Distance, Magnetic Field and Kinematics of a Filamentary Cloud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

145, September 2010

British Astronomical Association VARIABLE STAR SECTION CIRCULAR No 145, September 2010 Contents EG Andromedae Light Curve ................................................... inside front cover From the Director ............................................................................................... 1 Letter Page. Visual Observing ............................................................................ 4 Epsilon Aurigae Spectroscopically at Mid Eclipse .......................................... 5 Eclipsing Binary News ...................................................................................... 7 AO Cassiopeiae Phase Diagram ............................................................ 9 PV Cephei and Gyulbudaghian’s Nebula ........................................................ 10 WR140 Periastron Campaign Update .............................................................. 12 VSS Meeting, Pendrell Hall. The Central Stars of Planetary Nebulae ............ 14 RR Coronae Borealis 1993-2004 ...................................................................... 16 TU Cassiopeiae Phase Diagram 2005-2010 ..................................................... 18 Binocular Priority List ..................................................................................... 19 Eclipsing Binary Predictions ............................................................................ 20 Charges for Section Publications .............................................. inside back cover Guidelines for Contributing to the Circular ............................. -

Academic Reading in Science Copyright 2014 © Chris Elvin Copyright Notice

Academic Reading in Science Copyright 2014 © Chris Elvin Copyright Notice Academic Reading in Science contains adaptations of Wikipedia copyrighted material. All pages containing these adaptations can be identified by the logo below; This logo is visible at the foot of every page in which Wikipedia articles have been adapted. Furthermore, all adaptations of Wikipedia sources show a URL at the foot of the article which you may use to access the original article. Pages which do not show the logo above are the copyright of the author Chris Elvin, and may not be used without permission. Creative Commons Deed You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute and transmit the work, and to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work.) Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same, similar or a compatible license. With the understanding that: Waiver—Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Other Rights—In no way are any of the following rights affected by the license: your fair dealing or fair use rights; the author’s moral rights; and rights other persons may have either in the work itself or in how the work is used, such as publicity or privacy rights. Notice—For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. -

Alyssa Goodman, Naomi Ridge, Scott Wolk, Scott Schnee, Di Li & Bryan

COMPLET(E)ING THE STAR-FORMATION HISTORY OF THE RHO-OPH REGION Alyssa Goodman, Naomi Ridge, Scott Wolk, Scott Schnee, Di Li & Bryan Gaensler Background The interaction of newly formed stars with their parent cloud, particularly in the case of massive stars, can have significant consequences for the subsequent development of the cloud. Hot, massive stars will cause cloud disruption through their ionizing flux as well as through the momentum in their stellar winds. Alternatively, given the right conditions in the cloud, stellar winds may also cause the collapse of cloud cores and induce further star formation. Located only 160pc from the Sun, the Ophiuchus molecular cloud is one of the most conspicuous nearby regions where low- and intermediate-mass star formation is taking place (e.g. Wilking 1992 for a review). The Ophiuchus cloud consists of two massive, centrally condensed cores, L1688 and L1689, from each of which a filamentary system of streamers extends to the north-east over tens of parsecs (e.g. Loren 1989). While little star formation activity is observed in the streamers, the westernmost core, L1688 (figure 1), harbors a rich cluster of young stellar objects (YSOs) at various evolutionary stages and is distinguished by a high star-formation efficiency (Wilking & Lada 1983 - hereafter WL83). This young stellar cluster and the cloud core in which it resides are commonly referred to as the ρ-Oph star-forming region. Both the gas/dust content and the embedded stellar population of ρ−Oph have been extensively studied for more than two decades. The distribution of the low-density molecular gas was mapped in C18O(1-0) by WL83, revealing a ridge of high column density gas. -

Filter Performance Comparisons for Some Common Nebulae

Filter Performance Comparisons For Some Common Nebulae By Dave Knisely Light Pollution and various “nebula” filters have been around since the late 1970’s, and amateurs have been using them ever since to bring out detail (and even some objects) which were difficult to impossible to see before in modest apertures. When I started using them in the early 1980’s, specific information about which filter might work on a given object (or even whether certain filters were useful at all) was often hard to come by. Even those accounts that were available often had incomplete or inaccurate information. Getting some observational experience with the Lumicon line of filters helped, but there were still some unanswered questions. I wondered how the various filters would rank on- average against each other for a large number of objects, and whether there was a “best overall” filter. In particular, I also wondered if the much-maligned H-Beta filter was useful on more objects than the two or three targets most often mentioned in publications. In the summer of 1999, I decided to begin some more comprehensive observations to try and answer these questions and determine how to best use these filters overall. I formulated a basic survey covering a moderate number of emission and planetary nebulae to obtain some statistics on filter performance to try to address the following questions: 1. How do the various filter types compare as to what (on average) they show on a given nebula? 2. Is there one overall “best” nebula filter which will work on the largest number of objects? 3. -

