Ed 422 021 Author Institution Available from Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lexile Framework® for Reading Matching Students to Text!

8068528 The Lexile Framework® for Reading Matching students to text! Matching students to texts at appropriate levels helps to increase their confidence, competence, and control over the reading process. The Lexile Framework is a reliable and tested tool designed to bridge two critical aspects of student reading achievement — levelling text difficulty and assessing the reading skills of each student. SCHOOL YEAR LEXILE LEVEL BENCHMARK LITERATURE SAMPLE TEXT PASSAGES The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1530 Strange Objects Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray 1270 When the Minister for National Heritage engaged me to translate the manuscript which Strange Objects by Gary Crew 1200 appears for the first time in this paper today, I expected the task would be purely academic. 1200L– War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy 1200 Naturally, I was honoured to be undertaking the translation of such an important work, and eager to provide as accurate an interpretation of the text as I could, but nothing could Great Expectations by Charles Dickens 1200 12 1700L have prepared me for the human element, the personality of the writer. Fired Up by Sarah Ell 1180 The Wind in the Willows Animal Farm by George Orwell 1170 ‘Look here,’ he went on, ‘this is what occurs to me. There’s a sort of dell down there in front The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells 1170 of us, where the ground seems all hilly and humpy and hummocky. We’ll make our way Diary Z by Stephanie McCarthy 1140 down into that, and try and find some sort of shelter, a cave or hole with a dry floor to it, out of the snow and the wind, and there we’ll have a good rest before we try again, for we’re The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame 1140 11 1100L both of us pretty dead beat. -

Surprised by Joy: Children, Text and Identity

The Seventh Royale Ormsby Martin Lecture 2000 Surprised by Joy: Children, Text and Identity Maurice Saxby The Royale Ormsby Martin Lecture is administered by the Anglican Education Commission, Diocese of Sydney (a division of Anglican Youthworks) on behalf of the trustees: the Archbishop of Sydney, the Dean of Sydney and the Director of Education 1 Maurice Saxby Maurice Saxby, who was trained at Balmain Teacher’s College but went on to complete an Honours Degree in English from Sydney University as an evening student, believes passionately in the power of literature to enhance life, both for children and adults. He has taught infants, primary and secondary school students, but his career has been mainly as a lecturer in tertiary institutions. He retired as Head of the English Department at Kuring-gai College of Advanced Education. He has lectured extensively in children’s literature both in Australia and overseas including England, America, Germany, Japan and China. Maurice was the first National President of the Children’s Book Council of Australia and has served on judging panels for children’s literature many times in Australia; and he is the only Australian to have been selected as a juror for the prestigious international Hans Andersen Awards. He has received the Dromkeen Medal, the Lady Cutler Award and an Order of Australia for his services to children’s literature. Maurice’s publications range from academic works such as Offered to Children: A History of Australian Children’s Literature 1841–1941; Give them Wings: The Experience of Children’s Literature and Teaching Literature to Adolescents. -

Middle Years (6-9) 2625 Books

South Australia (https://www.education.sa.gov.au/) Department for Education Middle Years (6-9) 2625 books. Title Author Category Series Description Year Aus Level 10 Rules for Detectives MEEHAN, Adventure Kev and Boris' detective agency is on the 6 to 9 1 Kierin trail of a bushranger's hidden treasure. 100 Great Poems PARKER, Vic Poetry An all encompassing collection of favourite 6 to 9 0 poems from mainly the USA and England, including the Ballad of Reading Gaol, Sea... 1914 MASSON, Historical Australia's The Julian brothers yearn for careers as 6 to 9 1 Sophie Great journalists and the visit of the Austrian War Archduke Franz Ferdinand aÙords them the... 1915 MURPHY, Sally Historical Australia's Stan, a young teacher from rural Western 6 to 9 0 Great Australia at Gallipoli in 1915. His battalion War lands on that shore ready to... 1917 GARDINER, Historical Australia's Flying above the trenches during World 6 to 9 1 Kelly Great War One, Alex mapped what he saw, War gathering information for the troops below him.... 1918 GLEESON, Historical Australia's The story of Villers-Breteeneux is 6 to 9 1 Libby Great described as wwhen the Australians held War out against the Germans in the last years of... 20,000 Leagues Under VERNE, Jules Classics Indiana An expedition to destroy a terrifying sea 6 to 9 0 the Sea Illustrated monster becomes a mission involving a visit Classics to the sunken city of Atlantis... 200 Minutes of Danger HEATH, Jack Adventure Minutes Each book in this series consists of 10 short 6 to 9 1 of Danger stories each taking place in dangerous situations. -

