From Colonial Hegemonies to Imperial Conquest, 1840–1880

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Click Here to Download

The Project Gutenberg EBook of South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I, by J. Castell Hopkins and Murat Halstead This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I Comprising a History of South Africa and its people, including the war of 1899 and 1900 Author: J. Castell Hopkins Murat Halstead Release Date: December 1, 2012 [EBook #41521] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOUTH AFRICA AND BOER-BRITISH WAR *** Produced by Al Haines JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN, Colonial Secretary of England. PAUL KRUGER, President of the South African Republic. (Photo from Duffus Bros.) South Africa AND The Boer-British War COMPRISING A HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA AND ITS PEOPLE, INCLUDING THE WAR OF 1899 AND 1900 BY J. CASTELL HOPKINS, F.S.S. Author of The Life and Works of Mr. Gladstone; Queen Victoria, Her Life and Reign; The Sword of Islam, or Annals of Turkish Power; Life and Work of Sir John Thompson. Editor of "Canada; An Encyclopedia," in six volumes. AND MURAT HALSTEAD Formerly Editor of the Cincinnati "Commercial Gazette," and the Brooklyn "Standard-Union." Author of The Story of Cuba; Life of William McKinley; The Story of the Philippines; The History of American Expansion; The History of the Spanish-American War; Our New Possessions, and The Life and Achievements of Admiral Dewey, etc., etc. -

Boer War Association Queensland

Boer War Association Queensland Queensland Patron: Major General Professor John Pearn, AO RFD (Retd) Monumentally Speaking - Queensland Edition Committee Newsletter - Volume 12, No. 1 - March 2019 As part of the service, Corinda State High School student, Queensland Chairman’s Report Isabel Dow, was presented with the Onverwacht Essay Medal- lion, by MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD. The Welcome to our first Queensland Newsletter of 2019, and the messages between Ermelo High School (Hoërskool Ermelo an fifth of the current committee. Afrikaans Medium School), South Africa and Corinda State High School, were read by Sophie Verprek from Corinda State Although a little late, the com- High School. mittee extend their „Compli- ments of the Season‟ to all. MAJGEN Professor John Pearn AO, RFD, together with Pierre The committee also welcomes van Blommestein (Secretary of BWAQ), laid BWAQ wreaths. all new members and a hearty Mrs Laurie Forsyth, BWAQ‟s first „Honorary Life Member‟, was „thank you‟ to all members who honoured as the first to lay a wreath assisted by LTCOL Miles have stuck by us; your loyalty Farmer OAM (Retd). Patron: MAJGEN John Pearn AO RFD (Retd) is most appreciated. It is this Secretary: Pierre van Blommestein Chairman: Gordon Bold. Last year, 2018, the Sherwood/Indooroopilly RSL Sub-Branch membership that enables „Boer decided it would be beneficial for all concerned for the Com- War Association Queensland‟ (BWAQ) to continue with its memoration Service for the Battle of Onverwacht Hills to be objectives. relocated from its traditional location in St Matthews Cemetery BWAQ are dedicated to evolve from the building of the mem- Sherwood, to the „Croll Memorial Precinct‟, located at 2 Clew- orial, to an association committed to maintaining the memory ley Street, Corinda; adjacent to the Sherwood/Indooroopilly and history of the Boer War; focus being descendants and RSL Sub-Branch. -

