reading assignment before each class. --One take home midterm exam; one take home final exam. --One 4000-6000 word paper: due April 28. Topics listed below. To be submitted online by 5:00 P.M. Early drafts of the paper may be submitted for me to return and read no later than one week before the due date. --Final exam: Take Home Exam Learning objectives: Through classroom discussion and original written criticism, students will be able to explain the historical importance of Shakespeare’s tragedies as works of art and as historical documents. Students will learn how to analyze, evaluate, and employ interpretative approaches in speaking and writing about Shakespeare and will develop a professional competency in critical thinking and writing about literature. -

Human Kind Transforming Identity in British and Australian Portraits 1700-1914

HUMAN KIND TRANSFORMING IDENTITY IN BRITISH AND AUSTRALIAN PORTRAITS 1700-1914 International Conference on Portraiture University of Melbourne and National Gallery of Victoria Conference Programme Thursday 8 September – Sunday 11 September 2016 Biographies of Speakers and Abstracts of their Papers [In chronological order: Speaker, title of paper, organisation, bio, abstract of paper] Speakers: Leonard Bell, University of Auckland, Who was John Rutherford? John Dempsey’s Portrait of the ‘Tattooed Englishman’ c.1829 Bio: Dr Leonard (Len) Bell is an Associate Professor in Art History, School of Humanities, The University of Auckland. His writings on cross-cultural interactions and the visual arts in New Zealand, Australia and the Pacific have been published in books and periodicals in New Zealand, Australia, Britain, USA, Germany, the Czech Republic and Japan. His books include The Maori in European Art: A Survey of the Representation of the Maori from the Time of Captain Cook to the Present Day (1980), Colonial Constructs: European Images of Maori 1840–1914 (1992), In Transit: Questions of Home and Belonging in New Zealand Art (2007), Marti Friedlander (2009 & 2010), From Prague to Auckland: The Photographs of Frank Hofmann (1916-89), (2011), and Jewish Lives in New Zealand: A History (2012: co-editor & principal writer). His essays have appeared in Julie Codell & Dianne Sachko Macleod (eds), Orientalism Transformed: The Impact of the Colonies on British Art (1998), Alex Calder, Jonathan Lamb & Bridget Orr (eds), Voyages and Beaches: Pacific Encounters 1769-1840 (1999), Nicholas Thomas & Diane Losche (eds), Double Vision: Art Histories and Colonial Histories in the Pacific (1999), Felix Driver & Luciana Martins (eds), Tropical Visions in an Age of Empire (2005), Annie Coombes (ed), Rethinking Settler Colonialism: History and Memory in Australia, Canada, Aotearoa/New Zealand and South Africa (2006) and Tim Barringer, Geoff Quilley & Douglas Fordham (eds), Art and the British Empire (2007). -

2011 As You Like It

AS YOU LIKE IT Study Guide - 2011 Season Production E DIRECT AT SPEAK MACBETH THAISAGROW PROSPERO TOUCHSTONE JULIET CRE VIEW TEACH SEE CREATE HAMLET DISCUSS CLEOPATRA SEE LISTEN LAUGHROSALIND PLAY DIRECT SHYLOCKCRE LEARN CAESAR A AT ACT TEACH E OTHELLO OPHELI A Message from the Director are transformed by encountering what is “down the rabbit hole.” stark contrast to Hamlet, As IN You Like It is a play about The forest in Shakespeare’s plays is the metamorphosis of the self. always a place of transformation, a A young woman, Rosalind, is able freeing of the self from rigid societal to discover what love truly is by and parental bonds in order to pretending to be someone else, the find an authentic self. With that boy Ganymede. Through playing in mind, we have made our forest she becomes more and more into a whimsical playground where expansive, bolder and more fully objects, clothes, sound, light and herself. color are literally transformed from what they are in the court. Through Inspiration for the physical imaginative play, the characters production of As You Like It came transform themselves. from stories like The Chronicles of Narnia, Through the Looking Glass, Thank you for celebrating the and Coraline. A door is opened into human spirit with us! another world and the characters 2 Contents Shakespeare’s Life and Times ..................................................4 What Did Shakespeare Look Like? ...........................................4 Shakespeare Portrait Gallery ....................................................5 The -

