Research and Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FROM the MUSIC DEPARTMENT of the NIŠ NATIONAL THEATER to the NIŠ SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA (1953–1965) UDC 785.11”1953/1965” (497.11 Niš)

FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Visual Arts and Music Vol. 6, No 1, 2020, pp. 19 - 32 https://doi.org/10.22190/FUVAM2001019C Original scientific paper ORCHESTRAL PRACTICE IN NIŠ AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR – FROM THE MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF THE NIŠ NATIONAL THEATER TO THE NIŠ SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA (1953–1965) UDC 785.11”1953/1965” (497.11 Niš) Sonja Cvetković University of Niš, Faculty of Arts in Niš, Republic of Serbia Abstract. The paper deals with the founding of a professional orchestral practice in Niš, and its beginnings that are related to the 1950s and 1960s. The research, conducted with the aim of considering the cultural and artistic contribution of the symphony orchestra, as an institution, to the dynamics of the musical life in Niš is based on local press insights and available archival material. Frequent changes in the organizational structure, financial and personnel problems, artistic rises and falls, polemical tones of the cultural public that followed the establishing of the orchestral practice in Niš after the Second World War testify to the dynamic atmosphere during the first decade of existence and artistic work of symphony orchestras that were predecessors of the Niš Symphony Orchestra, which until the mid-1960s was the only symphony orchestra ensemble in Serbia besides the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra. Key words: Niš, concert orchestral practice, Music Department of the Niš National Theater, Niš Philharmonic Orchestra, City Symphony Orchestra INTRODUCTION Concert orchestral activity is a very important factor in the structure of the entire musical life of a community. Considering its continuity/discontinuity, professional engagement, and the institutional organization one can point not only to musical but also to many other aspects – ideological, cultural, economic – that have marked a certain historical period. -

Bruno Brun – Rodonačelnik Beogradske Škole Klarineta

Miloš Brun UDK: 78.071.1:929 Brun B. OŠ „Radojka Lakić“ Prilog biografiji Beograd, Srbija [email protected] Bruno Brun – rodonačelnik beogradske škole klarineta Sažetak Profesor Bruno Brun rodonačelnik je tzv. beogradske škole klarineta, čiji su izdanci najpoznatiji izvođači i nastavnici sa prostora bivših jugoslovenskih republika. Iako iz siromašne rudarske porodice, ovaj rođeni pedagog uspeo je da uz svakodnevno stručno usavršavanje, posvećenost voljenom instrumentu i predanost svojim učenicima dosegne nivo najvišeg društvenog uvažavanja. Kao član mnogobrojnih orkestara pre, tokom i nakon Drugog svetskog rata, ali i kao solista i član manjih muzičkih sastava, svoju umešnost na klarinetu iskazivao je i na koncertnim nastupima širom sveta. Svoj talenat iskazao je i kroz komponovanje, zatim sastavljajući udžbenike za polaznike škola klarineta, ali se naročito istakao i kao borac za bolje uslove života i rada kulturnih radnika Srbije, te je otuda i nagrađen Sedmojulskom nagradom. Ključne reči: Bruno Brun, klarinetista, profesor, kompozitor Bruno Brun je rođen 14. avgusta 1910. godine u Hrastniku (Slo- venija), u porodici kolonista koja je, kao i većina u tom rudarskom mestu, doseljena u prvoj polovini 19. veka iz Tirola. Kao jedno od devetoro dece rudara Hermana i domaćice Eme, Bruno je pod uti- cajem sestre Marije veoma rano zavoleo violinu, a na savet starijeg brata Jožeta, inače fagotiste, krenuo je „trbuhom za kruhom“, ali i za svojim snovima, u daleki Vršac. Još kao nebrijani pubertetlija (tj. sa 13 godina) upisao se u Vojnu muzičku školu i započeo školovanje i na klarinetu. Ubrzo će odlučiti da upravo taj duvački instrument bude njegovo životno opredeljenje (Šotra 1967, 4). Nakon trogodi- šnjeg školovanja, budući da je bio jedan od darovitijih đaka, dobio je 231 SLOVENIKA IV 2018 priliku da radi kao pomoćnik nastavnika klarineta1 i na taj je način stekao i svoja prva iskustva iz oblasti muzičke pedagogije. -

Bitstream 33844.Pdf (1.560Mb)

