Remembrance Ni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St.Helens Armed Forces Covenant Report 2019

St.Helens Armed Forces Covenant Progress Report Report 11 St.Helens Armed Forces Community Covenant Progress Report 11 2018-19 St.Helens Armed Forces Covenant Progress Report 2019 Foreword After such a productive and event filled year I am once more reminded in viewing the information within this Armed Forces Covenant Report of the great honour it is to support the Armed Forces Community as St.Helens Armed Forces Ambassador. The diversity of the British Armed Forces Community never ceases to amaze me. It stretches beyond the differences between Her Majesty’s Naval Service, The British Army, and The Royal Air Force, it is more diverse that the different traditions and customs of Battalion, Regiment and Unit; the diversity of the Armed Forces Community reflects the diversity of society as a whole. In attempting to ensure we provide the Armed Forces Community with equality of access to Public Services, the Council and its Partners must keep this diversity in mind. In the modern Armed Forces there is a clear representation of both genders in all Services and Rank. The Community spans all generations from the youngest Cadet to the oldest Veteran. It incorporates the different ethnicities and cultures of the Commonwealth, as well as reflecting the varied identities of the Shires, Boroughs, and Regions that make up the Nations of the United Kingdom. In the past 5 years we have celebrated the Borough’s First World War Victoria Cross recipient, and they too reflect this diversity. One served with the local South Lancashire Regiment, a second with the London based Royal Fusiliers, a third with the Irish Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, and a fourth with the Canadian Royal Winnipeg Rifles. -

The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: from Inception To

THE PORTUGUESE EXPEDITIONARY CORPS IN WORLD WAR I: FROM INCEPTION TO COMBAT DESTRUCTION, 1914-1918 Jesse Pyles, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Robert Citino, Committee Member Walter Roberts, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Pyles, Jesse, The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: From Inception to Destruction, 1914-1918. Master of Arts (History), May 2012, 130 pp., references, 86. The Portuguese Expeditionary Force fought in the trenches of northern France from April 1917 to April 1918. On 9 April 1918 the sledgehammer blow of Operation Georgette fell upon the exhausted Portuguese troops. British accounts of the Portuguese Corps’ participation in combat on the Western Front are terse. Many are dismissive. In fact, Portuguese units experienced heavy combat and successfully held their ground against all attacks. Regarding Georgette, the standard British narrative holds that most of the Portuguese soldiers threw their weapons aside and ran. The account is incontrovertibly false. Most of the Portuguese combat troops held their ground against the German assault. This thesis details the history of the Portuguese Expeditionary Force. Copyright 2012 by Jesse Pyles ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The love of my life, my wife Izabella, encouraged me to pursue graduate education in history. This thesis would not have been possible without her support. Professor Geoffrey Wawro directed my thesis. He provided helpful feedback regarding content and structure. Professor Robert Citino offered equal measures of instruction and encouragement. -

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a doctoral degree in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Nicholas Milne-Walasek, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT In a cultural context, the First World War has come to occupy an unusual existential point half- way between history and art. Modris Eksteins has described it as being “more a matter of art than of history;” Samuel Hynes calls it “a gap in history;” Paul Fussell has exclaimed “Oh what a literary war!” and placed it outside of the bounds of conventional history. The primary artistic mode through which the war continues to be encountered and remembered is that of literature—and yet the war is also a fact of history, an event, a happening. Because of this complex and often confounding mixture of history and literature, the joint roles of historiography and literary scholarship in understanding both the war and the literature it occasioned demand to be acknowledged. Novels, poems, and memoirs may be understood as engagements with and accounts of history as much as they may be understood as literary artifacts; the war and its culture have in turn generated an idiosyncratic poetics. It has conventionally been argued that the dawn of the war's modern literary scholarship and historiography can be traced back to the late 1960s and early 1970s—a period which the cultural historian Jay Winter has described as the “Vietnam Generation” of scholarship. -