Secrets of the Droeshout Shakespeare Etching

For every reader of the First Folio, from Sir George Greenwood and W.W. Greg to Leah Marcus, the Droeshout Portrait has been an unsolved puzzle, symbolic of the disturbing mystery, who wrote the canon of plays? Emerson considered this “the first of all literary questions.” Nor have we solved the riddle, “To the Reader”, on the facing page. Without an understanding of these blatant challenges, the most knowledgeable follower of “Shakespeare” is kept from the author and how he lived, essential to appreciating any work of art. The key that turns the lock opens the door. All Rights Reserved – Copyright © 2013 WJ Ray 1 Preface THE GEOMETRY OF THE DROESHOUT PORTRAIT I encourage the reader to print out the three graphics in order to follow this description. The Droeshout-based drawings are nominally accurate and to scale, based on the dimensions presented in S. Schoenbaum’s ‘William Shakespeare A Documentary Life’, p. 259’s photographic replica of the frontispiece of the First Folio, British Museum’s STC 22273, Oxford University Press, 1975. The Portrait depictions throughout the essay are from the Yale University Press’s facsimile First Folio, 1955 edition. It is particularly distinct and undamaged. In the essay that follows, a structure behind the extensive identification graphics is implied but not explained. The preface explains the hidden design. The Droeshout pictogram doubles as near-hominid portraiture, while fulfilling a profound act of allegiance and chivalric honor to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, by repeatedly locating his surname and title in the image. The surname identification is confirmed in Jonson’s facing poem. -

Coppelia Kahn's Address in Washington, D.C., 2009

Coppélia Kahn Address in Washington, D.C., 10 April 2009 At last this moment has arrived. Like all the former SAA presidents I know, I’ve been agonizing over it for two years, ever since you were so generous as to elect me vice-president. In states of low, medium and high anxiety I’ve mulled it over on two continents, waking and sleeping; during department meetings, on the exercise bicycle, in the shower and in the supermarket . I’ve juggled various topics in the air: “the battle with the Centaurs,” “the riot of the tipsy Bacchanals, / Tearing the Thracian singer in their rage,” and especially in this bleak economic season, “The thrice three Muses mourning for the death / Of Learning, late deceased in beggary” (Midsummer Night’s Dream 5.1.44-53). I think I remember my immediate predecessor, Peter Holland, whom I have never known to be at a loss for words, describing himself as lying despondent on the living room couch, like the speaker in Sidney’s sonnet, “biting [his] truant pen” and “beating [him]self for spite” as he searched for a topic for his luncheon speech. I’ve been there, too. On March 10, 2009, I was released from this state of desperation by a fast-breaking news story girdling the globe: “Is this a Shakespeare which I see before me?” read the headline on my New York Times, one of many in which reporters would show off their knowledge of Shakespeare by deliberate (or unwitting) misquotation of his words. [On screen: Cobbe portrait] There on the front page was a color photograph of a painting that Stanley Wells, chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, had presented to the world the day before as “almost certainly the only authentic image of Shakespeare made from life” (SBT press release, 3/9/09). -

The Stratford Shakespeare Monument

The Stratford Shakespeare Monument The symbolism, mystery and secret message of the Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, England. Author: Peter Dawkins Why is the Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, important? The Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, was erected sometime after the death of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon in 1616 and before the First Folio of Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies was published in 1623. Certain wording in the Folio associates Shakespeare with the Stratford monument and with a river Avon. Without this association and monument, there would be no ‘proof’ that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon had anything to do with the actual authorship of the Shakespeare plays. We would know only from historical records that he was an actor with the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later the King’s Men), the main company of players who performed the Shakespeare plays, and a co-owner of the Globe Theatre in London where the Shakespeare plays were performed for the public. The Stratford Shakespeare Monument, therefore, is a crucial piece of evidence for establishing and verifying this authorship link. However, the Stratford Shakespeare Monument is even more than this. It is a major gateway into the mystery of Shakespeare—for there is a mystery, and it is very profound and far- reaching. For one thing, it helps us to read and understand the Shakespeare Folio of plays in a better light, and to enjoy the plays in performance to a far fuller extent. It enables us to comprehend the Shakespeare sonnets and poems in a much deeper and more meaningful way. -

