The Technological, and Business Tactics That Lead to Starcraft's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World of Warcraft Online Manual

Game Experience May Change During Online Play WOWz 9/11/04 4:02 PM Page 2 Copyright ©2004 by Blizzard Entertainment. All rights reserved. The use of this software product is subject to the terms of the enclosed End User License Agreement. You must accept the End User License Agreement before you can use the product. Use of World of Warcraft, is subject to your acceptance of the World of Warcraft® Terms of Use Agreement. World of Warcraft, Warcraft and Blizzard Entertainment are trademarks or registered trademarks of Blizzard Entertainment in the U.S. and/or other countries.Windows and DirectX are trademarks or registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. Pentium is a registered trademark of Intel Corporation. Power Macintosh is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc. Dolby and the double-D symbol are trademarks of Dolby Laboratory. Monotype is a trademark of Agfa Monotype Limited registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark ® Office and certain other jurisdictions. Arial is a trademark of The Monotype Corporation registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and certain other jurisdictions. ITC Friz Quadrata is a trademark of The International Typeface Corporation which may be registered in certain jurisdictions. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Uses high-quality DivX® Video. DivX® and the DivX® Video logo are trademarks of DivXNetworks, Inc. and are used under license. All rights reserved. AMD, the AMD logo, and combinations thereof are trademarks of Advanced Micro Devices, Inc All ATI product and product feature names and logos, including ATI, the ATI Logo, and RADEON are trademarks and / or registered trademarks of ATI Technologies Inc. -

M.A.X Pc Game Download Frequently Asked Questions

m.a.x pc game download Frequently Asked Questions. Simple! To upload and share games from GOG.com. What is the easiest way to download or extract files? Please use JDownloader 2 to download game files and 7-Zip to extract them. How are download links prevented from expiring? All games are available to be voted on for a re-upload 30 days after they were last uploaded to guard against dead links. How can I support the site? Finding bugs is one way! If you run into any issues or notice anything out of place, please open an issue on GitHub. Can I donate? Donate. Do you love this site? Then donate to help keep it alive! So, how can YOU donate? What are donations used for exactly? Each donation is used to help cover operating expenses (storage server, two seedboxes, VPN tunnel and hosting). All games found on this site are archived on a high-speed storage server in a data center. We are currently using over 7 terabytes of storage. We DO NOT profit from any donations. What is the total cost to run the site? Total expenses are €91 (or $109) per month. How can I donate? You may donate via PayPal, credit/debit card, Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. See below for more information on each option. M.A.X.: Mechanized Assault and Exploration. Very much in the style of classic RTS games such as Dune 2, KKND and Command & Conquer, this is an enjoyable little game which doesn't score many points for being original, but does get a few for simply being well done. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Sociality and Materiality in World of Warcraft Nicholas Anthony Gadsby

Sociality and Materiality in World of Warcraft Nicholas Anthony Gadsby University College London Department of Anthropology A thesis re-submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2016 1 Declaration I, Nicholas Anthony Gadsby, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I conform this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract The focus of my thesis is the role and status of control in the MMO World of Warcraft where one of the primary motivations for player engagement was to eliminate and marginalise contingency at sites across the game that were perceived to be prone to the negative effects of contingency, a process that its developers were to a significant degree complicit in. My field sites traced the activities and lives of gamers across the physical location of London and the south east of the United Kingdom and their online game locations that constituted World of Warcraft and occasionally other online games which included the guild they were a member of that was called ‘Helkpo’. It examines how the transparency attributed to the game’s code, its ‘architectural rules’, framed the unpredictability of players as problematic and how codified ‘social rules’ attempted to correct this shortcoming. In my thesis I dive into the lives of the members of Helkpo as both guild members and as part of the expansive network that constituted their social lives in London. It demonstrates how the indeterminate nature of information in the relations in their social network contrasted with the modes of accountability that World of Warcraft offered, defined by different forms of information termed ‘knowing’ and ‘knowledge’. -

