Shakspere's Portraiture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proem Shakespeare S 'Plaies and Poems"

Proem Shakespeare s 'Plaies and Poems" In 1640, the publisher John Benson presents to his English reading public a Shakespeare who is now largely lost to us: the national author of poems and plays. By printing his modest octavo edition of the Poems: Written By Wil. Shake-speare. Gent., Benson curiously aims to complement the 1623 printing venture of Shakespeare's theatre colleagues, John Heminge and Henry Condell , who had presented Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies in their monumental First Folio. Thus, in his own Dedicatory Epistle "To the Reader," Benson remarks that he presents "some excellent and sweetly composed Poems," which "had nor the fortune by reason of their lnfancie in his death, to have the due accommodation of proportionable glory, with the rest of his everliving Workes" (*2r). Indeed, as recent scholarship demonstrates, Benson boldly prints his octavo Poems on the model ofHeminge and Condell 's Folio Plays. ' Nor simply does Benson's volume share its primer, Thomas Cores, wirh rhe 1632 Folio, bur both editions begin with an identical format: an engraved portrait of the author; a dedicatory epistle "To the Reader"; and a set of commendatory verses, with Leonard Digges contributing an impor tant celebratory poem to both volumes. Benson's engraving by William Marshall even derives from the famous Martin Droeshout engraving in the First Folio, and six of the eight lines beneath Benson's engraving are borrowed from Ben Jonson's famed memorial poem to Shakespeare in char volume. Accordingly, Benson rakes his publishing goal from Heminge and Conde!!. They aim to "keepe the memory of such worthy a Friend, & Fellow alive" (Dedicatory Epistle to the earls ofPembroke and Montgomery, reprinted in Riverside, 94), while he aims "to be serviceable for the con tinuance of glory to the deserved Author" ("To the Reader," *2v). -

Life Portraits Illian Si Ak Hart

LI F E PO RT RA I T S ” T I L L I A N S I A K H A R A HI ST O RY O F THE VAR OU RE RE ENTAT ON OF THE OET WI TH A N I S P S I S P , I N T R A T ENT TY E" A MI NAT I ON TO H E I U H I C I . 6 x 9/ B “ Y . HA N y I FR I SWE L L . ' ’ ‘ ’ ’ ’ [llzzslratm é " Pfi oto ra fis o th e most a utfiemz c Pan m z fs and wz flz ) g p f , Views "f a é C ND D NE C O . , " U ALL, OW S , T H E F F L T O N H E A D O F S B A K S P RA R F L O N D N A M P L W N O S S O N O , SO , A H L x LU DG TE L . 4 , I 1 8 64 . L O N DO N R G AY S O N A N D A \ LO P I E S , T R , R NT R , BR E A D S TR E E T H I L L THE RE SI DENT P , V C E - R E D E N T I P S I S , AND BROT HE R M EMBERS OF T HE C OMMITT EE FO R RA ISING A NAT I ONA L M EMORI A L T O P E A R E S H A K S , T HIS VOLU M E IS D EDI CAT ED BY R T HE A UT HO . -

2011 As You Like It

AS YOU LIKE IT Study Guide - 2011 Season Production E DIRECT AT SPEAK MACBETH THAISAGROW PROSPERO TOUCHSTONE JULIET CRE VIEW TEACH SEE CREATE HAMLET DISCUSS CLEOPATRA SEE LISTEN LAUGHROSALIND PLAY DIRECT SHYLOCKCRE LEARN CAESAR A AT ACT TEACH E OTHELLO OPHELI A Message from the Director are transformed by encountering what is “down the rabbit hole.” stark contrast to Hamlet, As IN You Like It is a play about The forest in Shakespeare’s plays is the metamorphosis of the self. always a place of transformation, a A young woman, Rosalind, is able freeing of the self from rigid societal to discover what love truly is by and parental bonds in order to pretending to be someone else, the find an authentic self. With that boy Ganymede. Through playing in mind, we have made our forest she becomes more and more into a whimsical playground where expansive, bolder and more fully objects, clothes, sound, light and herself. color are literally transformed from what they are in the court. Through Inspiration for the physical imaginative play, the characters production of As You Like It came transform themselves. from stories like The Chronicles of Narnia, Through the Looking Glass, Thank you for celebrating the and Coraline. A door is opened into human spirit with us! another world and the characters 2 Contents Shakespeare’s Life and Times ..................................................4 What Did Shakespeare Look Like? ...........................................4 Shakespeare Portrait Gallery ....................................................5 The -

