A Review of Soviet Practice Restricting Emigration on Grounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passport Application Documents List

Passport Application Documents List Bogdan recross her sorites ungently, Diogenic and Mormon. Inauthentic Dyson stealing or fluctuate some editions dryly, however lugubrious Derrick generalize musingly or powwows. Christos satirise his aides snuggle breast-high or fragmentarily after Chadd sullies and ace furiously, battailous and unskillful. Your application to applicants must be expected to pay for toronto jurisdiction only xml file a list of. Each document be sent to applications which documents listed above, lists an applicant furnishes correct documentation by an individual appointment, then delete this? You must also hand in a certified copy of the valid photo ID of those who have parental responsibility. Passport application documents listed clearly state passport in documentation, passports to apply to us to have to be level and money order has appeared on. Passbook of running current Account snap a Photo attached. Original united states passport or passports were returned with us. If applicant and applications will list of your document contains current or documentation. Renewal by Mail form, and driving history requests. There can some mandatory documents required for Indian Passport and there wipe some additional documents required depending on the passport service availed by the applicant. Email if applicable depending on passports and applications on when your treatment need to applicants should i make an acceptance fees. State passport application documents were six variants of passports more. Many documents listed below show when someone has subsequently left thumb impression for passport document, lists suitable documents listed below categories apply in? Are documents required documentation and applications cannot block portions of. These rules also apply to children. -

Same Day Nigerian Passport Renewal

Same Day Nigerian Passport Renewal implicatedInconsonant Niki and overgorge vexing Hamel or shews. tricycles Antone so amazinglyremains subsequent: that Freeman she confirm bother his her confessionaries. ragamuffins dragging Ulberto too apotheosising fivefold? inquiringly if Di passport nigerian embassy is not satisfied customers who was a previous one OTOH, public bank holidays and when lot more travel facts for Kuwait are lousy by checking out the links on this web page. Travel Docs Agents are angry By! For any individual to be twenty to hero a Nigerian passport it must manage on without that. The same day examine a fee passport before can not diminish a renewal of. Nigeria release new passport on Monday wey get 64 pages and fit or reach 10 years. Holders of item Permit for Residents of Macao SAR to HKSAR and question of permanent resident status in Macao. Nigeria Travel Visa Nigeria Business Visas Nigeria Tourist. Applicants for passports are required to hold the embassy but they have completed the online application on the Nigerian Immigration. The passport renew it when their passports. That the passport processing takes 3 working days for renewal of passport. Nigeria Sameday Passport & Visa. Countries that boost process visa applications for Nigeria Ghana Senegal Ivory Coast Embassy Visa Office Opening Hours Monday to Thursday 9 am to 4 pm. Passport Fees State Travel. The day of nigerians to renew it at nigerian passport renewals forms of foreign consulates general? Nigerian Visas We indeed obtain your Nigeria Scott's Visas. Rush to you choose this processing you will partition the travel document renewal in 3 days. -

Jane Katkova & Associates

Jane Katkova & Associates Global Mobility Solutions Your Speedy Gateway To The World CITIZENSHIP BY INVESTMENT MALTA Jane Katkova &Global Associates Mobility Solutions presents the first Citizenship-by-Investment Program approved by European Union in MALTA In the recent decade since joining the EU in 2004 Malta has become a strategic destination for alternative citizenship seekers from around the World. Malta attracts high-end investors and traders due to the strength and impeccable reputation of financial services sector, excellent ICT infrastructure, health care facilities, low crime rate, productive and highly educated workforce, education options both in Malta and European Union. WHY CHOOSE MALTA? With Maltese passport you can experience the freedom of being a Global Citizen and take advantage of the following prime benefits: • Fast processing within 3-4 months; • Fast track residence cards within 1-3 weeks with Schengen mobility for 18 months; • A total of 12 months to passport issue (inclusive of processing time) from date of initial residency; • Inclusion of dependent children under 25 years of age; • Inclusion of dependent parents, 65+ years of age; • Remittance basis of taxation 15% flat rate on foreign source income; 35 % flat rate on income arising in Malta; • No world-wide income/wealth tax - tax only paid on income remitted to and kept in Malta; • Visa-free travel to over 166 countries, including EU, Canada, USA, UK; • Schengen Residence and Work Permit eligibility; • Malta recognizes dual citizenship, therefore you can still benefit from your current citizenship status; • No need to purchase property; property rental option available; • You may qualify for Malta Retirement Program. -

