IAFOR Journal of Literature & Librarianship – Volume 9 – Issie 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hrudní Endovaskulární Graft Zenith Alpha™ Návod K Použití

MEDICAL EN Zenith Alpha™ Thoracic Endovascular Graft 15 Instructions for Use CS Hrudní endovaskulární graft Zenith Alpha™ 22 Návod k použití DA Zenith Alpha™ torakal endovaskulær protese 29 Brugsanvisning DE Zenith Alpha™ thorakale endovaskuläre Prothese 36 Gebrauchsanweisung EL Θωρακικό ενδαγγειακό μόσχευμα Zenith Alpha™ 44 Οδηγίες χρήσης ES Endoprótesis vascular torácica Zenith Alpha™ 52 Instrucciones de uso FR Endoprothèse vasculaire thoracique Zenith Alpha™ 60 Mode d’emploi HU Zenith Alpha™ mellkasi endovaszkuláris graft 67 Használati utasítás IT Protesi endovascolare toracica Zenith Alpha™ 74 Istruzioni per l’uso NL Zenith Alpha™ thoracale endovasculaire prothese 81 Gebruiksaanwijzing NO Zenith Alpha™ torakalt endovaskulært implantat 88 Bruksanvisning PL Piersiowy stent-graft wewnątrznaczyniowy Zenith Alpha™ 95 Instrukcja użycia PT Prótese endovascular torácica Zenith Alpha™ 103 Instruções de utilização SV Zenith Alpha™ endovaskulärt graft för thorax 110 Bruksanvisning Patient I.D. Card Included I-ALPHA-TAA-1306-436-01 *436-01* ENGLISH ČESKY TABLE OF COntents OBSAH 1 DEVICE DESCRIPTION ....................................................................... 15 1 POPIS ZAŘÍZENÍ ....................................................................................... 22 1.1 Zenith Alpha Thoracic Endovascular Graft .........................................15 1.1 Hrudní endovaskulární graft Zenith Alpha .............................................. 22 1.2 Introduction System ...................................................................................15 -

Ballad of the Buried Life

Ballad of the Buried Life From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Ballad of the Buried Life rudolf hagelstange translated by herman salinger with an introduction by charles w. hoffman UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 38 Copyright © 1962 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Hagelstange, Rudolf. Ballad of the Buried Life. Translated by Herman Salinger. Chapel Hill: University of North Car- olina Press, 1962. doi: https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469658285_Hagel- stange Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Salinger, Herman. Title: Ballad of the buried life / by Herman Salinger. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 38. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1962] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. Identifiers: lccn unk81010792 | isbn 978-0-8078-8038-8 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5828-5 (ebook) Classification: lcc pd25 .n6 no. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography by the late F. Seymour-Smith Reference books and other standard sources of literary information; with a selection of national historical and critical surveys, excluding monographs on individual authors (other than series) and anthologies. Imprint: the place of publication other than London is stated, followed by the date of the last edition traced up to 1984. OUP- Oxford University Press, and includes depart mental Oxford imprints such as Clarendon Press and the London OUP. But Oxford books originating outside Britain, e.g. Australia, New York, are so indicated. CUP - Cambridge University Press. General and European (An enlarged and updated edition of Lexicon tkr WeltliU!-atur im 20 ]ahrhuntkrt. Infra.), rev. 1981. Baker, Ernest A: A Guilk to the B6st Fiction. Ford, Ford Madox: The March of LiU!-ature. Routledge, 1932, rev. 1940. Allen and Unwin, 1939. Beer, Johannes: Dn Romanfohrn. 14 vols. Frauwallner, E. and others (eds): Die Welt Stuttgart, Anton Hiersemann, 1950-69. LiU!-alur. 3 vols. Vienna, 1951-4. Supplement Benet, William Rose: The R6athr's Encyc/opludia. (A· F), 1968. Harrap, 1955. Freedman, Ralph: The Lyrical Novel: studies in Bompiani, Valentino: Di.cionario letU!-ario Hnmann Hesse, Andrl Gilk and Virginia Woolf Bompiani dille opn-e 6 tUi personaggi di tutti i Princeton; OUP, 1963. tnnpi 6 di tutu le let16ratur6. 9 vols (including Grigson, Geoffrey (ed.): The Concise Encyclopadia index vol.). Milan, Bompiani, 1947-50. Ap of Motkm World LiU!-ature. Hutchinson, 1970. pendic6. 2 vols. 1964-6. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, W .N .: Everyman's Dic Chambn's Biographical Dictionary. Chambers, tionary of European WriU!-s. -