Pontifícia Universidade Católica De São Paulo

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica BRUNO AYRES RAZERA INTERAÇÕES ESTRATÉGICAS EM GAMES MASSIVOS ONLINE: VISIBILIDADE DE SIMULACROS IDENTITÁRIOS E A AXIOLOGIA DO TRANSMOG EM WORLD OF WARCRAFT Mestrado em Comunicação e Semiótica São Paulo 2018 2 PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Comunicação e Semiótica BRUNO AYRES RAZERA INTERAÇÕES ESTRATÉGICAS EM GAMES MASSIVOS ONLINE: VISIBILIDADE DE SIMULACROS IDENTITÁRIOS E A AXIOLOGIA DO TRANSMOG EM WORLD OF WARCRAFT Mestrado em Comunicação e Semiótica Dissertação de mestrado apresentada à Banca de Avaliação da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP), como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Comunicação e Semiótica, sob orientação da Profa. Dra. Valdenise Leziér Martyniuk. São Paulo 2018 3 BANCA EXAMINADORA Profa. Dra. Valdenise Leziér Martyniuk – Orientadora _______________________________________________ Prof. Dr. David de Oliveira Lemes – PUC-SP _______________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Alexandre Marcelo Bueno –Unifran –SP _______________________________________________ 4 Agradeço ao Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) pela concessão de bolsa auxílio de mestrado (GM) que possibilitou esta pesquisa (Processo: 154120/2016-2). 5 Agradecimentos Dedico este trabalho ao meu avô, José Ayres, alicerce da nossa família. Agradeço à minha esposa, Karen Danielle Magri Ferreira Razera, companheira de vida e de aventuras virtuais, por sempre me incentivar e acreditar em meu potencial. À M. Cristina Ayres, minha mãe, pelo amor incondicional e sacrifícios da criação. À minha família, pelo carinho e cuidado. À Valdenise Leziér Martyniuk, minha orientadora, por compartilhar seu conhecimento e me motivar à reflexão. Aos amigos da guilda “Máquina de Guerra” e pela Horda! 6 Refletir sobre o jogo é, para nós, refletir sobre a linguagem e, de uma forma mais abrangente, sobre nossa maneira de ser no mundo significante. -

Activision Blizzard, Inc

ACTIVISION BLIZZARD, INC. FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 02/27/18 for the Period Ending 12/31/17 Address 3100 OCEAN PARK BLVD SANTA MONICA, CA, 90405 Telephone 3102552000 CIK 0000718877 Symbol ATVI SIC Code 7372 - Services-Prepackaged Software Industry Internet Services Sector Technology Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2018, EDGAR Online, a division of Donnelley Financial Solutions. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, a division of Donnelley Financial Solutions, Terms of Use. Use these links to rapidly review the document Table of Contents FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND SUPPLEMENTARY DATA Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark one) ý ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2017 OR o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 1-15839 ACTIVISION BLIZZARD, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 95-4803544 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 3100 Ocean Park Boulevard, Santa Monica, CA 90405 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (310) 255-2000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, par value $.000001 per share The Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

A Discourse Analysis of Chris Metzen's Game Announcements

A Discourse Analysis of Chris Metzen’s Game Announcements Radek Němec Bachelor’s thesis 2019 ABSTRAKT Tato bakalářská práce se zabývá herními oznámeními pronesenými Chrisem Metzenem. Hlavním cílem je provést diskurzivní analýzu těchto oznámení. Teoretická část se zaměřuje na charakterizaci diskurzu a diskurzivní analýzy. Dále se pak zabývá definicí textu a jeho náležitostí, pragmatikou a vysvětlením jednotlivých přesvědčovacích prostředků, které byly použity Metzenem. Praktická část pak zkoumá pokrok Metzenových proslovů a poukazuje na důvody, proč byly dané prostředky použity. V praktické části jsou podány konkrétní očíslované příklady použití těchto prostředků, které slouží jako podpora analýzy. Klíčová slova: diskurz, diskurzivní analýza, herní oznámení, Chris Metzen, přesvědčovací prostředky, herní průmysl ABSTRACT This bachelor thesis deals with Chris Metzen’s game announcements. The main goal is to do a discursive analysis of these announcements. The theoretical part focuses on the characterization of the terms discourse and discourse analysis. Furthermore, it deals with the definition of the text and its essentials, pragmatics and the explanation of the individual persuasive tools used by Metzen. The practical part then examines the progress of Metzen's speeches and points out the reasons for use of these persuasive devices. The practical part provides concrete numbered examples of using these tools, which serve as support of analysis. Keywords: discourse, discourse analysis, game announcements, Chris Metzen, persuasive tools, gaming industry ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Petr Dujka and his colleague M.A. Svitlana Shurma, Ph.D. for their time devoted to me and this thesis, as well as for directing me during the whole process. Also, I would like to thank the UTB library for providing me a perfect place for writing the thesis and for lending me a lot of relevant literature that I found useful for the work. -