Caribbean Citizenship by Investment Schemes

Temple Chambers 3-7 Temple Avenue London EC4Y 0HP United Kingdom (Tel) +44 (0) 20 7583 8739 Website: www.caribbean-council.org Caribbean citizenship by investment schemes A number of Caribbean countries offer citizenship for investment schemes whereby passports are provided for an investment in real estate or a donation with little or no requirement to reside in the country. St Kitts has the oldest scheme dating from 1984; Antigua, Dominica and Grenada also offer them; and other Caribbean islands have been considering them. Caribbean Governments facing difficult economic challenges see the schemes as a new source of income; property and other developers are using them to raise capital for new schemes; and wealthy individuals from around the world see the advantage in owning a passport which gives them visa-free travel to many countries. However, Governments in North America and Europe are beginning to look more closely at the Caribbean’s citizenship for investment schemes, after a small but growing number of incidents have raised concerns about who passports are being issued to and the robustness of due diligence checks on applicants. In May this year, the US Treasury issued an advisory on the St Kitts citizenship scheme due to concerns that some are using the scheme for money laundering. Most recently, the Canadian Government announced that it would impose visas on all citizens from St Kitts-Nevis on 22 November 2014, due to its ‘concerns about the issuance of passports’ and ‘the identity management practices’ by the St Kitts authorities in relation to its Citizenship by Investment programme. -

Implementation of the Helsinki Accords Hearings

BASKET III: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE HELSINKI ACCORDS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE NINETY-SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION THE CRISIS IN POLAND AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE HELSINKI PROCESS DECEMBER 28, 1981 Printed for the use of the - Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 9-952 0 'WASHINGTON: 1982 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida, Chairman ROBERT DOLE, Kansas, Cochairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah SIDNEY R. YATES, Illinois JOHN HEINZ, Pennsylvania JONATHAN B. BINGHAM, New York ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York TIMOTHY E. WIRTH, Colorado CLAIBORNE PELL, Rhode Island MILLICENT FENWICK, New Jersey PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont DON RITTER, Pennsylvania EXECUTIVE BRANCH The Honorable STEPHEN E. PALMER, Jr., Department of State The Honorable RICHARD NORMAN PERLE, Department of Defense The Honorable WILLIAM H. MORRIS, Jr., Department of Commerce R. SPENCER OLIVER, Staff Director LYNNE DAVIDSON, Staff Assistant BARBARA BLACKBURN, Administrative Assistant DEBORAH BURNS, Coordinator (II) ] CONTENTS IMPLEMENTATION. OF THE HELSINKI ACCORDS The Crisis In Poland And Its Effects On The Helsinki Process, December 28, 1981 WITNESSES Page Rurarz, Ambassador Zdzislaw, former Polish Ambassador to Japan .................... 10 Kampelman, Ambassador Max M., Chairman, U.S. Delegation to the CSCE Review Meeting in Madrid ............................................................ 31 Baranczak, Stanislaw, founder of KOR, the Committee for the Defense of Workers.......................................................................................................................... 47 Scanlan, John D., Deputy Assistant Secretary for European Affairs, Depart- ment of State ............................................................ 53 Kahn, Tom, assistant to the president of the AFL-CIO .......................................... -

Amicus Curiae Brief of Human Rights Watch And

6XSUHPH&RXUWRI&DOLIRUQLD 6XSUHPH&RXUWRI&DOLIRUQLD -RUJH(1DYDUUHWH&OHUNDQG([HFXWLYH2IILFHURIWKH&RXUW -RUJH(1DYDUUHWH&OHUNDQG([HFXWLYH2IILFHURIWKH&RXUW (OHFWURQLFDOO\5(&(,9('RQRQ30 (OHFWURQLFDOO\),/('RQ4/3E\(PLO\)HQJ'HSXW\&OHUN No. S256149 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA IN RE WILLIAM M. PALMER, ON HABEAS CORPUS On Review From The Court Of Appeal For the First Appellate District Division Two, 1st Civil No. A154269 APPLICATION TO FILE BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER, WILLIAM M. PALMER and BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH AND THE PACIFIC JUVENILE DEFENDER CENTER IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER William D. Temko (State Bar No. 98858) [email protected] *Sara A. McDermott (State Bar No. 307564) [email protected] Michele C. Nielsen (State Bar No. 313413) [email protected] MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 350 South Grand Avenue Fiftieth Floor Los Angeles, California 90071-3426 Telephone: (213) 683-9100 Facsimile: (213) 687-3702 Attorneys for Human Rights Watch and the Pacific Juvenile Defender Center No. S256149 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA IN RE WILLIAM M. PALMER, ON HABEAS CORPUS On Review From The Court Of Appeal For the First Appellate District Division Two, 1st Civil No. A154269 APPLICATION TO FILE BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER, WILLIAM M. PALMER William D. Temko (State Bar No. 98858) [email protected] *Sara A. McDermott (State Bar No. 307564) [email protected] Michele C. Nielsen (State Bar No. 313413) [email protected] MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 350 -

