Teaching Math in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steven Mwesigwa : Portfolio

Email [email protected] Address Kisaasi, Kampala, Uganda. Phone +256 757 007131 +256 788 702021 Portfolio https://steven7mwesigwa.github.io/ Steven Mwesigwa Twitter https://twitter.com/steven7mwesigwa OBJECTIVE To advance, challenge and be challenged in a dynamic opportunity that contributes to outstanding organisational success and reputation. I seek to diversify and enhance my skills in the industry and as part of a larger organisation. EXPERIENCE Freelance Web Developer Sole proprietor -Built custom websites from scratch. Kampala Central -Improved my workflows. December-2017-Currently Digital Marketer Sole proprietor -Marketed content of an upcoming music artist Kampala Central using social media. February-2017-October-2017 EDUCATION Diploma in Civil and Building Engineering -Learnt about construction plans, quantification of Kyambogo University building materials, construction process, etc Kampala- Uganda -CGPA 3.93 2012-2014 Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education -Obtained 17 points in the combination of Physics, Mengo Senior School Chemistry, Mathematics and Entrepreneurship Kampala- Uganda 2010-2011 Uganda Certificate of Education Mengo Senior School -Obtained 15 aggregates in best eight subjects; with Kampala-Uganda three D1s, three D2s and two C3s 2006-2009 SKILLS Languages: Java, JavaScript (prior experience), PHP (prior experience) Other Skills: Wordpress, MySQL, Network+, Linux+, jQuery, HTML5, CSS3 LANGUAGES Luganda English Fluent at both Oral and Written Fluent at both Oral and Written HONOURS & AWARDS -Google : https://learndigital.withgoogle.com/digitalskills Awarded Fundamentals Of Digital Marketing Certification. Gained knowledge of all things digital, from websites and tracking to online marketing and beyond. I discovered how to attract new customers by optimising the business's digital presence on Google, learnt how to gather consumer insights, discovered tools to make a business succeed, and getting started with online advertising. -

Newsletter No

TEAA (Teachers for East Africa Alumni) Newsletter No. 36, January 2017. Please send any changes to your contact information and/or items for the newsletter to Ed Schmidt, 7307 Lindbergh Dr., St. Louis, MO 63117, USA, 314-647-1608, <[email protected]>. In this Issue: Detroit -- TEAA Grand Finale President’s Message, Brooks Goddard On Our Website, Henry Hamburger Next UK reunion, Clive Mann <[email protected]> Recent Emails from East African Head Teachers and Principals Transformation and Continuity in Tanzanian Teacher Education, Fran Vavrus TEAAers Create View from the Eastern Side of the Pond, Richard Price. Your Stories, John Filby and Paul Haslam We’ve Heard from You Obituaries. Byron Birdsall, Johney Brooks, Larry Olds, Leigh Proudfoot, Robert L. Wendel Directory Update DETROIT - TEAA GRAND FINALE August 17-20, 2017 Mark your calendar for a Detroit visit, August 17-20, 2017. Here’s why. Fifty-six years ago, the first of us went to East Africa to teach. We went before the Peace Corps teachers – we are their proud predecessors! More than 600 of us went in the next ten years. In 1999, Ed Schmidt decided to find us all, and in two years he had located more than 400 of us. We are can-do folks. Our first reunion/conference was held in Washington DC only nine days after the 9/11 attacks. About 130 of us came to that stunned city. The Peace Corps had planned its 40th reunion for that same weekend. They cancelled, but we came. In 2015, at the Minneapolis Reunion, TEAAers voted to make the 2017 Reunion our last in-person gathering. -

Why Traditional Schools Excel at Pre-University Entry Exams

COMMENT NEW VISION, Friday, June 5, 2015 13 YOUR VIEW What do you think of these issues in the week? RELIGIOUS DEVOTION Katherine Nabuzale, Ugandan in Germany Uganda is a country with diverse religious denominations. It is captivating to observe how committed and dedicated Ugandans are to their faith but unfortunately Education minister Jessica Alupo receiving examination results from UNEB secretary Matthew Bukenya not the same enthusiasm is accorded to what affects their livelihoods. Why is it so? The Rt. Rev. Dr. Fred Sheldon Mwesigwa Story on www.newvision.co.ug Why traditional schools excel EUROPEAN RECOVERY Thomas Fricke and Xavier Timbeau, Project Syndicate, 2015 at pre-university entry exams In the coming months, European leaders will confront two major challenges. First, they will need to fi nd a way to turn a fragile upturn in ollowing the release of entry exams? While the paradox can be economic conditions into a lasting Makerere University Bachelor explained away using the argument of recovery. Then, they will need of Laws pre-entry exam results Uganda’s education system that promotes to push for real progress in the and its attendant implications, rote learning over holistic education that transition to a low-carbon future, the Ministry of Health centres on the head, heart and hands, ahead of the UN Climate Change and Makerere University there seems to be much more than meets Conference in Paris at the end of FMedical School have opened debate on the eye. the year. the possibility of medical students doing Instead of the Ministry of Health and Full story on www.newvision.co.ug pre-university entry exams, thereby casting medical school authorities making doubt on UNEB as the sine-qua-non of arguments for and against pre-entry university admissions in Uganda. -

