Building to Survive: Suicide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

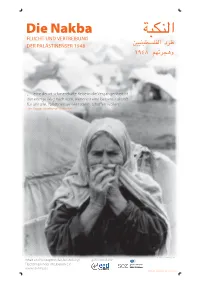

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

Note: the List Was Compiled by @Maathmusleh. It Is Possible That Some Tweeps Are Missing

Note: the list was compiled by @MaathMusleh. It is possible that some tweeps are missing. It is also possible that there are minor mistakes in the data, besides the missing data. If you locate any missing information or wrong data, please contact @MaathMusleh. Note: Data in the Original village/city column is linked to a page with information about it. Note: Twitter handlers are linked to the personal blog/site of the person Note: the list of each continent is arranged by the number of followers (top to bottom) Note: presence of tweeps on the list does not necessarily mean endorsement to their political views; it is simply a fact sheet list Palestinians on Twitter Worldwide (Arab World (122), Asia (1), Australia (6), Central & South America (13), Europe (27), North America (87), Palestine (335)) Twitter Handler Country City/Village/RC* Original Village/City Arab World TamimBarghouti Egypt Cairo DeirGhassaneh khanfarw Qatar Doha AlRama AzmiBishara Qatar Doha Nazareth MouridBarghouti Egypt Cairo DeirGhassaneh AlSwairky KSA Riyadh jamalrayyan Qatar Doha TulKarem YZaatreh Jordan Amman Jericho Samihtoukan Jordan Amman Nablus luluderaven Egypt Cairo AlJura film_head KSA Jeddah Moabuobeid UAE Dubai Yabad iyad_elbaghdadi UAE Dubai Yafa 88Mona88 Qatar Doha Jerusalem livefromgaza Qatar Doha Majdal-Asqalan AliDahmash Jordan Amman Lydd lubzi azizdalloul Qatar Doha Gaza City docjazzmusic UAE Dubai Ellar Ammouni UAE Dubai Shaab DaoudKuttab Jordan Amman Baraah8 KSA LinaWaheeb Jordan Amman EinKarem Rdooan Egypt Cairo Yousefalawnah Kuwait Kuwait Falasteeni -

Israel's Rights As a Nation-State in International Diplomacy

Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Institute for Research and Policy המרכז הירושלמי לענייני ציבור ומדינה )ע"ר( ISRAEl’s RiGHTS as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy Israel’s Rights as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy © 2011 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs – World Jewish Congress Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 13 Tel Hai Street, Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 972-2-561-9281 Fax. 972-2-561-9112 Email: [email protected] www.jcpa.org World Jewish Congress 9A Diskin Street, 5th Floor Kiryat Wolfson, Jerusalem 96440 Phone : +972 2 633 3000 Fax: +972 2 659 8100 Email: [email protected] www.worldjewishcongress.com Academic Editor: Ambassador Alan Baker Production Director: Ahuva Volk Graphic Design: Studio Rami & Jaki • www.ramijaki.co.il Cover Photos: Results from the United Nations vote, with signatures, November 29, 1947 (Israel State Archive) UN General Assembly Proclaims Establishment of the State of Israel, November 29, 1947 (Israel National Photo Collection) ISBN: 978-965-218-100-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Overview Ambassador Alan Baker .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The National Rights of Jews Professor Ruth Gavison ........................................................................................................................................................................... 9 “An Overwhelmingly Jewish State” - From the Balfour Declaration to the Palestine Mandate -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France. -

