Obama's Chief of Staff Will Be the Most Important Appointment of His

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Update 444 N

National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers and Treasurers WASHINGTON UPDATE 444 N. Capitol Street NW, Suite 234 Washington, DC 20001 March 11, 2013 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President President Names New OMB Director issues for the MSRB. Suggested priorities MARTIN J. BENISON or initiatives should relate to any of the Comptroller Massachusetts President Barack Obama has nominated MSRB’s core activities: Sylvia Mathews Burwell, president of the First Vice President Regulating municipal securities dealers JAMES B. LEWIS Walmart Foundation, as the next director of State Treasurer the U.S. Office of Management and Budg- and municipal advisors. New Mexico et. She will take over for Jeffrey Zients, Operating market transparency sys- tems. Second Vice President who was named acting director of OMB in WILLIAM .G HOLLAND January 2012. Burwell previously worked Providing education, outreach and mar- Auditor General in the budget office as deputy director from ket leadership. Illinois 1998 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton, Secretary and she served as deputy chief of staff un- When providing feedback, the MSRB en- CALVIN McKELVOGUE der Jack Lew. Lew was confirmed as treas- courages commenters to be as specific as Chief Operating Officer possible and provide as much information State Accounting Enterprise ury secretary by the Senate two weeks ago. Iowa as possible about particular issues and top- Nunes to Resurrect Bill to Block Bond ics. In addition to providing the MSRB Treasurer with specific concerns about regulatory and RICHARD K. ELLIS Sales Without Pension Disclosure State Treasurer market transparency issues, the MSRB en- Utah Office of the State Treasurer Rep. Devin Nunes (R-CA) has indicated his courages commenters to provide input on its education, outreach and market leader- Immediate Past President intention to reintroduce his “Public Em- RONALD L. -

US Policy Scan 2021

US Policy Scan 2021 1 • US Policy Scan 2021 Introduction Welcome to Dentons 2021 Policy Scan, an in-depth look at policy a number of Members of Congress and Senators on both sides of at the Federal level and in each of the 50 states. This document the aisle and with a public exhausted by the anger and overheated is meant to be both a resource and a guide. A preview of the rhetoric that has characterized the last four years. key policy questions for the next year in the states, the House of Representatives, the Senate and the new Administration. A Nonetheless, with a Congress closely divided between the parties resource for tracking the people who will be driving change. and many millions of people who even now question the basic legitimacy of the process that led to Biden’s election, it remains to In addition to a dive into more than 15 policy areas, you will find be determined whether the President-elect’s goals are achievable brief profiles of Biden cabinet nominees and senior White House or whether, going forward, the Trump years have fundamentally staff appointees, the Congressional calendar, as well as the and permanently altered the manner in which political discourse Session dates and policy previews in State Houses across the will be conducted. What we can say with total confidence is that, in country. We discuss redistricting, preview the 2022 US Senate such a politically charged environment, it will take tremendous skill races and provide an overview of key decided and pending cases and determination on the part of the President-elect, along with a before the Supreme Court of the United States. -

President Biden Appeals for Unity He Faces a Confluence of Crises Stemming from Pandemic, Insurrection & Race by BRIAN A

V26, N21 Thursday, Jan.21, 2021 President Biden appeals for unity He faces a confluence of crises stemming from pandemic, insurrection & race By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – In what remains a crime scene from the insurrection on Jan. 6, President Joe Biden took the oath of office at the U.S. Capitol Wednesday, appealing to all Americans for “unity” and the survival of the planet’s oldest democ- racy. “We’ve learned again that democracy is precious,” when he declared in strongman fashion, “I alone can fix Biden said shortly before noon Wednesday after taking the it.” oath of office from Chief Justice John Roberts. “Democ- When Trump fitfully turned the reins over to Biden racy is fragile. And at this hour, my friends, democracy has without ever acknowledging the latter’s victory, it came prevailed.” after the Capitol insurrection on Jan. 6 that Senate Minor- His words of assurance came four years to the day ity Leader Mitch McConnell said he had “provoked,” leading since President Trump delivered his dystopian “American to an unprecedented second impeachment. It came with carnage” address, coming on the heels of his Republican National Convention speech in Cleveland in July 2016 Continued on page 3 Biden’s critical challenge By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – Here is the most critical chal- lenge facing President Biden: Vaccinate as many of the 320 million Americans as soon as possible. While the Trump administration’s Operation Warp “Hoosiers have risen to meet Speed helped develop the CO- VID-19 vaccine in record time, these unprecedented challenges. most of the manufactured doses haven’t been injected into the The state of our state is resilient arms of Americans. -