Správa O Činnosti Organizácie SAV Za Rok 2017

Astronomický ústav SAV Správa o činnosti organizácie SAV za rok 2017 Tatranská Lomnica január 2018 Obsah osnovy Správy o činnosti organizácie SAV za rok 2017 1. Základné údaje o organizácii 2. Vedecká činnosť 3. Doktorandské štúdium, iná pedagogická činnosť a budovanie ľudských zdrojov pre vedu a techniku 4. Medzinárodná vedecká spolupráca 5. Vedná politika 6. Spolupráca s VŠ a inými subjektmi v oblasti vedy a techniky 7. Spolupráca s aplikačnou a hospodárskou sférou 8. Aktivity pre Národnú radu SR, vládu SR, ústredné orgány štátnej správy SR a iné organizácie 9. Vedecko-organizačné a popularizačné aktivity 10. Činnosť knižnično-informačného pracoviska 11. Aktivity v orgánoch SAV 12. Hospodárenie organizácie 13. Nadácie a fondy pri organizácii SAV 14. Iné významné činnosti organizácie SAV 15. Vyznamenania, ocenenia a ceny udelené organizácii a pracovníkom organizácie SAV 16. Poskytovanie informácií v súlade so zákonom o slobodnom prístupe k informáciám 17. Problémy a podnety pre činnosť SAV PRÍLOHY A Zoznam zamestnancov a doktorandov organizácie k 31.12.2017 B Projekty riešené v organizácii C Publikačná činnosť organizácie D Údaje o pedagogickej činnosti organizácie E Medzinárodná mobilita organizácie F Vedecko-popularizačná činnosť pracovníkov organizácie SAV Správa o činnosti organizácie SAV 1. Základné údaje o organizácii 1.1. Kontaktné údaje Názov: Astronomický ústav SAV Riaditeľ: Mgr. Martin Vaňko, PhD. Zástupca riaditeľa: Mgr. Peter Gömöry, PhD. Vedecký tajomník: Mgr. Marián Jakubík, PhD. Predseda vedeckej rady: RNDr. Luboš Neslušan, CSc. Člen snemu SAV: Mgr. Marián Jakubík, PhD. Adresa: Astronomický ústav SAV, 059 60 Tatranská Lomnica http://www.ta3.sk Tel.: 052/7879111 Fax: 052/4467656 E-mail: [email protected] Názvy a adresy detašovaných pracovísk: Astronomický ústav - Oddelenie medziplanetárnej hmoty Dúbravská cesta 9, 845 04 Bratislava Vedúci detašovaných pracovísk: Astronomický ústav - Oddelenie medziplanetárnej hmoty prof. -

Successful Observing Sessions HOWL-EEN FUN Kepler’S Supernova Remnant Harvard’S Plate Project and Women Computers

Published by the Astronomical League Vol. 69, No. 4 September 2017 Successful Observing Sessions HOWL-EEN FUN Kepler’s Supernova Remnant Harvard’s Plate Project and Women Computers T HE ASTRONOMICAL LEAGUE 1 he 1,396th entry in John the way to HR 8281, is the Dreyer’s Index Catalogue of Elephant’s Trunk Nebula. The T Nebulae and Clusters of left (east) edge of the trunk Stars is associated with a DEEP-SKY OBJECTS contains bright, hot, young galactic star cluster contained stars, emission nebulae, within a large region of faint reflection nebulae, and dark nebulosity, and a smaller region THE ELEPHANT’S TRUNK NEBULA nebulae worth exploring with an within it called the Elephant’s 8-inch or larger telescope. Trunk Nebula. In general, this By Dr. James R. Dire, Kauai Educational Association for Science & Astronomy Other features that are an entire region is absolute must to referred to by the check out in IC pachyderm 1396 are the proboscis phrase. many dark IC 1396 resides nebulae. Probably in the constellation the best is Cepheus and is Barnard 161. This located 2,400 light- dark nebula is years from Earth. located 15 To find IC 1396, arcminutes north start at Alpha of SAO 33652. Cephei, a.k.a. The nebula Alderamin, and go measures 5 by 2.5 five degrees arcminutes in southeast to the size. The nebula is fourth-magnitude very dark. Myriad red star Mu Cephei. Milky Way stars Mu Cephei goes by surround the the Arabic name nebula, but none Erakis. It is also can be seen in called Herschel’s this small patch of Garnet Star, after the sky. -