United Nations Conciliation.Ccmmg3sionfor Paiestine

UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION.CCMMG3SIONFOR PAIESTINE RESTRICTEb Com,Tech&'Add; 1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH APPENDIX J$ NON - JlXWISHPOPULATION WITHIN THE BOUNDARXESHELD BY THE ISRAEL DBFENCEARMY ON X5.49 AS ON 1;4-,45 IN ACCORDANCEWITH THE PALESTINE GOVERNMENT VILLAGE STATISTICS, APRIL 1945. CONTENTS Pages SUMMARY..,,... 1 ACRE SUB DISTRICT . , , . 2 - 3 SAPAD II . c ., * ., e .* 4-6 TIBERIAS II . ..at** 7 NAZARETH II b b ..*.*,... 8 II - 10 BEISAN l . ,....*. I 9 II HATFA (I l l ..* a.* 6 a 11 - 12 II JENIX l ..,..b *.,. J.3 TULKAREM tt . ..C..4.. 14 11 JAFFA I ,..L ,r.r l b 14 II - RAMLE ,., ..* I.... 16 1.8 It JERUSALEM .* . ...* l ,. 19 - 20 HEBRON II . ..r.rr..b 21 I1 22 - 23 GAZA .* l ..,.* l P * If BEERSHEXU ,,,..I..*** 24 SUMMARY OF NON - JEWISH'POPULATION Within the boundaries held 6~~the Israel Defence Army on 1.5.49 . AS ON 1.4.45 Jrr accordance with-. the Palestine Gp~ernment Village ‘. Statistics, April 1945, . SUB DISmICT MOSLEMS CHRISTIANS OTHERS TOTAL ACRE 47,290 11,150 6,940 65,380 SAFAD 44,510 1,630 780 46,920 TJBERIAS 22,450 2,360 1,290 26,100 NAZARETH 27,460 Xl, 040 3 38,500 BEISAN lT,92o 650 20 16,590 HAXFA 85,590 30,200 4,330 120,520 JENIN 8,390 60 8,450 TULJSAREM 229310, 10 22,320' JAFFA 93,070 16,300 330 1o9p7oo RAMIIEi 76,920 5,290 10 82,220 JERUSALEM 34,740 13,000 I 47,740 HEBRON 19,810 10 19,820 GAZA 69,230 160 * 69,390 BEERSHEBA 53,340 200 10 53,m TOT$L 621,030 92,060 13,710 7z6,8oo . -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Palestine <Sa3ette

Palestine <Sa3ette pubUsbeb by authority No. 888 THURSDAY, 18TH MAY, 1939 497 CONTENTS Page ORDINANCE CONFIRMED Confirmation of Ordinance No. 8 of 1939 - - - 499 GOVERNMENT NOTICES ־ Termination of Appointment of Honorary Consul of Mexico at Jerusalem - 499 ־ - Appointment of Magistrates to sit as Judges of District Courts 499 Appointments, etc. ------ 499 Hours of Public Business at Nazareth - - 500 ־ Time-Table Alterations—Haifa-Acre Line 500 Loss of Tithe Receipts by Mukhtars - - - - 500 Losr> of Receipt of the Jerusalem Water Supply Department - - - 500 State Domains to be let by Auction - 500 Adjudication of Contracts - 501 Citation Orders ----- 59! Notices of the Execution Office, Tel Aviv - - - - 502 RETURNS Persons changing their Names - 506 Quarantine and Infectious Diseases Summary - - - 507 REGISTRATION OF COOPERATIVE SOCIETIES, PARTNERSHIPS, NOTICES REGARDING BANKRUPTCIES, ETC. 507 CORRIGENDA - - - - - - 509 SUPPLEMENT No. 2. The following subsidiary legislation is published in Supplement JYo. 2 which forms part of -־: this Gazette Curfew Orders under the Defence (Military Commanders) Regulations, 1938, and the Emergency Regulations, 1936, imposing Curfew on all Areas of the Jerusalem and Southern Districts, Haifa Sub-District, Galilee and Acre and Samaria Districts, except on the Municipal and Local Council Built-up Areas - 377 Road Transport (Consolidated Refineries Limited) Order, 1939, under the Road Transport Ordinance ----- 379 Order No. 64 of 1939, under the Urban Property Tax Ordinance, appointing a Non- ־ Official Member of the.Appeal Commission in the Urban Area of Tulkarm 380 (Continued) PRICE : 30 MILS. CONTENTS (G ontinued) Page Order No. 65 of 1939, under the Urban Property Tax Ordinance, appointing Non- Official Members of the Appeal Commission in the Urban Area of Jerusalem - 380 Orders Nos. -

