Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milwest Dispatch April 1991

Dispatch dedicated to tfu tUstoric preservation and/or modeling of the former C^CStfP&T/Mitw. 'Lines "West' Volume 4, Issue No. 2 April 1991 - The MILWAUKEE ROAD - By Art Jacobsen History & Operations South of Tacoma, Washington - Part I - This feature has been de• major port for the region at that time. 1905 as the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. layed from previous issues due (in The NP's charter was amended on Paul Ry. of Washington. part) to a lack of research materials April 13, 1869 allowing the railroad to The NP had already been available on this area. However, - be built from Puget Sound to Portland established south from "Bcoma for MILWEST - member Tom Burg and then eastward up the Columbia over three decades, and the O- provided additional information for Gorge. Two years later 25 miles of WRR&N was not in a financial posi• this Part from various issues of the track had been built between the tion to be of much immediate help. former employee's magazine. There is present site of Kalama and the Cowlitz Therefore, the CM&StP Ry. of Wash• still much that should be covered, and River crossing (south of Vader). The ington had two choices for any poten• any member who has more research following year the track entered the tial connections in that area. The first materials available is encouraged to Yelm Prairie in the Nisqually valley; was to build its own lines, and the contact the Managing Editor for fu• and despite the financial panic and second involved acquiring existing ture "follow-up" items. -

![173-2, Discontinued] 1848 Hiawatha "Valley" Parlors 190-197 [No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5489/173-2-discontinued-1848-hiawatha-valley-parlors-190-197-no-935489.webp)

173-2, Discontinued] 1848 Hiawatha "Valley" Parlors 190-197 [No

w Route of the Super Dome Hiawathas and The Western “Cities” Domeliners BRASS CAR SIDES Passenger Car Parts for the Streamliners 1948 Hiawatha Coaches 480-497, 535-551, 600-series [No. 173-2, Discontinued] 1848 Hiawatha "Valley" Parlors 190-197 [No. 173-3, Discontinued] 1948 Pioneer Limited 16-4 "Raymond" Pullman Sleepers 27-30 [No. 173-7] 1948 Pioneer Limited 8-6-4 "River" Pullman Sleepers 19-26 [No. 173-8] The Milwaukee Road was unique among U.S. railroads in building most its own lightweight passenger cars, with the P-S sleeping cars and Super Domes being the exceptions. In 1979, BRASS CAR SIDES began producing photoetched brass HO sides for the coaches and parlors for the 1948 Twin Cities and Olympian Hiawathas, and in 1981 we added the 16-4 "Raymond" and 8-6-4 "River" sleepers for the post-war Pioneer Limited. Since 2002 we have added numerous other side sets in both HO and N-scale for the Olympian Hiawatha and the entire Milwaukee post-war fleet. These are described in separate sheets and on our web pages. REFERENCES Milwaukee Road Passenger Trains Vol. 1 by John F. Strauss, Jr. (Four Ways West) The Hiawatha Story by Jim Scribbins (University of Minnesota Press, 2007; Kalmbach 1970) Pullman-Standard Library Vol. 15 MILW, MKT, FRISCO, MP, KCS, DRGW (RPC) Passenger Cars Vol. 2 by Hal Carstens (Carstens). Plans & photos for #173-2, #173-3. Passenger Cars Vol. 3 by Hal Carstens (Carstens). Plans & photos for #173-7, #173-8. Milwaukee Road in Color Vols. 1-4 by several authors (Morning Sun) Milwaukee Road Color Guide to Freight & Passenger Equipment, Stauss (Morning Sun) Milwaukee Road Remembered by Jim Scribbins (Univ. -

