Zhang2019.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the Youtuber Zoella

In The Time of the Microcelebrity Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella Jerslev, Anne Published in: International Journal of Communication Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY-ND Citation for published version (APA): Jerslev, A. (2016). In The Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella. International Journal of Communication, 10, 5233-5251. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5078/1822 Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 5233–5251 1932–8036/20160005 In the Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella ANNE JERSLEV University of Copenhagen, Denmark This article discusses the temporal changes in celebrity culture occasioned by the dissemination of digital media, social network sites, and video-sharing platforms, arguing that, in contemporary celebrity culture, different temporalities are connected to the performance of celebrity in different media: a temporality of plenty, of permanent updating related to digital media celebrity; and a temporality of scarcity distinctive of large-scale international film and television celebrities. The article takes issue with the term celebrification and suggests that celebrification on social media platforms works along a temporality of permanent updating, of immediacy and authenticity. Taking UK YouTube vlogger and microcelebrity Zoella as the analytical case, the article points out that microcelebrity strategies are especially connected with the display of accessibility, presence, and intimacy online; moreover, the broadening of processes of celebrification beyond YouTube may put pressure on microcelebrities’ claim to authenticity. Keywords: celebrification, microcelebrity, YouTubers, vlogging, social media, celebrity culture YouTubers are a huge phenomenon online. -

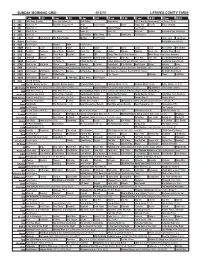

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

DISCOVER: Publicly Engaged Research at Lincoln

DISCOVER: Publicly engaged research at Lincoln Issue 1 Contents Introduction 3 Discover – exploring research at Lincoln 3 Public Engagement with Research – central to the mission of the University of Lincoln 3 PEARL 4 PEARL: Public Engagement for All with Research at Lincoln 4 PEARLs of Wisdom: PEARL Conference and Vice Chancellor’s Awards for Public Engagement with Research 2018 5 PEARL 2018 - 2019 Activity Grants 6 Viewpoint 8 PRaVDA - A positive beam of hope 8 News 10 University joins network supporting the involvement of patients and publics in health research 10 Together network: the transformation of a fully inclusive participation service 10 Research Higher: a new initiative developing research skills in FE students 11 The Community Lab 12 Communication across cultures: an international student-led conference 13 How Lincoln became the capital of earth architecture 13 Centres In Spotlight 14 Eleanor Glanville Centre – making university culture more inclusive 14 Breakfast Briefings’ by Lincoln Institute for Agri-food Technology (LIAT) share new ideas 15 Regular Events In Spotlight 16 A View of University of Lincoln LiGHTS Expo from Stephen Lonsdale 16 LiGHTS Spotlight: Bother with bacteria 17 LiGHTS Spotlight: DNA - The building blocks of food 18 Summer Scientist 19 Lincoln Philosophy Salon 20 Digital Student Ambassador Group – engaging people in the development and implementation of digital technologies 21 LIBS Connect: Embracing Diversity in the Workplace 22 Future 2.0 23 Publicly Engaged Research Projects 24 International Bomber -

Identity / Vlog

Identity Our deeply interconnected social media environment world challenges our understanding of how we fit into the world and demands that we craft and project a personal brand online. We create media, or watch and share it, in order to express and perform our identities and affiliate ourselves with our communities. Affiliative Loop Theater Affiliative videos target micro-audiences by reflecting Working within the constraints of the now-defunct social viewers back to themselves, operating on a level of intimacy video platform Vine, users iterated on a unique kind of and recognition similar to in-jokes. These videos rely on performance that relied on the 6.5-second loop as a defining recognizable phrases and situations, incentivizing viewers to formal element. Fast edits, absurd switches in logic, over-the- share them to their networks to express their own identities. top acting, and nonsensical phrases and situations coined a That affiliative videos cost little to produce allows them to number of memes and found the videos shared far outside target narrowly carved audiences that have not received such their originating platform as Vine compilations. The strange, specialized attention in traditional media. wacky humor was performed for friends and followers on the social network, an expression of self-identity. Shit Girls Say | 1:18 | 2011 | Shit THINGS ONLY TRANS GUYS Girls Say UNDERSTAND | 9:01 | 2016 | Sam Swipe up to scroll through a selection of Vine videos. Shit White Girls Say...to Black Girls | Barnes 2:01 | 2012 | chescaleigh -

