Does Women's Participation in the National Solidarity Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WKW Creating-New-Spaces-Afghanistan

Women’s Participation in Community Decision-Making Spaces in Afghanistan A Case of Istalif and Kalakan Districts in Kabul Province 2 Women’s Participation in Community Decision-Making Spaces in Afghanistan Acknowledgements Author: Mariam Jalalzada Contributing Partner Organisation: Afghan Women’s Resource Center (AWRC) Design: Dacors Design This research study was made possible by the efforts of the programme staff of the Afghan Women’s Resource Center in Kalakan and Istalif Districts of Kabul Province – especially Samira Aslamzada. Their efforts in organising the field trips, focus group discussions with the women, and interviews with various individuals, is to be lauded. Special thanks are due to Durkhani Aziz for her kindness and her relentless role as co-facilitator during the entire fieldwork, ensuring attendance of Community Development Council (CDC) members and Government officials in the focus group discussions and interviews. My sincere thanks to the CDC members for taking the time and effort to attend the discussions and to talk about their personal lives, and to the Governmental representatives for their helpful engagement with this research. October 2015 3 Women’s Participation in Community Decision-Making Spaces in Afghanistan Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................2 Acronyms............................................................................................................................4 Executive summary ........................................................................................................5 -

Afghanistan Rule of Law Project

AFGHANISTAN RULE OF LAW PROJECT FIELD STUDY OF INFORMAL AND CUSTOMARY JUSTICE IN AFGHANISTAN AND RECOMMENDATIONS ON IMPROVING ACCESS TO JUSTICE AND RELATIONS BETWEEN FORMAL COURTS AND INFORMAL BODIES Contracted under USAID Contract Number: DFD-I-00-04-00170-00 Task Order Number: DFD-1-800-00-04-00170-00 Afghanistan Rule of Law Project Checchi and Company Consulting, Inc. Afghanistan Rule of Law Project House #959, St. 6 Taimani iWatt Kabul, Afghanistan Corporate Office: 1899 L Street, NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA June 2005 This publication was prepared for the United States Agency for International Development. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND STUDY METHODOLOGY .............................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF INFORMAL AND CUSTOMARY JUSTICE.......................................4 A. Definition and Characteristics..........................................................................................................4 B. Recent Studies...................................................................................................................................6 C. Jirga and Shura..................................................................................................................................7 III. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS............................................................9 A. The Informal System ........................................................................................................................9 B. The Formal System.........................................................................................................................12 -

Between Hope and Fear: Rural Afghan Women Talk About Peace and War

Martine van Bijlert Between Hope and Fear: Rural Afghan women talk about peace and war Afghanistan Analysts Network, Special Report, July 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 3 AIMS AND STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT . 8 CHAPTER 1 METHODOLOGY . 12 CHAPTER 2 SECURITY IN THE DISTRICTS: FREEDOM FROM CONFLICT AND FEAR, FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT, ACCESS TO HEALTH AND EDUCATION . 16 2.1 Security in the districts: Do you consider your district to be safe? . 17 2.2 Freedom of movement: How often do you go outside your home? . 25 2.3 Impact of the war: Have you suffered any losses due to the war? . 32 CHAPTER 3 VIEWS ON THE US-TALEBAN AGREEMENT AND HOW IT MIGHT AFFECT THEIR LIFE . 36 3.1 The US-Taleban agreement: Have you heard of it? What are your feelings about it? . 37 3.2 Possible impact of a peace deal with the Taleban: How would it affect you personally? How would it affect what you could do? . 46 CHAPTER 4 IMAGINING WHAT PEACE COULD LOOK LIKE . 49 CHAPTER 5 LOOKING BACK AND LOOKING AHEAD: WHAT HAS BEEN GAINED, WHAT HAS BEEN LOST AND WHAT CAN ONLY BE HOPED FOR? . 59 5.1 Brief update, since we last spoke to the interviewees . 60 5.2 What these findings tell us . 63 ANNEXES . 68 ANNEX 1. INTERVIEW QUESTIONS FOR THE RURAL WOMEN AND PEACE STUDY . 69 ANNEX 2. OPEN LETTER TO WOMEN WORLD LEADERS BY “OUR VOICES OUR FUTURE” . 71 ANNEX 3. OPEN LETTER ADDRESSED TO THE TALEBAN BY “OUR VOICES OUR FUTURE” . 73 AUTHOR . 75 Rural Afghan women talk about peace and war 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the United States proceeds with the rapid and unconditional withdrawal of its troops from Afghanistan, an unrelenting Taleban offensive is pushing the Afghan government out of scores of districts across the country. -

