Wellington Shire Heritage Study: Stage 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpine National Park ‐ Around Heyfield, Licola and Dargo Visitor Guide

Alpine National Park ‐ around Heyfield, Licola and Dargo Visitor Guide The Alpine National Park stretches from central Gippsland all the way to the New South Wales border where it adjoins Kosciuszko National Park. In this south‐western section of the park you will find pleasant Snow Gum woodlands, sprawling mountain vistas, spectacular rivers and gorges, as well as rich cultural heritage ‐ from the rock scatters of the Gunaikurnai people on lofty vantage points, to grazier’s huts nestling in protected folds of the high country. Hut is a further 3 km though groves of snow gums. Built in 1940, the Getting there hut is an excellent example of bush architecture. Continue 1 km This area of the Alpine National Park is situated approximately 250‐ south east from the hut to the carpark. 320 km east of Melbourne. To get to Heyfield take Princes Highway to Traralgon, then take Traralgon‐Maffra Road. Alternatively, stay on First Falls and Moroka Gorge – 6km, 3 hours return Princes Highway to Sale and continue onto A1 to Dargo From Horseyard Flat the track crosses a footbridge over the Moroka The main access is from Licola via the Tamboritha Road, which leads River before meandering through snow gum woodland and crossing to the Howitt and Moroka Roads. wetlands on boardwalks. It follows the river downstream to the First Falls. A rock platform is an ideal viewing point to see the rushing Mountain roads are often unsealed, narrow and winding. Take care Moroka River plunging into a deep pool. as roads may be slippery and surface condition poor. -

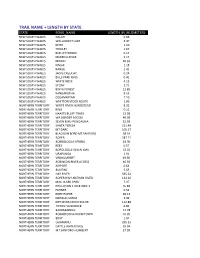

Trail Name + Length by State

TRAIL NAME + LENGTH BY STATE STATE ROAD_NAME LENGTH_IN_KILOMETERS NEW SOUTH WALES GALAH 0.66 NEW SOUTH WALES WALLAGOOT LAKE 3.47 NEW SOUTH WALES KEITH 1.20 NEW SOUTH WALES TROLLEY 1.67 NEW SOUTH WALES RED LETTERBOX 0.17 NEW SOUTH WALES MERRICA RIVER 2.15 NEW SOUTH WALES MIDDLE 40.63 NEW SOUTH WALES NAGHI 1.18 NEW SOUTH WALES RANGE 2.42 NEW SOUTH WALES JACKS CREEK AC 0.24 NEW SOUTH WALES BILLS PARK RING 0.41 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITE ROCK 4.13 NEW SOUTH WALES STONY 2.71 NEW SOUTH WALES BINYA FOREST 12.85 NEW SOUTH WALES KANGARUTHA 8.55 NEW SOUTH WALES OOLAMBEYAN 7.10 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITTON STOCK ROUTE 1.86 NORTHERN TERRITORY WAITE RIVER HOMESTEAD 8.32 NORTHERN TERRITORY KING 0.53 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAASTS BLUFF TRACK 13.98 NORTHERN TERRITORY WA BORDER ACCESS 40.39 NORTHERN TERRITORY SEVEN EMU‐PUNGALINA 52.59 NORTHERN TERRITORY SANTA TERESA 251.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY MT DARE 105.37 NORTHERN TERRITORY BLACKGIN BORE‐MT SANFORD 38.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER 287.71 NORTHERN TERRITORY BORROLOOLA‐SPRING 63.90 NORTHERN TERRITORY REES 0.57 NORTHERN TERRITORY BOROLOOLA‐SEVEN EMU 32.02 NORTHERN TERRITORY URAPUNGA 1.91 NORTHERN TERRITORY VRDHUMBERT 49.95 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROBINSON RIVER ACCESS 46.92 NORTHERN TERRITORY AIRPORT 0.64 NORTHERN TERRITORY BUNTINE 5.63 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAY RIVER 335.62 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER HWY‐NATHAN RIVER 134.20 NORTHERN TERRITORY MAC CLARK PARK 7.97 NORTHERN TERRITORY PHILLIPSON STOCK ROUTE 55.84 NORTHERN TERRITORY FURNER 0.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY PORT ROPER 40.13 NORTHERN TERRITORY NDHALA GORGE 3.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY -

19Oice 06 Lhe Mounlains JOURNAL of the MOUNTAIN DISTRICT CATTLEMEN's ASSOCIATION of VICTORIA 1983 · 84 EDITION NO

19oice 06 lhe mounlains JOURNAL OF THE MOUNTAIN DISTRICT CATTLEMEN'S ASSOCIATION OF VICTORIA 1983 · 84 EDITION NO. 8 "l9oice ol lhe mounlains Journal of the Mountain District Cattlemen's Association of Victoria Compiled by J. Commins, H. Stephenson and G. Stoney OFFICE BEARERS 1983 - 84 President J .A. Commins, Ensay Vice-Presidents C. Hodge, Valencia Creek H . Ryder, Tawonga W. Cumming, Glenmaggie Liaison Offleer G. Stoney, Mansfield Special Assignments L. Mccready, Myrtleford Sec/Treasurer C. Aston, Ensay Marketing Officer Joanne Rogers, Box 744, Bairnsdale INDEX From the President . ...... ...... ........ ........ ..... ...... ........ ·.... 2 Holmes Plain Get Together 1984 .. ........................................... 3 Vale - Mr Eric Cumming .... ...... ......................................... 3 A Sad Loss and a Message ........................... ....................... 4 For the Future .................................. .......................... 4 Study of Cattle on the High Plains ........................ ................. 8 The Old Bush Forge - at Gow's Hut ..... ..................................... 10 The Beveridge Brothers .. .. .... ..................... ... .. .. .. ....... .. 12 The Valley .. .......................... .......... ....... .................. 15 The Rumpffs ........... ... ..... ... .... .................. .. ....... .. ... 16 The Pack Horse ........... .......................... .... .. .. .. .. .. .... .. 21 Hot Billy Tea ............ ... ..... ........................................ 22 Huts and Tracks -

Latrobe River Basin January 2014

Latrobe River Basin January 2014 Introduction Southern Rural Water is the water corporation responsible for administering and enforcing the Latrobe River Basin Local Management Plan. The purpose of the Latrobe River Basin Local Management Plan is to: • document the management objectives for the system • explain to licence holders (and the broader community) the specific management objectives and arrangements for their water resource and the rules that apply to them as users of that resource • clarify water sharing arrangements for all users and the environment, including environmental flow requirements • document any limits, including water use caps, permissible consumptive volumes or extraction limits that apply to the system. Management objectives The objective of the Local Management Plan is to ensure the equitable sharing of water between users and the environment and the long-term sustainability of the resource. Water system covered The Local Management Plan covers all the rivers and creeks located within the Latrobe River Basin, which includes: Upper Latrobe Catchment Narracan Creek Catchment Moe River Catchment Frenchmans Creek Narracan Creek Bear Creek Harolds Creek Little Narracan Creek Bull Swamp Creek Hemp Hills Creek Trimms Creek Crossover Creek Loch River Dead Horse Creek McKerlies Creek Morwell River Catchment Hazel Creek Sandy Creek Billy’s Creek Loch Creek Stony Creek Eel Hole Creek Moe Main Drain Torongo River Little Morwell River Moe River Upper Latrobe River Morwell River Mosquito Creek Latrobe River Catchment O’Grady Creek Red Hill Creek Tanjil River Sassafras Creek Sassafras Creek Latrobe River Silver Creek Settlers Creek Tyers River Ten Mile Creek Seymour Creek Jacobs Creek Walkley’s Creek Shady Creek Traralgon Creek Wilderness Creek Sunny Creek The Latrobe River Basin is shown in the map below. -

