Fontaine Lien

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Brom Ebook

THE ART OF BROM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gerald Brom,John Fleskes,Arnie Fenner | 210 pages | 10 Oct 2013 | Flesk Publications | 9781933865492 | English | Santa Cruz, United States The Art of Brom PDF Book Sign up now. The Art Of Gerald Br Lynne Pickering ;Art and Interiors. Beach Art. Reward no longer available 1 backer. Log in Sign up. Your name will be listed in a special thank you page of the book. Skirt Drawing. Learn about new offers and get more deals by joining our newsletter. Rose Drawing Realistic. Accept all Manage Cookies. Includes an extra pages not found in the trade edition. This sumptuous coffee table book weaves together poetry, literature, culture, and art to illuminate the Brom Painting. Eucalyptus Leaves Drawing. Imagery from the Bird's Home: The Art of. Full color fine art representations throughout the large format volume. John Fleskes is the president and publisher of Flesk Publications. Product Details About the Author. Gerald Brom - Brom P Are you happy to accept all cookies? Mean Jellybean Brom Painting Of Womans Face. Bonnard World of Art. Caduceus Drawing. About the Author At age twenty, Brom began working full-time as a commercial illustrator in Atlanta, Georgia. He has since gone on to lend his distinctive vision to all facets of the creative industries, from novels and games, to comics and film. Brom has collected together the very best of his art spanning his 30 year career. Dispatched from the UK in 2 business days When will my order arrive? Also included is the 5. His head is constantly Art Of Brom - Brom P Free delivery worldwide. -

Qing Shi (The History of Love) in Late Ming Book Culture

Asiatische Studien Études Asiatiques LXVI · 4 · 2012 Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft Revue de la Société Suisse – Asie Aspects of Emotion in Late Imperial China Peter Lang Bern · Berlin · Bruxelles · Frankfurt am Main · New York · Oxford · Wien ISSN 0004-4717 © Peter Lang AG, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften, Bern 2012 Hochfeldstrasse 32, CH-3012 Bern [email protected], www.peterlang.com, www.peterlang.net Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschliesslich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ausserhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Printed in Hungary INHALTSVERZEICHNIS – TABLE DES MATIÈRES CONTENTS Nachruf – Nécrologie – Obituary JORRIT BRITSCHGI..............................................................................................................................877 Helmut Brinker (1939–2012) Thematic Section: Aspects of Emotion in Late Imperial China ANGELIKA C. MESSNER (ED.) ......................................................................................................893 Aspects of Emotion in Late Imperial China. Editor’s introduction to the thematic section BARBARA BISETTO ............................................................................................................................915 The Composition of Qing shi (The History of Love) -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

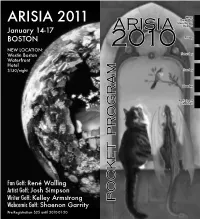

Arisia 2010 Pocket Program

Maps Quick Ref ARISIA 2011 Main Events Dealers January 14-17 ARISIA BOSTON 2010 Friday NEW LOCATION: Westin Boston Saturday Waterfront Hotel $130/night Sunday Monday Participant Schedules Fan GoH: RenŽ Walling Artist GoH: Josh Simpson Writer GoH: Kelley Armstrong POCKET PROGRAM Webcomic GoH: Shaenon Garrity Pre-Registration $25 until 2010-01-20 B 1st Floor Paul MAPS HOTEL Revere Garage A Main Program Ops Entrance Masquerade, Bone Marrow & Blood Drive President’s CD Gift Sign-ups Fan Tables Shop D Registration Crispus Attucks William Dawes Molly Pitcher Business Center A B Info Desk BC Elevators Arisia Sales Prefunction Thomas Paine Haym President’s B President’s A Solomon Coat Food Cart Check A Front Desk EscalatorsBathrooms Bridge to Garage/ Health Club 2nd Floor (stairs) 201 202 203 204 205 Rooms 207–223 Volunteer Lounge Bathrooms Elevators Aquarium Cambridge Rooms 212–224 Con Ops Atrium & Security Con Suite MAPSHOTEL Escalators Hotel Area Zephyr Patio No access Crow’s Nest: 3rd floor Atrium to Lobby Dealers’ Row: 3rd floor BU Lounge: 10th floor Zephyr Fast Track: Empress (14th floor) Rooms 237–256 Restaurant & Bar Art Show: Charles View (16th floor) QUICK REFERENCE QUICK REFERENCE Access/Handicapped Services go to Information Desk Filk (all night) Crispus Attucks Anime Room Haym Solomon Friday–Sunday 11pm–late Fri/Sat/Sun 7pm–6am Monday after teardown Arisia TV Channel 41 Films Molly Pitcher Movies, live ballroom events, etc. Friday 4pm–1am SciFi Channel replaces BBC channel for the con. Saturday 7pm–1am Art Show Charles View (16th floor) Sunday 6pm–1am Monday 9am–11am (audience choice vote 9am sharp) Friday 6pm–9pm Food Options Saturday 10am–8pm Sunday 10am–8pm Hotel Restaurant on second floor. -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Deconstructing Feminine and Feminist Fantastic Through the Study of Living Dolls

