Clint Eastwoods's Letters from Iwo Jima As a Transnational Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empires in Flames

Empires in Flames The Pacific and Far East Written by: Andy Chambers Edited by: Alessio Cavatore, Rick Priestley and Paul Sawyer Cover artwork: Peter Dennis Interior artwork: Peter Dennis, Steve Noon, Richard Sample file Chasemore, Stephen Walsh and Stephen Andrew. Photography: Bruno Allanson, Warwick Kinrade, Mark Owen, Paul Sawyer, and Gabrio Tolentino Miniatures painted by: Andres Amian Fernandez, Gary Martin, Bruce Murray, Darek Wyrozebski, and Claudia Zuminich Thanks to: Paul Beccarelli for help with the Chinese army lists, Bruno Allanson for images of his collection of militaria and John Stallard for his love of Gurkhas. OSPREY PUBLISHING ospreypublishing.com warlordgames.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com Contents What Is This Book? 6 Armies of China 31 Army Special Rules 32 The Pacific and Far East 7 Flag 32 Levy 32 The Second Sino-Japanese War 9 Sparrow Tactics (Communists only) 32 Prelude 10 Bodyguard (Nationalists and Warlords only) 32 1937 12 Legends of China: General Sun Li-Jen 32 Marco Polo Bridge 12 Headquarters Units 34 The Battle of Shanghai 12 Nationalist Officer 34 The Rape of Nanking 13 Warlord 34 Communist Officer 34 1938 14 Political Officer 35 Battle of Tai’erzhuang 14 Medic 35 1939 15 Forward Observer 35 The Nomonhan Incident 1939 15 Infantry Squads and Teams 35 World War II in China 15 German-Trained Nationalist Squad 35 Operation August Storm: The Soviet Invasion of Manchuria 16 Infantry Squad 35 Aftermath 18 Conscript Squad 36 X and Y Force Squad (Burma) 36 Fighting the Campaign Using Bolt Action -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Lewis Milestone Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8r78gk6 No online items Lewis Milestone papers Special Collections Margaret Herrick Library© 2016 Lewis Milestone papers 6 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Lewis Milestone papers Date (inclusive): 1926-1978 Date (bulk): 1930s-1963 Collection number: 6 Creator: Milestone, Lewis Extent: 9 linear feet of papers.1 linear feet of photographs.3 artworks Repository: Margaret Herrick Library. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Languages: English Access Available by appointment only. Publication rights Property rights to the physical object belong to the Margaret Herrick Library. Researchers are responsible for obtaining all necessary rights, licenses, or permissions from the appropriate companies or individuals before quoting from or publishing materials obtained from the library. Preferred Citation Lewis Milestone papers, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Acquisition Information Gift of Lewis Milestone, 1979 Biography Lewis Milestone was a Russian-born director and producer whose film career spanned 1921 to 1965. He emigrated to the United States in 1913. OF MICE AND MEN (1939), LES MISERABLES (1952), and MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY (1962) are among his film credits. Milestone received Academy Awards for directing ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT (1930) and TWO ARABIAN KNIGHTS (1927), and was nominated for directing THE FRONT PAGE (1931). Collection Scope and Content Summary The Lewis Milestone papers span the years 1926-1978 (bulk 1930s-1963) and encompass 9 linear feet of manuscripts, 1 linear foot of photographs and 3 artworks. The collection contains production files (scripts and some production material); correspondence; contracts; membership certificates; an incomplete portion of Milestone's autobiography supplemented by material he gathered for that project; scrapbooks and drawings. -

LETTERS from IWO JIMA Wettbewerb LETTERS from IWO JIMA Außer Konkurrenz LETTRES D’IWO JIMA Regie: Clint Eastwood