Palestinian Conflict: UN Intervention’

Law Faculty School of International Studies Title: ‘Operation ‘Cast Lead’ as a demonstration of the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict: UN Intervention’. Thesis prior to obtaining a degree in International Studies with bilingual major in Foreign Trade Author: Mónica Trelles Muñoz Director: Dr. Esteban Segarra Cuenca, Ecuador 2014 1 DEDICATION To Adriana, On the faith that she grows up in a peaceful world; witnessing the ideal of the liberty of the Palestinian people come true. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To God, for the infinite blessings and their manifestations. To my brother Kaiser, for being the reason to move forward, for having always believed in me and for being the strength to face each challenge with cheer and optimism. To my mother Jannet, for being the best role model, for bringing me up in goodness and for supporting me unconditionally in every path of life. To Francisco, for being the best life partner, for demonstrating me his love in every circumstance, for his unparalleled support and patience. To Paúl, Johanna, Verónica, María del Carmen and Antonio for their personification of the concept of friendship, for holding me in the most complicated moments and sharing with me the best ones. I owe each one of them infinite words of gratitude and love. To my grandparents Laura and Manuel. To Enrique Santos, for having been the one who sowed interest in me for the Palestinian people. To Norma Aguirre, for her good will. To Esteban Segarra. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION…………………………………………………………………………………...2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………3 TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………….………………………………………………4 INDEX OF FIGURES AND TABLES………….…………………………………………………7 LIST OF ANNEXES..….………………………………………………………………………….8 ABSTRACT.………………………………………………………………………………………9 INTRODUCTION...………………………………………………………………………….…11 1. -

F-Dyd Programme

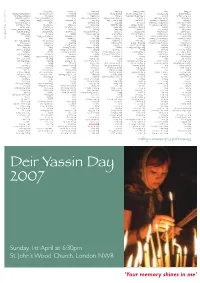

‘Your memory shines in me’ in shines memory ‘Your St. John’s Wood Church, London NW8 London Church, Wood John’s St. Sunday, 1st April at 6:30pm at April 1st Sunday, 2007 Deir Yassin Day Day Yassin Deir Destroyed Palestinian villages Amqa Al-Tira (Tirat Al-Marj, Abu Shusha Umm Al-Zinat Deir 'Amr Kharruba, Al-Khayma Harrawi Al-Zuq Al-Tahtani Arab Al-Samniyya Al-Tira Al-Zu'biyya) Abu Zurayq Wa'arat Al-Sarris Deir Al-Hawa Khulda, Al-Kunayyisa (Arab Al-Hamdun), Awlam ('Ulam) Al-Bassa Umm Ajra Arab Al-Fuqara' Wadi Ara Deir Rafat Al-Latrun (Al-Atrun) Hunin, Al-Husayniyya Al-Dalhamiyya Al-Birwa Umm Sabuna, Khirbat (Arab Al-Shaykh Yajur, Ajjur Deir Al-Shaykh Al-Maghar (Al-Mughar) Jahula Ghuwayr Abu Shusha Al-Damun Yubla, Zab'a Muhammad Al-Hilu) Barqusya Deir Yassin Majdal Yaba Al-Ja'una (Abu Shusha) Deir Al-Qasi Al-Zawiya, Khirbat Arab Al-Nufay'at Bayt Jibrin Ishwa', Islin (Majdal Al-Sadiq) Jubb Yusuf Hadatha Al-Ghabisyya Al-'Imara Arab Zahrat Al-Dumayri Bayt Nattif Ism Allah, Khirbat Al-Mansura (Arab Al-Suyyad) Al-Hamma (incl. Shaykh Dannun Al-Jammama Atlit Al-Dawayima Jarash, Al-Jura Al-Mukhayzin Kafr Bir'im Hittin & Shaykh Dawud) Al-Khalasa Ayn Ghazal Deir Al-Dubban Kasla Al-Muzayri'a Khirbat Karraza Kafr Sabt, Lubya Iqrit Arab Suqrir Ayn Hawd Deir Nakhkhas Al-Lawz, Khirbat Al-Na'ani Al-Khalisa Ma'dhar, Al-Majdal Iribbin, Khirbat (incl. Arab (Arab Abu Suwayrih) Balad Al-Shaykh Kudna (Kidna) Lifta, Al-Maliha Al-Nabi Rubin Khan Al-Duwayr Al-Manara Al-Aramisha) Jurdayh, Barbara, Barqa Barrat Qisarya Mughallis Nitaf (Nataf) Qatra Al-Khisas (Arab -