Secrets of the Droeshout Shakespeare Etching

For every reader of the First Folio, from Sir George Greenwood and W.W. Greg to Leah Marcus, the Droeshout Portrait has been an unsolved puzzle, symbolic of the disturbing mystery, who wrote the canon of plays? Emerson considered this “the first of all literary questions.” Nor have we solved the riddle, “To the Reader”, on the facing page. Without an understanding of these blatant challenges, the most knowledgeable follower of “Shakespeare” is kept from the author and how he lived, essential to appreciating any work of art. The key that turns the lock opens the door. All Rights Reserved – Copyright © 2013 WJ Ray 1 Preface THE GEOMETRY OF THE DROESHOUT PORTRAIT I encourage the reader to print out the three graphics in order to follow this description. The Droeshout-based drawings are nominally accurate and to scale, based on the dimensions presented in S. Schoenbaum’s ‘William Shakespeare A Documentary Life’, p. 259’s photographic replica of the frontispiece of the First Folio, British Museum’s STC 22273, Oxford University Press, 1975. The Portrait depictions throughout the essay are from the Yale University Press’s facsimile First Folio, 1955 edition. It is particularly distinct and undamaged. In the essay that follows, a structure behind the extensive identification graphics is implied but not explained. The preface explains the hidden design. The Droeshout pictogram doubles as near-hominid portraiture, while fulfilling a profound act of allegiance and chivalric honor to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, by repeatedly locating his surname and title in the image. The surname identification is confirmed in Jonson’s facing poem. -

Coppelia Kahn's Address in Washington, D.C., 2009

Coppélia Kahn Address in Washington, D.C., 10 April 2009 At last this moment has arrived. Like all the former SAA presidents I know, I’ve been agonizing over it for two years, ever since you were so generous as to elect me vice-president. In states of low, medium and high anxiety I’ve mulled it over on two continents, waking and sleeping; during department meetings, on the exercise bicycle, in the shower and in the supermarket . I’ve juggled various topics in the air: “the battle with the Centaurs,” “the riot of the tipsy Bacchanals, / Tearing the Thracian singer in their rage,” and especially in this bleak economic season, “The thrice three Muses mourning for the death / Of Learning, late deceased in beggary” (Midsummer Night’s Dream 5.1.44-53). I think I remember my immediate predecessor, Peter Holland, whom I have never known to be at a loss for words, describing himself as lying despondent on the living room couch, like the speaker in Sidney’s sonnet, “biting [his] truant pen” and “beating [him]self for spite” as he searched for a topic for his luncheon speech. I’ve been there, too. On March 10, 2009, I was released from this state of desperation by a fast-breaking news story girdling the globe: “Is this a Shakespeare which I see before me?” read the headline on my New York Times, one of many in which reporters would show off their knowledge of Shakespeare by deliberate (or unwitting) misquotation of his words. [On screen: Cobbe portrait] There on the front page was a color photograph of a painting that Stanley Wells, chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, had presented to the world the day before as “almost certainly the only authentic image of Shakespeare made from life” (SBT press release, 3/9/09). -

The Stratford Shakespeare Monument

The Stratford Shakespeare Monument The symbolism, mystery and secret message of the Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, England. Author: Peter Dawkins Why is the Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, important? The Shakespeare Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, was erected sometime after the death of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon in 1616 and before the First Folio of Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies was published in 1623. Certain wording in the Folio associates Shakespeare with the Stratford monument and with a river Avon. Without this association and monument, there would be no ‘proof’ that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon had anything to do with the actual authorship of the Shakespeare plays. We would know only from historical records that he was an actor with the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later the King’s Men), the main company of players who performed the Shakespeare plays, and a co-owner of the Globe Theatre in London where the Shakespeare plays were performed for the public. The Stratford Shakespeare Monument, therefore, is a crucial piece of evidence for establishing and verifying this authorship link. However, the Stratford Shakespeare Monument is even more than this. It is a major gateway into the mystery of Shakespeare—for there is a mystery, and it is very profound and far- reaching. For one thing, it helps us to read and understand the Shakespeare Folio of plays in a better light, and to enjoy the plays in performance to a far fuller extent. It enables us to comprehend the Shakespeare sonnets and poems in a much deeper and more meaningful way. -