Berlinale 2007 LETTERS FROM IWO JIMA Wettbewerb LETTERS FROM IWO JIMA Außer Konkurrenz LETTRES D’IWO JIMA Regie: Clint Eastwood USA 2006 Darsteller General Kuribayashi Ken Watanabe Länge 141 Min. Saigo Kazunari Ninomiya Format 35 mm, Baron Nishi Tsuyoshi Ihara Cinemascope Shimizu Ryo Kase Farbe Leutnant Ito Shidou Nakamura Leutnant Fujita Hiroshi Watanabe Stabliste Kapitän Tanida Takumi Bando Buch Iris Yamashita, nach Nozaki Yuki Matsuzaki einer Idee von Iris Kashiwara Takashi Yamaguchi Yamashita und Paul Leutnant Okubo Eijiro Ozaki Haggis sowie den Hanako Nae „Picture Letters“ von Admiral Ohsugi Nobumasa Sakagami Tadamichi Sam Lucas Elliot Kuribayashi Sanitäter Endo Sonny Seiichi Saito Kamera Tom Stern Oberst Oiso Hiro Abe Kameraführung Stephen S. Campanelli Kameraassistenz Bill Coe Schnitt Joel Cox Gary D. Roach Ken Kasai, Masashi Nagadoi, Hiroshi Watanabe, Ken Watanabe Schnittassistenz Michael Cipriano Blu Murray Ton Flash Deros LETTERS FROM IWO JIMA Mischung Walt Martin Vor 62 Jahren trafen die amerikanischen und japanischen Truppen auf Musik Kyle Eastwood Iwo Jima aufeinander. Jahrzehnte später fand man Hunderte von Briefen in Michael Stevens der Erde der kargen Insel. Durch diese Briefe bekommen die Männer, die Production Design Henry Bumstead dort unter Führung ihres außergewöhnlichen Generals gekämpft haben, James J. Murakami Ausstattung Gary Fettis Gesicht und Stimme. Spezialeffekte Michael Owens Als die japanischen Soldaten nach Iwo Jima geschickt werden, wissen sie, Kostüm Deborah Hopper dass sie aller Wahrscheinlichkeit nach nicht zurückkehren werden. Zu ihnen Maske Tania McComas gehört der Bäcker Saigo, der überleben möchte, um seine neugeborene Regieassistenz Donald Murphy Tochter sehen zu können. Baron Nishi, der 1936 als Reiter bei den Olym pi - Katie Carroll Casting Phyllis Huffman schen Spielen in Berlin siegte, gehört ebenso dazu wie der idealistische Ex- Produzenten Clint Eastwood Polizist Shimizu und der von der Sache überzeugte Leut nant Ito. -

Soil“ Traveling in Time and Space

„Soil“ Traveling in time and space Lecture for Writers for Europe Prague Session 2018 By Jochen Brunow Soil. When I first heard the title for the Prague session of Writers For Europe, I marveled at how wonderfully specific and inspiring it would be for writing a screenplay. And when I was asked to give the keynote speech a whole lot of associations and mental images rushed through my mind immediately — memories of very different movies popped up. Scenes and sequences dashed by, as well as the recollection of many personal experiences. All of mankind works on soil, names it and describes it in different ways. We walk on soil, explore and discover it. We feel the soil and touch soil, we dig deep into it and build on it. Soil has a smell, a color and a sound. It evokes names and pictures and even history. Therefore soil can be read like a book. Actually, I think soil might be one of the most central ideas and concepts in religion, mythology, spirituality, science, even in ideology and politics. And because of this, it is very present in all forms of art. Being faced with this enormous amount of content, I was worried about how to find a framework for my lecture. But since I am a writer and not a scientist, I will be speaking as a screenwriter to fellow screenwriters and filmmakers. In the following, I will approach the idea of soil as if my task was to write a screenplay about it. Whenever I think about writing a film on a certain topic, I start to ask myself questions. -

Filmography of Case Study Films (In Chronological Order of Release)

FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS (IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER OF RELEASE) Kairo / Pulse 118 mins, col. Released: 2001 (Japan) Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Screenplay: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Cinematography: Junichiro Hayashi Editing: Junichi Kikuchi Sound: Makio Ika Original Music: Takefumi Haketa Producers: Ken Inoue, Seiji Okuda, Shun Shimizu, Atsuyuki Shimoda, Yasuyoshi Tokuma, and Hiroshi Yamamoto Main Cast: Haruhiko Kato, Kumiko Aso, Koyuki, Kurume Arisaka, Kenji Mizuhashi, and Masatoshi Matsuyo Production Companies: Daiei Eiga, Hakuhodo, Imagica, and Nippon Television Network Corporation (NTV) Doruzu / Dolls 114 mins, col. Released: 2002 (Japan) Director: Takeshi Kitano Screenplay: Takeshi Kitano Cinematography: Katsumi Yanagijima © The Author(s) 2016 217 A. Dorman, Paradoxical Japaneseness, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-55160-3 218 FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS… Editing: Takeshi Kitano Sound: Senji Horiuchi Original Music: Joe Hisaishi Producers: Masayuki Mori and Takio Yoshida Main Cast: Hidetoshi Nishijima, Miho Kanno, Tatsuya Mihashi, Chieko Matsubara, Tsutomu Takeshige, and Kyoko Fukuda Production Companies: Bandai Visual Company, Offi ce Kitano, Tokyo FM Broadcasting Company, and TV Tokyo Sukiyaki uesutan jango / Sukiyaki Western Django 121 mins, col. Released: 2007 (Japan) Director: Takashi Miike Screenplay: Takashi Miike and Masa Nakamura Cinematography: Toyomichi Kurita Editing: Yasushi Shimamura Sound: Jun Nakamura Original Music: Koji Endo Producers: Nobuyuki Tohya, Masao Owaki, and Toshiaki Nakazawa Main Cast: Hideaki Ito, Yusuke Iseya, Koichi Sato, Kaori Momoi, Teruyuki Kagawa, Yoshino Kimura, Masanobu Ando, Shun Oguri, and Quentin Tarantino Production Companies: A-Team, Dentsu, Geneon Entertainment, Nagoya Broadcasting Network (NBN), Sedic International, Shogakukan, Sony Pictures Entertainment (Japan), Sukiyaki Western Django Film Partners, Toei Company, Tokyu Recreation, and TV Asahi Okuribito / Departures 130 mins, col. -