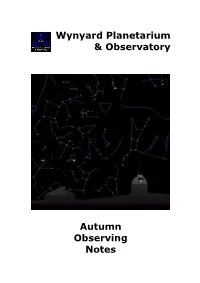

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory a Autumn Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory A Autumn Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye CASSIOPEIA Look for the ‘W’ 4 shape 3 Polaris URSA MINOR Notice how the constellations swing around Polaris during the night Pherkad Kochab Is Kochab orange compared 2 to Polaris? Pointers Is Dubhe Dubhe yellowish compared to Merak? 1 Merak THE PLOUGH Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in autumn. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 1.2 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. Close to the horizon is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan with the handle stretching to your left. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The two right-hand stars are called the Pointers. Can you tell that the higher of the two, Dubhe is slightly yellowish compared to the lower, Merak? Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white- hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you upwards to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the left are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. -

物理雙月刊29-3 621-772.Pdf

ᒳृݧ ʳ ౨ᄭઝݾറᙀ ᚮࣔᏕ/֮ ΔࢨუԵᛵᇞݺଚشଶಬߨጿጿլឰऱਞ ၦऱࠌ ౨ᄭऱ࣠Δኙ٤شॸΔ᠏ณհၴԾࠩԱքΕԮִ መ৫ࠌ ഏᎾၴऱڇऱᐙګԳพஒऱ ᛩቼࢬທח᥆࣍ङऱֲΔ עء۶ΔլោᥦԫՀڕټᚰۖࠐΖ ඈچᑷԫंंլឰ Δᑷ รԼᒧറ֮ΚψൕഏᎾᛩቼਐᑇࡌ௧ᛩ៥ऱ ऱ࿇ሽ౨ᄭऱᛘΔ ֗ IEA อૠװထԫैཀհլ݈ ωΔᇠᒧ֮ີტխᘋՕᖂ܉ऱՕհխΔᨃԳ ։ᗺ៥࣍ ᤚຑ़Εຑ௧ຟआᤴ ढߓ୪ւࣳඒ࣍ඒᖂઔߒ խࢼ़ݺଚᐷᐊΖڦۍऱ ᎩհᎾΔڼԱΖՈࠌଖ ᆖᛎࡉഏԺऱ࿇୶זᆏᆏՂ چሽլឰشڞऱ ᎅ࠷ެ࣍౨ᄭױሽ ፖᑓΔ༓شڇΔኚ໌ΖྥۖΔ֒ Δޡݾऱၞشࠡሎ֗شழΔݺଚՈՕ ऱࠌٵཚऱ ᎅਢԫഏᆖᛎ࿇୶ऱױCO2 ऱඈ࣋ၦࡉᄵயᚨ ౨ᄭ ٺΔ౨ᄭᤜᠲኙ࣍ڼڂऱ༞֏ΔထኔఎՀԱլ֟լߜ ೯ԺΖ ࡳࢤެڶᏆऱ࿇୶ࠠٺڇᄊ֏ ഏچຒףԱګऱધᙕΔՈ ߪᣂএࠩԫषᄎՕฒऱ壂ઘࡉֲൄढ֊ޓயᚨऱං֫հԫΖ ऱᐙΔ ฒاڇवኙ࣍ Ꮭऱं೯ΖᅝഏᎾईᏝՂཆΔഏփढᏝঁஓஓױݺଚࠆ࠹ԫաऱ堚ළፖঁ൸հᎾΔڇ ՂይΖچΔ ऱৼᜢխᆥྤݲᐫᇷᄭᤖ៲ຆΔ౨ᄭ༓٤ᑇٛᘸၞՑऱྥ֚ 9 ڣ ࣍ 2005ޓࠐΔईᏝᆏᆏ֒Δڣၦথբ २༓شࢬऱؓ݁ሽၦࡉ౨ᄭࠌڣޢԳޢݺଚ ද࣍ US$70 ऱ໌ޢࠐऱᖵᄅΔሒڣۍሽ ִٝડధڇ౨ᄭΕڇऱছૄΜૉ൞უڇټਢඈ ᄭ۞ᖏञࡉైڂຝ։ڶᄅધᙕΖईᏝऱं೯ឈ ᚮࣔᏕ ౨ᄭفՂ֏چլ؆ਢڂԫ܀ਙएࠃٙΔ 堚ဎՕᖂढߓمഏ ڶईΕ֚ྥࡉᅁ౨ᄭᗏற)ऱᤖ៲ၦึߒفऑਐ) E-mail: [email protected] ࢤΔૉشऱ౨ᄭࠌڶૻΖറ୮ေ۷ૉᖕԳᣊ Ϯ621Ϯʳ քִʳڣ ˊ˃˃˅ʻ֥࠴Կཚʼʳעढᠨִ ᒳृݧ ༚ྼऱႨΖᅝᓫᓵᇠ֘ுΛࢨਢᇠᖑுΛംᠲڶۖ ࠩބயऱᆏ౨ֱூΔࢨլᕣݶ༈ڶإటנ༼౨آᙈᙈ ᇞு౨ᗏறऱ፹ທመچհছΔषᄎՕฒᚨᇠ٣堚ᄑ ڶՂೈᅁᇷᄭࡸچ౨ᄭऱᇩΔঞזࠠயհཙ ؆ਜ਼ழऱۆுᘿ୴֗אΔ܂࿓ࡉு౨࿇ሽऱՠ فईࡉ֚ྥ֏فڕהऱᤖ៲ၦ؆Δࠡ׳ؐڣ 200 ࢤড়ᨠऱኪ৫אթ౨ڼڕୌࠄΔڶՂऱ ᥨൻਜࠩࢍאڣ ౨ྤऄ֭ᐶመ 50ױၦቃ۷ژᗏறऱᚏ ཚءΔڼڂᖗΖހᒔऱإԫנு౨࿇ሽشࠌܡၦΖ ਢޣ౨ᄭ᜔Ꮑ ሽֆுԿᐗૠቤิ९ದ໑Փऱᑷ֧֨ᗏ ܑຘመف᠏ངயለհႚอ֏܅ءګΔᆖᛎۖྥ ሽֆு౨࿇ሽኔ೭ᆖ᧭ऱڣڍڶࠩԱٍࠠބऱሽ౨ Δشऴ൷ࠌאԫՕฒګ᠏ངڇΔشறऱࠌ ،ݺଚ֮റ૪ψࢢسࢨᑷ౨ऱመ࿓խΔᄎ ு֨ᛜሎᓰᓰ९׆ᐚᆠ٣(شԺ࿇ሽ)Ε೯౨(ሎᙁ־อጠ) ॺൄ᧩࣐ᚩऱאԱᇞ،--ு౨࿇ሽᓫωΔᇠ֮ڕլ ۆᎨॸΔᖄીᣤૹऱᛩቼګඈ࣋Օၦऱᄵ᧯ࡉݮ ຝٺᎅࣔԱு౨࿇ሽऱچᦰृ堚ᄑڗऱؓ݁ᄵ৫ 壄֮چࡉֲᣤૹऱᄵயᚨΔၞۖᖄી ኪؓᘝ ੌ࿓ࡉுᗏறՄऱ፹ທመ࿓Δਢԫᒧॺൄଖԫᦰऱسऱڶऱ۞ྥᛩቼࡉچኙۖڂດዬՂ֒Ζ ኪᛩቼ૿ ֮ີΖسऱچऱᣤૹᓢᚰΔࠌڃனױլګؘലທ ٤ᤜᠲǵഏᎾईᏝࡺլڜईفᜯ؎ՕऱਗᖏΖ ࠹ࠩ٤ ՂഏᎾၴᒤᄵ᧯ඈ࣋྇ၦࢭᘭհᛩঅֆףࡉଢऱ᧢ᔢࢬທ ՀΔ᧢ޏኙᛩቼऱشᣂ౨ᄭሎڶ ڂᛩঅრᢝይ֗אඔ೯ΔڤإऱᐙຍଡૹᤜᠲΔݺଚܑࡡᓮՠᄐݾઔߒ પψࠇຟᤜࡳωګ ԳᣊؘߨհሁΖ۶ᘯګ౨ᄭسᡖᐚ ైऱᓢᚰՀΔං೯٦ۂ(Հ១ጠՠઔೃ౨ᛩࢬא)ೃ౨ᄭፖᛩቼઔߒࢬ ౨ᄭ࿇ሽωٍᆖسรքᒧറ֮ψ٦עء౨ᄭΛس٦ -

Nebula in NGC 2264

Durham E-Theses The polarisation of the cone(IRN) Nebula in NGC 2264 Hill, Marianne C.M. How to cite: Hill, Marianne C.M. (1991) The polarisation of the cone(IRN) Nebula in NGC 2264, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6098/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE POLARISATION OF THE CONE(IRN) NEBULA IN NGC 2264 MARIANNE C. M. HILL A Thesis submitted to the University of Durham for the degree of Master of Science. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without prior consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Department of Physics. September 1991 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