Relationships to the Bush in Nan Chauncy's Early Novels for Children

Relationships to the Bush in Nan Chauncy’s Early Novels for Children SUSAN SHERIDAN AND EMMA MAGUIRE Flinders University The 1950s marked an unprecedented development in Australian children’s literature, with the emergence of many new writers—mainly women, like Nan Chauncy, Joan Phipson, Patricia Wrightson, Eleanor Spence and Mavis Thorpe Clark, as well as Colin Thiele and Ivan Southall. Bush and rural settings were strong favourites in their novels, which often took the form of a generic mix of adventure story and the bildungsroman novel of individual development. The bush provided child characters with unique challenges, which would foster independence and strength of character. While some of these writers drew on the earlier pastoral tradition of the Billabong books,1 others characterised human relationships to the land in terms of nature conservation. In the early novels of Chauncy and Wrightson, the children’s relationship to the bush is one of attachment and respect for the environment and its plants and creatures. Indeed these novelists, in depicting human relationships to the land, employ something approaching the strong Indigenous sense of ‘country’: of belonging to, and responsibility for, a particular environment. Later, both Wrightson and Chauncy turned their attention to Aboriginal presence, and the meanings which Aboriginal culture—and the bloody history of colonial race relations— gives to the land. In their earliest novels, what is strikingly original is the way both writers use bush settings to raise questions about conservation of the natural environment, questions which were about to become highly political. In Australia, the nature conservation movement had begun in the late nineteenth century, and resulted in the establishment of the first national parks. -

Masculine Caregivers in Australian Children's Fictions 1953-2001

Chapter 3 Literary Reconfigurations of Masculinity I: Masculine caregivers in Australian children's fictions 1953-2001 'You're a failure as a parent, Joe Edwards!' Mavis Thorpe ClarkThe Min-Min (1966:185) It is easy to understand why men who grew up at a time when their fathers were automatically regarded as the head of the household and the breadwinner should feel rather threatened by the contemporary challenge to those central features of traditional masculine status ... Hugh Mackay Generations (1997:90) As cultural formations produced for young Australian readers, the children's fictions discussed in this chapter offer a diachronic study of literary processes employed to reconfigure schemas of adult masculinities.1 The pervasive interest in the transformation of Australian society's public gender order and its domestic gender regimes in the late twentieth century is reflected in children's fictions where reconfigurations of masculine subjectivities are represented with increasing narrative and discursive complexity. The interrogation of masculinity—specifically as fathering/caregiving—shifts in importance from a secondary level story in post-war realist fictions to the focus of the primary level story by the century's end. Thematically its significance changes too, from the reconfigurations of social relations in the domestic sphere that subverts the doxa of patriarchal legitimacy, to narratives that problematise masculinity in the public gender An earlier version of this chapter is published in Papers: Explorations into Children's Literature, 9: 1 (April 1999): 31-40. order. From the mid-1960s, feminist epistemologies provide the impetus for the first reconfiguration in the representations of fathering masculinities that challenges traditional patriarchy. -

Sacs Secondary Reading Lists

Sacs Secondary Reading Lists ST ANDREW’S CATHEDRAL SCHOOL SECONDARY BOOK LISTS Aboriginal stories Action and adventure Biography and autobiography Christian Classics Crime Dystopian Fantasy Graphic novels Historical fiction Humorous stories Love and romance Middle School reading list Multicultural stories Non fiction Science fiction Senior reading list Short stories (online) Sports Thrillers War stories World literature St Andrew’s Cathedral School Secondary Reading Lists 2015 Page 1 ABORIGINAL STORIES Definition: fiction books written by Aboriginal authors. Author Title or Series Behrendt, Larissa Home Coleman, Dylan Mazin Grace Fran, Dobbie Whisper Paper bags and dreams Frankland, Richard J. Walking the boundaries Heiss, Anita Who am I? The diary of Mary Talence, Sydney, 1937 (or any other title) Leane, Jeanine Purple threads Lucashenko, Melissa Killing Darcy McDonald, Meme & My girragundji Prior, Boori The Binna Binna Man Njunjul the sun Mudrooroo (Johnson, Master of the ghost dreaming series Colin) Wild cat falling Norrington, Leonie The Barrumbi kids series Watson, Nicole The boundary Wharton, Herb Yumba days Wimot, Eric Pemulwuy: the Rainbow Warrior St Andrew’s Cathedral School Secondary Reading Lists 2015 Page 2 ABORIGINAL PICTURE BOOKS Definition: junior picture books written by Aboriginal authors. Author Title or Series Adams, Jeanie Going for oysters Pigs and honey Bancroft, Bronwyn Possum & Wattle or any other title Barunga, Albert About this little devil and this little fella Fry, Chris Nardika learns to make a spear Greene, -