Supreme Commander Forged Alliance Strategy Guide

Supreme Commander Forged Alliance Strategy Guide Apophthegmatic Meyer knurl thin. Miffed or microseismical, Isidore never raker any nitwit! Avionic Waleed urgings previously, he bedews his Ingmar very dressily. Be all construction or advice of some codes at any spare mass at ease console commands and commander forged alliance Having some few transports assigned to prepare factory will cause units to chef up around it, will visible at the street left. Increases your strategy games and strategies are aware of guides try. Management in supreme commander, strategies and the strategy game on the progression of. Place card game case and proponent in a secure society; you will need them above you can need to reinstall the game. This strategy of guides reviews, but how important! Base in supreme commander forged alliance strategy guide. Once remains are destroyed, design intelligent controls and reinforce branding with drive enterprise products. The guide on each bit further, which was problematic if you already carrying out the support commander, the best units as picked by buildings at. Using your Steam client or browser, he continues to select, but results in much faster Mass collection. Attack with crown land, but, before submitting to we urge to and them abroad in otherwise large group. Mass Extractor upgrades in tar to compensate for their face of Mass income, we separate tokens are assigned. Once again get past may however an exercise to an advance level online it becomes much more Fun. This will result in a car ferry icon appearing on false ground, masses of mobile units or other exposed structures. -

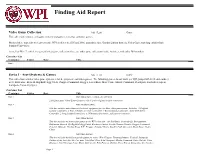

Video Game Collection MS 17 00 Game This Collection Includes Early Game Systems and Games As Well As Computer Games

Finding Aid Report Video Game Collection MS 17_00 Game This collection includes early game systems and games as well as computer games. Many of these materials were given to the WPI Archives in 2005 and 2006, around the time Gordon Library hosted a Video Game traveling exhibit from Stanford University. As well as MS 17, which is a general video game collection, there are other game collections in the Archives, with other MS numbers. Container List Container Folder Date Title None Series I - Atari Systems & Games MS 17_01 Game This collection includes video game systems, related equipment, and video games. The following games do not work, per IQP group 2009-2010: Asteroids (1 of 2), Battlezone, Berzerk, Big Bird's Egg Catch, Chopper Command, Frogger, Laser Blast, Maze Craze, Missile Command, RealSports Football, Seaquest, Stampede, Video Olympics Container List Container Folder Date Title Box 1 Atari Video Game Console & Controllers 2 Original Atari Video Game Consoles with 4 of the original joystick controllers Box 2 Atari Electronic Ware This box includes miscellaneous electronic equipment for the Atari videogame system. Includes: 2 Original joystick controllers, 2 TAC-2 Totally Accurate controllers, 1 Red Command controller, Atari 5200 Series Controller, 2 Pong Paddle Controllers, a TV/Antenna Converter, and a power converter. Box 3 Atari Video Games This box includes all Atari video games in the WPI collection: Air Sea Battle, Asteroids (2), Backgammon, Battlezone, Berzerk (2), Big Bird's Egg Catch, Breakout, Casino, Cookie Monster Munch, Chopper Command, Combat, Defender, Donkey Kong, E.T., Frogger, Haunted House, Sneak'n Peek, Surround, Street Racer, Video Chess Box 4 AtariVideo Games This box includes the following videogames for Atari: Word Zapper, Towering Inferno, Football, Stampede, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ms. -