Časopis za kulturu, nauku i obrazovanje Časopis za kulturo, znanost in izobraževanje Beograd 2018. Časopis za kulturu, nauku i obrazovanje / Časopis za kulturo, znanost in izobraževanje IV (2018) ISSN: 2466-555X ISSN: 2466-2852 (Online) Izdavač / Založnik Univerzitet u Beogradu, Filološki fakultet / Univerza v Beogradu, Filološka fakulteta i/in Nacionalni savet slovenačke nacionalne manjine u Republici Srbiji / Nacionalni svet slovenske narodne manjšine v Republiki Srbiji Za izdavača / Za založbo Prof. dr Ljiljana Marković Saša Verbič Adresa izdavača / Naslov uredništva Terazije 3/IX, 11000 Beograd tel +381 (0)11 33 40 845 e-mail: [email protected] www.slovenci.rs Lektura i korektura / Lektoriranje in korektura Sofija Miloradović (srpski), Milica Ševkušić (engleski), Tanja Tomazin (slovenački) Dizajn korica i teksture / Oblikovanje naslovnice in teksture Marija Vauda Grafičko oblikovanje / Grafično oblikovanje Jasmina Pucarević Tiraž / Naklada 300 Štampa / Tisk SGC Beograd Štampanje publikacije finansirano je iz sredstava Ministarstva kulture i informisanja Republike Srbije i Nacionalnog saveta slovenačke nacionalne manjine u Republici Srbiji / Tiskanje publikacije je financirano iz sredstev Ministrstva kulture in informiranja Republike Srbije in Nacionalnega sveta slovenske narodne manjšine v Republiki Srbiji. Glavni i odgovorni urednici / Glavni in odgovorni urednici Prof. dr Maja Đukanović (Univerzitet u Beogradu, Filološki fakultet, Srbija) i/in Biljana Milenković-Vuković (Etnografski institut SANU, Beograd, Srbija) Međunarodna redakcija / Mednarodni uredniški odbor Dr. Tatjana Balažic Bulc (Univerza v Ljubljani, Filozofska fakulteta, Slovenija), M.A. Dejan Georgiev (Univerza v Ljubljani, Filozofska fakulteta, Slovenija), dr. Cvetka Hedžet Tóth (Univerza v Ljubljani, Filozofskaf akulteta, Slovenija), prof. dr Borko Kovačević (Univerzitet u Beogradu, Filološki fakultet, Srbija), Silvija Krejaković (Muzej grada Beograda – Zavičajni muzej Zemun, Srbija), prof. -

Instructions for Authors

Journal of Science and Arts Supplement at No. 2(13), pp. 157-161, 2010 THE CLARINET IN THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF THE 20TH CENTURY FELIX CONSTANTIN GOLDBACH Valahia University of Targoviste, Faculty of Science and Arts, Arts Department, 130024, Targoviste, Romania Abstract. The beginning of the 20th century lay under the sign of the economic crises, caused by the great World Wars. Along with them came state reorganizations and political divisions. The most cruel realism, of the unimaginable disasters, culminating with the nuclear bombs, replaced, to a significant extent, the European romanticism and affected the cultural environment, modifying viewpoints, ideals, spiritual and philosophical values, artistic domains. The art of the sounds developed, being supported as well by the multiple possibilities of recording and world distribution, generated by the inventions of this epoch, an excessively technical one, the most important ones being the cinema, the radio, the television and the recordings – electronic or on tape – of the creations and interpretations. Keywords: chamber music of the 20th century, musical styles, cultural tradition. 1. INTRODUCTION Despite all the vicissitudes, music continued to ennoble the human souls. The study of the instruments’ construction features, of the concert halls, the investigation of the sound and the quality of the recordings supported the formation of a series of high-quality performers and the attainment of high performance levels. The international contests organized on instruments led to a selection of the values of the interpretative art. So, the exceptional professional players are no longer rarities. 2. DISCUSSIONS The economic development of the United States of America after the two World Wars, the cultural continuity in countries with tradition, such as England and France, the fast restoration of the West European states, including Germany, represented conditions that allowed the flourishing of musical education. -