The Great War, 1914-18 Biographies of the Fallen

IRISH CRICKET AND THE GREAT WAR, 1914-18 BIOGRAPHIES OF THE FALLEN BY PAT BRACKEN IN ASSOCIATION WITH 7 NOVEMBER 2018 Irish Cricket and the Great War 1914-1918 Biographies of The Fallen The Great War had a great impact on the cricket community of Ireland. From the early days of the war until almost a year to the day after Armistice Day, there were fatalities, all of whom had some cricket heritage, either in their youth or just prior to the outbreak of the war. Based on a review of the contemporary press, Great War histories, war memorials, cricket books, journals and websites there were 289 men who died during or shortly after the war or as a result of injuries received, and one, Frank Browning who died during the 1916 Easter Rising, though he was heavily involved in organising the Sporting Pals in Dublin. These men came from all walks of life, from communities all over Ireland, England, Scotland, Wales, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, India and Sri Lanka. For all but four of the fifty-two months which the war lasted, from August 1914 to November 1918, one or more men died who had a cricket connection in Ireland or abroad. The worst day in terms of losses from a cricketing perspective was the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916, when eighteen men lost their lives. It is no coincidence to find that the next day which suffered the most losses, 9 September 1916, at the start of the Battle of Ginchy when six men died. -

Download Download

British Journal for Military History Volume 7, Issue 1, March 2021 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike ISSN: 2057-0422 Date of Publication: 19 March 2021 Citation: Roslyn Shepherd King Pike, ‘What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918’, British Journal for Military History, 7.1 (2021), pp. 87-112. www.bjmh.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The BJMH is produced with the support of IDENTIFYING MILITARY ENGAGEMENTS IN EGYPT & THE LEVANT 1915-1918 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915- 1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike* Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article examines the official names listed in the 'Egypt and Palestine' section of the 1922 report by the British Army’s Battles Nomenclature Committee and compares them with descriptions of military engagements in the Official History to establish if they clearly identify the events. The Committee’s application of their own definitions and guidelines during the process of naming these conflicts is evaluated together with examples of more recent usages in selected secondary sources. The articles concludes that the Committee’s failure to accurately identify the events of this campaign have had a negative impacted on subsequent historiography. Introduction While the perennial rose would still smell the same if called a lily, any discussion of military engagements relies on accurate and generally agreed on enduring names, so historians, veterans, and the wider community, can talk with some degree of confidence about particular events, and they can be meaningfully written into history. -

Comber Historical Society

The Story Of COMBER by Norman Nevin Written in about 1984 This edition printed 2008 0 P 1/3 INDEX P 3 FOREWORD P 4 THE STORY OF COMBER - WHENCE CAME THE NAME Rivers, Mills, Dams. P 5 IN THE BEGINNING Formation of the land, The Ice Age and after. P 6 THE FIRST PEOPLE Evidence of Nomadic people, Flint Axe Heads, etc. / Mid Stone Age. P 7 THE NEOLITHIC AGE (New Stone Age) The first farmers, Megalithic Tombs, (see P79 photo of Bronze Age Axes) P 8 THE BRONZE AGE Pottery and Bronze finds. (See P79 photo of Bronze axes) P 9 THE IRON AGE AND THE CELTS Scrabo Hill-Fort P 10 THE COMING OF CHRISTIANITY TO COMBER Monastery built on “Plain of Elom” - connection with R.C. Church. P 11 THE IRISH MONASTERY The story of St. Columbanus and the workings of a monastery. P 12 THE AUGUSTINIAN MONASTERY - THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY, THE NORMAN ENGLISH, JOHN de COURCY 1177 AD COMBER ABBEY BUILT P13/14 THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY IN COMBER The site / The use of river water/ The layout / The decay and plundering/ Burnt by O’Neill. P 15/17 THE COMING OF THE SCOTS Hamiltons and Montgomerys and Con O’Neill-The Hamiltons, 1606-1679 P18 / 19 THE EARL OF CLANBRASSIL THE END OF THE HAMILTONS P20/21 SIR HUGH MONTGOMERY THE MONTGOMERIES - The building of church in Comber Square, The building of “New Comber”. The layout of Comber starts, Cornmill. Mount Alexander Castle built, P22 THE TROUBLES OF THE SIXTEEN...FORTIES Presbyterian Minister appointed to Comber 1645 - Cromwell in Ireland. -