An Analysis of Social Media Marketing in the Classical Music Industry

#CLASSICAL: AN ANALYSIS OF SOCIAL MEDIA MARKETING IN THE CLASSICAL MUSIC INDUSTRY Ms Annabelle Angela Lan Lee Royal Holloway, University of London (2017) A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Page 1 of 299 Page intentionally left blank. Page 2 of 299 Declaration of Authorship I Annabelle Angela Lan Lee hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 28 April 2017 Page 3 of 299 Page intentionally left blank. Page 4 of 299 Abstract With the re-emergence of social media in the 2000s and the increased worldwide usage of mobile devices, the impact of social media still cannot be ignored. From corporate businesses to popular culture, social media are now used in many sectors of society. Not least among these is the classical music industry. Artists and organisations have keenly capitalised on social media in the face of increasing budgetary reductions in the arts and long-held elitist perceptions of classical music. In addition, the classical music business has used social media to profit from economic growth, audiences, and public profiles, and to market accessibility, relevance, and value to a wider audience, notably, younger demographics and non-attenders. As a result, the classical music scene tries to engender technological determinism and digital optimism, ideologies reflecting discourses around Web 2.0/social media. Simultaneously, a so-called ‘digital divide’ is at risk. Various factors, for example, socioeconomic strata, greatly influence how classical music is marketed and branded on social media networks, however, they are barriers to access and enjoyment of the art, online and offline. -

Over 3 Million Youtube Creators Globally Receive Some Level Of

MEDIA FOLLOW THIS Social media entertainment – the kind that has seen huge growth on YouTube and other platforms – needs understanding if there is to be any measured policy response, writes STUART CUNNINGHAM from an Australian perspective ver the past 10 years or so, in the midst of all 1+ million; 2,000+ Australian YouTube channels the cacophony of change we are well familiar earned between $1,000 and $100,000 and more than with, a new creative industry was born. With 100 channels earned more than $100,000. More O my collaborator David Craig, a veteran than 550,000 hours of video were uploaded by Hollywood executive now teaching at the University Australian creators and over 90% of the followers of of Southern California Annenberg School for Australian channels were international. Communication and Journalism, I have been That’s only YouTube, and only the programmatic examining the birth and early childhood of what advertising revenue that can be tracked by Google. we call social media entertainment. It is peopled by A Google-funded study by AlphaBeta2 estimates that cultural leaders, entertainers and activists most of the number of content creators in Australia has whom you may be very unfamiliar with... Here more than doubled over the past 15 years, almost are some of them – Hank Green, Casey Neistat, wholly driven by the entry of 230,000 new creators PewDiePie, Tyler Oakley. of online video content. The same study estimates We understand social media entertainment to be that online video has created a A$6 billion an emerging industry based on previously amateur consumer surplus (the benefit that consumers get creators professionalising and monetising their in excess of what they have paid for that service). -

Youtube Marketing: Legality of Sponsorship and Endorsement in Advertising Katrina Wu, University of San Diego