The Interaction Between the Missionaries of the Cape

THE INTERACTION BETWEEN THE MISSIONARIES OF THE CAPE EASTERN FRONTIER AND THE COLONIAL AUTHORITIES IN THE ERA OF SIR GEORGE GREY, 1854 - 1861. Constance Gail Weldon Pietermaritzburg, December 1984* Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Historical Studies, University of Natal, 1984. CONTENTS Page Abstract i List of Abbreviations vi Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Sir George Grey and his ’civili zing mission’ 16 Chapter 3 The missionaries and Grey 1854-6 55 Chapter 4 The Cattle Killing 1856/7 99 Chanter 5 The Aftermath of the Cattle Killing (till 1860s) 137 Chapter 6 Conclusion 174 Appendix A Principal mission stations on the frontier 227 Appendix B Wesleyan Methodist and Church of Scotland Missionaries 228 Appendix C List of magistrates and chiefs 229 Appendix D Biographical Notes 230 Select Bibliography 233 List of photographs and maps Between pages 1. Sir George Grey - Governor 15/16 2. Map showing Cape eastern frontier and principal military posts 32/33 3. Map showing the principal frontier mission stations 54/55 4. Photographs showing Lovedale trade departments 78/79 5. Map showing British Kaffraria and principal chiefs 98/99 6. Sir George Grey - 'Romantic Imperialist' 143/144 7. Sir George Grey - civilian 225/226 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge with thanks the financial assistance rendered by the Human Sciences Research Council towards the costs of this research. Opinions expressed or conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not to be regarded as those of the Human Sciences Research Council. -

King William's Town

http://ngtt.journals.ac.za Hofmeyr, JW (Hoffie) University of the Free State and Hofmeyr, George S (†) (1945-2009) Former Director of the National Monuments Council of South Africa Establishing a stable society for the sake of ecclesiastical expansion in a frontier capital (King William’s Town) in the Eastern Cape: the pensioners and their village between 1855 and 1861 ABSTRACT For many different reasons, the Eastern Cape area has long been and remains one of the strong focus points of general, political and ecclesiastical historians. In this first article of a series on a frontier capital (King William’s Town) in the Eastern Cape, I wish to focus on a unique socio economic aspect of the fabric of the Eastern Cape society in the period between 1855 and 1861 i.e. the establishment of a Pensioners’ Village. It also touches on certain aspects of the process of colonization in the Eastern Cape. Eventually all of this had, besides many other influences, also an influence on the further expansion of Christianity in the frontier context of the Eastern Cape. In a next article the focus will therefore be on a discussion and analysis of the expansion of missionary work in this frontier context against the background of the establishment of the Pensioners’ Village. 1. INTRODUCTION The British settlement of the Eastern Cape region was a long drawn out process, besides that of the local indigenous people, the Xhosa from the north and the Afrikaner settlers from the western Cape. All these settlements not only had a clear socio economic and political effect but it eventually also influenced the ecclesiastical scene. -

The Development of Appropriate Procedures Towards and After Closure of Underground Gold Mines from a Water Management Perspective

THE DEVELOPMENT OF APPROPRIATE PROCEDURES TOWARDS AND AFTER CLOSURE OF UNDERGROUND GOLD MINES FROM A WATER MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVE Report to the WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION by W Pulles, S Banister and M van Biljon on hehalf of PULLES HOWARD & DE LANGE INCORPORATED RISON GROUNDWATER CONSULTING cc WRC Report No: 1215/1/05 ISBN No: 1-77005-237-2 MARCH 2005 Disclaimer This report emanates from a project financed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and is approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC or the members of the project steering committee, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A need was identified by the Water Research Commission to undertake research into the issue of mine closure planning from a water management perspective in the South African gold mining industry. Initially a project was conceived that was based on undertaking a more detailed study on the development of a coherent and integrated closure planning process for a case study region – the Klerksdorp-Orkney-Stilfontein-Hartebeestfontein (KOSH) area. This approach was eventually abandoned due to the unwillingness of the gold mines in this region (other than Anglogold) to participate in the project. The project methodology was subsequently modified and approved by the project Steering Committee to rather study the complete South African gold mining industry and develop a closure planning methodology that would have application throughout the industry. In support of such an industry-wide study, an assessment would be undertaken of the current status of closure planning contained within the mine EMPRs. -