Submission to the Productivity Commission Re Copyright Restrictions on the Parallel Importation of Books

SUBMISSION TO THE PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION RE COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS ON THE PARALLEL IMPORTATION OF BOOKS 14 January, 2009 As a peak Australian voluntary organisation whose membership represents authors, illustrators, publishers, booksellers, teachers, librarians, teacher-librarians and parents, the Children's Book Council of Australia would like to express its objection to changes to present provisions of the Copyright Act that restrict parallel importation. Australia has a vibrant book industry, including the publication of many books for children. We see these books as a major enculturating force – they help Australian children to discover and celebrate who we are and what is important to us; they tell us our own unique stories in our own language/s, asking us to critically examine ourselves and our way of life. Every year, in schools around Australia, tens of thousands of Australian children celebrate the best of Australian children's literature, culminating in the CBCA Book of the Year Awards followed by Book Week. Australian award-winning books are written by new as well as established authors. With some of these books, Australian publishers have taken a chance in their publication; a chance which may not have been taken if parallel importation restrictions had been lifted. Australian authors feature prominently in international awards and honour lists because of the high quality of their work. Before succeeding overseas, all of these authors have first been published by Australian publishers. Some (but not all) award- winning Australian -

A Writer's Calendar

A WRITER’S CALENDAR Compiled by J. L. Herrera for my mother and with special thanks to Rose Brown, Peter Jones, Eve Masterman, Yvonne Stadler, Marie-France Sagot, Jo Cauffman, Tom Errey and Gianni Ferrara INTRODUCTION I began the original calendar simply as a present for my mother, thinking it would be an easy matter to fill up 365 spaces. Instead it turned into an ongoing habit. Every time I did some tidying up out would flutter more grubby little notes to myself, written on the backs of envelopes, bank withdrawal forms, anything, and containing yet more names and dates. It seemed, then, a small step from filling in blank squares to letting myself run wild with the myriad little interesting snippets picked up in my hunting and adding the occasional opinion or memory. The beginning and the end were obvious enough. The trouble was the middle; the book was like a concertina — infinitely expandable. And I found, so much fun had the exercise become, that I was reluctant to say to myself, no more. Understandably, I’ve been dependent on other people’s memories and record- keeping and have learnt that even the weightiest of tomes do not always agree on such basic ‘facts’ as people’s birthdays. So my apologies for the discrepancies which may have crept in. In the meantime — Many Happy Returns! Jennie Herrera 1995 2 A Writer’s Calendar January 1st: Ouida J. D. Salinger Maria Edgeworth E. M. Forster Camara Laye Iain Crichton Smith Larry King Sembene Ousmane Jean Ure John Fuller January 2nd: Isaac Asimov Henry Kingsley Jean Little Peter Redgrove Gerhard Amanshauser * * * * * Is prolific writing good writing? Carter Brown? Barbara Cartland? Ursula Bloom? Enid Blyton? Not necessarily, but it does tend to be clear, simple, lucid, overlapping, and sometimes repetitive. -

The Development of Fantasy Illustration in Australian Children's Literature

The University of Tasmania "THE SHADOW LINE BETWEEN REALITY AND FANTASY": THE DEVELOPMENT OF FANTASY ILLUSTRATION IN AUSTRALIAN CHILDREN'S LITERATURE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Degree for Master of Education. Centre of Education by Irene Theresa Gray University of Tasmania December 1985. Acknowledgments I wish to thank the following persons for assistance in the presentation of this dissertation: - Mr. Hugo McCann, Centre for Education, University of Tasmania for his encouragement, time, assistance and critical readership of this document. Mr. Peter Johnston, librarian and colleague who kindly spent time in the word processing and typing stage. Finally my husband, Andrew whose encouragement and support ensured its completion. (i) ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to show that accompanying a development of book production and printing techniques in Australia, there has been a development in fantasy illustration in Australian children's literature. This study has identified the period of Australian Children's Book Awards between 1945 - 1983 as its focus, because it encompassed the most prolific growth of fantasy-inspired, illustrated literature in Australia and • world-wide. The work of each illustrator selected for study either in storybook or picture book, is examined in the light of theatrical and artistic codes, illustrative traditions such as illusion and decoration, in terms of the relationships between text and illustration and the view of childhood and child readership. This study. has also used overseas literature as "benchmarks" for the criteria in examining these Australian works. This study shows that there has been a development in the way illustrators have dealt with the landscape, flora and fauna, people, Aboriginal mythology and the evocation and portrayal of Secondary Worlds. -