Makerere University

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY ESTABLISHMENT OF FEMALE STUDENTS’ PARTICIPATION IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN KAMPALA BY KAMARA ROGERS 16/U/5314/PS KISAKYE VICTO 16/U/6147/PS KUSOLO JULIUS 16/U/489 A RESEARCH REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE, TECHNICAL AND VOCATIONAL EDUCATION IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE WITH EDUCATION (BIOLOGICAL) OF MAKERERE UNIVERSITY AUGUST, 2019 1 DEDICATION We dedicate this research work to our beloved i DECLARATION We, the under signed, do declare that this research report entitled “Establishment of Female Students’ Participation in Physical Activity in Selected Secondary Schools in Kampala” is our original work, except where ideas of other writers and scholars are specifically acknowledged. It has never been presented to any university or institution of high learning for any a degree award or any other awards. NAME REGISTRATION NUMBER SIGNATURE KAMARA ROGERS 16/U/5314/PS KISAKYE VICTO 16/U/6147/PS KUSOLO JULIUS 16/U/489 Date................................................... ii iii APPROVAL iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all those who supported and encouraged us to complete this project report with special thanks to our beloved lecturers at the Department of Science, Technical and Vocational Education, Makerere University for his wisdom, encouragement and remarkable guidance. These include Besweri Wandera (Mr) who supervised this work to the end, Nicholas Elijah Mulabi (Mr), Edward Kansiime (Mr), Dr. Henry Busulwa (PhD), John Mugera (Mr), Dr. Allen Naluggwa (PhD) and Dr. John Sentongo (PhD). We appreciate our classmates the BIO/PE class and the entire Education class of 2018/2019 finalists. -

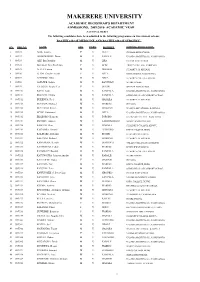

Makerere University

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT ADMISSIONS, 2009/2010 ACADEMIC YEAR NATIONAL MERIT The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme on Government scheme: BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY S/N REG NO NAME SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL/ INSTITUTION 1 09/U/1 AGIK Sandra F U GULU GAYAZA HIGH SCHOOL 2 09/U/2 AHIMIBISIBWE Davis M U KABALE UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 3 09/U/3 AKII Bua Douglas M U LIRA HILTON HIGH SCHOOL 4 09/U/4 AKULLO Pamella Winnie F U APAC TRINITY COLLEGE, NABBINGO 5 09/U/5 ALELE Franco M U DOKOLO ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 6 09/U/6 ALENI Caroline Acidri F U ARUA MT.ST.MARY'S, NAMAGUNGA 7 09/U/7 AMANDU Allan M U ARUA ST MARY'S COLLEGE, KISUBI 8 09/U/8 ASIIMWE Joshua M U KANUNGU NTARE SCHOOL 9 09/U/9 AYAZIKA Kirabo Tess F U BUGIRI GAYAZA HIGH SCHOOL 10 09/U/10 BAYO Louis M U KAMPALA UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 11 09/U/11 BUKAMA Martin M U KAMPALA OLD KAMPALA SECONDARY SCHOOL 12 09/U/12 BUKENYA Fred M U MASAKA ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 13 09/U/13 BUYINZA Michael M U WAKISO DIPLOMA 14 09/U/14 BUYUNGO Steven M U MUKONO NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 15 09/U/15 ECONI Emmanuel M U ARUA UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 16 09/U/16 EKAKORO Kenneth M U TORORO KATIKAMU SEC. SCH., WOBULENZI 17 09/U/17 EMYEDU Andrew M U KABERAMAIDO NAMILYANGO COLLEGE 18 09/U/18 KABUGO Deus M U MASAKA ST HENRY'S COLLEGE, KITOVU 19 09/U/19 KAGAMBA Samuel M U LUWEERO KING'S COLLEGE, BUDO 20 09/U/20 KALINAKI Abubakar M U BUGIRI KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 21 09/U/21 KALUNGI Richard M U MUKONO ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 22 09/U/22 KANANURA Keneth M U BUSHENYI VALLEY COLLEGE SS, BUSHENYI 23 09/U/23 KATEREGGA Fahad M U WAKISO KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 24 09/U/24 KATSIGAZI Ronald M U KAMPALA ST MARY'S COLLEGE, KISUBI 25 09/U/25 KATUNGUKA Johnson Sunday M U KABALE NTARE SCHOOL 26 09/U/26 KATUSIIME Hawa F U MASINDI DIPLOMA 27 09/U/27 KAVUMA Paul M U WAKISO KING'S COLLEGE, BUDO 28 09/U/28 KAVUMA Peter M U KAMPALA OLD KAMPALA SECONDARY SCHOOL 29 09/U/29 KAWUNGEZI S. -