Eastern Cape Province

S T R E L I T Z I A 41 A Flora of the Eastern Cape Province Christina L. Bredenkamp Volume 3 Pretoria 2019 S T R E L I T Z I A 41 (2019) 1605 250–600 × 15 mm, apex acute to obtuse. Peduncle 600–1 300 mm high. Inflorescence densely flowered; pedicels 30–70 mm long, spreading and somewhat drooping. Perianth purplish blue to deep blue; segments 30–70 mm long, spreading and recurving; tube 10–19 mm long. Stamens with purple pollen. Flowering time Nov.–Feb. Well-drained, rich soil and on grassy slopes; Sub-Escarpment Grassland and Sub-Escarpment Savanna (Oribi Gorge District and Queenstown). praecox Willd. Blue lily; bloulelie, agapant (A); isicakathi (X); ubani (Z) Perennial herb, geophyte, 0.4–1.2 m high. Leaves bright green, evergreen, leathery or flaccid, 7–20 per individual plant, 200–700 × 15–55 mm, apex obtuse or acute. Inflorescence not densely flowered; pedicels 40–120 mm long. Peduncle 400–1 000 mm high. Perianth pale blue or occasionally greyish white; segments 30–70 mm long; tube 7–26 mm long. Stamens with yellow pollen. Flowering time Oct.–Apr. Moist, rich soil; Sub-Escarpment Grassland, Sub-Escarpment Savanna, Indian Ocean Coastal Belt, Albany Thicket, Eastern Fynbos-Renosterveld (Kokstad District S to Port St Johns, King William’s Town, Kentani, Whiskey Creek River, East London and Humansdorp). BAKER, J.G. 1897. Alliaceae. Flora capensis 6: 402–408. DUNCAN, G. 1998. Kirstenbosch Gardening Series. Grow Agapanthus: A guide to the species, cultivation and propagation of the genus Agapanthus. National Botanical Institute, Kirsten- bosch, South Africa. -

Proquest Dissertations

I^fefl National Library Bibliotheque naiionale • T • 0f Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographic Services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) K1A0N4 K1A0N4 v'o,/rM<* Volt? rottiU'iKc Our lilu Nolle tit&rtsnca NOTICE AVIS The quality of this microform is La qualite de cette microforme heavily dependent upon the depend grandement de la qualite quality of the original thesis de la these soumise au submitted for microfilming. microfilmage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualite ensure the highest quality of superieure de reproduction. reproduction possible. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec I'universite degree. qui a confere Ie grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualite d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser a pages were typed with a poor desirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originates ont ete university sent us an inferior dactylographies a I'aide d'un photocopy. ruban use ou si I'univeioite nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualite inferieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, meme partielle, this microform is governed by de cette microforme est soumise the Canadian Copyright Act, a la Loi canadienne sur Ie droit R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30, and d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. C-30, et subsequent amendments. ses amendements subsequents. Canada Maqoma: Xhosa Resistance to the Advance of Colonial Hegemony (1798-1873) by Timothy J. -

Heritage Impact Assessment of Ndlambe and Makana Borrow Pits, Greater Cacadu Region, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF NDLAMBE AND MAKANA BORROW PITS, GREATER CACADU REGION, EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA Assessment and report by For Terreco Consulting Telephone Duncan Scott (043) 721 1502 Box 20057 Ashburton 3213 PIETERMARITZBURG South Africa Telephone 033 326 1136 Facsimile 086 672 8557 082 655 9077 / 072 725 1763 26 September 2008 [email protected] HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF NDLAMBE AND MAKANA BORROW PITS, EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE Management summary eThembeni Cultural Heritage was appointed by Terreco Consulting to undertake a heritage impact assessment of proposed borrow pit extensions and rehabilitation in the Greater Cacadu Region, in terms of the Heritage Resources Act No 25 of 1999. Two eThembeni staff members inspected the borrow pits on 8 and 9 September 2008 and completed controlled-exclusive surface surveys of each. We identified no heritage resources within any of the proposed development areas. The landscape within which the borrow pits are located is one of extensive agriculture and conservation, dominated overwhelmingly by game and hunting farms. Scattered villages, towns and farmsteads are present and infrastructure is generally basic and limited to services that provide for local needs. All the borrow pits will be rehabilitated according to the standards of the Department of Minerals and Energy, to ensure that visual impacts on the landscape are minimized in the long term. We recommend that the development proceed with no further heritage mitigation and have submitted this report to the South African Heritage Resources Agency in fulfilment of the requirements of the Heritage Resources Act 1999. The relevant SAHRA personnel are Dr Antonieta Jerardino (telephone 021 462 4502) and Mr Thanduxolo Lungile (telephone 043 722 1740/2/6). -