Highlights Situation Overview

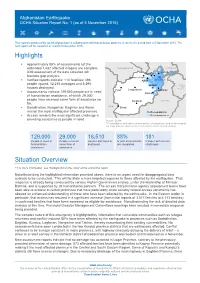

Afghanistan Earthquake OCHA Situation Report No. 1 (as of 5 November 2015) This report is produced by OCHA Afghanistan in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 4-5 November 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 8 November 2015. Highlights • Approximately 88% of assessments (of the estimated 1,482 affected villages) are complete. TURKMENISTAN TAJIKISTAN IOM assessment of the data collected will Fayzabad Kunduz facilitate gap analysis. Mazar-e-Sharif • Verified reports indicate: 110 fatalities; 498 Aybak Epicentre people injured; 12,215 damaged and 6,295 Kabul Jamm u and houses destroyed. Ka shmir • Herat Chaghcharan Jalalabad Assessments indicate 129,000 people are in need Gardez of humanitarian assistance, of which 29,000 people have received some form of assistance so Kandahar PAKISTAN far. IRAN • Badakhshan, Nangarhar, Baghlan and Kunar Zaranj remain the most earthquake affected provinces. Affected districts • Access remains the most significant challenge in Affected provinces providing assistance to people in need. Source: OCHA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. 129,000 29,000 18,510 88% 181 People in need of People received Houses damaged or of joint assessments Villages with access humanitarian some form of destroyed are completed. challenges assistance assistance Situation Overview + For more information, see “background on the crisis” at the end of the report. Notwithstanding the highlighted information provided above, there is an urgent need for disaggregated data analysis to be conducted. This will facilitate a more targeted response to those affected by the earthquake. -

Socio-Demographic and Economic Survey

Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Central Statistics Organization SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC SURVEY KABUL KABUL For more details, please contact: Central Statistics Organization Name: Mr. Eidmarjan Samoon P.O.Box: 1254, Ansari Watt Kabul,Afghanistan Phone: +930202104338 • E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cso.gov.af Design: Julie Pudlowski Consulting/Ali Mohaqqeq 2 Cover and inside photos: © UNFPA/CSO Afghanistan/2012 SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC SURVEY KABUL MESSAGE FROM CSO ,WLVZLWKJUHDWKRQRUDQGSOHDVXUHWRSUHVHQWWKLVÀQDOUHSRUWRQWKH6RFLR'HPRJUDSKLFDQG(FRQRPLF 6XUYH\ 6'(6 RI.DEXO3URYLQFH$IWHUJRLQJWKURXJKDOOWKRVHGLIÀFXOWLHVDQGFKDOOHQJHVWKDWVHHP WRQHYHUHQGFRQVLGHULQJWKHLPPHQVHVL]HRIWKHSURYLQFHWKXVPDNLQJWKHFRYHUDJHDUHDZLGHDQG UHTXLULQJPRUHPDQKRXUVDQGODERUWKDQRWKHUSUHYLRXVO\FRYHUHGSURYLQFHVLWMXVWÀOOVXVZLWKSULGH WRQRWHZHKDYHVXFFHVVIXOO\FRPSOHWHGWKHVXUYH\6XSHUYLVLRQRIFORVHWRVXUYH\ZRUNHUV KDVWUXO\EHHQGLIÀFXOWDVVRPHZRXOGTXLWLQWKHPLGGOHRIWKHRSHUDWLRQIRURWKHUMREVZKLFKLQDZD\ MHRSDUGL]HGVFKHGXOHVDQGWLPHOLQHVVRIÀHOGZRUNDVKLULQJQHZVXUYH\ZRUNHUVZRXOGDOVRUHTXLUH QHZWUDLQLQJV.DEXOKDVEHFRPHPRVWXUEDQL]HGDQGZKHUHPRVWHGXFDWHGZRUNHUVÀQGMREVLQWKH FLW\$QRWKHUGLIÀFXOW\LQWKHRSHUDWLRQLQ.DEXOLVWKHUHVSRQGHQWV·XQZLOOLQJQHVVWRFRRSHUDWHZKLFKLV FRPPRQZKHQXQGHUWDNLQJDVXUYH\LQDQXUEDQVHWWLQJDVXUEDQGZHOOHUVGRQRWHDVLO\WUXVWVWUDQJHUV 6RPHSDUWVRIWKHSURYLQFHZHUHDOVRFRQVLGHUHGLQVHFXUH %XWWKURXJKDOOWKRVHFKDOOHQJHVZHZHUHDEOHWRRYHUFRPHDQGVHHWKHIUXLWRIKDUGODERU:HQRZ KDYHLQIRUPDWLRQDERXW.DEXO3URYLQFHWKDWZLOOVHUYHDVEDVHVLQGHVLJQLQJTXDOLW\SURJUDPPHVIRUWKH FLWL]HQU\7KHVHGDWDVSHDNRIWKHWUXHHFRQRPLFDQGVRFLDOSLFWXUHRIWKHSURYLQFHWKDWPD\VHUYHDV -