From the SelectedWorks of Katrina Wu Spring 2016 YouTube Marketing: Legality of Sponsorship and Endorsement in Advertising Katrina Wu, University of San Diego Available at: http://works.bepress.com/katrina_wu/2/ YOUTUBE MARKETING: LEGALITY OF SPONSORSHIP AND ENDORSEMENTS IN ADVERTISING Katrina Wua1 Abstract YouTube endorsement marketing, sometimes referred to as native advertising, is a form of marketing where advertisements are seamlessly incorporated into the video content unlike traditional commercials. This paper categorizes YouTube endorsement marketing into three forms: (1) direct sponsorship where the content creator partners with the sponsor to create videos, (2) affiliated links where the content creator gets a commission resulting from purchases attributable to the content creator, and (3) free product sampling where products are sent to content creators for free to be featured in a video. Examples in each of the three forms of YouTube marketing can be observed across virtually all genres of video, such as beauty/fashion, gaming, culinary, and comedy. There are four major stakeholder interests at play—the YouTube content creators, viewers, YouTube, and the companies—and a close examination upon the interplay of these interests supports this paper’s argument that YouTube marketing is trending and effective but urgently needs transparency. The effectiveness of YouTube marketing is demonstrated through a hypothetical example in the paper involving a cosmetics company providing free product sampling for a YouTube content creator. Calculations in the hypothetical example show impressive return on investment for such marketing maneuver. Companies and YouTube content creators are subject to disclosure requirements under Federal law if the content is an endorsement as defined by the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”). -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

'I' of the Front Camera

The ‘I’ of the Front Camera 1 Navajyoti, International Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Research Volume 3, Issue 2, February 2019 THE ‘I’ OF THE FRONT CAMERA: WHERE EVERYBODY IS AN AUTEUR Chandana Surapaneni Mount Carmel College Abstract: Identity construction in the post digital revolution era has taken a futuristic narrative, where the role of technology in capturing the nuances of daily life has been downplayed by factors such as legitimacy and accountability. One such gradation is the emergence of the idea of Instant sharing through vlog channels. To avoid ambiguities of terms, a vlog is typically an audio visual clip that brings the viewer closer to a certain experience of lifestyle, traveling, clothing, eating, or even daily life that is highly specific to the vlogger’s point of view. This paper aims to highlight the problems in theorising the concept of vlogging as a media object. The author of this paper attempts to highlight the dynamism involved in the field of vlogging and offers a critique of its demystifying nature. The idea of a vlog as a self theorising media object and its role in the conception of the “I” is traced through the understanding of vlogging as a mundanely extraordinary experience with a wide network of sinthomatic expressions that define what is personal and private. This paper questions the applicability of the postmodern notion of “we are all auteurs” and the possibility of experiencing vlogging as a scope providing medium and not as a self-theorising entity. Keywords: Identity, Legitimacy, Digital, Vlogs, Media object, Demystifying, Self Theorising, Mundanely Extraordinary, Personal and Private, Auteurs, Scope Medium. -

An Analysis on Youtube Rewinds

KADİR HAS UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES NEW MEDIA DISCIPLINE AREA POPULAR CULTURE REPRESENTATION ON YOUTUBE: AN ANALYSIS ON YOUTUBE REWINDS SİDA DİLARA DENCİ SUPERVISOR: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Çiğdem BOZDAĞ MASTER’S THESIS ISTANBUL, AUGUST, 2017 i POPULAR CULTURE REPRESENTATION ON YOUTUBE: AN ANALYSIS ON YOUTUBE REWINDS SİDA DİLARA DENCİ SUPERVISOR: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Çiğdem BOZDAĞ MASTER’S THESIS Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Kadir Has University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s in the Discipline Area of New Media under the Program of New Media. ISTANBUL, AUGUST, 2017 i ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgements List of Figures List of Chapters 1. Introduction 2. Literature Review 2.1 Commercializing Culprit or Social Cement? What is Popular Culture? 2.2 Sharing is caring: user-generated content 2.3 Video sharing hype: YouTube 3. Research Design 3.1 Research Question 3.2 Research Methodology 4. Research Findings and Analysis 4.1 Technical Details 4.1.1 General Information about the Data 4.1.2 Content Analysis on Youtube Rewind Videos 5. Conclusion References iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first and foremost like to thank my thesis advisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Çiğdem BOZDAĞ of the Faculty of Communication at Kadir Has University. Prof. Bozdağ always believed in me even I wasn’t sure of my capabilities. She kindly guided me through the tunnel of the complexity of writing a thesis. Her guidance gave me strength to keep myself in right the direction. I would like to thank Assoc. Prof. Dr. Eylem YANARDAĞOĞLU whose guidance was also priceless to my studies. -