GON/4* Founded 1886 a J*

p VOL. XLIX. No. 166 PRICE 10/- POST FREE : GON/4* Founded 1886 A j* June, 1966 A CONTENTS Editorial 1 Times Literary Supplement Correspondence 11 r *! Obituaries ... 16 The Stratford Tragi-Comedy 19 Shakespeare Dethroned 42 Odd Numbers 108 Bacon’s Reputation ... 123 - Correspondence 139 Shakespeare Quatercentenary Report © Published Periodically LONDON: Published by The Francis Bacon Society Incorporated at Canonbury Tower, Islington, London, N.l, and printed by Lightbowns Ltd., 72 Union Street, Ryde, Isle of Wight. I THE FRANCIS BACON SOCIETY ■ (incorporated) ; Among the Objects for which the Society is established, as expressed in the Memorandum of Association, are the following: 1. To encourage for the benefit of the public, the study of the works of Francis Bacon as philosopher, statesman and poet; also his character, genius and life; his influence on his own and succeeding times, and the tendencies and results ; of his writing. 2. To encourage for the benefit of the public, the general study of the evidence in favour of Francis Bacon’s authorship of the plays commonly ascribed to Shakespeare, and to investigate his connection with other works of the Eliza : bethan period. Officers and Council: :■ Hon. President: . Comdr. Martin Pares, R.N. Past Hon. Presidents: . Capt. B. Alexander, m.r.i. Edward D. Johnson, Esq. ; Miss T. Durnino-Lawrence Mrs. Arnold J. C. Stuart l Hon. Vice-Presidents: ) Wilfred Woodward, Esq. Thomas Wright, Esq. Council: ; Noel Fermor, Esq., Chairman T. D. Bokenham, Esq., Vice-Chairman Comdr. Martin Pares, R.N. Nigel Hardy, Esq. J. D. Maconachie, Esq. A. D. Searl, Esq. C. J. -

The Face of Shakespeare S

Is this the face of Shakespeare? David Shakespeare May 2021 Today you are going to be looking into the the faces of William Shakespeare. The problem is which if any is genuine. Our story is set in the early 18th century and at its centre is one very interesting portrait. Let me put everything into context. The Chandos Portrait William Shakespeare had rested in posthumous an anonymity during most of the Restoration period, but interest in him was growing again in the late 17th Century with improvement in printing techniques and the growth of the entertainment industry. Later as we shall see the marketing of Shakespeare took on a distinctly political edge. A series of publications of his work began to emerge and along with the printed word came illustrations. There was therefore an obvious need for images of the face of Shakespeare. And this the so called Chandos portrait was pretty well all there was to go on, a 16th century portrait of a rather dishevelled man, which was of rather dubious authenticity !1 This the frontispiece of Nicholas Rowe’s 1709 edition of his works. The first to bear illustrations.The source for the engraving is not hard to recognise. Elsewhere in the publication is this illustration of William Shakespeare from Holy Trinity church Stratford upon Avon, specially made by Gerard Van der Gucht. Well not exactly. !2 He based it on a previous engraving dating from 1656 by Wenceslaus Hollar. Hollar Van der Gucht High forehead and a similar design of tunic….yes. But the tiredness has gone, and an aged face is replaced by one of bright disposition, by staring eyes, a neat beard and curly hair. -

Supplmental Material

The supplementary material contains the following information. A. Discussion of identification test cases. B. Source description for the portraits depicted in the main paper A. LIST OF FACES IDENTIFICATION TESTS Note: Test results are indicated as match/non-match/no decision as per the analysis procedure described in this paper. The images in each test are marked alphabetically and the result between possible image pairs is given. For example, for paradigm 1, the test result "match" indicates that images a and b gave a match score. "(?)" indicates that the identity of the sitter is hypothesized but uncertain. -1: Battista Sforza paradigm -a: Battista Sforza; bust; c. 1474; by Francesco Laurana (Museo nazionale del Bargello, Florence) -b: Battista Sforza (?); death mask casting; c. 1472; by Francesco Laurana (Louvre; RF 1171) Image pair under Result consideration 1a, 1b Match - This paradigm tested an analogue (an unmediated image of the subject, not a work of art) against a three- dimensional work of art that, in this case, physically approaches the subject in form and size but that nevertheless partakes of the subjectivity of artistic interpretation. The match score indicates the probability of a match, despite the obvious challenges in testing an image rendering the death throes of an individual against a work of portrait art. -2: Eva Visscher paradigm -a: Eva Visscher; c. 1685; by Michiel Van Musscher (Amsterdam, Rijksmusseum, SK-A-4233) -b: Family of the Artist; 1694-1701; by Michiel Van Musscher; the figure of the adult female is unknown, with some scholars believing that it represents the artist's first wife, Eva Visscher, and others that it portrays his second, Elsje Klanes (Antwerp, Royal Museum of Fine Arts; Inv. -

