Issue 9 May 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fields Corporation Digital Annual Report 2017

FIELDS CORPORATION Annual Report 2017 April 1, 2016 – March 31, 2017 DIGITAL ANNUAL REPORT 2017 FIELDS CORPORATION CONTENTS Management Message The Greatest Leisure for All People 02 CEO Message 01 04 COO Message Review of Business Activities Toward the enhancing IP value and improving profitability 07 Consolidated Financial Highlights 06 08 Business Results Review 10 Business Overview 15 Market Data Financial Section Consolidated Financial Statement 19 Consolidated Financial Statement 18 47 Independent Auditor’s Report CSR / Corporate Governance / Company and Stock Information For the contributing to happiness of society 49 FIELDS’ CSR 48 50 Corporate Governance 52 About FIELDS (Company Information) 55 FIELDS’ Advances 61 Stock Information Management Message The Greatest Leisure for All People FIELDS CORPORATION aim to become a company able to continuously create the greatest leisure for all people throughout the world. CONTENTS CEO Message Chairman and CEO Hidetoshi Yamamoto 02 COO Message President and COO Tetsuya Shigematsu 04 FIELDS CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2017 01 Management Message >CEO Message MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN and CEO CEO Message Greetings I would like to express my sincere appreciation for concerning the Company’s results in the last fiscal year. the understanding and continued support of our We will not waste this experience, instead, we will use shareholders, investors and all our other it to spur ourselves on to ensure vitality in the future, stakeholders. and our management and employees will strive Moreover, I would like to convey our deepest diligently in unison. apologies for any distress caused to our stakeholders The Company’s Establishment and Innovation of PS Distribution Since the foundation of FIELDS, we have become of pachinko and pachislot machines installed in integrated in the lives of many people in every region pachinko halls, the services offered, through to the across Japan, discovering unrealized potential for very format of the pachinko hall space itself. -

The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: from Inception To

THE PORTUGUESE EXPEDITIONARY CORPS IN WORLD WAR I: FROM INCEPTION TO COMBAT DESTRUCTION, 1914-1918 Jesse Pyles, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Robert Citino, Committee Member Walter Roberts, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Pyles, Jesse, The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: From Inception to Destruction, 1914-1918. Master of Arts (History), May 2012, 130 pp., references, 86. The Portuguese Expeditionary Force fought in the trenches of northern France from April 1917 to April 1918. On 9 April 1918 the sledgehammer blow of Operation Georgette fell upon the exhausted Portuguese troops. British accounts of the Portuguese Corps’ participation in combat on the Western Front are terse. Many are dismissive. In fact, Portuguese units experienced heavy combat and successfully held their ground against all attacks. Regarding Georgette, the standard British narrative holds that most of the Portuguese soldiers threw their weapons aside and ran. The account is incontrovertibly false. Most of the Portuguese combat troops held their ground against the German assault. This thesis details the history of the Portuguese Expeditionary Force. Copyright 2012 by Jesse Pyles ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The love of my life, my wife Izabella, encouraged me to pursue graduate education in history. This thesis would not have been possible without her support. Professor Geoffrey Wawro directed my thesis. He provided helpful feedback regarding content and structure. Professor Robert Citino offered equal measures of instruction and encouragement. -