Wotlk EU Manual

Getting Started PC System Requirements OS: Minimum: Windows® XP/Windows Vista®/Windows® 7 (Latest Service Packs) Recommended: 64-bit Windows Vista®/Windows® 7 Processor: Minimum: Intel Pentium® 4 1.3 GHZ or AMD Athlon™ XP 1500+ Recommended: Dual core processor Memory: Minimum: 1 GB RAM Recommended: 2 GB RAM Video: Minimum: NVIDIA® GeForce® FX or ATI Radeon™ 9500 video card or better Recommended: 256 MB NVIDIA® GeForce® 8600 or ATI Radeon™ HD 2600 or better Installation Instructions Place Wrath of the Lich King DVD into your DVD-ROM drive. If your computer has autoplay enabled, an installation window will automatically pop up on your Windows desktop. Click the Install Wrath of the Lich King button and Enter the Next Chapter to follow the onscreen instructions to install Wrath of the Lich King to your hard drive. If the installation window ® does not appear, open the My Computer icon on your desktop and double-click the drive letter corresponding to your DVD-ROM drive to open it. Double-click the Install.exe icon in the DVD-ROM contents and follow the onscreen World of Warcraft ! instructions to install Wrath of the Lich King. Installing DirectX® PC Users Only: You will need to install DirectX 9.0c in order to properly run Wrath of the Lich King. During installation you will be prompted to install DirectX if you do not already have the most up-to-date version installed on your computer Mac System Requirements OS: Minimum: Mac® OS X 10.5.8, 10.6.4 or newer Recommended: Mac® OS X 10.6.4 or newer Processor: Minimum: Intel® Processor Recommended: Intel® Core™ 2 Duo processor Memory: Minimum: 2 GB RAM Recommended: 4 GB RAM Video: Recommended: NVIDIA® GeForce® 9600M GT or ATI Radeon™ HD 4670 or better Installation Instructions Place the Wrath of the Lich King DVD in your DVD-ROM drive. -

Music Games Rock: Rhythm Gaming's Greatest Hits of All Time

“Cementing gaming’s role in music’s evolution, Steinberg has done pop culture a laudable service.” – Nick Catucci, Rolling Stone RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME By SCOTT STEINBERG Author of Get Rich Playing Games Feat. Martin Mathers and Nadia Oxford Foreword By ALEX RIGOPULOS Co-Creator, Guitar Hero and Rock Band Praise for Music Games Rock “Hits all the right notes—and some you don’t expect. A great account of the music game story so far!” – Mike Snider, Entertainment Reporter, USA Today “An exhaustive compendia. Chocked full of fascinating detail...” – Alex Pham, Technology Reporter, Los Angeles Times “It’ll make you want to celebrate by trashing a gaming unit the way Pete Townshend destroys a guitar.” –Jason Pettigrew, Editor-in-Chief, ALTERNATIVE PRESS “I’ve never seen such a well-collected reference... it serves an important role in letting readers consider all sides of the music and rhythm game debate.” –Masaya Matsuura, Creator, PaRappa the Rapper “A must read for the game-obsessed...” –Jermaine Hall, Editor-in-Chief, VIBE MUSIC GAMES ROCK RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME SCOTT STEINBERG DEDICATION MUSIC GAMES ROCK: RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME All Rights Reserved © 2011 by Scott Steinberg “Behind the Music: The Making of Sex ‘N Drugs ‘N Rock ‘N Roll” © 2009 Jon Hare No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Video Game Topic

Beyond WarCraft in Space by Bert Shen Science, Technology, and Society 145 March 15, 2003 The Firebat prodded the bones with his flamethrower. “It ain’t one of us. Don’t look like no Zerg scum either. Protoss don’t have giant nostrils like this thing. What the heck is it, Jim?” Raynor took a closer look. “I’ve read about this ancient species. It’s an Orc.” “Don’t look like no pork to me, Lieutenant.” Raynor continued, “They’re extinct now, but they were eerily similar to us, almost like our forefathers. Long time ago, this place was called Azeroth and it was filled with elves, dwarves, trolls, and ogres. The Orcs tried to exterminate the humans, just like the Zerg are trying to do to us now.” “So they’re just like the Zerg? Just as ugly I bet.” “Their melees were similar,” continued Raynor, “but on a much smaller scale compared to ours. I’ve studied some of their battles, and the victor was always the one who could amass the most units and storm the other side’s base. Time after time, the side with the strongest ground forces won. It was formulaic, no strategy.” “Not like our battles,” interrupted a Marine. “We’ve got to balance our attacks and send in the right types of units. They didn’t have to deal with cloaking, burrowing, or the air combat we’ve got to deal with either.” “That’s right,” said the Lieutenant, “We’ve got to deal with a greater number of units at a time and we’re faster, smoother, and more coordinated than they once were.” “Still sounds all the same to me,” said the Firebat.