OAKLAND COUNTY DIRECTORY 2016 Oakland County Directory Lisa Brown - Oakland County Clerk/Register of Deeds Experience Oakgov.Com/Clerkrod 2016

OAKLAND COUNTY DIRECTORY 2016 Oakland County Directory Lisa Brown - Oakland County Clerk/Register of Deeds Experience oakgov.com/clerkrod 2016 Get Fit! Seven parks offer natural and paved trails for hiking, biking and equestrians. From Farm to Family Oakland County Market offers grower-direct fresh produce and flowers year-round from more than 140 farmers and artisans representing 17 Michigan counties. Get Outdoors Cool Off Camp Learn to golf at five courses! Season Passes for two waterparks. With Family and friends. Visit DestinationOakland.com About the Front Cover An art contest was held by Oakland County Clerk/Register of Deeds Lisa Brown that was open to all high school students who live and attend school in Oakland County. Students made original works of art depicting the theme of “The Importance of Voting.” The winning art piece, shown on the cover, was created by Kate Donoghue of Sylvan Lake. “Through my picture, I tried to portray that if you have the ability to vote but do not take the opportunity to do it, your thoughts and opinions will never be represented,” said Kate. She added, “I think that it is very important to vote if you have the chance to do so because your beliefs and the decision making ability of others could determine your future.” Kate used Sharpies and watercolor pencils to create her artwork. Congratulations, Kate! Lisa Brown OAKLAAND COUNTY CLERK/REGISTER OF DEEDS www.oakgov.com/clerkrod Dear Oakland County County Resident: Resident: II’m'm honoredhonored toto serveserve as as your your Clerk/Register Clerk/Register of ofDeeds. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

Gibson Dunn Webcast: New Congress and New Administration

New Congress and New Administration: A Different Legislative and Policy Landscape for Companies January 22, 2021 Agenda 1. Congressional Landscape 2. Administration’s New Landscape 3. Financial Services 4. Antitrust 5. Consumer Protection/Privacy 6. Questions 2 LAY OF THE LAND IN THE 117TH CONGRESS (SENATE) Health, Education, Commerce, Science Homeland Security Armed Services & Gov. Affairs Labor & Pensions & Transportation Gary Peters Rob Portman Patty Murray Richard Burr Jack Reed Jim Inhofe Maria Cantwell Roger Wicker (D-MI) (R-OH) (D-WA) (R-NC) (D-RI) (R-OK) (D-WA) (R-MS) Judiciary Finance Banking, Housing & Urban Affairs Aging Dick Durbin Charles Grassley Ron Wyden Mike Crapo Sherrod Brown Pat Toomey Bob Casey Tim Scott (D-IL) (R-IA) (D-OR) (R-ID) (D-OH) (R-PA) (D-PA) (R-SC) Agriculture Appropriations Budget Foreign Affairs Debbie Stabenow John Boozman Patrick Leahy Richard Shelby Bernie Sanders Lindsay Graham Bob Menendez James Risch (D-MI) (R-AR) (D-VT) (R-AL) (I-VT) (R-SC) (D-NJ) (R-ID) 3 PRIVILEGED AND CONFIDENTIAL – ATTORNEY WORK PRODUCT LAY OF THE LAND IN THE 117TH CONGRESS (HOUSE) Labor & Education Transportation Appropriations Energy & Commerce Financial Services Bobby Scott Virginia Foxx Peter DeFazio Sam Graves Rosa DeLaura Kay Granger Frank Pallone Cathy Maxine Waters Patrick McHenry (D-VA) (R-NC) (D-OR) (R-MO) (D-CT) (R-TX) (D-NJ) McMorris (D-CA) (R-NC) Rodgers (R-WA) Oversight & Science, Space Government Reform Homeland Security Judiciary Ways & Means & Technology Carolyn James Comer Bennie Mike Rogers Jerrold Jim Jordan Richard Neal Kevin Brady Eddie Bernice Frank Lucas Maloney (R-KY) Thompson (R-AL) Nadler (R-OH) (D-MA) (R-TX) Johnson (R-OK) (D-NY) (D-MS) (D-NY) (D-TX) 4 PRIVILEGED AND CONFIDENTIAL – ATTORNEY WORK PRODUCT The Senate Confirmation Process • Nominees are subject to lengthy questionnaires from the Senate Committee in charge of their nomination as well as FBI background checks. -