LIST of PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute of Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India) Manora Peak, Naini Tal - 263 129, India (1955−2020) ABBREVIATIONS AA: Astronomy and Astrophysics AASS: Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series ACTA: Acta Astronomica AJ: Astronomical Journal ANG: Annals de Geophysique Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal ASP: Astronomical Society of Pacific ASR: Advances in Space Research ASS: Astrophysics and Space Science AE: Atmospheric Environment ASL: Atmospheric Science Letters BA: Baltic Astronomy BAC: Bulletin Astronomical Institute of Czechoslovakia BASI: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India BIVS: Bulletin of the Indian Vacuum Society BNIS: Bulletin of National Institute of Sciences CJAA: Chinese Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics CS: Current Science EPS: Earth Planets Space GRL : Geophysical Research Letters IAU: International Astronomical Union IBVS: Information Bulletin on Variable Stars IJHS: Indian Journal of History of Science IJPAP: Indian Journal of Pure and Applied Physics IJRSP: Indian Journal of Radio and Space Physics INSA: Indian National Science Academy JAA: Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy JAMC: Journal of Applied Meterology and Climatology JATP: Journal of Atmospheric and Terrestrial Physics JBAA: Journal of British Astronomical Association JCAP: Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics JESS : Jr. of Earth System Science JGR : Journal of Geophysical Research JIGR: Journal of Indian -

The Impact of Giant Stellar Outflows on Molecular Clouds

The Impact of Giant Stellar Outflows on Molecular Clouds A thesis presented by H´ector G. Arce Nazario to The Department of Astronomy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Astronomy Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts October, 2001 c 2001, by H´ector G. Arce Nazario All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Thesis Advisor: Alyssa A. Goodman Thesis by: H´ector G. Arce Nazario We use new millimeter wavelength observations to reveal the important effects that giant (parsec-scale) outflows from young stars have on their surroundings. We find that giant outflows have the potential to disrupt their host cloud, and/or drive turbulence there. In addition, our study confirms that episodicity and a time-varying ejection axis are common characteristics of giant outflows. We carried out our study by mapping, in great detail, the surrounding molecular gas and parent cloud of two giant Herbig-Haro (HH) flows; HH 300 and HH 315. Our study shows that these giant HH flows have been able to entrain large amounts of molecular gas, as the molecular outflows they have produced have masses of 4 to 7 M |which is approximately 5 to 10% of the total quiescent gas mass in their parent clouds. These outflows have injected substantial amounts of −1 momentum and kinetic energy on their parent cloud, in the order of 10 M km s and 1044 erg, respectively. We find that both molecular outflows have energies comparable to their parent clouds' turbulent and gravitationally binding energies. In addition, these outflows have been able to redistribute large amounts of their surrounding medium-density (n ∼ 103 cm−3) gas, thereby sculpting their parent cloud and affecting its density and velocity distribution at distances as large as 1 to 1.5 pc from the outflow source. -

Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium

Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium Ralf S. Klessen and Simon C. O. Glover Abstract Interstellar space is filled with a dilute mixture of charged particles, atoms, molecules and dust grains, called the interstellar medium (ISM). Understand- ing its physical properties and dynamical behavior is of pivotal importance to many areas of astronomy and astrophysics. Galaxy formation and evolu- tion, the formation of stars, cosmic nucleosynthesis, the origin of large com- plex, prebiotic molecules and the abundance, structure and growth of dust grains which constitute the fundamental building blocks of planets, all these processes are intimately coupled to the physics of the interstellar medium. However, despite its importance, its structure and evolution is still not fully understood. Observations reveal that the interstellar medium is highly tur- bulent, consists of different chemical phases, and is characterized by complex structure on all resolvable spatial and temporal scales. Our current numerical and theoretical models describe it as a strongly coupled system that is far from equilibrium and where the different components are intricately linked to- gether by complex feedback loops. Describing the interstellar medium is truly a multi-scale and multi-physics problem. In these lecture notes we introduce the microphysics necessary to better understand the interstellar medium. We review the relations between large-scale and small-scale dynamics, we con- sider turbulence as one of the key drivers of galactic evolution, and we review the physical processes that lead to the formation of dense molecular clouds and that govern stellar birth in their interior. Universität Heidelberg, Zentrum für Astronomie, Institut für Theoretische Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle-Straße 2, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 1 Contents Physical Processes in the Interstellar Medium ...............