49Er1950no050

-L'MBER SO 1850 nary, 1950 THE FORTY-NINER Important Services OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS A new arm of the Government, the Department of Economic Affairs, was established at the regular session of the Legislature in 1945. Functions of the Department, according: to the authorizing Act, were to "further and encourage orderly, economic, cultural and social de- velopment for the betterment of the people of the Province in accord- ance with the principles and requirements of a democracy, and to assist in and advance the proper rehabilitation of men and women returning to the Province from the Armed Services of Canada and from war industries. @ Cultural Activities Branch to stimu- @ Agent General in London whose par- late interest in the fine arts in par- ticular concern is immigration and ticular and recreation generally. makes final selection of applicants for immigration to the Province. @ Industrial Development and Economic Research Branch for the purpose of solving technical problems relating to @ Film and Photographic Branch @ industries coming to Alberta, etc. Supplying pictorial matter to illus- trate newspaper and magazine arti- @ Public Relations Office to establish cles publicizing Alberta. and maintain good will between the public and various departments of the @ Southern Alberta Branch @ Situated Government. in Calgary. Handling all business of @ Publicity Bureau handling advertis- the department and its branches in ing, news and features publicizing Southern Alberta. Alberta. @ Alberta Travel Bureau promoting in- @ Iimmigr.ation Branch to look after the terest in Alberta's Tourist attractions screening of applicants, welfare of in the local, national and internation- immigrants, etc. al fields. -

Saskatchewan Virtual War Memorial in Memory of Second Lieutenant Edmund De Wind VC Who Died on 21 Mar 1918

Saskatchewan Virtual War Memorial In memory of Second Lieutenant Edmund De Wind VC who died on 21 Mar 1918 Service details Conflict WWI Service British Army Unit Royal Irish Rifles Rank Second Lieutenant Service number 79152 Date of death 19180321 Cause of death killed in action Decorations Victoria Cross Narrative history Second Lieutenant (Royal Irish Rifles, British Army) Edmund De Wind VC (b.1883) was KIA 19180321 and is commemorated on the Pozières Memorial, France, for over 14,000 casualties of the United Kingdom and South African forces who have no known grave and who fell in France during the Fifth Army area retreat on the Somme from 21 March to 7 August 1918. He was the son of Arthur Hughes and Margaret De Wind of Comber, Down, Ireland, and worked at the Canadian Bank of Commerce at Yorkton and Humboldt before the war. He enlisted as a private (79152) in the 31st Battalion at Edmonton in late 1914 and was commissioned in the Imperial Army six months before his death. From De Wind's Victoria Cross citation: For most conspicuous bravery and self-sacrifice on the 21st March, 1918, at the Race Course Redoubt, near Grugies. For seven hours he held this most important post, and though twice wounded and practically single-handed, he maintained his position until another section could be got to his help. On two occasions, with two N.C.O.'s only, he got out on top under heavy machine gun and rifle fire, and cleared the enemy out of the trench, killing many. He continued to repel attack after attack until he was mortally wounded and collapsed. -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

Scole War Memoria

SCOLE TM 15019 78931 WW1 - 13 + 1* WW2 - 7 + 1* With acknowledgement to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission http://www.cwgc.org/ WW1 Casualties Awards Rank Number Service Unit Age Parish Conflict Date Notes Australian Infantry, Son of Michael and Marian Beverley, of Scole, Norfolk, Michael BEVERLEY Military Medal Private 5338 9th Bn. 44 Scole WW1 27/03/1918 A.I.F. England. Born at Norwich Son of John and Eliza Bryant, of Lodge Cottage, Arthur John BRYANT Private 40007 Norfolk Regt. 9th Bn. 22 Scole WW1 15/09/1916 Winfarthing Samuel BRYANT Private 40006 Norfolk Regt. 9th Bn. 21 Scole WW1 08/10/1918 Born in Burgate Frank BURRELL Corporal 22484 Norfolk Regt. 8th Bn. 25 Scole WW1 18/08/1917 Son of Emma Burrell, of The Gothic, Scole Frederick Northumberland 1st/4th Born 1898 in Canning Town, London. Resident of Scole in DEAN Private 204064 19 Scole WW1 25/10/1917 Charles Fusiliers Bn. 1911 census, enlisted in Norwich Cecil GARDINER* Private 33141 Essex Regt. 11th Bn. 22 Scole WW1 27/05/1918 Son of Alfred and Ellen Gardiner, of Scole. Lance Jesse GARDINER 354400 London Regt. 7th Bn. 25 Scole WW1 09/02/1917 Son of Alfred and Ellen Gardiner, of Scole Corporal G.W. GARDINER Scole WW1 not found Not named on the Norfolk Roll of Honour for Scole John Thomas HOOLHOUSE Private 23072 Border Regt. 7th Bn. - Scole WW1 08/08/1916 Formerly (19032) Norfolk Regt. Arthur LEEDER Private 3/10388 Norfolk Regt. 7th Bn. - Scole WW1 01/12/1917 Born in Thelveton. (also named at Thelveton) Machine Gun Corps Henry Arthur LEGGETT Private 85713 14th Bn. -