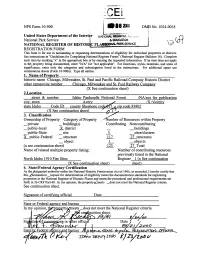

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-O018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ——— Page ——— SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 00001269 Date Listed: 10/26/00 Chicago. Milwaukee. St. Paul & Pacific Mineral MT Railroad Company Historic District Shoshone ID Property Name County State North Idaho 1910 Fire Sites Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. / Signature/of the Keeper Date of Action ^ =======^======================================================= Amended Items in Nomination: Location: The Montana location is: Mineral County - 061. Significance: Archeology (Historic/Non-Aboriginal) and Conservation are added as areas of significance. U. T. M. Coordinates: Point A is corrected to read: 603170 Previous Documentation: A 56-mile segment of the Milwaukee Road rail line from St. Regis to Avery was determined eligible for listing by the Keeper in 1995. (The current nomination represents a smaller segment of that larger linear district.) Photographs: Photograph #4 is omitted from the current nomination; as a result the remaining photographs are all misnumbered by one (1). The photographs were taken by Cort Sims, Panhandle NF and date from 1994; they reflect the current condition of the resources. These revisions were confirmed with the National Forest Service. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file NPS Form 10-900 VP • O dJUJ QMJB NO. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL REGISTER, t- National Park Service j & EDUCATION NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC_______ REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. -

National Register of Historic Places and Meets the Procedural and Professional Requirements Set Forth in 36 CRF Part 60

NPS Form 10-900 VP • O dJUJ QMJB NO. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL REGISTER, t- National Park Service j & EDUCATION NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC_______ REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in "Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms" (National Register Bulleten 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to thfc property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property______________________________________ historic name Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad Company Historic District other names/site number___Chicago. Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway Company (X See continuation sheet) 2.Location ___ ___ __ __ street & number Idaho Panhandle National Forest /NA/not for publication city, town Avery /X /vicinity state Idaho___Code ID county Shoshone codexflt/. A zip code 83802 ________(X See continuation sheet)___ 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property lumber of Resources within Property _ private _ building(s) Contributing Noncontributing _ public-local X district _ _buildings _ public-State _ site 5 _sites/clusters X public-Federal _ structure 117 27 structures _ object 1 _objects (x see continuation sheet) 123 27 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National North Idaho 1910 Fire Sites Register 1 (x See continuation (X See continuation sheet! ____sheet)___________ 4. -

The Hiawatha Story (Milwaukee Road) by Jim Scribbins

The Hiawatha Story (Milwaukee Road) By Jim Scribbins If searching for a book by Jim Scribbins The Hiawatha Story (Milwaukee Road) in pdf form, then you've come to right site. We presented the utter version of this ebook in PDF, ePub, DjVu, txt, doc forms. You may reading by Jim Scribbins online The Hiawatha Story (Milwaukee Road) either download. Additionally to this book, on our website you may read manuals and diverse art eBooks online, either downloading their as well. We like to draw regard what our site not store the book itself, but we give ref to website where you can download either read online. So if you have necessity to download pdf by Jim Scribbins The Hiawatha Story (Milwaukee Road) , then you've come to the right website. We have The Hiawatha Story (Milwaukee Road) txt, ePub, doc, PDF, DjVu formats. We will be pleased if you get back again and again. The story of the hiawatha by bilty, charles h.: milwaukee the story of the hiawatha bilty, charles h. Published by milwaukee road railfans, milwaukee, 1985. Condition: Near Fine Soft cover. View all copies of this book. Buy Used The Hiawatha Story - Wikipedia The Hiawatha Story is a 1970 non-fiction book on railroad history by Jim Scribbins, then an employee of the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (the Milwaukee Road Hiawatha - YouTube Oct 22, 2009 · Milwaukee Road: Superdome Olympian Hiawatha luxury passenger train 1952. - WDTVLIVE42 - Duration: 41:45. wdtvlive42 - Archive Footage 153,599 views The Morning Hiawatha - American-Rails.com The Morning Hiawatha was a new, ultra-fast streamliner the Milwaukee Road launched during early 1939 between Chicago and the Twin Cities. -