Mariam Adam & Berginald Rash

Vol. 47 • No. 4 September 2020 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Research Competition Winner: Humming and Singing While Playing Interview with Derek Bermel Nicolas Bacri’s Ophelia’s Tears The Quarter-Tone MARIAM ADAM Extended Clarinet & BERGINALD RASH THE CLARINETISTS OF CHINEKE! TO DESIGN OUR NEW CLARINET MOUTHPIECE WE HAD TO GO TO MILAN “I am so happy to play the Chedeville Umbra because it is so sweet, dark, so full of colors like when you listen to Pavarotti. You have absolutely all kind of harmonics, you don’t have to force or push, and the vibration of the reed, the mouthpiece, the material, it’s connected with my heart.” Milan Rericha – International Soloist, Co-founder RZ Clarinets The New Chedeville Umbra Clarinet Mouthpiece Our new Umbra Bb Clarinet Mouthpiece creates a beautiful dark sound full of rich colors. Darker in sound color than our Elite model, it also has less resistance, a combination that is seldom found in a clarinet mouthpiece. Because it doesn’t add resistance, you will have no limits in dynamics, colors or articulation. Each mouthpiece is handcrafted at our factory in Savannah Georgia Life Without Limits through a combination of new world technology and old world craftsmanship, and to the highest standards of excellence. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] hope everyone is remaining safe and healthy during the EDITORIAL BOARD COVID-19 pandemic. Although the pandemic has changed Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, our lives in ways we could not have imagined just a short Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder time ago, inspiring musical and technological creativity is keeping us all connected. -

P.1.1 Publikacija Un

UNIVERZITET UMETNOSTI U BEOGRADU UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS IN BELGRADE 2007 BEOGRAD BELGRADE UREDNICI | Andrija \uki}, Svetozar Rapaji}, Stjepan Fileki SARADNICI | Bojana Buri}, dr Zoran Gavri}, dr Sowa Marinkovi} FOTOGRAFIJE | Dragan Mirkovi}, Miroslav Joli} (str. 4, 5) LIKOVNI UREDNIK | Danijela Paracki PREVOD NA ENGLESKI | Ksenija Todorovi} LEKTOR | Biqana Spremo Popovi} [TAMPA | TK MONT d.o.o., Beograd TIRA@ | 500 primeraka OVA PUBLIKACIJA SE IZDAJE POVODOM PROSLAVE 50 GODINA UNIVERZITETA UMETNOSTI U BEOGRADU THIS PUBLICATION IS PRINTED ON THE OCCASION OF THE FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS IN BELGRADE SADR@AJ Gaudeamus | 05 CONTENTS Prvi univerziteti u Evropi Iz istorije kulture moderne Srbije | 06 Za{to slavimo 50 godina 05 | Gaudeamus Univerziteta umetnosti u Beogradu? | 16 07 | First Universities in Europe Od po~etaka umetni~kog obrazovawa u Srbiji From the Cultural History of Modern Serbia do Univerziteta umetnosti | 24 17 | Why do we Celebrate Fifty Years Interdisciplinarne studije of the University of the Arts in Belgrade? Univerziteta umetnosti u Beogradu | 36 25 | From the Beginnings of Art Education in Serbia Rektori i prorektori Univerziteta umetnosti | 46 to the University of the Arts Kontakti | 58 37 | Interdisciplinary Studies 47 | Rectors and Vice-Rectors of the University of the Arts in Belgrade 59 | Contacts UNIVERZITET UMETNOSTI U BEOGRADU PRVI UNIVERZITETI U EVROPI IZ ISTORIJE KULTURE MODERNE SRBIJE UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS IN BELGRADE FIRST UNIVERSITIES IN EUROPE FROM THE CULTURAL HISTORY OF MODERN SERBIA 1303. osnovan Univerzitet u Rimu. 1346. osnovan Univerzitet u Pragu. 1365. osnovan Univerzitet u Be~u. 1383. osnovan Univerzitet u Krakovu. 1388. osnovan Univerzitet u Kelnu. -