2014 Annual Report

FORUM FOR AFRICAN WOMEN EDUCATIONALISTS UGANDA CHAPTER Annual Programme Report January 2014 – December 2014 Prepared by: Dorothy Muhumure Programmes Manager December 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 3 ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.0 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................... 11 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 11 2.0 ASSESSMENT OF PERFORMANCE FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY – DECEMBER 2014. .. 11 2.1 Policy influence for girl-child education ......................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 Planned targets for the period January 2014 – December 2014. ..................................... 11 2.1.2 Expected outcome for the period January – December 2014 ........................................... 12 2.1.3 Progress of implementation of activities/Achievements ..................................................... 12 2.1.4 Significant unplanned activities implemented -

Makerere University Business School

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY BUSINESS SCHOOL ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT PRIVATE ADMISSIONS, 2018/2019 ACADEMIC YEAR PRIVATE THE FOLLOWING HAVE BEEN ADMITTED TO THE FOLLOWING PROGRAMME ON PRIVATE SCHEME BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING (MUBS) COURSE CODE ACC INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0801/525 NAMIRIMU Carolyne Mirembe 2017 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.8 2 U0083/542 ANKUNDA Crissy 2017 F U 46 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 3 U0956/649 SSALI PAUL 2017 M U 49 NAMIREMBE HILLSIDE S.S. 45.4 4 U0169/626 MUHANUZI Robert 2017 M U 102 ST.ANDREA KAHWA'S COL., HOIMA 45.2 5 U0048/780 NGANDA Nasifu 2017 M U 88 MASAKA SECONDARY SCHOOL 44.5 6 U0178/502 ASHABA Lynn 2017 F U 12 CALTEC ACADEMY, MAKERERE 43.6 7 U0060/583 ATUGONZA Sharon Mwesige 2017 F U 13 TRINITY COLLEGE, NABBINGO 43.6 8 U0763/546 NYALUM Connie 2017 F U 43 BUDDO SEC. SCHOOL 43.3 9 U2546/561 PAKEE PATIENCE 2016 F U 55 PRIDE COLLEGE SCHOOL MPIGI 43.3 10 U0334/612 KYOMUGISHA Rita Mary 2011 F U 55 UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 43.1 11 U0249/532 MUGANGA Diego 2017 M U 55 ST.MARIA GORETTI S.S, KATENDE 42.1 12 U1611/629 AHUURA Baseka Patricia 2017 F U 34 OURLADY OF AFRICA SS NAMILYANGO 41.5 13 U0923/523 NABUUMA MAJOREEN 2017 F U 55 ST KIZITO HIGH SCH., NAMUGONGO 41.5 14 U2823/504 NASSIMBWA Catherine 2017 F U 55 ST. HENRY'S COLLEGE MBALWA 41.3 15 U1609/511 LUBANGAKENE Innocent 2017 M U 27 NAALYA SSS 41.3 16 U0417/569 LUBAYA Racheal 2017 F U 16 LUZIRA S.S.S. -