LETTERS AS JOURNALISM DEVICE to REVEAL the WAR in IWO JIMA ISLAND AS REFLECTED in EASTWOOD's FILM Letters from Iwo Jima SEMARA

LETTERS AS JOURNALISM DEVICE TO REVEAL THE WAR IN IWO JIMA ISLAND AS REFLECTED IN EASTWOOD’S FILM Letters from Iwo Jima a Final Project Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English by GHINDA RAKRIAN PATIH 2250405530 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS SEMARANG STATE UNIVERSITY 2009 APPROVAL This final project was approved by the Board of the Examination of the English Department of Faculty of Languages and Arts of Semarang State University on September 14, 2009. Board of Examination 1. Chairman Drs. Januarius Mujiyanto, M.Hum NIP. 195312131983031002 2. Secretary Drs. Alim Sukrisno, M. A __________________ NIP. 195206251981111001 3. First Examiner Rini Susanti, S.S, M. Hum __________________ NIP. 197406252000032001 4. Second Advisor as Second Examiner Dr. Djoko Sutopo, M. Si __________________ NIP. 195403261986011001 5. First Advisor as Third Examiner Dra. Indrawati, M.Hum __________________ NIP. 195410201986012001 Approved by Dean of Faculty of Languages and Arts Prof. Dr. Rustono NIP.195801271983031003 ii PERNYATAAN Dengan ini saya: Nama : Ghinda Rakrian Patih NIM : 2250405530 Prodi/Jurusan : Sastra Inggris/Bahasa dan Sastra Inggris Fakultas Bahasa dan Seni Universitas Negeri Semarang menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa skripsi/tugas akhir/final project yang berjudul: LETTER AS JOURNALISM DEVICE TO REVEAL THE WAR IN IWO JIMA ISLAND AS REFLECTED IN EASTWOOD’S FILM LETTERS FROM IWO JIMA yang saya tulis dalam rangka memenuhi salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar sarjana sastra ini benar-benar merupakan karya saya sendiri, yang saya hasilkan setelah melalui penelitian, bimbingan, diskusi, dan pemaparan/ujian. Semua kutipan baik yang langsung maupun tidak langsung, baik yang diperoleh dari sumber kepustakaan, wahana elektronik, wawancara langsung maupun sumber lainnya, telah disertai keterangan mengenai identitas sumbernya dengan cara sebagaimana yang lazim dalam penelitian karya ilmiah. -

Toshio Masuda (Director) ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… قائمة (ÙÙ ŠÙ„موغراÙÙ ŠØ§)

Toshio Masuda (director) ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… قائمة (ÙÙ ŠÙ„موغراÙÙ ŠØ§) Taking The Castle https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/taking-the-castle-11426062/actors Earthshaking Event https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/earthshaking-event-21015474/actors We Live Today https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/we-live-today-55529320/actors The Perfect Game https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-perfect-game-106350747/actors The Battle of Port https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-battle-of-port-arthur-10880293/actors Arthur Be Forever Yamato https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/be-forever-yamato-1093707/actors Future War 1986 https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/future-war-1986-11199898/actors This Story of Love https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/this-story-of-love-11266725/actors Loving https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/loving-11291142/actors High Teen Boogie https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/high-teen-boogie-11326041/actors The Imperial https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-imperial-japanese-empire-11435655/actors Japanese Empire Heavenly Sin https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/heavenly-sin-11442411/actors Sure Death 5 https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sure-death-5-11490650/actors Love: Take Off https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/love%3A-take-off-11493431/actors Battle Anthem https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/battle-anthem-11508488/actors The Great https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-great-shogunate-battle-11551008/actors Shogunate Battle -

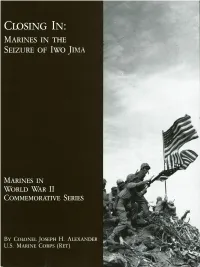

Closingin.Pdf

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead. -

The Media and Reserve Library, Located on the Lower Level West Wing, Has Over 9,000 Videotapes, Dvds and Audiobooks Covering a Multitude of Subjects