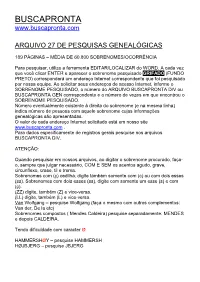

Adams Adkinson Aeschlimann Aisslinger Akkermann

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 27 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 189 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 60.800 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Between Music

Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress 7 Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Of Essence and Context Between Music and Philosophy Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress Volume 7 Series Editor Dario Martinelli, Faculty of Creative Industries, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Vilnius, Lithuania [email protected] The series originates from the need to create a more proactive platform in the form of monographs and edited volumes in thematic collections, to discuss the current crisis of the humanities and its possible solutions, in a spirit that should be both critical and self-critical. “Numanities” (New Humanities) aim to unify the various approaches and potentials of the humanities in the context, dynamics and problems of current societies, and in the attempt to overcome the crisis. The series is intended to target an academic audience interested in the following areas: – Traditional fields of humanities whose research paths are focused on issues of current concern; – New fields of humanities emerged to meet the demands of societal changes; – Multi/Inter/Cross/Transdisciplinary dialogues between humanities and social and/or natural sciences; – Humanities “in disguise”, that is, those fields (currently belonging to other spheres), that remain rooted in a humanistic vision of the world; – Forms of investigations and reflections, in which the humanities monitor and critically assess their scientific status and social condition; – Forms of research animated by creative and innovative humanities-based -

Hotel: Vuote Metà Delle Camere PAGANO PIERLUIGI GHIGGINI

DA SABATO 11 AGOSTO A VENERDÌ 17 AGOSTO 2012 *Abbinamento obbligatorio in edicola con “Il Giornale” al prezzo complessivo di Euro 1,20 ANNO XI NUMERO 63 • € 1,20 Spedizione in abbonamento postale - D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n. 46), art. 1, comma 1 - CN/RE IDOVE ANDAREI IALBINEAI ILA RUBRICAI IQUI BRUXELLESI Tutte le feste Un milione di € Conosci chi Auto più sicure di Ferragosto per riscoprire ti governa: per salvare in montagna i borghi rurali Rita Moriconi 1.200 vite l’anno A PAGINA 15 ALLE PAGIN E 18 E 19 A PAGINA 13 A PAGINA 11 INCHIESTA L’Osservatorio di Confcommercio sulle presenze nei primi mesi del 2012 Editoriale CRAC CMR I DEBITI SI Hotel: vuote metà delle camere PAGANO PIERLUIGI GHIGGINI Il turismo di affari, principale introito per la nostra città, ha subito un tracollo ON si può restare indifferenti di fronte Nai guai di Reggiolo. REGGIO – Tracollo degli alber- Prima il crac Cmr con i soci ghi: metà delle camere sono risparmiatori ingannati senza vuote. E’ quanto rivela l’Osser- ritegno, poi il terremoto, infi- vatorio di Confcommercio su un ne la notizia che il rimborso campione di albergatori, che del 90% del prestito sociale hanno fornito le presenze nei era solo una pia illusione. Se primi mesi del 2012: rispetto va bene i soci rivedranno il allo stesso periodo del 2011 si è 67% in sei anni: su 49 milio- registrato -47% nei 4 stelle e - ni versati con una fiducia 56% nei 3 stelle. «Siamo a livelli cieca nella gestione della di sussistenza, si può solo resi- cooperativa, ne perderanno stere», dice Francesca Lombar- almeno 16, e strada facendo dini, presidente Astoria. -

Sunday Morning, March 31

SUNDAY MORNING, MARCH 31 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (N) (cc) Easter Worship at the United Meth- This Week With George Stepha- Your Voice, Your Paid 2/KATU 2 2 odist Church nopoulos (N) (cc) (TVG) Vote CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation (N) (cc) ATP Tennis Sony Open, Men’s Final. (N) (Live) (cc) 2013 NCAA Basketball Tournament 6/KOIN 6 6 Regional Final. NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) (TVG) NHL Hockey Chicago at Detroit Red Wings. (N) (Live) (cc) 8/KGW 8 8 Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Daniel Tiger’s Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature River of No Return. Frank Oregon Experience Modoc War. 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge Church River of No Return. (TVG) (TVG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) Paid Paid Paid Paid Wicker Park ★★ (‘04) Josh Hart- 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) nett, Rose Byrne. ‘PG-13’ (1:54) Paid Paid David Jeremiah Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Life Change Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Kingdom Con- David Jeremiah Praise W/Kenneth Winning Walk (cc) A Miracle For You Redemption (cc) Love Worth Find- In Touch (cc) PowerPoint With It Is Written (cc) Answers With Time for a 24/KNMT 20 20 nection (cc) Hagin (TVG) (cc) (TVG) ing (TVG) (TVPG) Jack Graham. -