Bachelor of Science in Software Engineering

BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN SOFTWARE ENGINEERING COURSE CODE BSW INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY SCHOOL 1 U0068/571 KATIRIMA Allan Phene Junior 2010 M U NTARE SCHOOL 2 U0956/965 SEMATIKO Douglas 2010 M U NAMIREMBE HILLSIDE S.S. 3 U1224/590 JUUKO Marvin 2010 M U ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 4 U0459/658 EKINAMUSHABIRE Preciou 2010 M U KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 5 U0068/562 BYAMUGISHA Innocent 2010 M U NTARE SCHOOL 6 U0334/620 MUWONGE Bright Hosea 2010 M U UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 7 U0068/585 MATSIKO Grace 2010 M U NTARE SCHOOL 8 U1223/634 NAMUTEBI Veronica 2010 F U SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 9 U0763/806 MUGISA Nicholas 2010 M U BUDDO SEC. SCHOOL 10 U0334/554 NAMPOGO Adrian Mwota 2010 M U UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 11 U0063/552 NAKAYENGA Catherine 2010 F U MT.ST.MARY'S, NAMAGUNGA 12 U0956/960 MUGYENYI Martin 2010 M U NAMIREMBE HILLSIDE S.S. 13 U1085/517 AYESIGA Agnes 2010 F U BP CYPRIAN KIHANGIRE SS LUZIRA 14 U0794/590 ARINAITWE Tumusiime Bryan 2010 M U GREENHILL ACADEMY, KAMPALA 15 U0004/556 NAKALEMBE Margaret 2010 F U KING'S COLLEGE, BUDO 16 U1379/694 SSEGUJJA Conrad Micheal 2010 M U LUGAZI MIXED SEC. SCH. 17 U0082/579 NDYAMUHAKI Joseph 2010 M U ST.KAGGWA BUSHENYI HIGH SCH. 18 U1509/547 NALWADDA Dorothy 2010 F U COMPREHENSIVE COLLEGE KITETIKKA 19 U1224/813 OPIYO Brian Lamtoo 2010 M U ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 20 U0387/548 LUBEGA Edrin Evarest 2010 M U ST.PETER'S S S, NSAMBYA 21 U0068/607 NAHAMYA Colins 2010 M U NTARE SCHOOL 22 U0064/521 KABENGE Shem 2010 M U NAMILYANGO COLLEGE 23 U0064/502 AINOMUGISHA Solomon 2010 M U NAMILYANGO COLLEGE 24 U0459/694 NANKABIRWA Namusisi Linda 2010 F U KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 25 U0030/709 MUBAZI Eric John 2010 M U KITANTE HILL SCHOOL 26 U0041/998 NANZIRI Bonita Beatrice 2010 F U LUBIRI SECONDARY SCHOOL 27 U0043/686 MUHEREZA Nicholas 2010 M U MAKERERE COLLEGE SCHOOL 28 U2339/533 SEBAGALA Charles 2010 M U ST. -

CRE O LEVEL.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS MAJOR THEME 1: MAN IN A CHANCHING SOCIETY SUB – THEMES: LIVING IN A CHANGING SOCIETY …………………. 2 WORKING IN A CHANGING SOCIETY ……………… 29 LEISURE IN A CHANGING SOCIETY ………………… 46 MAJOR THEME 2: ORDER AND FREEDOM IN SOCIETY SUB – THEMES: JUSTICE IN SOCIETY ……………………….…………. 65 SERVICE IN SOCIETY ………………………….……… 87 LOYALTY TO SOCIETY ………………….…………… 108 MAJOR THEME 3: LIFE SUB – THEMES: HAPPINESS ……………………………….……………. 125 UNENDING LIFE ……………………….……………… 144 SUCCESS ………………………….……..………………161 MAJOR THEME 4: MAN AND WOMAN SUB – THEMES: FAMILY LIFE ………….…………………….…………. 174 SEX DIFFERENCES AND THE PERSON ……………. 194 COURTISHIP AND MARRIAGE ………………….…… 210 MAJOR THEME 5: MAN’S RESPONSE TO GOD THROUGH FAITH AND LOVE SUB – THEMES: MAN’S QUEST FOR GOD ………….………………… 238 MAN’S EVASION OF GOD ………………….………… 255 CHRISTIAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE WORLD ……… 270 1 LIVING IN A CHANGING SOCIETY. What is change? The word change can be used to mean the following: Making something or a situation appear difference from its original stage. This may be positive or negative. Change means altering the state or quality of something or a situation form what it originally used to be. It is to bring a difference in something, a situation or someone either positively or negatively. Change involves something entering a new phase which may either be positive or negative. Change is a fact of life or a reality that can never be avoided. It is irresistible and therefore one is forced to accept to it. Quite often, any change comes with a new experience. This requires that one must make choice either to accept or reject the change. Positive changes are always accepted and they tend to bring joy to the people. -