Statement on Procedural Rule Changes in the Senate Remarks On

Administration of Barack Obama, 2013 / Jan. 25 enhance our readiness, and be another step to- don’t tell”—the professionalism of our Armed ward fulfilling our Nation’s founding ideals of Forces will ensure a smooth transition and fairness and equality. I congratulate our mili- keep our military the very best in the world. tary, including the Joint Chiefs of Staff, for the Today every American can be proud that our rigor that they have brought to this process. As military will grow even stronger with our moth- Commander in Chief, I am absolutely confi- ers, wives, sisters, and daughters playing a dent that—as with the repeal of “don’t ask, greater role in protecting this country we love. Statement on Procedural Rule Changes in the Senate January 24, 2013 In my State of the Union last year, I urged pave the way for the Senate to take meaningful Congress to take steps to fix the way they do action in the days and weeks ahead. business. Specifically, I asked them to address I also want to thank leaders in Congress for the fact that a simple majority is no longer changing the Senate rules in an effort to resur- enough to pass anything—even routine busi- rect the longstanding tradition of considering ness—through the Senate. And today I am consensus district court judicial nominations pleased that a bipartisan group of Senators has on a more routine basis. After being approved agreed to take action. by the Senate Judiciary Committee, my judi- Too often over the past 4 years, a single Sen- cial nominees have waited more than three ator or a handful of Senators has been able to times longer to receive confirmation votes than unilaterally block or delay bipartisan legislation those of my predecessor, even though the for the sole purpose of making a political point. -

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks on Signing The

Administration of Barack H. Obama, 2010 Remarks on Signing the Improper Payments Elimination and Recovery Act of 2010 July 22, 2010 Morning, everybody. Thank you. Thank you. Everybody, please have a seat. Welcome to the White House. I am pleased that you could all join us today as I sign this bill, the Improper Payments Elimination and Recovery Act, which, translated into English, means cutting down on waste, fraud, and abuse and ensuring that our Government serves as a responsible steward for the tax dollars of the American people. Now, this is a responsibility we've been working to fulfill from the very beginning of this administration. Back when I first started campaigning for office, I said I wanted to change the way Washington works so that it works for the American people. I meant making Government more open and more transparent and more responsive to the needs of the people. I meant getting rid of the waste and inefficiencies that squander the people's hard-earned money. And I meant finally revamping the systems that undermine our efficiency and threaten our security and fail to serve the interests of the American people. Now, there are outstanding public servants doing essential work throughout our Government. But too often, their best efforts are thwarted by outdated technologies and outmoded ways of doing business. That needs to change. We have to challenge a status quo that accepts billions of dollars in waste as the cost of doing business and enables obsolete or underperforming programs to survive year after year simply because that's the way things have always been done. -

President Clinton From

Office of WILLIAM JEFFERSON CLINTON MEMORANDUM TO: PRESIDENT CLINTON FROM: MARC DUNKELMAN and TOM FREEDMAN CC: BRUCE LINDSEY DOUG BAND JUSTIN COOPER LAURA GRAHAM STEPHANIE STREETT JOHN PODESTA VALERIE ALEXANDER GREG MILNE RE: BOOK OF ESSAYS on THE CLINTON ADMINISTRATION Date: June 2012 Mr. President, In the spirit of the book of essays we produced for the reunion in Little Rock (“Turning Point”), we propose to commission a book of essays, written by your former staff, advisors, and those you worked with in the Congress, covering the broad spectrum issues you tackled during your presidency. We have not yet spoken to publishers, but have found that alums of your administration are eager to help document your contribution (and theirs). A book of roughly thirty 2,000 word essays would mark an opportunity to frame the various achievements of your eight years in the White House for historians in generations to come. Each essay would describe a challenge you faced in office, your philosophical approach, how your agenda proceeded through your tenure in office, and the results. You could pen the introduction. Handled properly, we would likely be 1 able to get some of the stories embedded in the essays to the press before and during publication. Would you look to proceed with this proposal? ___YES ___NO ___DISCUSS If you are interested in moving forward, here is a preliminary list of subjects and authors. We could begin speaking with publishers, and begin approaching the alumni who would write the articles. Broadly, we have broken the subjects into four categories: Economics, Domestic Policy, Foreign Policy, and Governing Philosophy. -