Steamtown NHS: Special History Study

Steamtown NHS: Special History Study Steamtown Special History Study STEAM OVER SCRANTON: THE LOCOMOTIVES OF STEAMTOWN SPECIAL HISTORY STUDY Steamtown National Historic Site, Pennsylvania Gordon Chappell National Park Service United States Department of the Interior 1991 Table of Contents stea/shs/shs.htm Last Updated: 14-Feb-2002 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/steamtown/shs.htm[8/16/2012 12:31:20 PM] Steamtown NHS: Special History Study Steamtown Special History Study TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION THE LOCOMOTIVES OF STEAMTOWN AMERICAN STEAM LOCOMOTIVES a. Baldwin Locomotive Works No. 26 b. Berlin Mills Railway No. 7 c. Boston and Maine Railroad No. 3713 d. Brooks-Scanlon Corporation No. 146 e. Bullard Company No. 2 f. Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad No. 565 g. E.J. Lavino and Company No. 3 h. Grand Trunk Western Railroad No. 6039 i. Illinois Central Railroad No. 790 j. Lowville and Beaver River Railroad No. 1923 k. Maine Central Railroad No. 519 l. Meadow River Lumber Company No. 1 m. New Haven Trap Rock Company No. 43 n. Nickel Plate Road (New York, Chicago and St. Louis) No.44 o. Nickel Plate Road (New York, Chicago and St. Louis) No. 759 p. Norwood and St. Lawrence Railroad No. 210 q. Public Service Electric and Gas Company No. 6816 r. Rahway Valley Railroad No. 15 s. Reading Company No. 2124 t. Union Pacific Railway No. 737 u. Union Pacific Railroad No. 4012 CANADIAN STEAM LOCOMOTIVES a. Canadian National Railways No. 47 b. Canadian National Railways No. 3254 c. Canadian National Railways No. 3377 d. -

LIBRARY Railroad Name Title 1 Author AA the Ann Arbor Railroad

LIBRARY Railroad_Name Title_1 Author AA The Ann Arbor Railroad Burkhardt, D. C. Jesse AC Stairway to the Stars, Colorado's Argentine Central Railway Abbott, Dan( #2397 of 3000) signed AC The Argentine Central Hollenback, Frank R. Atlantic Coast Line Railroads, Steam Locomotives, Ships and ACL History Prince, Richard E. ACL Atlantic Coast Line Passenger Service. The Postwar Years Goolsby, Larry ACL Atlantic Coast Line. The Standard Railroad of the South Griffin Jr., William E. ACL A History of The Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company Hoffman, Glenn ACL Atlantic Coast Line. The Diesel years Warren L Calloway Tracks of the Black Bear - The Story of The Algoma Central ACR Railroad Wilson, Dale ALCO Classic Locomotives - Alco Switchers Szachacz, Keith ALCO ALCO FA-2. Diesel Data Series Book 2 Peck, David ALCO ALCO Offical Color Photography Appel, Walter A. ALCO ALCO Century 430 - 4 Motor 3000 HP Spec n/a ALCO ALCO Century 630 - 6 Motor 3000 HP Spec n/a ALCO ALCO Hydraulic 643 - H,4300 GHP Diesel n/a ALCO An Acquaintance With ALCO Olmsted, Robert P. Alco Trackside with Mr Alco George W Hockaday Jim Odell and Len Kilian ALCO's FA running in the shadow an in - depth look at the Alco _ Alco GE/ MLW FA series R Craig Rutherford ALCO's Northeast - Beyond Schenectady, smoke , guts and glory Alco 1969 - 2006 Mike Confalone and Joe Posik ALG Algoma Central Railway Nock, OS AMTRAK Amtrak At Milepost 10 Zimmermann, Karl AMTRAK Amtrak Annual Report-1979 NA AMTRAK Amtrak Heritage-Passenger Trains in the East 1971-1977 Taibi, John AMTRAK Amtrak Consists (As of December 1976) Wayner, Robert J. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY Books, 1997)

Ghost Towns of the Montana Prairie (Boulder, Colorado: Fred Pruett BIBLIOGRAPHY Books, 1997). Books Ball, Don Jr., Portrait of the Rails (New York: Galahad Books, 1972). Adler, Cyrus, Jacob H. Schiff: His Life and Letters (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran and Co. Inc, 1928). Bateman, Bob, Big Blackfoot Railway (Deer Lodge, MT: Platen Press, 1980). Allen, G. Freeman, The Fastest Trains in the World (New York: Charles Berle, Adolph, and Means, Gardiner, The Modern Corporation and Private Scribner & Sons, 1978). Property (New York: Commerce Clearing House Publishing Co., 1932). Akin, Edward N., Flagler: Rockefeller Partner & Florida Baron (Kent, Ohio: Berton, Pierre, The Impossible Railway (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972). Kent State University Pres, 1988). Bilty, Charles H., The Story of the Hiawatha (Milwaukee: Ken Cook, Co., 1985). American Institute of Mining Engineers, Transactions: Montana Volume (New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers, 1914). Brain, Insley J. Jr., The Milwaukee Road Electrification (San Mateo, CA: Bay Area Electric Assoc. and the Western Railroader, 1961). Athearn, Robert G., "Railroad to a Far-off Country -- the Utah & Northern," Montana's Past, Selected Essays, Richard Roeder and Michael Malone, Brooks, John, Once in Golconda: a True Drama of Wall Street, 1920-1938 (New editors (Missoula, Montana: University of Montana Press, 1973). York: Harper & Row, 1969). Abbot, Newton Carl, Montana in the Making (Billings, Montana: Gazette Brown, Dee, Hear That Lonesome Whistle Blow (New York: Touchstone Books, Printing Co., 1964). 1977). American Association of Railroad Superintendents, Proceedings of the Burlingame, Merrill G., The Montana Frontier (Helena, Montana: The Seventieth Annual Meeting (Topeka, Kansas: Hall Lithographing Co., Montana Historical Society, 1942). -