LIONEL TENNYSON S^ LIONEL TENNYSON

UC-NRLF B 3 Mb2 TflS K^^-. 1^^^^.1/ •^Mk }^iMl''P(y 1 1 JfyAXd U '(^ li^^M UNfVERSlTY'OF CALIFORNIA tC I'W w ,ch f^ji LIONEL TENNYSON s^ LIONEL TENNYSON Truth, for Truth is Truth, he worshlpt, being true as he was brave, Good, for Good is Good, he follow'd, yet he look'd beyond the grave." T. PRIVATELY PRIXTED IL u ti n MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 189I 7 he Risht of J'ransiaiion and Reproduction is Reset ved 5^^^'IU^ Richard Clay and Sons, Limited, london and bungay. ThsAs MAih] CONTENTS PAGE Memorial Tablet vii Memoir ix Diary in India i Two Articles from the "Cornhill"— {a) My Baby or My Dog 49 {b) Plea for Musicians 66 Article from the " Daily News " 85 "— Two Articles from the " Nineteenth Century {a) Ph.^DRA and PHfeDRE. JANUARY 1880 88 {b) Persia and its Passion Drama. April iSSi . 127 Poems ^77 Translation by Hallam Tennyson i93 Press Notices ^^^ 430 ON THE CENOTAPH IN FRESHWATER CHURCH 5n /IDemoriam LIONEL TENNYSON FILII, MARITI, FRATRIS CARISSIMI, FORMA, MENTE, MORUM SIMPLICITATE, LAUDEM INTER AEQUALES MATURE ADEPTI, FAMAM QUOQUE IN REPUBLICA, SI VITA SUFFECISSET, SINE DUBIO ADEPTURI. OBDORMIVIT IN CHRISTO DIE APR: XX. ANNO CHRISTI MDCCCLXXXVI. ^TAT. XXXII. ET IN MARI APUD PERIM INDORUM SEPULTUS EST. MEMOIR Lionel Tennyson was born on March i6th 1854, at Farringford, in the Isle of Wight. From his babyhood he was always an affectionate, joyous, and beautiful child. As he developed, he was imagi- native, and very fond of music, and of fairy stories, legends, and old ballads, read at his mother's knee. -

Waiting Is the Hardest Part

University Archives (02) Campus Box 1063 News .... Opinion . A&E.......... Sports . A new spin on vinyl Puzzles....................15 page 6 Classifieds...............16 Alton - East St. Louis - Edwardsville Thursday, April 14, 2011 www.alestlelive.com Vol. 63, No. 27 Waiting is the hardest part Greek housing over budget again, delayed for at least a year KARI WILLIAMS Alestle Opinion Editor CC Greek housing has been put It’s disheartening because I’ve been working on hold for a second time because of over budgeting. on it for almost two years and now and I Junior political science major - Nic Simpson, who serves as Alpha won’t even be able to see it come through... Kappa Lambda vice president and -Nic Simpson housing chair, said Greek housing Alpha Kappa Lambda vice president is on hold because, with the budget being 20 percent over, it has to be reapproved by the Board and time constraints. five in second.” o f Trustees and Illinois Board of Greek housing is required to According to Schultz, the Higher Education. have sprinkler systems installed by committee estimated that taking “I am kind o f in shock that it state law, and Schultz said the care o f asbestos would cost about happened again,” Simpson said. water pipe sizes coming into the $150,000, and it came in around “It’s disheartening because I’ve building would have to be $930,000. With air testing, that been working on it for almost two increased. amount was about $1 million. In compliance with the Senior business and financial years and now and I won’t even Alestle file graphic be able to see it come through if Americans with Disabilities Act, management major Zac Sandefer the sidewalks would have to be of Charleston, a member of the Beginning with a $7.5 million budget, the Cougar Village it does come through.” renovations for Greek housing came in 20 percent more than This time the budget came in updated, which they were not Greek housing committee, said expected. -