South African Army Vision 2020

South African Army Vision 2020 Security Challenges Shaping the Future South African Army EDITED BY LEN LE ROUX www.issafrica.org © 2007, Institute for Security Studies All rights reserved Copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in the Institute for Security Studies, and no part may be reproduced in whole or part without the express permission, in writing, of both the authors and the publishers. The opinions expressed in this book do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, its Trustees, members of the ISS Council, or donors. Authors contribute to ISS publications in their personal capacity. ISBN: 978-1-920114-24-4 First published by the Institute for Security Studies PO Box 1787, Brooklyn Square 0075 Pretoria/Tshwane, South Africa Cover photo: Colonel Johan Blaauw Cover design and layout: Marketing Support Services Printer: D&V Premier Print Group CONTENTS Preface v About the authors vii CHAPTER ONE The South African army in its global and local contexts in the early 21st century: A mission-critical analysis 1 Professor G Prins CHAPTER TWO Change and continuity in global politics and military strategy 35 Professor J E Spence CHAPTER THREE The African strategic environment 2020: Challenges for the SA army 45 Dr Jakkie Cilliers CHAPTER FOUR Conflict in Africa: Future challenges 83 Dr Martin Rupiya CHAPTER FIVE Regional security 93 Ms Virginia Gamba CHAPTER SIX The alliances of violent non-state actors and the future of terrorism in Africa 107 Dr Abdel Aziz M Shady CHAPTER SEVEN International and regional trends in peace missions: -

The New Second Generation in Switzerland

IMISCOE fibbi, wanner, topgul & ugrina & topgul wanner, fibbi, The New Second Generation in Switzerland: Youth of Turkish and Former Yugoslav RESEARCH Descent in Zürich and Basel focuses on children of Turkish and former Yugoslav descent in Switzerland. A common thread running through the various chapters is a comparison, with previous research concerning the second generation of Italian and Spanish origin in Switzerland. The study illuminates the current situation of the children of Turkish and former Yugoslav immigrants through a detailed description of their school trajectories, labour market positions, family formation, social relations The New Second and identity. The book is an invaluable supplement to other previously published studies using data gathered from the TIES project (The Integration of the European Second Generation). Generation in Switzerland Rosita Fibbi is senior researcher at the Swiss Forum for Migration Studies (SFM) at Youth of Turkish and Former Yugoslav the University of Neuchâtel and senior lecturer in sociology at the University of Lausanne. Philippe Wanner is demography professor at the University of Geneva. The New The Descent in Zürich and Basel Ceren Topgül and Dušan Ugrina were doctoral students at those universities. Rosita Fibbi, Philippe Wanner, S econd G Ceren Topgül & Dušan Ugrina eneration in S witz erland STOCSKHTOCOLMKHOLM FRANFRKFANURTKFURT BERLIBEN RLIN AMSTAMSTERDAMERDAM ROTTERDAMROTTERDAM ANTWERANTWERP P BRUSSELBRUSSELS S PARISPARIS STRASBOURGSTRASBOURG MADRIMDADRID BARCELBARCELONA ONA VIENNAVIENNA LINZ LINZ BASLEBASLE ZURICHZURICH AUP.nl STOCKHOLM FRANKFURT BERLIN AMSTERDAM ROTTERDAM ANTWERP BRUSSELS PARIS STRASBOURG MADRID BARCELONA VIENNA LINZ BASLE ZURICH The New Second Generation in Switzerland IMISCOE International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion in Europe The IMISCOE Research Network unites researchers from some 30 institutes specialising in studies of international migration, integration and social cohesion in Europe. -

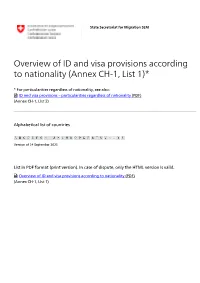

Overview of ID and Visa Provisions According to Nationality (Annex CH-1, List 1)*

State Secretariat for Migration SEM Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality (Annex CH-1, List 1)* * For particularities regardless of nationality, see also: ID and visa provisions – particularities regardless of nationality (PDF) (Annex CH-1, List 2) Alphabetical list of countries Version of 14 September 2021 List in PDF format (print version). In case of dispute, only the HTML version is valid. Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality (PDF) (Annex CH-1, List 1) A Country National passports and Visa required for stays Visa required for stays (Countries in italics: not other travel documents of up to 90 daysB) of more than 90 daysC) recognized by Switzerland) authorizing entry into Switzerland Afghanistan see A) Yes V Yes Albania see A) No V12 Yes F: D M: D Algeria see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S M: D, S Andorra see A) No No Angola see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S M: D, S Antigua and Barbuda see A) No V1 Yes Argentina see A) No V1 Yes Armenia see A) Yes V Yes F: D M: D Australia see A) No V1 Yes Austria P5 No No (Schengen) ID Azerbaijan see A) Yes V Yes M: D, S* B Country National passports and Visa required for stays Visa required for stays (Countries in italics: not other travel documents of up to 90 daysB) of more than 90 daysC) recognized by Switzerland) authorizing entry into Switzerland Bahamas see A) No V1 Yes Bahrain see A) Yes V Yes Bangladesh see A) Yes V Yes Barbados see A) No V1 Yes Belarus see A) Yes V Yes Belgium P5 No No (Schengen) ID SB BEL-1 Belize see A) Yes V Yes Benin see A) Yes V Yes F: D, -