The Milwaukee Road Pacific Extension: the Myth of Superiority

The Milwaukee Road Pacific Extension: The myth of superiority Winston Churchill said, “History is written by the victors.” There’s a lot of truth to that. But it’s also true that sometimes leads to the whole story not being told. On the other hand, the Internet wasn’t around in Churchill’s day, but today one can read alternate histories and theories of history on just about any subject. Such is the case with the Milwaukee Road’s Pacific Extension. Most who are even vaguely familiar with American railroading know of the Milwaukee Road being the only American “transcontinental” line to have been mostly abandoned. Several sites online claim to explain why this happened. As you read these, you will likely detect a common theme: A railroad that had everything going for it, with superior operating characteristics. As an example, an online source “A brief review of the failure of the Milwaukee Road” probably says it best in its opening statement, “The Milwaukee Road was well built, with the shortest and lowest-cost route to the Pacific Northwest. It was innovative, pioneering not only in electrification, but also things like roller-bearings (greatly reducing rolling resistance), refrigerator cars, and high-speed passenger trains. Later it lead in hauling cargo containers, with three-quarters of the traffic from the Port of Seattle, and even as late as 1969 it opened the largest facility in the region for transshipping automobiles. Yet, it failed.” The reasons for the “why” of the failure of the Pacific Extension run the full gamut from conspiracy to deferred maintenance to poor management. -

June 2010 Newsclr3

11 Volume 41 Number 6 June 2010 Jackson St Roundhouse is Now the June Meeting Location Directions Page 2 Riding Auto Train Then and Now By Russ Isbrandt Top: Southbound Auto Train at Jacksonville, March 6, 1976. Bottom: April 2, 2010 northbound Amtrak Auto Train at almost the same location. Note weed overgrown track under the next car. Photos by Russ Isbrandt Contents Meeting Notice Officer Contact Directory P.2 The June meeting of the Northstar Chapter of the NRHS will be held at a NEW LOCATION, the Directions to Jackson St. Roundhouse P.2 Jackson Street Roundhouse, 193 Pennsylvania Ave. East, St. Paul, June 19th at 7pm CDT. See Auto Train Then and Now P.2 map on following page. Trains Newswire P.6 There will be a pre-meeting get-together at the Keys Cafe and Bakery downtown at 500 N. Rob- Railway Age Breaking News P.6 ert St. starting about 5:15 pm. Call Bob Clark- son at 651-636-2323 and leave a message with Chicago Metra Boss Commits Suicide P.7 your name and the number of persons coming with you. Chapter Participates in National Train Day P.7 Program: H. Martin Swan will present a DVD of Meeting Minutes from May 15th Meeting P.7 some of his 8 mm movies of passenger trains in the Seattle area in the ‘60s and a trip to Chur- Upcoming Chapter Events P.8 chill, Manitoba on VIA Rail. 1 Northstar Chapter Officers Board of Directors Office Name Email Phone President Cy Svobodny [email protected] 651-455-0052 Vice President Dawn Holmberg [email protected] 763-784-8835 Past President Mark Braun [email protected] 320-587-2279 National Director Bill Dredge [email protected] 952-937-1313 Treasurer Dan Meyer [email protected] 763-784-8835 Secretary Dave Norman [email protected] 612-729-2428 Trustee Bob Clarkson [email protected] 651-636-2323 Staff Program Chairman John Goodman [email protected] Newsletter Editor Russ Isbrandt [email protected] 651-426-1156 Webmaster Dan Meyer Website: www.northstar-nrhs.org Chapter Mail Box Northstar Chapter PO Box 120832 St.