2011 Charlotte, Nc

3 9 THANNUALNATIONALFLUTEASSOCIATIONCONVENTION OUGH D R IV TH E Y R T S I I T N Y U MANY FLUTISTS, ONE WORLD AUGUST 11–14, 2011 CHARLOTTE, NC Professional flute cases All Wiseman cases are hand made by craftsmen in England fr om the finest materials. All instrument combinations supplied – choose fr om a range of lining colours. Wiseman Cases London 7 Genoa Road, London, SE20 8ES, England [email protected] 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 www.wisemancases.com nfaonline.org 3 4 nfaonline.org cTable of Contents c Letter from the Chair 9 Welcome Letter from the Governor of North Carolina 12 Proclamation from the Mayor of Charlotte 13 Officers, Directors, and Committees 16 Past Presidents and Program Chairs 22 Previous Competition Winners and Commissions 26 Previous Award Recipients 32 Instrument Security Room Information and General Rules and Policies 34 Acknowledgments 36 2011 NFA Lifetime Achievement Awards 40 2011 National Service Award 42 NFA Special Publications 46 General Hours and Information 50 Schedule of Events 51 Programs 78 Guide to Convention Exhibits 200 2011 NFA Exhibitors 201 Exhibit Hall Booth Directory 202 Exhibit Hall and Meeting Rooms Floorplans 203 Westin Hotel Directory 204 NFA Commercial Members Exhibiting in 2011 205 NFA Commercial Members Not Exhibiting in 2011 218 Honor Roll of Donors 219 NFA 2011 Convention Participants 222 Schedule of Events At-a-Glance 273 Index of Music Performed 278 NFA 2012 Convention: Las Vegas, Nevada 300 Competitions for Convention 2012 301 Advertiser Index 304 Please visit nfaonline.org to fill out the post-convention questionnaire. Please address all inquiries and correspondence to the national office: The National Flute Association, Inc. -

Beograd 2020

International competition D A V O R I N J E N K O BEOGRAD 2020 ŽIRI/JURY A-Z DIMITROV SAVA/DŽOMBA MARKO/ FASBENDER KRISTINA/ GAVRIĆ DEJAN/ JANKECH ALEKSANDAR/ JANKOVIĆ NENAD/ JOVANOVIĆ LJUBIŠA/ KIŠ ŠAMU/ LAZAREVSKI VLADIMIR/ LEVAI AKSIN LAURA/ LUBOMIROVA IVA/ MARKOVIĆ VUJANOVIĆ JASNA/ MILOŠEVIĆ KATARINA/ MILOŠEVSKI MARJAN/ POPOVIĆ OGNJEN/ PUŠKAŠ VLADIMIR / SAVIĆ MILAN/ VUKELIĆ BOJAN/ ZUPAN ANDREJ/ ŽIVKOVIĆ ANDREA 2 INDEX FLAUTA/FLUTE 9 KLARINET / CLARINET 44 OBOA/OBOE 59 FAGOT/BASSON 69 SAKSOFON/SAXOPHONE 76 3 INDEX A Č ABRAM NEŽA 82 ČABRILO NAĐA 60 GLUŠICA VASILIJE 79 AHNE SUMIN 39 ČEMAŽAR ANIKA 30 GOVEKAR GREGOR 46 ALEGRO MARUŠA 39 ČOVIĆ PETRA 21 GREGOVIĆ PETRA 25 ALIVOJVODIĆ IVONA 14 ČPAJAK SOFIJA 45 GRGIĆ UROŠ 21 ANĐELKOVIĆ ANASTASIJA 45 ČRNUGELJ METKA 30 GROM JAKOB 69 ANĐELKOVIĆ DISA 35 GUBENŠEK LUKA 46 ANTIĆ ANDREJA 20 GVOZDENOVIĆ ANDRIJANA 31 Ć ANTIĆ ANJA 64 ĆUMUROVIĆ BOJAN 57 ARNAUTOVIĆ DARIJA 51 H ARSIĆ NEVENA 62 HASANOVIĆ HENA 21 D HEGEDUŠ DOROTEJA 31 DANIKOV MILICA 15 B HOROVA YOANA 25 DAVIDOVIĆ LUKA 77 BAJO MIA 60 DESPIĆ SOFIJA 65 BALINT ROBERT 73 DOKŠA LORENA 57 I BANKO GREGOR 48 DORIĆ NATALIJA 30 ILIĆ ŽELJKO 82 BARAC MIHAJLO 71 DRAGIČEVIĆ ANAMARI 65 ILIJIĆ MAŠA 59 BAZNIK ANA 45 DRSTVENŠEK LEON 48 IVANČOV MARIO 73 BECIĆ LUCIJA 14 DVOŠTANSKI SOFIJA 45 IVANOVA ANTOANETA 15 BECK KLARA 65 BEGIĆ JAKOV 20 J BIBIN MILA 30 Đ ĐAK ANĐELIJA 30 JAKOLIČ TOBIJA 79 BIZJAK ARON 77 JAZBINŠEK ALJAŽ 57 BLAGOJEVIĆ BOGDAN 77 ĐORĐEVIĆ LAZAR 84 ĐORĐEVIĆ PETRA 57 JEKIĆ LAZAR 71 BLAGOJEVIĆ JOVANA 25 JEKIĆ MINA 31 BLAŽIĆ MATEJA 82 ĐUKANOVIĆ LAZAR -