Biden: NARKIVE, “They Will Palestine in Violation of 11

Will the ETHNIC FACTOR in Biden's KEY cabinet members preclude again (as it did with Trump’s KEY cabinet members) bringing home some 70,000 U.S. troops whose deployment for Israel’s security and prosperity in the Middle East cost some $8 trillion and millions of people killed or displaced in that region? Biden's top Jewish picks met well a minyan and a half These disproportionate ethno- Trump: U.S. troops will remain in the Middle East for Israel, political appointments or 1. White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain The Washington Post, 11/28/2018, https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Trump-US-troops-will-remain-in-the-Middle-East-for-Israel-572997 2. Secretary of State Antony Blinken nominations by both Biden and 3. Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen Trump in addition to dozens of Iraq Was Invaded 'to Protect Israel' , https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1475-4967.2006.00260.x elected Jewish Members of 4. US Ambassador to Israel Tom Nides Remember: The "ardent faith" of the war in Iraq was conceived and 5. Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas Congress can only give a disseminated by a small group of 25 or 30 neoconservatives, almost all of 6. Member of Council of Economic Advisers Jared Bernstein glimpse of the Power of Israel in them Jewish, almost all of them intellectuals (a partial list: Richard Perle, Paul 7. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry/Cohen the United States and the depth Wolfowitz, Douglas Feith, William Kristol, Eliot Abrams, Charles 8. -

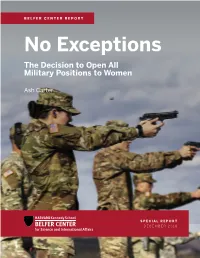

No Exceptions: the Decision to Open All Military Positions to Women Table of Contents

BELFER CENTER REPORT No Exceptions The Decision to Open All Military Positions to Women Ash Carter SPECIAL REPORT DECEMBER 2018 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the author and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: KFOR Multinational Battle Group-East Soldiers fire the M9 pistol from the firing line during the weapons qualification event for the German Armed Forces Proficiency Badge at Camp Bondsteel, Kosovo, Dec. 12, 2017. (U.S. Army Photo / Staff Sgt. Nicholas Farina) Copyright 2018, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America BELFER CENTER REPORT No Exceptions The Decision to Open All Military Positions to Women Ash Carter SPECIAL REPORT DECEMBER 2018 About the Author Ash Carter is a former United States Secretary of Defense and the current Director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Har- vard Kennedy School, where he leads the Technology and Public Purpose project. He is also an Innovation Fellow and corporation member at MIT. For over 35 years, Secretary Carter has leveraged his experience in national security, technology, and innovation to defend the United States and make a better world. He has done so under presidents of both political parties as well as in the private sector. As Secretary of Defense from 2015 to 2017, he pushed the Pentagon to “think outside its five-sided box.” He changed the trajectory of the mili- tary campaign to deliver ISIS a lasting defeat, designed and executed the strategic pivot to the Asia-Pacific, established a new playbook for the U.S. -

Election Insight 2020

ELECTION INSIGHT 2020 “This isn’t about – yeah, it is about me, I guess, when you think about it.” – President Donald J. Trump Kenosha Wisconsin Regional Airport Election Eve. 1 • Election Insight 2020 Contents 04 … Election Results on One Page 06 … Biden Transition Team 10 … Potential Biden Administration 2 • Election Insight 2020 Election Results on One Page 3 • Election Insight 2020 DENTONS’ DEMOCRATS Election Results on One Page “The waiting is the hardest part.” Election results as of 1:15 pm November 11th – Tom Petty Top Line Biden declared by multiple news networks to be America’s next president. Biden’s Pennsylvania win puts him over 270. Georgia and North Carolina not yet called. Biden narrowly leads in GA while Trump leads in NC. Trump campaign seeks recounts in GA and Wisconsin and files multiple lawsuits seeking to overturn the election results in states where Biden has won. Two January 5, 2021 runoff elections in Georgia will determine Senate control. Senator Mitch McConnell will remain Majority Leader and divided government will continue, complicating the prospects for Biden’s legislative agenda, unless Democrats win both runoff s. Democrats retain their House majority but Republicans narrow the Democrats’ margin with a net pickup of six seats. Incumbents Losing Reelection • Sen. Doug Jones (D-AL) • Rep. Harley Rouda (D-CA-48) • Rep. Xochitl Torres Small (D-NM-3) • Sen. Martha McSally (R-AZ) • Rep. Debbie Mucarsel-Powell (D-FL-26) • Rep. Max Rose (D-NY-11) • Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO) • Rep. Donna Shalala (D-FL-27) • Rep. Kendra Horn (D-OK-5) • Rep.