Rivers and Streams Special Investigation Final Recommendations

LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL RIVERS AND STREAMS SPECIAL INVESTIGATION FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS June 1991 This text is a facsimile of the former Land Conservation Council’s Rivers and Streams Special Investigation Final Recommendations. It has been edited to incorporate Government decisions on the recommendations made by Order in Council dated 7 July 1992, and subsequent formal amendments. Added text is shown underlined; deleted text is shown struck through. Annotations [in brackets] explain the origins of the changes. MEMBERS OF THE LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL D.H.F. Scott, B.A. (Chairman) R.W. Campbell, B.Vet.Sc., M.B.A.; Director - Natural Resource Systems, Department of Conservation and Environment (Deputy Chairman) D.M. Calder, M.Sc., Ph.D., M.I.Biol. W.A. Chamley, B.Sc., D.Phil.; Director - Fisheries Management, Department of Conservation and Environment S.M. Ferguson, M.B.E. M.D.A. Gregson, E.D., M.A.F., Aus.I.M.M.; General Manager - Minerals, Department of Manufacturing and Industry Development A.E.K. Hingston, B.Behav.Sc., M.Env.Stud., Cert.Hort. P. Jerome, B.A., Dip.T.R.P., M.A.; Director - Regional Planning, Department of Planning and Housing M.N. Kinsella, B.Ag.Sc., M.Sci., F.A.I.A.S.; Manager - Quarantine and Inspection Services, Department of Agriculture K.J. Langford, B.Eng.(Ag)., Ph.D , General Manager - Rural Water Commission R.D. Malcolmson, M.B.E., B.Sc., F.A.I.M., M.I.P.M.A., M.Inst.P., M.A.I.P. D.S. Saunders, B.Agr.Sc., M.A.I.A.S.; Director - National Parks and Public Land, Department of Conservation and Environment K.J. -

West Gippsland Floodplain Management Strategy 2018

WEST GIPPSLAND CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY West Gippsland Floodplain Management Strategy 2018 - 2027 Disclaimer Acknowledgements This publication may be of assistance to you but The development of this West Gippsland the West Gippsland Catchment Management Floodplain Management Strategy has involved Authority (WGCMA) and its employees do not the collective effort of a number of individuals guarantee that the publication is without flaw and organisations. of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your Primary author – Linda Tubnor (WGCMA) particular purpose. It therefore disclaims all Support and technical input – WGCMA liability for any error, loss or other consequence Board (Jane Hildebrant, Ian Gibson, Courtney which may arise from you relying on any Mraz), Martin Fuller (WGCMA), Adam Dunn information in this publication. (WGCMA), Catherine Couling (WGCMA), Copyright and representatives from VICSES, Bass Coast Shire Council, Baw Baw Shire Council, Latrobe © West Gippsland Catchment Management City Council, South Gippsland Shire Council, Authority Wellington Shire Council, East Gippsland First published 2017. This publication is Shire Council, East Gippsland Catchment copyright. No part may be reproduced by any Management Authority, DELWP, Bunurong process except in accordance with the provisions Land Council, Gunaikurnai Land and Waters of the Copyright Act 1968. Aboriginal Corporation and Boon Wurrung Foundation. Accessibility Acknowledgement of Country This document is available in alternative formats upon request. We would like to acknowledge and pay our respects to the Traditional Land Owners and other indigenous people within the catchment area: the Gunaikurnai, The Bunurong and Boon Wurrung, and the Wurundjeri people. We also recognise the contribution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and organisations in Land and Natural Resource Management. -

EPBC Act Referral

Submission #2198 - Fingerboards Mineral Sands Project Title of Proposal - Fingerboards Mineral Sands Project Section 1 - Summary of your proposed action Provide a summary of your proposed action, including any consultations undertaken. 1.1 Project Industry Type Mining 1.2 Provide a detailed description of the proposed action, including all proposed activities. The Fingerboards Mineral Sands Project is a proposal to develop the Glenaladale mineral sands deposit (Glenaladale deposit) in East Gippsland. The Glenaladale deposit straddles East Gippsland Shire and Wellington Shire, however the project area is located entirely in East Gippsland Shire. The Glenaladale deposit contains an estimated 2.7 billion tonnes of mineralised sand and 53 million tonnes (Mt) of heavy minerals including around 12 Mt of zircon. The Fingerboards Mineral Sands Project will mine approximately 10% of the Glenaladale deposit over 20 years. Kalbar Resources will use open cut mining methods to extract 200 Mt of ore from the eastern part of the Glenaladale deposit to produce 6 Mt of heavy mineral concentrate (HMC). It is envisaged that, due to the size of the deposit, mining will continue in other areas of the deposit following the closure of the Fingerboards Mine. The ore will be fed to a mining unit plant (MUP) for slurrying and pumping to the wet concentrator plant (WCP). There the slurried ore will undergo initial onsite processing to produce HMC. The HMC will be exported for further processing into commercial products such as zircon and rutile. All overburden will be returned to the mined-out void, with the majority directly returned as mining progresses. -