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014 - August 2016 *To search for items, please press Ctrl + F and enter the title in the search box at the top right hand corner or at the bottom of the screen. LEGEND : BK - Book; AL - Adult Library; YPL - Children Library; AV - Audiobooks; FIC - Fiction; ANF - Adult Non-Fiction; Bio - Biography/Autobiography; ER - Early Reader; CFIC - Picture Books; CC - Chapter Books; TOD - Toddlers; COO - Cookbook; JFIC - Junior Fiction; JNF - Junior Non Fiction; POE -Children's Poetry; TRA - Travel Guide Type Location Collection Call No Title AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GIL Big magic : Creative living / Elizabeth Gilbert. AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GRA Originals : How non-conformists move the world / Adam Grant. Irrationally yours : On missing socks, pick up lines, and other existential puzzles / Dan AV AL ANF CD 153.4 ARI Ariely. Think like a freak : The authors of Freakonomics offer to retrain your brain /Steven D. AV AL ANF CD 153.43 LEV Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner. AV AL ANF CD 153.8 DWE Mindset : The new psychology of success / Carol S. Dweck. The geography of genius : A search for the world's most creative places, from Ancient AV AL ANF CD 153.98 WEI Athens to Silicon Valley / Eric Weiner. AV AL ANF CD 158 BRO Rising strong / Brene Brown. AV AL ANF CD 158 DUH Smarter faster better : The secrets of prodctivity in life and business / Charles Duhigg. AV AL ANF CD 158.1 URY Getting to yes with yourself and other worthy opponents / William Ury. 10% happier : How I tamed the voice in my head, reduced stress without losing my edge, AV AL ANF CD 158.12 HAR and found self-help that actually works - a true story / Dan Harris. -

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a doctoral degree in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Nicholas Milne-Walasek, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT In a cultural context, the First World War has come to occupy an unusual existential point half- way between history and art. Modris Eksteins has described it as being “more a matter of art than of history;” Samuel Hynes calls it “a gap in history;” Paul Fussell has exclaimed “Oh what a literary war!” and placed it outside of the bounds of conventional history. The primary artistic mode through which the war continues to be encountered and remembered is that of literature—and yet the war is also a fact of history, an event, a happening. Because of this complex and often confounding mixture of history and literature, the joint roles of historiography and literary scholarship in understanding both the war and the literature it occasioned demand to be acknowledged. Novels, poems, and memoirs may be understood as engagements with and accounts of history as much as they may be understood as literary artifacts; the war and its culture have in turn generated an idiosyncratic poetics. It has conventionally been argued that the dawn of the war's modern literary scholarship and historiography can be traced back to the late 1960s and early 1970s—a period which the cultural historian Jay Winter has described as the “Vietnam Generation” of scholarship. -

Remembrance Ni

!1 remembrance ni Unique memorial to 36th Ulster Division In Belfast Cathedral there is a unique war memorial to the 36th (Ulster) Division. It is a lectern which was presented by the Division O"cers’ Old Comrades’ Association. The war memorial lectern was dedicated on 10/11/1929, the same remembrance ni Issue 19 !2 weekend as the opening of the Cenotaph in the City Hall’s Garden of Remembrance. # The Cathedral was packed. The Queen’s Island Band, under George Dean, late of the, Norfolk Regiment, took part in the Service. The Dedication was performed by Bishop Grierson at the request of Col H A Packenham, CMG, on behalf of the donors. # The lectern contains Ireland’s Memorial Records, 1914-1918, in eight volumes which record the names of more than 49,000 Irishmen. The Records and the bronze statuette which surmounts the lectern were the gift of the Irish National War Memorial Committee. # The statuette is the work of Morris Harding and was designed by the architect of the Cathedral Sir Charles Nicholson, and for whom Maurice Harding had carried out many of the sculptured elements in the building. A contemporary Belfast Telegraph photograph of the lectern shows it covered in poppies. # In his sermon Revd A A Luce, MC, DD, who had served as a Captain, 12 Batt, RIR, pointed out that abstainers in the Ulster Division stuck to their principles, even refusing their rum ration in the front-line trenches! # remembrance ni Issue 19 !3 Arthur Aston Luce. MC, (1882 - 1977) was professor of philosophy at Trinity College, Dublin and also Precentor of St. -