Amathole District Municipality

AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY 2012 - 2017 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN Amathole District Municipality IDP 2012-2017 – Version 1 of 5 Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENT The Executive Mayor’s Foreword 4 Municipal Manager’s Message 5 The Executive Summary 7 Report Outline 16 Chapter 1: The Vision 17 Vision, Mission and Core Values 17 List of Amathole District Priorities 18 Chapter 2: Demographic Profile of the District 31 A. Introduction 31 B. Demographic Profile 32 C. Economic Overview 38 D. Analysis of Trends in various sectors 40 Chapter 3: Status Quo Assessment 42 1 Local Economic Development 42 1.1 Economic Research 42 1.2 Enterprise Development 44 1.3 Cooperative Development 46 1.4 Tourism Development and Promotion 48 1.5 Film Industry 51 1.6 Agriculture Development 52 1.7 Heritage Development 54 1.8 Environmental Management 56 1.9 Expanded Public Works Program 64 2 Service Delivery and Infrastructure Investment 65 2.1 Water Services (Water & Sanitation) 65 2.2 Solid Waste 78 2.3 Transport 81 2.4 Electricity 2.5 Building Services Planning 89 2.6 Health and Protection Services 90 2.7 Land Reform, Spatial Planning and Human Settlements 99 3 Municipal Transformation and Institutional Development 112 3.1 Organizational and Establishment Plan 112 3.2 Personnel Administration 124 3.3 Labour Relations 124 3.4 Fleet Management 127 3.5 Employment Equity Plan 129 3.6 Human Resource Development 132 3.7 Information Communication Technology 134 4 Municipal Financial Viability and Management 136 4.1 Financial Management 136 4.2 Budgeting 137 4.3 Expenditure -

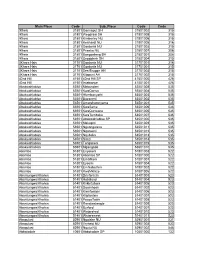

Mainplace Codelist.Xls

Main Place Code Sub_Place Code Code !Kheis 31801 Gannaput SH 31801002 315 !Kheis 31801 Wegdraai SH 31801008 315 !Kheis 31801 Kimberley NU 31801006 315 !Kheis 31801 Kenhardt NU 31801005 316 !Kheis 31801 Gordonia NU 31801003 315 !Kheis 31801 Prieska NU 31801007 306 !Kheis 31801 Boegoeberg SH 31801001 306 !Kheis 31801 Grootdrink SH 31801004 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 316 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Ses-Brugge AH 31701003 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Klippunt AH 31701002 315 42nd Hill 41501 42nd Hill SP 41501000 426 42nd Hill 41501 Intabazwe 41501001 426 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mabundeni 53501008 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQonsa 53501004 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Hlambanyathi 53501003 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Bazaneni 53501002 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Amatshamnyama 53501001 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaSeme 53501006 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQunwane 53501005 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaTembeka 53501007 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Abakwahlabisa SP 53501000 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Makopini 53501009 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Ngxongwana 53501011 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqotweni 53501012 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqubeka 53501013 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Sitezi 53501014 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Tanganeni 53501015 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mgangado 53501010 535 Abambo 51801 Enyokeni 51801003 522 Abambo 51801 Abambo SP 51801000 522 Abambo 51801 Emafikeni 51801001 522 Abambo 51801 Eyosini 51801004 522 Abambo 51801 Emhlabathini 51801002 522 Abambo 51801 KwaMkhize 51801005 522 Abantungwa/Kholwa 51401 Driefontein 51401003 523 -