Talk Wild Trout Conference Proceedings 2015

Talk Wild Trout 2015 Conference Proceedings 21 November 2015 Mansfield Performing Arts Centre, Mansfield Victoria Partners: Fisheries Victoria Editors: Taylor Hunt, John Douglas and Anthony Forster, Freshwater Fisheries Management, Fisheries Victoria Contact email: [email protected] Preferred way to cite this publication: ‘Hunt, T.L., Douglas, J, & Forster, A (eds) 2015, Talk Wild Trout 2015: Conference Proceedings, Fisheries Victoria, Department of Economic Development Jobs Transport and Resources, Queenscliff.’ Acknowledgements: The Victorian Trout Fisher Reference Group, Victorian Recreational Fishing Grants Working Group, VRFish, Mansfield and District Fly Fishers, Australian Trout Foundation, The Council of Victorian Fly Fishing Clubs, Mansfield Shire Council, Arthur Rylah Institute, University of Melbourne, FlyStream, Philip Weigall, Marc Ainsworth, Vicki Griffin, Jarod Lyon, Mark Turner, Amber Clarke, Andrew Briggs, Dallas D’Silva, Rob Loats, Travis Dowling, Kylie Hall, Ewan McLean, Neil Hyatt, Damien Bridgeman, Paul Petraitis, Hui King Ho, Stephen Lavelle, Corey Green, Duncan Hill and Emma Young. Project Leaders and chapter contributors: Jason Lieschke, Andrew Pickworth, John Mahoney, Justin O’Connor, Canran Liu, John Morrongiello, Diane Crowther, Phil Papas, Mark Turner, Amber Clarke, Brett Ingram, Fletcher Warren-Myers, Kylie Hall and Khageswor Giri.’ Authorised by the Victorian Government Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR), 1 Spring Street Melbourne Victoria 3000. November 2015 -

Monitoring River Nutrient Loads to the Gippsland Lakes 2006–07

ENVIRONMENT REPORT MONITORING RIVER NUTRIENT LOADS TO THE GIPPSLAND LAKES 2006–07 Report to the Gippsland Lakes Task Force Task RCIP EG-0607-04.018 Publication 1271 February 2009 1 MONITORING RIVER NUTRIENT LOADS TO THE GIPPSLAND LAKES 2006–07 SUMMARY bushfires in the upper catchments and to several major flood events. This report presents the results of a monitoring • Monitoring of nutrient loads immediately program designed to assess the loads of nutrients downstream of the bushfire-affected areas on the entering the Gippsland Lakes during 2006—07. EPA Thomson, Macalister, Avon and Mitchell Rivers Victoria conducted the monitoring program for the confirmed that these areas were a major source Gippsland Lakes and Catchment Task Force. of nutrients to the Gippsland Lakes. Lake The monitoring program measured the loads of the two Glenmaggie appears to have retained a main nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) entering the considerable proportion of the nutrients Gippsland Lakes from the six major rivers that drain the transported by the Macalister River following the catchment of the lakes over the 12-month period from fires, reducing the load that would have otherwise 1 July 2006 to 30 June 2007. This report describes the entered the lakes. nutrient loads contributed by the individual rivers, irrigation drains and major flood events. A number of catchments within the region were affected by major bushfires in December 2006 and a major flood (a one-in-100–year event) that commenced in June 2007 and continued into July. While the flood extended beyond the nominal study period, the magnitude of this event warranted a separate assessment of the nutrient loads over the full period of the event. -

Environmental Condition of Rivers and Streams in the Latrobe, Thomson and Avon Catchments

ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITION OF RIVERS AND STREAMS IN THE LATROBE, THOMSON AND AVON CATCHMENTS Publication 832 March 2002 1 INTRODUCTION activities have contributed to a significant change in the quantity and quality of water delivered to Lake This publication provides an overview of the Wellington and there is a significant amount of environmental condition of the rivers and streams in public concern regarding impacts on the health of the Latrobe, Thomson and Avon catchments1 (Figure the Gippsland Lakes. 1). The Latrobe and Thomson river systems, for The Latrobe, Thomson and Avon catchments contain example, contribute approximately twice the some of Victoria’s most significant river systems. nutrient inputs to the Gippsland Lakes than all other Located in the Gippsland region of Victoria, these riverine inputs. The most significant nutrient loading three river systems form the total catchment of Lake is associated with high flow events and reflects the Wellington, the western-most of the Gippsland increased surface runoff and erosion caused Lakes. The demands on these freshwater resources through land clearance and urbanisation. are considerable. Australia’s largest pulp and paper It is commonly agreed that the only long-term mill, most of the State’s power industry, much of solution for improving the condition of Lake Melbourne’s water supply and the State’s second Wellington is to significantly reduce the nutrient largest irrigation district fall within their catchment loads from the Latrobe and Thomson river systems. boundaries. Restoration of the catchments to a more sustainable Much change has occurred in these catchments land use, revegetating riparian zones and reducing since early settlement. -

Victorian Recreational Fishing Guide 2021

FREE TARGET ONE MILLION ONE MILLION VICTORIANS FISHING #target1million VICTORIAN RECREATIONAL FISHING A GUIDE TO FISHING RULES AND PRACTICES 2021 GUIDE 2 Introduction 55 Waters with varying bag and size limits 2 (trout and salmon) 4 Message from the Minister 56 Trout and salmon regulations 5 About this guide 60 Year-round trout and salmon fisheries 6 Target One Million 61 Trout and salmon family fishing lakes 9 Marine and estuarine fishing 63 Spiny crays 10 Marine and estuarine scale fish 66 Yabbies 20 Sharks, skates and rays 68 Freshwater shrimp and mussels 23 Crabs INTRODUCTION 69 Freshwater fishing restrictions 24 Shrimps and prawns 70 Freshwater fishing equipment 26 Rock lobster 70 Using equipment in inland waters 30 Shellfish 74 Illegal fishing equipment 33 Squid, octopus and cuttlefish 74 Bait and berley 34 Molluscs 76 Recreational fishing licence 34 Other invertebrates 76 Licence information 35 Marine fishing equipment 78 Your fishing licence fees at work 36 Using equipment in marine waters 82 Recreational harvest food safety 40 Illegal fishing equipment 82 Food safety 40 Bait and berley 84 Responsible fishing behaviours 41 Waters closed to recreational fishing 85 Fishing definitions 41 Marine waters closed to recreational fishing 86 Recreational fishing water definitions 41 Aquaculture fisheries reserves 86 Water definitions 42 Victoria’s marine national parks 88 Regulation enforcement and sanctuaries 88 Fisheries officers 42 Boundary markers 89 Reporting illegal fishing 43 Restricted areas 89 Rule reminders 44 Intertidal zone -

And Hinterland LANDSCAPE PRIORITY AREA

GIPPSLAND LAKES and Hinterland LANDSCAPE PRIORITY AREA Photo: The Perry River 31 GIPPSLAND LAKES AND HINTERLAND Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland AQUIFER ASSET VALUES, CONDITION AND KEY THREATS Figure 25: Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland Landscape Priority Area Aquifer Asset Shallow Aquifer The Shallow Alluvial aquifer includes the Denison and Wa De Lock Groundwater Management Areas. It has high Figure 24: Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland Landscape connectivity to surface water systems including the provision Priority Area location of base flow to rivers, such as the Avon, Thomson and Macalister. The aquifer contributes to the condition of other Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems including wetlands, The Gippsland Lakes and Hinterland landscape priority area estuarine environments and terrestrial flora. The aquifer is characterised by the iconic Gippsland Lakes and wetlands is also a very important resource for domestic, livestock, Ramsar site. The Gippsland Lakes is of high social, economic, irrigation and urban (Briagolong) water supply. The shallow environmental and cultural value and is a major drawcard aquifer of the Avon, Thomson, Macalister and lower Latrobe for tourists. A number of major Gippsland rivers (Latrobe, catchments is naturally variable in quality and yield. In many Thomson, Macalister, Avon and Perry) all drain through areas the aquifer contains large volumes of high quality floodplains to Lake Wellington and ultimately the Southern (fresh) groundwater, whereas elsewhere the aquifer can be Ocean, with the Perry River being one of the few waterways naturally high in salinity levels. Watertable levels in some in Victoria to have an intact chain of ponds geomorphology. areas have been elevated due to land clearing and irrigation The EPBC Act listed Gippsland Red Gum Grassy Woodland recharge.