Briefing Notes 14 September 2015

Group 22 - Information Centre Asylum and Migration Briefing Notes 14 September 2015 Afghanistan Security situation The situation remains unchanged. There were more attacks targeting government representatives and more fighting between insurgents and security forces. Fighting In the south-eastern province of Paktia at least six border police died in an attack by insurgents on 08 Sep- tember 15. Many insurgents and at least six members of the Afghan security forces were killed during a mili- tary operation in Paktika between 08 and 11 September 15 that also involved air strikes. The Taliban took control of parts of Raghestan district in the north-eastern province of Badakhshan on 11 September 15. Currently a fierce battle is raging over this district. At least four Afghan soldiers lost their lives when the Taliban took a military post in Baghlan (north-east) on 12 September 15. Five days of fighting in Khak-i-Safed district in the western province of Farah displaced hundreds of fami- lies. The Taliban stormed a prison in Ghazni (south-east) on 14 September 15 and liberated more than 430 pris- oners. There was further fighting and air strikes in the provinces of Kunar, (east), Ghazni, Khost (south-east), Kandahar, and Nimroz (south). Targeted attacks A police officer in Kabul died in the explosion of a bomb attached to his car on 08 September 15. The Tali- ban shot a district head in Uruzgan province (south) on 09 September 15. On the same day two Afghan sol- diers were blown up by a remotely detonated bomb in Kalakan district in Kabul province. -

13 Jan 2015 Kabul Highlights 0.Pdf

Kabul Province Socio-Demographic and Economic Survey Highlights Introduction Kabul was the fourth province to have successfully completed the Socio-Demographic and Economic Survey in the country. SDES in Kabul was launched in June 2013, jointly by the Central Statistics Organization (CSO) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) where the latter provided the technical assistance to the entire survey operations. SDES data serve as the benchmark for demographic information at the district level and to some extent, group of villages/enumeration areas. SDES is a continuing project designed to get those vital population information and at the same time to provide CSO staff additional experience in designing and conducting surveys in a large platform contributing much to one of the primary objectives of the institution’s capacity building. It is the only survey that addresses the need of local development planners for information at the lower level of disaggregation. There are other surveys that CSO has conducted but these are available only at the national and provincial levels. To achieve a responsive and appropriate policymaking, statistics plays a vital role. In Afghanistan, there has been a longstanding lack of reliable information at the provincial and district levels which hinders the policy making bodies and development planners to come up with comprehensive plans on how to improve the lives of Afghans. With SDES data, though it is not complete yet for the whole country, most of the important indicators in monitoring the progress towards the achievement of Afghanistan’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are being collected. I. Objectives, Methodology, Monitoring, Supervision, and Data Processing A. -

Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Opioid Drug Use Among the Youth in Kabul, Afghanistan

ORIGINAL RESEARCH: Socioeconomic factors associated with opioid drug use among the youth in Kabul, Afghanistan Abdul Shukoor Haidary1 1 Abstract Drugs are known to have dangerous consequences, but many people still use them. This study seeks to identify the factors influencing the use of opioid drugs by young adults in Kabul, Afghanistan. A descriptive as well as an analytical study was undertaken in six sites of Kabul. The study included 100 drug users (cases), and 120 non-drug users (control) for the quantitative part, and 24 local informants and 12 professional drug demand reduction informants as sources for the qualitative part. Qualitative data were analyzed using a thematic coded keyword approach whereby the data collected from key informants were grouped under emerging themes of the research objectives. Quantitative data were analyzed using chi- square statistical test as well as basic descriptive statistics. The study revealed that drugs are easily available around the city and villages of Kabul and are inexpensive. Opioid drugs were found to be popular among the larger Kabul population, and may be obtained from drug dealers and other drug users. The study found personal, behavioral, social and economic factors associated with opioids use including easy access to drugs, drug use among household members and friends, history of cigarette smoking and/or use of snuff, early age (15-22 years), illiteracy and low education, use of opium as painkiller for treatment, family problems and poor family relationships, peer pressure and influence, lack of sports and entertaining facilities, nearby poppy cultivation, war-related tension and problems, lack of proper drug prevention programs and lack of treatment facilities, unemployment and lack of job security, migration and displacements, frequent exposure to drugs, hard work at strenuous jobs and poor participation in community activities. -

Request for Proposal (RFP)

Request for Proposal (RFP) Opening Date: October 11, 2018 Closing Date: October 18, 2018 Duration: 4 Weeks Reference: UA/RFP/01 Dear Consultant / Firm: You are kindly requested to submit your Proposal for Baseline Survey of the Basic Healthcare for Returnees, IDPs and Host Communities in Walayati of Bagrami District and Bazari of Kalakan District, Kabul Province. In preparing your proposal, please refer to the attached hereto Annex 1: Terms of Reference for Project Baseline. Proposals may be submitted on or before Thursday, October 18, 2018 by email and/or mail courier to the address below: Union Aid Main Office House # 504, Shura Road, Karte 3, District 3, Kabul, Afghanistan Amjad Ahmad Safi Executive Director Email: [email protected], [email protected] Cell Phone: +93 786 717 111, +93 702 206 040 Please note that your Proposal must be prepared in English and valid for at least 30 days. The proposals should be submitted on due date as mentioned above. Late submission for any reason, will not be considered for evaluation. The applicants are requested if they are submitting the proposal by email, kindly ensure that the RFP should be signed/stamped/PDF format, and free from virus or corrupted files. The Technical Proposal and Financial Proposal shall be prepared separately. The RFPs received will be reviewed and evaluated based on completeness and compliance of the Proposal and responsiveness with the requirements of the Terms of Reference. Annex 1 Union Aid – Afghanistan Terms of Reference (TOR) – Project Baseline Implementing Organization -

National Area-Based Development Programme 2014

NATIONAL AREA-BASED DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2014 ANNUAL PROJECT PROGRESS REPORT UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME DONORS PROJECT INFORMATION Project ID: 00057359 (NIM) Duration: Phase III (July, 2009 – June, 2015) Strategic Plan Component: Promoting inclusive growth, gender equality and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) CPAP Component: Increased opportunities for income generation through promotion of diversified livelihoods, private sector development, and public private partnerships ANDS Component: Social and Economic Development Total Project Budget: USD $294,666,069 Annual Budget 2014: USD $53,384,064 Un-Funded Amount: USD $1,820,886 Implementing Partner: Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD) Responsible Agency: MRRD and UNDP Project Manager: Shoaib Khaksari – Acting PM Chief Technical Advisor: Vacant Responsible Assistant Country Director: Shoaib Timory COVER PAGE: Participants in a Women’s Economic Empowerment Project in the AliceGhan settlement for Internally Displaced Persons learning embroidery| Qarabagh district, Kabul province. Photo credit: NABDP © 2014 ACRONYMS ADDPs Annual District Development Plans AIRD Afghanistan Institute for Rural Development APRP Afghanistan Peace and Reintegration Programme ASGP Afghanistan Sub-National Governance Programme CDC Community Development Council CLDD Community Lead Development Department DCC District Coordination Councils DDA District Development Assembly DDP District Development Plan DIC District Information Center ERDA Energy for Rural Development -