Smythe-Wood Series B

Mainly Ulster families – “B” series – Smythe-Wood Newspaper Index Irish Genealogical Research Society Dr P Smythe-Wood’s Irish Newspaper Index Selected families, mainly from Ulster ‘SERIES B’ The late Dr Patrick Smythe-Wood presented a large collection of card indexes to the IGRS Library, reflecting his various interests, - the Irish in Canada, Ulster families, various professions etc. These include abstracts from various Irish Newspapers, including the Belfast Newsletter, which are printed below. Abstracts are included for all papers up to 1864, but excluding any entries in the Belfast Newsletter prior to 1801, as they are fully available online. Dr Smythe-Wood often found entries in several newspapers for the one event, & these will be shown as one entry below. Entries dealing with RIC Officers, Customs & Excise Officers, Coastguards, Prison Officers, & Irish families in Canada will be dealt with in separate files. In most cases, Dr Smythe-Wood has recorded the exact entry, but in some, marked thus *, the entries were adjusted into a database, so should be treated with more caution. There are further large card indexes of Miscellaneous notes on families which are not at present being digitised, but which often deal with the same families treated below. ACR: Acadian Recorder LON The London Magazine ANC: Anglo-Celt LSL Londonderry Sentinel ARG Armagh Guardian LST Londonderry Standard BAA Ballina Advertiser LUR Lurgan Times BAI Ballina Impartial MAC Mayo Constitution BAU Banner of Ulster NAT The Nation BCC Belfast Commercial Chronicle NCT -

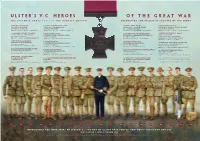

Ulster's V.C. Heroes of the Great

ULSTER’S V.C. HEROES OF THE GREAT WAR The Victoria Cross (V.C.) is the highest British decoration for valour in the face of the enemY 1. Sergeant David Nelson 6. Second Lieutenant Hugh Colvin 11. Private Thomas Hughes 16. Private James Crichton ‘L’ Battery Royal Artillery 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers 2nd Battalion Auckland Infantry Regiment Born in Stranooden, County Monaghan Born in Burnley, of Ulster parentage Born in Castleblayney, County Monaghan Born in Carrickfergus, County Antrim Awarded the V.C. for actions at Néry, France 1st September 1914 Awarded the V.C. for actions near Ypres, Belgium 20th September 1917 Awarded the V.C. for actions at Guillemont, France 3rd September 1916 Awarded the V.C. for actions near Crèvecœur, France 30th September 1918 2. Major Ernest Wright Alexander 7. Sergeant James Somers 12. Sergeant- Major Robert Hill Hanna 17. Lieutenant Geoffrey St. George 119th Battery Royal Field Artillery 1st Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers 29th Battalion Canadian Expeditionary Force Shillington Cather Born in Liverpool, to a Belfast mother Born in Belturbet, County Cavan Born in Kilkeel, County Down 9th Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers Awarded the V.C. for actions at Elouges, Belgium 24th August 1914 Awarded the V.C. for actions at Gallipoli, Turkey 1st/2nd July 1915 Awarded the V.C. for actions at Lens, France 21st August 1917 Born in London, to a Coleraine father and Portadown mother Awarded the V.C. for actions at Hamel 1st July 1916 3. Private William McFadzean 8. Private James Duffy 13. Rifleman Robert Quigg 14th Battalion Royal Irish Rifles 18.