MA Semester IV- History of South Africa 1850-1950 (HISKM 16) Dr

MA Semester IV- History of South Africa 1850-1950 (HISKM 16) Dr. Mukesh Kumar UNIT-I Early European presence in the cape 1650-1800- The first Europeans to enter Southern Africa were the Portuguese, who from the 15th century edged their way around the African coast in the hope of outflanking Islam, finding a sea route to the riches of India, and discovering additional sources of food. They reached the Kongo Kingdom in northwestern Angola in 1482–83; early in 1488 Bartolomeu Dias rounded the southern tip of the continent; and just over a decade later Vasco da Gama sailed along the east coast of Africa before striking out to India. Although the voyages were initially unpromising, they marked the beginning of the integration of the subcontinent into the new world economy and the dominance of Europeans over the indigenous inhabitants. The Portuguese in west-central Africa Portuguese influence in west-central Africa radiated over a far wider area and was much more dramatic and destructive than on the east coast. Initially the Portuguese crown and Jesuit missionaries forged peaceful links with the kingdom of the Kongo, converting its king to Christianity. Almost immediately, however, slave traders followed in the wake of priests and teachers, and west- central Africa became tied to the demands of the Sao Tome sugar planters and the transatlantic slave trade. Until 1560 the Kongo kings had an effective monopoly in west-central Africa over trade with metropolitan Portugal, which showed relatively little interest in its African possessions. By the 1520s, however, Afro-Portuguese traders and landowners from Sao Tomé were intervening in the affairs of the Ndongo kingdom to the south, supporting the ruler, or ngola, in his military campaigns and taking his war captives and surplus dependents as slaves. -

147 Reports December 2020

147 reports December 2020 Internal parasites Intestinal Roundworms (December 2020) jkccff Balfour, Grootvlei, Lydenburg, Middelburg, Nelspruit, Piet Retief, Standerton, Bapsfontein, Bronkhorstspruit, Hammanskraal, Magaliesburg, Nigel, Onderstepoort, Pretoria, Rayton, Makhado, Brits, Christiana, Potchefstroom, Ventersdorp, Zeerust, Bloemfontein, Bultfontein, Clocolan, Dewetsdorp, Ficksburg, Frankfort, Hertzogville, Hoopstad, Kroonstad, Oranjeville, Reitz, Senekal, Viljoenskroon, Warden, Winburg, Camperdown, Eshowe, Estcourt, Mtubatuba, Pietermaritzburg, Cradock, Graaff-Reinet, Humansdorp, Witelsbos, Caledon, George, Heidelberg, Riversdale, Stellenbosch, Vredenburg, Wellington, Colesberg, Kimberley Internal parasites – Resistant roundworms (December 2020) jkccff Pretoria, Bloemfontein, Hoopstad, Reitz, Eshowe, Underberg x Internal parasites – Tapeworms (December 2020)jkccff Balfour, Middelburg, Nelspruit, Standerton, Bapsfontein, Magaliesburg, Pretoria, Polokwane, Bloemfontein, Clocolan, Kroonstad, Memel, Reitz, Underberg, Graaff-Reinet, Humansdorp 00 Internal parasites – Tapeworms Cysticercosis (measles) (December 2020) jkccff Volksrust, Bronkhorstspruit, Mokopane, George, Paarl, Kimberley 00 Internal parasites – Liver fluke worms (December 2020)jkccff Bethlehem, Reitz, Winburg, Underberg, George, Malmesbury Internal parasites – Conical fluke (December 2020) jkccff Nigel, Kroonstad, Reitz, Winburg, Pietermaritzburg, Vryheid Internal parasites – Parafilaria (December 2020) jkccff Volksrust, Nigel, Stella, Mtubatuba, Vryheid Blue ticks (December