The Face of Shakespeare S

Is this the face of Shakespeare? David Shakespeare May 2021 Today you are going to be looking into the the faces of William Shakespeare. The problem is which if any is genuine. Our story is set in the early 18th century and at its centre is one very interesting portrait. Let me put everything into context. The Chandos Portrait William Shakespeare had rested in posthumous an anonymity during most of the Restoration period, but interest in him was growing again in the late 17th Century with improvement in printing techniques and the growth of the entertainment industry. Later as we shall see the marketing of Shakespeare took on a distinctly political edge. A series of publications of his work began to emerge and along with the printed word came illustrations. There was therefore an obvious need for images of the face of Shakespeare. And this the so called Chandos portrait was pretty well all there was to go on, a 16th century portrait of a rather dishevelled man, which was of rather dubious authenticity !1 This the frontispiece of Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition of his works. The first to bear illustrations.The source for the engraving is not hard to recognise. Elsewhere in the publication is this illustration of William Shakespeare from Holy Trinity church Stratford upon Avon, specially made by Gerard Van der Gucht. Well not exactly. !2 He based it on a previous engraving dating from 1656 by Wenceslaus Hollar. Hollar Van der Gucht High forehead and a similar design of tunic….yes. But the tiredness has gone, and an aged face is replaced by one of bright disposition, by staring eyes, a neat beard and curly hair. -

Bibliography Sources for Further Reading May 2011 National Trust Bibliography

Bibliography Sources for further reading May 2011 National Trust Bibliography Introduction Over many years a great deal has been published about the properties and collections in the care of the National Trust, yet to date no single record of those publications has been established. The following Bibliography is a first attempt to do just that, and provides a starting point for those who want to learn more about the properties and collections in the National Trust’s care. Inevitably this list will have gaps in it. Do please let us know of additional material that you feel might be included, or where you have spotted errors in the existing entries. All feedback to [email protected] would be very welcome. Please note the Bibliography does not include minor references within large reference works, such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica, or to guidebooks published by the National Trust. How to use The Bibliography is arranged by property, and then alphabetically by author. For ease of use, clicking on a hyperlink will take you from a property name listed on the Contents Page to the page for that property. ‘Return to Contents’ hyperlinks will take you back to the contents page. To search by particular terms, such as author or a theme, please make use of the ‘Find’ function, in the ‘Edit’ menu (or use the keyboard shortcut ‘[Ctrl] + [F]’). Locating copies of books, journals or specific articles Most of the books, and some journals and magazines, can of course be found in any good library. For access to rarer titles a visit to one of the country’s copyright libraries may be necessary. -

Supplmental Material

The supplementary material contains the following information. A. Discussion of identification test cases. B. Source description for the portraits depicted in the main paper A. LIST OF FACES IDENTIFICATION TESTS Note: Test results are indicated as match/non-match/no decision as per the analysis procedure described in this paper. The images in each test are marked alphabetically and the result between possible image pairs is given. For example, for paradigm 1, the test result "match" indicates that images a and b gave a match score. "(?)" indicates that the identity of the sitter is hypothesized but uncertain. -1: Battista Sforza paradigm -a: Battista Sforza; bust; c. 1474; by Francesco Laurana (Museo nazionale del Bargello, Florence) -b: Battista Sforza (?); death mask casting; c. 1472; by Francesco Laurana (Louvre; RF 1171) Image pair under Result consideration 1a, 1b Match - This paradigm tested an analogue (an unmediated image of the subject, not a work of art) against a three- dimensional work of art that, in this case, physically approaches the subject in form and size but that nevertheless partakes of the subjectivity of artistic interpretation. The match score indicates the probability of a match, despite the obvious challenges in testing an image rendering the death throes of an individual against a work of portrait art. -2: Eva Visscher paradigm -a: Eva Visscher; c. 1685; by Michiel Van Musscher (Amsterdam, Rijksmusseum, SK-A-4233) -b: Family of the Artist; 1694-1701; by Michiel Van Musscher; the figure of the adult female is unknown, with some scholars believing that it represents the artist's first wife, Eva Visscher, and others that it portrays his second, Elsje Klanes (Antwerp, Royal Museum of Fine Arts; Inv.