Mainstream Media Representations of Youtube Celebrities DELLER, Ruth A

‘Zoella hasn’t really written a book, she’s written a cheque’: Mainstream media representations of YouTube celebrities DELLER, Ruth A. <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4935-980X> and MURPHY, Kathryn <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1146-7100> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/23569/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version DELLER, Ruth A. and MURPHY, Kathryn (2019). ‘Zoella hasn’t really written a book, she’s written a cheque’: Mainstream media representations of YouTube celebrities. European journal of cultural studies. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk ‘Zoella hasn’t really written a book, she’s written a cheque’: Mainstream media representations of YouTube celebrities. Abstract In this paper, we present a thematic analysis of broadcast and print media representations of YouTube celebrity. Youth-oriented media have capitalised on the phenomenon, placing vloggers alongside actors and pop stars. However, in much adult-oriented mainstream media, YouTubers are presented as fraudulent, inauthentic, opportunist and talentless, making money from doing nothing. Key themes recur in coverage, including YouTubers’ presumed lack of talent and expertise, the alleged dangers they present and the argument that they are not ‘really famous’. YouTubers’ claims to fame are thus simultaneously legitimised by giving them coverage and delegitimised within said coverage, echoing media treatment of other ‘amateur’ celebrities such as reality stars and citizen journalists. -

Journal of International Media & Entertainment

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL MEDIA & ENTERTAINMENT LAW PUBLISHED BY THE DONALD E. BIEDERMAN ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA LAW INSTITUTE OF SOUTHWESTERN LAW SCHOOL IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION FORUMS ON COMMUNICATIONS LAW AND THE ENTERTAINMENT AND SPORTS INDUSTRIES Volume 9, Number 1 2020-2021 SYMPOSIUM FAKE NEWS AND “WEAPONIZED DEFAMATION”: GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES EDITOR’S NOTE ARTICLES RICO As a Case-Study in Weaponizing Defamation and the International Response to Corporate Censorship Charlie Holt & Daniel Simons The Defamation of Foreign State Leaders in Times of Globalized Media and Growing Nationalism Alexander Heinze Defamation Law in Russia in the Context of the Council of Europe (COE) Standards on Modern Freedom Elena Sherstoboeva Rethinking Non-Pecuniary Remedies for Defamation: The Case for Court-Ordered Apologies Wannes Vandenbussche JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL MEDIA & ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 9, NO. 1 ■ 2020–2021 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL MEDIA & ENTERTAINMENT LAW Volume 9 Number 1 2020–2021 PUBLISHED BY THE DONALD E. BIEDERMAN ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA LAW INSTITUTE OF SOUTHWESTERN LAW SCHOOL IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION FORUMS ON COMMUNICATIONS LAW AND THE ENTERTAINMENT AND SPORTS INDUSTRIES Mission Statement: The Journal of International Media & Entertainment Law is a semi- annual publication of the Donald E. Biederman Entertainment and Media Law Institute of Southwestern Law School in association with the American Bar Association Forums on Communications Law and the Entertainment and Sports Industries. The Journal provides a forum for exploring the complex and unsettled legal principles that apply to the production and distribution of media and entertainment in an international, comparative, and local context. The legal issues surrounding the creation and dissemination of news and entertainment products on a worldwide basis necessarily implicate the laws, customs, and practices of multiple jurisdictions.