Djwind 2010.Pdf

REZULTATI TAKMIčENJA U toku trajanja Međunarodnog takmičenja Davorin Jenko, plasman takmičara za svaku kategoriju biće dostupan na internetu nakon objavljivanja zvaničnih rezultata na mestu održavanja takmičenja. Rezultati, vesti i zvanična obaveštenja biće ažurirani svakodnevno na zvaničnom sajtu, u okviru sekcije Takmičenje. COMPETITION RESULTS During the International Competition Davorin Jenko the final results for the categories will be available online after the official announcement at the place of the competition. The results, news and official acknowledgments will be available on the official web site, under Competition section. www.msdjenko.edu.rs Организатор такмичења Музичка школа Даворин Јенко, Београд Competition Organizer Music School Davorin Jenko, Belgrade Покровитељ такмичења Министарство просвете Републике Србије Under Patronage of Ministry of Education of the Republic of Serbia SADRŽAJ CONTENTS 04 Index 06 KLARINET / CLARINET 14 HORNA / HORNE 18 TROMBON / TROMBONE 20 TUBA / TUBE 21 TRUBA / TRUMPET 28 FAGOT / BASSOON 30 SAKSOFON / SAXOPHONE 34 OBOA / OBOE 37 FLAUTA / FLUTE 57 KAMERNI ANSAMBLI / CHAMBER ENSEMBLES * Kako bi se izbegle greške prilikom štampanja diploma, molimo da proverite svoje podatke i eventualne korekcije prijavite sekretaru takmičenja In order to avoid mistakes in Diploma printing, please check your data and report correction to the Competition Secretary. * Ukoliko nije naznačeno, muzička škola je iz Srbije. Unless it is not assigned, the Music School is from Serbia. * Takmičenje kamernih ansambala -

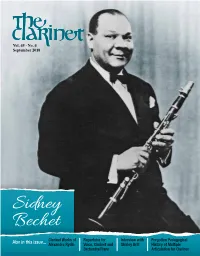

Sidney Bechet Clarinet Works of Repertoire for Interview with Forgotten Pedagogical Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 4 September 2018 Sidney Bechet Clarinet Works of Repertoire for Interview with Forgotten Pedagogical Also in this issue... Alexandre Rydin Voice, Clarinet and Shirley Brill History of Multiple Orchestra/Piano Articulation for Clarinet D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear Members and Jessica Harrie Friends of the International Clarinet Association: [email protected] s I write this message just days after the conclusion of EDITORIAL BOARD ClarinetFest® 2018, I continue to marvel at the fantastic Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, festival held on the beautiful Belgian coast of Ostend. We Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder are grateful to our friends Eddy Vanoosthuyse, artistic Adirector of ClarinetFest® 2018, and the Ostend team and family of MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR the late Guido Six – Chantal Six Vandekerckhove, Bert Six and Gaby Gregory Barrett – [email protected] Six – who together organized a truly extraordinary and memorable festival featuring artists from over 55 countries. AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR The first day alone contained an amazing array of concerts Chris Nichols – [email protected] including an homage to the legendary Guido Six by the Claribel Clarinet Choir, followed by the Honorary Member concert featuring Caroline Hartig GRAPHIC DESIGN Karl Leister, Luis Rossi, Antonio Saiote and the newest ICA honorary Karry Thomas Graphic Design member inductee, Charles Neidich. Later that evening was the [email protected] world premiere of the Piovani Clarinet Concerto with the Brussels Philharmonic, performed by Artistic Director Eddy Vanoosthuyse. -