Sanyu Babies Home

Sanyu Babies’ Home Quarterly Newsletter – Issue 35– April – June, 2017 IN THIS ISSUE Letter from the Chairman Letter from the Director Hello’s & Goodbye’s The Passing of Cyrus Byakatonda Update on Moses Perimeter wall Adoptions New Cots Trip to Freedom City Children’s park Volunteer Report Interview with the Interns Volunteer Opportunities Sponsor A Child Donations Needed How to Donate Donors this quarter LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN It is difficult to find words that are good enough to convey the inner (real) sentimental feelings and emotions one gets when you come face-to-face with the reality in Sanyu Babies’ Home (SBH). You see so many babies with yearning eyes; with the quest for a belonging; you note the open welcome; the constant child innocence; you feel the uncertainty and craving for answers from many toddler faces. Sometime one can be reduced to tears. In this Newsletter, a lot of the agony and traumatic experiences these abandoned vulnerable babies and children have had to endure by being abandoned/orphaned has been reflected. We continue to thank SBH many supporters, donors, volunteers, friends, guardians, foster and adoptive families who have continuously come out to help. We also thank the Bishop of Namirembe Diocese, The Rt. Rev. Wilberforce Kityo Luwalira and the entire Diocese for their overwhelming support. In a special way, the Board of Governors of SBH have extended their appreciation to the special group of donors listed by the Director. Sanyu Babies’ Home, P.O. Box 14162, Mengo, Kampala, Uganda Tel: +256 414 274 032 Mobile+256 712 370 950/ +256 705 681 603 Email: [email protected] Website: www.sanyubabies.com “Let us not become weary in doing good, for at the proper time, we shall reap a harvest if we do not give up” (Galatians 6:9) On top of the continuous endeavor to improve management of the Home; We should recognize that SBH has now a fully-fledged development programme. -

Enews COLLEGE of ENGINEERING, DESIGN, ART & TECHNOLOGY Vol

October - December 2012 CEDAT enews COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, DESIGN, ART & TECHNOLOGY Vol. 2 Issue No. Two successful PhD defences on same day INSIDE On Wednesday 7th November 2012, two members of Staff from the College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology, Mr. Charles Otine and Ms. Lydia Mazzi Kayondo successfully defended their PhD research theses. Dr. Kayondo defended her PhD research thesis, The second annual CEDAT Open Day entitled Geographical Information Technologies – Decision Support for Road Maintenance in Uganda at 9:00 am in the CEDAT conference hall while Dr. Otine defended his research Thesis entitled HIV Patient Monitoring Framework through Knowledge Engineering HIV Patient Monitoring Framework through Knowledge Dr. Lydia Mazzi Kayondo Engineering at 2:00 pm at the same venue. NCC Conference ends successfully The Management and Staff of the College of Profile: Find out who we Engineering, Design, Art and Technology are profiling would like to extend their congratulations to this month both members of staff on this great achievement and wishes them the very best in their careers as well. Kudos to you, Dr. Lydia Mazzi Kayondo and Dr. Charles Otine! Dr. Charles Otine Promotions! Dr. Charles Niwagaba, the Chair, Depart- ment of Civil and Environmental Engineering was on November 29th 2012 promoted to the Minister graces CEDAT annual Presidential Initiative workshop rank of senior lecturer. The CEDAT community Congratulates Dr. Niwagaba upon his promotion. The success you have achieved, is the success Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year you truly deserved. May you meet more glory to the CEDAT family in your life a head. -

Kyambogo University National Merit Admission 2019-2020

KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE COURSE CODE AFD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U1223/539 BALABYE Alice Esther 2018 F U 16 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.9 2 U1223/589 NANYONJO Jovia 2018 F U 85 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.7 3 U0801/501 NAKIMBUGE Kevin 2018 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.9 4 U1688/510 TUMWESIGE Hilda Sylivia 2018 F U 34 KYADONDO SS 45.8 5 U1224/536 AKELLO Jovine 2018 F U 31 ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 45.8 6 U0083/693 TUKASHABA Catherine 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 7 U1609/503 OTHIENO Tophil 2018 M U 54 NAALYA SSS 45.7 8 U0046/508 ATUHAIRE Comfort 2018 F U 123 MARYHILL HIGH SCHOOL 45.6 9 U2236/598 NABULO Gorret 2018 F U 52 ST.MARY'S COLLEGE, LUGAZI 45.6 10 U0083/541 BEINOMUGISHA Izabera 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.5 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF VOCATIONAL STUDIES IN AGRICULTURE WITH EDUCATION COURSE CODE AGD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0059/548 SSEGUJJA Emmanuel 2018 M U 97 BUSOGA COLLEGE, MWIRI 33.2 2 U1343/504 AKOLEBIRUNGI Cecilia 2018 F U 30 AVE MARIA SECONDARY SCHOOL 31.7 3 U3297/619 KIYIMBA Nasser 2018 M U 51 BULOBA ROYAL COLLEGE 31.4 4 U1476/577 KIRYA Brian 2018 M U 93 RAINBOW HIGH SCHOOL, BUDAKA 31.2 5 U0077/619 KIZITO