DOWNLOAD PDF File

Quote of the Day Teamwork www.outlookafghanistan.net Teamwork” makes the dream” work, facebook.com/The.Daily.Outlook.Afghanistan but a vision becomes a nightmare Email: [email protected] when the leader has a big dream and a bad team. Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 Add: In front of Habibia High School, John C. Maxwell District 3, Kabul, Afghanistan Volume No. 4453 Saturday August 15, 2020 Asad 25, 1399 www.outlookafghanistan.net Price: 20/-Afs Coronavirus US Mulls Positivity Rate International Conference on Releasing Drug Drops to Afghanistan Kingpin KABUL - An international virtual confer- 15 Percent in ence on “Efforts of Uzbekistan and Paki- Demanded by stan in resolving the situation in Afghan- Afghanistan istan: Prospects for mutually beneficial Taliban KABUL - Coronavirus positivity rate cooperation” has been held. has declined to 15 percent in Afghani- The joint event of the Institute for Stra- stan, the country’s acting public health tegic and Regional Studies under the minister said on Thursday. President of the Republic of Uzbekistan Ahmad Javad Osmani said that recov- and the Pakistani Center for Global and ery cases have also increased to 71 per- Strategic Studies (CGSS) was attended cent in the country. by the heads and leading experts of an- He said that there were 9,000 active alytical and research centers of the two cases of coronavirus in Afghanistan. countries, as well as representatives of Referring to a grand assembly or Loya political-forming circles of Pakistan: dip- Jirga that was held in Kabul over the lomats, scientists and specialists in secu- weekend to decide the fate of 400 Tali- rity and foreign policy. -

Nato Unclassified // Fouo Rel Undss Nato Unclassified // Fouo Rel Undss

NATO UNCLASSIFIED // FOUO REL UNDSS IDC WEEKLY SECURITY NARATIVE: WEEK OF 04 – 10 OCT 2010 10 1013 All Offensive Incidents Throughout Afghanistan 04 – 10 OCT 2010 Offensive Incidents by RC from 04 - 10 OCT 10 RC- RC- S RC-SW E RC-C RC-W RC-N CJOA-A 4-Oct-10 45 54 32 0 0 5 136 5-Oct-10 36 58 25 1 6 2 128 6-Oct-10 33 57 23 0 9 1 123 7-Oct-10 36 61 33 0 3 1 134 8-Oct-10 31 50 19 0 7 4 111 9-Oct-10 37 45 32 1 3 1 119 10-Oct-10 34 62 33 0 8 5 142 WEEK TOTAL 252 387 197 2 36 19 893 Offensive Events by Date and RC 70 60 50 RC-S RC-SW 40 RC-E RC-C 30 RC-W Number of Number of Events 20 RC-N 10 0 0 010 010 010 2 2 /2 9 0/201 0/6/ 0/8/ 0/ 1 10/4/2010 10/5/2010 1 10/7/2010 1 1 0/ 1 Date RC – NORTH: 1. General Assessment of RC-N AOR The number of enemy initiated events in RC-N increased slightly (19 events this week versus 14 last week). However, that level has been within the average of the last several weeks (when the spike on 18 SEP during the Parliamentary Elections occurred). Most of the events this week were relatively insignificant direct fire incidents, but there NATO UNCLASSIFIED // FOUO REL UNDSS 1 NATO UNCLASSIFIED // FOUO REL UNDSS IDC WEEKLY SECURITY NARATIVE: WEEK OF 04 – 10 OCT 2010 10 1013 was one suicide bombing against German troops on 07 SEP 10 in northern Baghlan Province (circled on the map).