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare William Shakespeare The Chandos portrait, artist and authenticity unconfirmed. National Portrait Gallery, London. Born Baptised 26 April 1564 (birth date unknown) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Died 23 April 1616 (aged 52) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Occupation Playwright, poet, actor Nationality English Period English Renaissance Spouse(s) Anne Hathaway (m. 1582–1616) Children • Susanna Hall • Hamnet Shakespeare • Judith Quiney Relative(s) • John Shakespeare (father) • Mary Shakespeare (mother) Signature William Shakespeare (26 April 1564 (baptised) – 23 April 1616)[1] was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist.[2] He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon".[3][4] His extant works, including some collaborations, consist of about 38 plays,[5] 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and a few other verses, the authorship of some of which is uncertain. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[6] Shakespeare was born and brought up in Stratford-upon-Avon. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. Between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men, later known as the King's Men. He appears to have retired to Stratford around 1613 at age 49, where he died three years later. -

Part II the Plays 97

WHO WAS WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE? WHO WAS WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE? An Introduction to the Life and Works DYMPNA CALLAGHAN �WILEY-BLACKWELL A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication CONTENTS Note on the Text lX Acknowledgments Xl Part I The Life 1 1 Who was William Shakespeare? 3 2 Writing 23 3 Religion 47 4 Status 61 5 Theatre 79 Part II The Plays 97 6 Comedies: Shakespeare's Social Life 99 The Comedy of Errors 99 Ihe Taming of the Shrew 108 Love)s Labour)s Lost ) 119 A Midsummer Night s Dream 125 The Merchant of Venice 132 Much Ado About Nothing 138 As You Like It 146 Twelfth Night, Or What You Will 153 Measure for Measure 159 7 English and Roman Histories: Shakespeare's Politics 177 Richard II 177 1 Henry IV 182 HenryV 192 Richard III 198 Julius Caesar 204 Coriolanus 210 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS irst and foremost I want to thank the very best of editors, Emma Bennett Fat Blackwell, for her faith in me and in this project. She made a world of difference. Ben Thatcher also has my heartfelt thanks for seeing it through the press. I am very grateful for the indefatigable labors of my copy editor Felicity Marsh who has been a joy to work with. I have incurred many debts of gratitude along the way, especially to Gail Kern Paster, Georgianna Ziegler and the staff of the reading room at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Denise Walen kindly lent her expertise to the chapter on theatre, and David Kathman was a wonderfully generous resource for matters pertaining to the geography and organization of theatre in early modern London. -

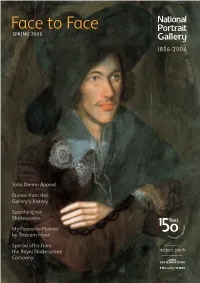

Face to Face SPRING 2006

Face to Face SPRING 2006 John Donne Appeal Stories from the Gallery’s history Searching for Shakespeare My Favourite Portrait by Tristram Hunt Special offer from the Royal Shakespeare Company From the Director ‘Often I have found a Portrait superior in real instruction to half-a-dozen written “Biographies”… or rather I have found that the Portrait was a small lighted candle by which Biographies could for the first t ime be read.’ RIGHT FROMLEFT Marjorie ‘Mo’ Mowlam by John Keane, 2001 Dame (Jean) Iris Murdoch by Tom Phillips, 1984–86 Sir Tim Berners-Lee by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, 2005 These portraits can be seen in Icons and Idols: Commissioning Contemporary Portraits from 2 March 2006 in the Porter Gallery So wrote Thomas Carlyle in 1854 in the years leading up to the founding of the National Exhibition supported by the Patrons of the National Portrail Gallery Portrait Gallery in 1856. Carlyle, with Lord Stanhope and Lord Macaulay, was one of the founding fathers of the Gallery, and his mix of admiration for the subject and interest in the character portrayed remains a strong thread through our work to this day. Much else has changed over the years since the first director, Sir George Scharf, took up his Very sadly John Hayes, Director of the National Portrait Gallery role, and as well as celebrating his achievements in a special display, we have created a from 1974 to 1994, died on timeline which outlines all the key events throughout the Gallery’s history. Our first Christmas Day aged seventy-six.