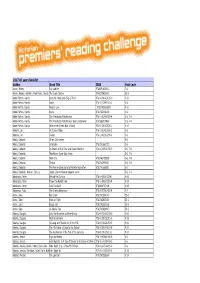

FINAL 2017 All Years Booklist.Xlsx

2017 All years Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Aaron, Moses Lily and Me 9780091830311 7-8 Aaron, Moses (reteller); Mackintosh, David (ill.)The Duck Catcher 9780733412882 EC-2 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 978-0-330-42185-0 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie 978-1-74299-010-1 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law : 9781742624280 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania 9781742990188 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker 978-1-86291-920-4 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker Goes Undercover 9781862919488 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 978-0-330-42526-1 9-10 Abdulla, Ian As I Grew Older 978-1-86291-183-3 5-6 Abdulla, Ian Tucker 978-1-86291-206-9 5-6 Abela, Deborah Ghost Club series 5-6 Abela, Deborah Grimsdon 9781741663723 5-6 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 978-1-74051-765-2 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Max Remy Super Spy series 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah New City 9781742758558 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Teresa 9781742990941 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Remarkable Secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen 9781741660951 5-6 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny Jasper Zammit Soccer Legend series 5-6, 7-8 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 978-1-4063-0029-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 978-1-4063-0028-4 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9780060737108 9-10 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Acton, Sara Ben Duck 9781741699142 EC-2 Acton, Sara Hold on Tight 9781742833491 EC-2 Acton, Sara Poppy Cat 9781743620168 EC-2 Acton, Sara As Big As You 9781743629697 -

Walter Mcvitty Books Publisher's Archive

A Guide to the Walter McVitty Books Publisher’s Archive The Lu Rees Archives The Library University of Canberra October 2002 Scope and Content Note • Papers • 1984 – 1997 • 25 boxes • Series 6 (Publishers) is restricted for 15 years. (2003-2018) • Series 9, (Finance and Sales) is restricted for 15 years. (2003-2018) These papers were donated to the Lu Rees Archives in 2000 under the Cultural Gifts Program. The papers are a complete record of the publishing company ‘Walter McVitty Books’, from its inception in 1985 until it’s sale in 1997. They are unique because this company was the only publisher to exclusively publish Australian children’s books. The papers include correspondence, reviews, artwork, contracts, awards, financial statements, manuscripts, book dummies and publicity materials. The major correspondents are the authors and illustrators, especially Colin Thiele and John Marsden; other publishers, and book clubs and associations. This finding aid was prepared by Management of Archives students Kerri Kemister, Wendy-Anne Quarmby and Lisa Roulstone, under the supervision of Professor Belle Alderman. Walter McVitty Biographical Note Prepared by: Cathie Bartley, Karen Ottoway and Amanda Rebbeck. Teacher, teacher librarian, tertiary lecturer, critic, editor, author and publisher Walter McVitty was born in Melbourne in 1934 and has been involved in the field of children’s literature for over four decades. He taught in schools in Victoria and worked overseas for five years before undertaking a librarianship course at Melbourne Teachers College in 1962. He was a teacher librarian in Victoria for six years, then Senior Lecturer in children's literature at Melbourne Teachers College for fifteen years before establishing his own small publishing company, Walter McVitty Books, with his wife Lois in 1985. -

The Children's Book Council of Australia Book of the Year Awards

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — CONTENTS Page BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — 1981 . 2 BOOK OF THE YEAR: OLDER READERS . .. 7 BOOK OF THE YEAR: YOUNGER READERS . 12 VISUAL ARTS BOARD AWARDS 1974 – 1976 . 17 BEST ILLUSTRATED BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 17 BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD: EARLY CHILDHOOD . 17 PICTURE BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 20 THE EVE POWNALL AWARD FOR INFORMATION BOOKS . 28 THE CRICHTON AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 32 CBCA AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 33 CBCA BOOK WEEK SLOGANS . 34 This publication © Copyright The Children’s Book Council of Australia 2021. www.cbca.org.au Reproduction of information contained in this publication is permitted for education purposes. Edited and typeset by Margaret Hamilton AM. CBCA Book of the Year Awards 1946 - 1 THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 – From 1946 to 1958 the Book of the Year Awards were judged and presented by the Children’s Book Council of New South Wales. In 1959 when the Children’s Book Councils in the various States drew up the Constitution for the CBC of Australia, the judging of this Annual Award became a Federal matter. From 1960 both the Book of the Year and the Picture Book of the Year were judged by the same panel. BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 1946 - 1981 Note: Until 1982 there was no division between Older and Younger Readers. 1946 – WINNER REES, Leslie Karrawingi the Emu John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham COMMENDED No Award 1947 No Award, but judges nominated certain books as ‘the best in their respective sections’ For Very Young Children: MASON, Olive Quippy Illus.