RML Spring 2021 Rights Guide

NON-FICTION TO STAND AND STARE: How To Garden While Doing Next to Nothing Andrew Timothy O’Brien There’s a lot of advice out there that would tell you how to do numerous things in your garden. But not so much that invites you to think about how to be while you’re out there. With increasingly busy lives, yet another list of chores seems like the very last thing any of us needs when it comes to our own practice of self-care, relaxation and renewal. After all, aren’t these the things we wanted to escape to the garden for in the first place? Put aside the ‘Jobs to do this week’ section in the Sunday papers. What if there were a more low-intervention way to On submission Spring 2021 garden, some reciprocal arrangement through which both you and your soil get fed, with the minimum degree of fuss, effort and guilt on your part, and the maximum measure of healthy, organic growth on that of your garden? In To Stand and Stare, Andrew Timothy O’Brien weaves together strands of botany, philosophy and mindfulness to form an ecological narrative suffused with practical gardening know-how. Informed by a deep understanding and appreciation of natural processes, O’Brien encourages the reader to think from the ground up, as we follow the pattern of a plant’s growth through the season – roots, shoots, and fruits – while advocating an increased awareness of our surroundings. ANDREW TIMOTHY O’BRIEN is an online gardening coach, blogger and host of the critically acclaimed Gardens, Weeds & Words podcast. -

Philip M. Kelly

Kendall Brill & Klieger LLP 10100 Santa Monica Blvd Suite 1725 Los Angeles, California 90067 310.556.2700 telephone 310.556.2705 facsimile www.kbkfirm.com Philip M. Kelly Partner Education 310.272.7908 University of California, Los Angeles School of Law, J.D., pkelly@kbkfirm.com 2000 Order of the Coif Pomona College, B.A., Economics, 1995 Athletic Hall of Fame, Men’s Basketball Philip Kelly focuses on successfully resolving entertainment and commercial litigation disputes. He counsels and advises leading motion picture studios, broadcast and cable television networks, entertainment production, sporting and music companies, book publishers, technology leaders, and video-game publishers. Legal challenges involving profit participation, licensing, copyrights, distribution agreements, fraud, and breach of contract claims are among the legal matters that Mr. Kelly regularly manages. Currently, Mr. Kelly is litigating high- visibility libel and slander claims for an athlete and defending a breach of contract action related to a best-selling book. In addition to his litigation representation across a variety of entertainment and media platforms, Mr. Kelly provides pre-broadcast counseling and advice to production companies and television networks. Representative Matters Media, Entertainment, and Intellectual Property Libel and Slander Litigation Represented Universal Music Group before the California Supreme Court in a landmark case involving the scope of Representing British soccer player David Beckham in libel attorney-client privilege. Then, Mr. Kelly “second chaired” and slander litigation against prominent magazine. the client’s subsequent trial victory. Entertainment Industry Disputes Litigated on behalf of a major studio and its broadcast network in a $100 million breach of contract dispute with Represent Screen Media Ventures in litigation with its largest affiliate group. -

A Theological Reading of Selected Works of Matthew

THE POETICS OF LOSS: A THEOLOGICAL READING OF SELECTED WORKS OF MATTHEW ARNOLD Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Theological Studies By Anthony Nicholas De Santis, B.A. Dayton, Ohio August 2020 THE POETICS OF LOSS: A THEOLOGICAL READING OF SELECTED WORKS OF MATTHEW ARNOLD Name: De Santis, Anthony Nicholas APPROVED BY: _____________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Chair _____________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________ Mark Ryan, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _____________________________________ Daniel Speed Thompson, Ph.D. Department Chairperson ii © Copyright by Anthony Nicholas De Santis All rights reserved 2020 iii ABSTRACT THE POETICS OF LOSS: A THEOLOGICAL READING OF SELECTED WORKS OF MATTHEW ARNOLD Name: De Santis, Anthony Nicholas University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier The Poetics of Loss: A Theological Reading of Selected Works of Matthew Arnold is one Catholic theologian’s attempt to make sense of the mysterious, and possibly troubling, claim that Arnold is “a serious theological thinker.”1 If the author finds this claim mysterious, it is not least because Arnold’s poetry engages and relies on a ‘poetics of loss,’ which the author defines as Arnold’s felt sense of isolation, disintegration, and hopelessness as he observes the Sea of Faith retreating.2 Despite what must be to the Catholic theologian Arnold’s troubling and troubled existential, religious, and socio- historical commitments, however, the author argues that Arnold’s poetry is precisely where Arnold is most theologically significant, relevant, and compelling.