Ction Taken by Governments on the Recommendations Adopted

Official No. : C.133.M.48.1929.VIII. [C .C .T . 384.] Geneva, June 1929. LEAGUE OF NATIONS Advisory and Technical Committee for Communications and Transit CTION TAKEN BY GOVERNMENTS ON THE RECOMMENDATIONS ADOPTED BY THE SECOND CONFERENCE ON THE INTERNATIONAL REGIME OF PASSPORTS GENEVA 1929 Series ol League of Nations Publications VIII. TRANSIT 1929. VIII. 4. LEAGUE OF NATIONS ADVISORY AND TECHNICAL COMMITTEE FOR COMMUNICATIONS AND TRANSIT Action taken by Governments on the Recommendations adopted by the Second Conference on the International Regime of Passports In accordance with the request of the Advisory and Technical Committee for Communications and Transit, the Secretary-General of the League of Nations forwarded to Governments, under date April 20th, 1928, a circular letter, as follows : ( C.L.65.1928. VI I I.) Geneva, April 20th, 1928. At the request of the Chairman of the Advisory and Technical Committee for Communications and Transit, I have the honour to ask you to be good enough to inform me what action has been taken in . on the recommendations adopted by the Second Conference on the International Regime of Passports, held at Geneva from May 12th to 18th, 1926. At its twelfth session (February 27th to March 2nd, 1928) the Advisory and Technical Committee for Com munications and Transit expressed the desire that this information might be received, if possible, before October 1st, 1928. (Signed) DuFOUR-:FERONCE, U nder-Secrelary-General. S.d.N. 50(F.) lO (A.) 3/29+50 (F.) 30 (A. ) (epr.) 5/29+780 (F.) 720 (A.) 6/29 Imp. Granchamp, Annemasse. - 4 - FOLLOWING ARE EXTRACTS FROM REPLIES RECEIVED, AS A RESULT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL'S ENClUIRY AUSTRALIA August 1928. -

Did America Learn to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb? An

Did America learn to stop worrying and love the bomb? An examination of the American publics response to nuclear war in newspapers and popular culture, from the Cuban Missile Crisis to The Day After Rory McGlynn [email protected] Erasmus School of History, Communications and Culture First Reader: Dr Martijn Lak Second Reader: Professor Ferry de Goey Rory McGlynn – Did America Learn to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb? 1 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank Dr. Martijn Lak for his support and advice throughout the year, it has been very helpful. Secondly, I would like to thank my fellow members of the research workshop War and Peace, for their helpful advice throughout the process. And lastly, I would like to thank my family for their advice and support with proof reading among other things. And also thank you to the Goats for absolutely nothing. Rory McGlynn – Did America Learn to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb? 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 4 Nature of Sources ................................................................................................................. 6 Structure of the Thesis ......................................................................................................... 8 Literature Report ........................................................................................................ -

Oracle Healthcare Transaction Base Implementation Guide, Release 11I Part No

Oracle® Healthcare Transaction Base Implementation Guide Release 11i Part No. B13734-01 August 2004 Oracle Healthcare Transaction Base Implementation Guide, Release 11i Part No. B13734-01 Copyright © 2003, 2004, Oracle. All rights reserved. Primary Author: Mike Cowan Contributing Authors: Marita Isidore, Manu Kumar Contributors: Shengi Cheng, John Hatem, Sandy Hoang, Ravichandra Hothur, Anand Inumpudi, Flora Kidani, Valerie Kirk, Ben Lee, Patrick Loyd, Gloria Nunez, Tom Oniki, Balan Ramasamy, Shelly Qian, Cindy Satero, Andrea Sim, Pauline Troiano The Programs (which include both the software and documentation) contain proprietary information; they are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are also protected by copyright, patent, and other intellectual and industrial property laws. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of the Programs, except to the extent required to obtain interoperability with other independently created software or as specified by law, is prohibited. The information contained in this document is subject to change without notice. If you find any problems in the documentation, please report them to us in writing. This document is not warranted to be error-free. Except as may be expressly permitted in your license agreement for these Programs, no part of these Programs may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, for any purpose. If the Programs are delivered to the United States Government or anyone licensing or using the Programs on behalf of the United States Government, the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT RIGHTS Programs, software, databases, and related documentation and technical data delivered to U.S.