Libraries WAR The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days to D-Day DVD-0690 Anthropoid DVD-8859 1776 DVD-0397 Apocalypse Now DVD-3440 1900 DVD-4443 DVD-6825 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 Army of Shadows DVD-3022 9th Company DVD-1383 Ashes and Diamonds DVD-3642 Act of Killing DVD-4434 Auschwitz Death Camp DVD-8792 Adams Chronicles DVD-3572 Auschwitz: Inside the Nazi State DVD-7615 Aftermath: The Remnants of War DVD-5233 Bad Voodoo's War DVD-1254 Against the Odds: Resistance in Nazi Concentration DVD-0592 Baghdad ER DVD-2538 Camps Age of Anxiety VHS-4359 Ballad of a Soldier DVD-1330 Al Qaeda Files DVD-5382 Band of Brothers (Discs 1-4) c.2 DVD-0580 Discs Alexander DVD-5380 Band of Brothers (Discs 5-6) c.2 DVD-0580 Discs Alive Day Memories: Home from Iraq DVD-6536 Bataan/Back to Bataan DVD-1645 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD-0238 Battle of Algiers DVD-0826 DVD-1284 Battle of Algiers c.4 DVD-0826 c.4 America Goes to War: World War II DVD-8059 Battle of Algiers c.3 DVD-0826 c.3 American Humanitarian Effort: Out-Takes from Vietnam DVD-8130 Battleground DVD-9109 American Sniper DVD-8997 Bedford Incident DVD-6742 DVD-8328 Beirut Diaries and 33 Days DVD-5080 Americanization of Emily DVD-1501 Beowulf DVD-3570 Andre's Lives VHS-4725 Best Years of Our Lives DVD-5227 Anne Frank DVD-3303 Best Years of Our Lives c.3 DVD-5227 c.3 Anne Frank: The Life of a Young Girl DVD-3579 Beyond Treason: What You Don't Know About Your DVD-4903 Government Could Kill You 9/6/2018 Big Red One DVD-2680 Catch-22 DVD-3479 DVD-9115 Cell Next Door DVD-4578 Birth of a Nation DVD-0060 Charge of the Light Brigade (Flynn) DVD-2931 Birth of a Nation and the Civil War Films of D.W. -

Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures

Social Education 76(1), pp 22–28 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies The Reel History of the World: Teaching World History with Major Motion Pictures William Benedict Russell III n today’s society, film is a part of popular culture and is relevant to students’ as well as an explanation as to why the everyday lives. Most students spend over 7 hours a day using media (over 50 class will view the film. Ihours a week).1 Nearly 50 percent of students’ media use per day is devoted to Watching the Film. When students videos (film) and television. With the popularity and availability of film, it is natural are watching the film (in its entirety that teachers attempt to engage students with such a relevant medium. In fact, in or selected clips), ensure that they are a recent study of social studies teachers, 100 percent reported using film at least aware of what they should be paying once a month to help teach content.2 In a national study of 327 teachers, 69 percent particular attention to. Pause the film reported that they use some type of film/movie to help teach Holocaust content. to pose a question, provide background, The method of using film and the method of using firsthand accounts were tied for or make a connection with an earlier les- the number one method teachers use to teach Holocaust content.3 Furthermore, a son. Interrupting a showing (at least once) national survey of social studies teachers conducted in 2006, found that 63 percent subtly reminds students that the purpose of eighth-grade teachers reported using some type of video-based activity in the of this classroom activity is not entertain- last social studies class they taught.4 ment, but critical thinking. -

Letters from Japanese General

Witness to Valor Charles (Chuck) Tatum 1 16 General Tadamichi Kuribayashi was the Japanese Commanding officer of the Japanese Garrison on Iwo Jima. The following are letters from the Japanese Commanding General of Iwo Jima during the invasion by U.S. Forces. These letters are a continuation of the article started in the 13 September issue of the Suribachi Sentinel. Letter to wife: 19 November 1944. I’m still feeling fine so don’t worry about me. Even on Iwo Jima it has cooled off but the flies still bother us. It must be cold in Tokyo so be careful not to catch cold. I know from listening to the radio that you have been hearing the air raid sirens. It won’t be long before you will be experiencing the real thing. Be prepared for them. I wrote detailed instructions to you in another letter and as an officer is flying to Tokyo, I will have him take this letter. I am sending one package of cake with him. Very Truly Yours, Tadamichi 27 November 1944 (To Taro) Witness to Valor Charles (Chuck) Tatum 2 16 My dear Taro: According to your mother’s letters you have been studying and working at the supply depot very hard. I was glad to hear that. I, your father, stand on Iwo Jima, the island which will soon be attacked by the American forces. In other words this island is the gateway to Japan. My heart is as strong as that of General M. Kusunoke who gave his life for Japan 650 years ago at the Minato River.