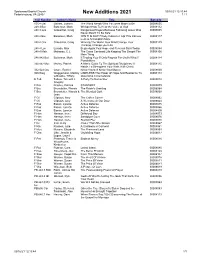

New Additions 2021 1 / 1

Spotswood Baptist Church 03/16/21 12:10:44 Federicksburg, VA 22407 New Additions 2021 1 / 1 Call Number Author's Name Title Barcode 155.4 Gai Gaines, Joanna The World Needs Who You were Made to Be 00008055 248.3 Bat Batterson, Mark Whisper:How To Hear the Voice of God 00008112 248.3 Gro Groeschel, Craig Dangerous Prayers:Because Following Jesus Was 00008095 Never Meant To Be Safe 248.4 Bat Batterson, Mark WIN THE DAY:7 Daily Habits to Help YOu bStress 00008117 Less & Accomplish More 248.4 Gro Groeschel, Craig Winning The WarIn Your Mind:Change Your 00008129 Thinking, Change your Life 248.4 Luc Lucado, Max Begin Again:Your Hope and Renewal Start Today 00008054 248.4 Mah Mahaney, C.J. The Cross Centered Life:Keeping The Gospel The 00008106 Main Thing 248.842 Bat Batterson, Mark If:Trading Your If Only Regrets For God's What If 00008114 Possibilities 248.842 Mor Morley, Patrick A Man's Guide To The Spiritual Disciplines:12 00008115 Habits To Strengthen Your Walk With Christ 332.024 Cru Cruze, Rachel Know Yourself Know Your Money 00008060 920 Weg Weggemann, Mallory LIMITLESS:The Power Of Hope And Resilience To 00008118 w/Brooks, Tiffany Overcome Circumstance E Teb Tebow, Tim w/A.J. A Party To Remember 00008018 Gregory F Bra Bradley, Patricia STANDOFF 00008079 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda The Robin's Greeting 00008084 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda & The Blended Quilt 00008068 Jean F Cli Clipston, Amy The Coffee Corner 00008062 F Cli Clipston, Amy A Welcome At Our Door 00008064 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active Defense 00008015 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active -

VOL. Iurtliant D J O I M L G D E Mocrat M.Isox, MICIIW.In. Siij/Inainiaii

MASON, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 21,1880. NO. 43 VOL. V. Trophy. I.OCAI.. AND GGlVEnAL. NEliVS. DEMOCRATIC MEKTIMSS. Your Folks nnd Our Folk.s. This Hnmbleloninn Sinllion will make a Iurtliant djoimlg Democrat >Vniito.d. HON. H. P. HKNDERSON, Henry McNeil, now nf Lainsbiirg, wns in fall season at our stables in Mason, from Oct. 1st to Dec. Ihth, nt the low price of Published every Thursday Onions, Potatoes, and Hoans, wanted nl Maaon'.s own candidate for Attorney Gen the city calling on friends Sunday. hy lflQ.OO for the season, with the privilege once. flu.s'T & Ellis. eral, on the Democratic Stato ticket, hns Homer Cornell and wife of fjanaing, wore nf returning free of charge in ISSl tdl that M. 1». WII ITMOnE, consented lo address tho eiti'/.cna of Mason, in tho city calling on friends 'i'uosday. , do not prove in foal. All who intend using M.iSOX, MICIIW.iN. Circulation thia weak, 1,568. upon the political isaucs of the day, nt the this fashionable bred trotting sire should A. L. '.Vanderconk has been ([uite sick do HO, as he will never stand for as low n court house nn Monday evening, Nov. 1st,' Bay City had a l> 10,000 fire Monday but is again nblo to attend to business. price,ai;ain. Respectfully yours, One Yonr, $1.50 ; Sin montha, 7S oenia ; Three tho last evening boforo the eventful 2d of L. C. •Weiir, nife'ht. Dr. Daniel Campbell of Rclmont, Cana monlhi, 40 csnla. November. He is entitled to a full houae. -

Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22

T HE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A TLANTIC SLAVERY AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD I BRAHIMA THIAW AND DEBORAH L. MACK, GUEST EDITORS A tlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Experiences, Representations, and Legacies An Introduction to Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy V The Slavery Business and the Making of “Race” in Britain OLUME 61 and the Caribbean Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME SUPPLEMENT 61 22 From Country Marks to DNA Markers: The Genomic Turn S UPPLEMENT 22 in the Reconstruction of African Identities Diasporic Citizenship under Debate: Law, Body, and Soul Slavery, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Racialization of Africans Sovereignty after Slavery: Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti O CTOBER 2020 From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The “Changing Same” of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants Serving Status on the Gambia River Before and After Abolition The Problem: Religion within the World of Slaves The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons A “tone of voice peculiar to New-England”: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy Raising -