FACTA UNIVERSITATIS UNIVERSITY of NIŠ ISSN 2466 – 2887 (Print) ISSN 2466 – 2895 (Online) Series COBISS.SR-ID 218522636 Visual Arts and Music Vol

CMYK K Y M C FACTA UNIVERSITATIS UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ ISSN 2466 – 2887 (Print) ISSN 2466 – 2895 (Online) Series COBISS.SR-ID 218522636 Visual Arts and Music Vol. 6, No 1, 2020 Contents UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ OF UNIVERSITY Johannis Tsoumas FACTA UNIVERSITATIS PLASTIC WASTE AS BOTH SOURCE OF INSPIRATION AND MEDIUM FOR CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS .................................................................................1 Series VISUAL ARTS AND MUSIC Sonja Cvetković o ORCHESTRAL PRACTICE IN NIŠ AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR – Vol. 6, N 1, 2020 FROM THE MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF THE NIŠ NATIONAL THEATER TO THE NIŠ SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA (1953–1965) .............................................19 Neda Nikolić INSTRUMENTAL THEATER IN THE WORKS OF MAURICIO KAGEL, GEORGES APERGHIS AND HEINER GOEBBELS ........33 1, 2020 Igor Nikolić, Slobodan Kodela o INTEGRAL ASPECTS OF HARMONIC HEARING IN THE PROCESS OF SIGHT-SINGING .....................................................................49 Vol. 6, N Vol. Marija R. Marković, Anastasija S. Mamutović, Zorica Č. Stanisavljević Petrović SOME ASPECTS OF REFORM AND CHANGE IN THE SYSTEM OF SECONDARY MUSIC SCHOOLS - ANALYSIS OF RELEVANT LITERATURE .................................................................61 Vesna Zdravković, Ivana Đorđević NURTURING CHOIR SINGING AMONG PRESCHOOL CHILDREN ....................73 Visual Arts and Music Visual Series FACTA UNIVERSITATIS • UNIVERSITATIS FACTA C M Y K K Y M C CMYK K Y M C Scientific JournalFACTA UNIVERSITATIS UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ Univerzitetski trg 2, 18000 Niš, Serbia Phone: -

Novi Zvuk 51.Pdf

Department of Musicology Faculty of Music International Journal of Music Belgrade, I/2018 ISSN 0354-818X = New Sound UDC 78:781(05) COBISS.SR-ID 102800647 International Journal of Music Belgrade, I/2018 Publisher: Department of Musicology Faculty of Music Kralja Milana 50, 11000 Belgrade Editorial Board: Mirjana Veselinović-Hofman Ph.D. (Editor-in-chief) Vesna Mikić Ph.D. (Deputy editor-in-chief) Academician Dejan Despić Sonja Marinković Ph.D. Ana Kotevska M.A. Miloš Zatkalik M.A. Marcel Cobussen Ph.D. (The Netherlands) Pierre Albert Castanet Ph.D. (France) Chris Walton Ph.D. (South Africa/Switzerland) Eduardo R. Miranda Ph.D. (Brazil/UK) Nico Schüler Ph.D. (Germany/USA) Cover design: Jovana Ćika Novaković Secretary of the Editorial Board: Ivana Miladinović Prica Editorial Board and Office: Faculty of Music Kralja Milana 50, 11000 Belgrade E-mail: [email protected] www.newsound.org.rs The Journal is published semestrally. The Journal is classified in ERIH – European Reference Index for the Humanities CONTENTS CONVERSATIONS Jelena Novak Music That Knows Where It’s Going. Conversation with Tom Johnson ...... 1 STUDIES Nice Fracile The Phonographic Recordings of Traditional Music Performed by Serbian Prisoners of War (1915–1918) ..................................................................... 17 Ivana Vesić, Vesna Peno The Structural Transformation of the Sphere of Musical Amateurism in Socialist Yugoslavia: A Case Study of the Beogradski Madrigalisti Choir ... 43 Bogumila Mika Music of Karol Szymanowski in the Intertextual Dialogue ......................... 64 INTERPRETATIONS Geraldine Finn Panic at the Proms (perhaps the explanation lies in his background) .......... 83 TRIBUTE TO PROF. DR. ROKSANDA PEJOVIĆ Ivana Perković Narrative Monologue and (Internal) Dialogue: In Memory of Roksanda Pejović (1929–2018) ................................................................