Financing Racism and Apartheid

Financing Racism and Apartheid Jewish National Fund’s Violation of International and Domestic Law PALESTINE LAND SOCIETY August 2005 Synopsis The Jewish National Fund (JNF) is a multi-national corporation with offices in about dozen countries world-wide. It receives millions of dollars from wealthy and ordinary Jews around the world and other donors, most of which are tax-exempt contributions. JNF aim is to acquire and develop lands exclusively for the benefit of Jews residing in Israel. The fact is that JNF, in its operations in Israel, had expropriated illegally most of the land of 372 Palestinian villages which had been ethnically cleansed by Zionist forces in 1948. The owners of this land are over half the UN- registered Palestinian refugees. JNF had actively participated in the physical destruction of many villages, in evacuating these villages of their inhabitants and in military operations to conquer these villages. Today JNF controls over 2500 sq.km of Palestinian land which it leases to Jews only. It also planted 100 parks on Palestinian land. In addition, JNF has a long record of discrimination against Palestinian citizens of Israel as reported by the UN. JNF also extends its operations by proxy or directly to the Occupied Palestinian Territories in the West Bank and Gaza. All this is in clear violation of international law and particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention which forbids confiscation of property and settling the Occupiers’ citizens in occupied territories. Ethnic cleansing, expropriation of property and destruction of houses are war crimes. As well, use of tax-exempt donations in these activities violates the domestic law in many countries, where JNF is domiciled. -

{PDF} Life After Ruin the Struggles Over Israels Depopulated Arab

LIFE AFTER RUIN THE STRUGGLES OVER ISRAELS DEPOPULATED ARAB SPACES 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Noam Leshem | 9781107149472 | | | | | Life after Ruin The Struggles over Israels Depopulated Arab Spaces 1st edition PDF Book Israel only made limited ground gains until the launch of Operation Changing Direction 11 , which lasted for 3 days with disputed results. While the Jewish population had received strict orders requiring them to hold their ground everywhere at all costs, [35] the Arab population was more affected by the general conditions of insecurity to which the country was exposed. This conflict was accompanied by large-scale massacres of both sides. Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. In addition to starting a process of healing the Mizrahi— Ashkenazi divide, Begin's government included Ultra-Orthodox Jews and was instrumental in healing the Zionist—Ultra-Orthodox rift. Main articles: Old Yishuv and Spanish inquisition. Dever, William In May Adolf Eichmann , one of the chief administrators of the Nazi Holocaust, was located in Argentina by the Mossad , later kidnapping him and bringing him to Israel. Expulsions also took place in Italy, affecting survivors of the original expulsion. Simon and Schuster. Chronicle of a territorial dispute". Addington The system remained in place until after Syria had 12, soldiers at the beginning of the War, grouped into three infantry brigades and an armoured force of approximately battalion size. The two main Jewish leaders, Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion , had convinced the Zionist Congress to approve equivocally the Peel recommendations as a basis for more negotiation. One of the Egyptian force's two main columns made its way northwards along the shoreline, through what is today the Gaza Strip and the other column advanced eastwards toward Beersheba.