Download Download

British Journal for Military History Volume 7, Issue 1, March 2021 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike ISSN: 2057-0422 Date of Publication: 19 March 2021 Citation: Roslyn Shepherd King Pike, ‘What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918’, British Journal for Military History, 7.1 (2021), pp. 87-112. www.bjmh.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The BJMH is produced with the support of IDENTIFYING MILITARY ENGAGEMENTS IN EGYPT & THE LEVANT 1915-1918 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915- 1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike* Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article examines the official names listed in the 'Egypt and Palestine' section of the 1922 report by the British Army’s Battles Nomenclature Committee and compares them with descriptions of military engagements in the Official History to establish if they clearly identify the events. The Committee’s application of their own definitions and guidelines during the process of naming these conflicts is evaluated together with examples of more recent usages in selected secondary sources. The articles concludes that the Committee’s failure to accurately identify the events of this campaign have had a negative impacted on subsequent historiography. Introduction While the perennial rose would still smell the same if called a lily, any discussion of military engagements relies on accurate and generally agreed on enduring names, so historians, veterans, and the wider community, can talk with some degree of confidence about particular events, and they can be meaningfully written into history. -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

Year 10 : in the News

Year 10 : In the News Graphic Design Examples of poster designs • Art work that is produced to COMMUNICATE or EXPLAIN an idea, to a group of people. • Graphic designers combine words, symbols and images to create a visual representation of ideas and messages. Propaganda Posters • Today, propaganda is commonly thought of to be false or misleading and the term is commonly used in a derogatory way. However, during WW1 & WW2 these posters were created to spreading ideas or information to further a cause. Keep Calm and Carry On origins • A motivational poster produced by the British government in 1939 in preparation for World War II. The poster was intended to raise the morale of the British public, threatened with air attacks on major cities. Although 2.45 million copies were printed, and although the Blitz did in fact take place, the poster was only rarely publicly displayed and was little known until a copy was rediscovered in 2000 ‘In the News’ Design Brief • Many artists, designers and art movements create artwork inspired by current and relevant topics in the news. Propaganda posters from the World War were used to encourage the public to conform. Russian constructivism came after WW1 to provide structure and like the London Underground Posters to educate the public and finally Banksy and Shepard Fairy design posters and art work to raise awareness of political views. • Investigate appropriate resources and design a poster or piece of artwork that communicates a relevant topic that is in the news. Year 10 : In the News Starting Point We Can Do It! It’s Our Flag We Can Do It!" is an American World War II It's Our Flag Fight for it Work for it. -

Egyptian Labor Corps: Logistical Laborers in World War I and the 1919 Egyptian Revolution

EGYPTIAN LABOR CORPS: LOGISTICAL LABORERS IN WORLD WAR I AND THE 1919 EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Kyle J. Anderson August 2017 © 2017 i EGYPTIAN LABOR CORPS: LOGISTICAL LABORERS IN WORLD WAR I AND THE 1919 EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION Kyle J. Anderson, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 This is a history of World War I in Egypt. But it does not offer a military history focused on generals and officers as they strategized in grand halls or commanded their troops in battle. Rather, this dissertation follows the Egyptian workers and peasants who provided the labor that built and maintained the vast logistical network behind the front lines of the British war machine. These migrant laborers were organized into a new institution that redefined the relationship between state and society in colonial Egypt from the beginning of World War I until the end of the 1919 Egyptian Revolution: the “Egyptian Labor Corps” (ELC). I focus on these laborers, not only to document their experiences, but also to investigate the ways in which workers and peasants in Egypt were entangled with the broader global political economy. The ELC linked Egyptian workers and peasants into the global political economy by turning them into an important source of logistical laborers for the British Empire during World War I. The changes inherent in this transformation were imposed on the Egyptian countryside, but workers and peasants also played an important role in the process by creating new political imaginaries, influencing state policy, and fashioning new and increasingly violent repertoires of contentious politics to engage with the ELC.