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 22 (2020) Issue 4 Article 7 Deconstructing Feminine and Feminist Fantastic through the Study of Living Dolls Raquel Velázquez University of Barcelona Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Spanish Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Velázquez, Raquel. "Deconstructing Feminine and Feminist Fantastic through the Study of Living Dolls." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 22.4 (2020): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.3720> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Fantastic Art Revisited: Exhibiting Old Masters & Contemporary Art

Fantastic Art Revisited: Exhibiting Old Masters & Contemporary Art A symposium presented by Nicholas Hall and Yuan Fang in conjunction with the exhibition at David Zwirner Endless Enigma: Eight Centuries of Fantastic Art Saturday Afternoon October 27, 2018 The Kitchen 512 W 19th Street, New York RSVP required for entry. Please email [email protected] or telephone +1 212-772-9100 Please arrive promptly as no one shall be seated once the presentation begins Fantastic Art Revisited: Exhibiting Old Masters and Contemporary Art is a symposium organized by Nicholas Hall and Yuan Fang, to take place on the closing day of the accompanying exhibition Endless Enigma: Eight Centuries of Fantastic Art at David Zwirner. The symposium brings into focus the legacy of Alfred H. Barr Jr.’s 1936 MoMA exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. A key point of reference for Endless Enigma, Barr’s exhibition brought art by Dada and Surrealist artists into the context of what he called ‘fantastic art’ by European Old Masters, whose works displayed unexpected thematic and formal relationships with those of the avant- garde. It was, in fact, one of the earliest modern museum exhibitions to explore the continuous conversation between art of the past and art of the present – a dialogue that has enjoyed increasing popularity in recent years across the museum and commercial art world. The half-day event will consist of presentations by curators and academics from leading European and American institutions. Divided into two sessions, the presentations will cover a diverse range of topics referencing a single work, subject or concept touched upon in Endless Enigma; the first session explores the earlier history of fantastic art, while the following session presents topics pertaining to museology and display. -

The University of Chicago Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology A

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRACTICES OF SCRIPTURAL ECONOMY: COMPILING AND COPYING A SEVENTH-CENTURY CHINESE BUDDHIST ANTHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVINITY SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ALEXANDER ONG HSU CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2018 © Copyright by Alexander Ong Hsu, 2018. All rights reserved. Dissertation Abstract: Practices of Scriptural Economy: Compiling and Copying a Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Anthology By Alexander Ong Hsu This dissertation reads a seventh-century Chinese Buddhist anthology to examine how medieval Chinese Buddhists practiced reducing and reorganizing their voluminous scriptural tra- dition into more useful formats. The anthology, A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma (Fayuan zhulin ), was compiled by a scholar-monk named Daoshi (?–683) from hundreds of Buddhist scriptures and other religious writings, listing thousands of quotations un- der a system of one-hundred category-chapters. This dissertation shows how A Grove of Pearls was designed by and for scriptural economy: it facilitated and was facilitated by traditions of categorizing, excerpting, and collecting units of scripture. Anthologies like A Grove of Pearls selectively copied the forms and contents of earlier Buddhist anthologies, catalogs, and other compilations; and, in turn, later Buddhists would selectively copy from it in order to spread the Buddhist dharma. I read anthologies not merely to describe their contents but to show what their compilers and copyists thought they were doing when they made and used them. A Grove of Pearls from the Garden of Dharma has often been read as an example of a Buddhist leishu , or “Chinese encyclopedia.” But the work’s precursors from the sixth cen- tury do not all fit neatly into this genre because they do not all use lei or categories consist- ently, nor do they all have encyclopedic breadth like A Grove of Pearls. -

Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 489 SO 025 360 AUTHOR Yu-ning, Li, Ed. TITLE Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM Johnson & Associates, 257 East South St., Franklin, IN 46131-2422 (paperback: $25; clothbound: ISBN-1-880938-008, $39; shipping: $3 first copy, $0.50 each additional copy). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chinese Culture; *Cultural Images; Females; Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Legends; Mythology; Role Perception; Sexism in Language; Sex Role; *Sex Stereotypes; Sexual Identity; *Womens Studies; World History; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Asian Culture; China; '`Chinese Literature ABSTRACT This book examines the ways in which Chinese literature offers a vast array of prospects, new interpretations, new fields of study, and new themes for the study of women. As a result of the global movement toward greater recognition of gender equality and human dignity, the study of women as portrayed in Chinese literature has a long and rich history. A single volume cannot cover the enormous field but offers volume is a starting point for further research. Several renowned Chinese writers and researchers contributed to the book. The volume includes the following: (1) Introduction (Li Yu- Wing);(2) Concepts of Redemption and Fall through Woman as Reflected in Chinese Literature (Tsung Su);(3) The Poems of Li Qingzhao (1084-1141) (Kai-yu Hsu); (4) Images of Women in Yuan Drama (Fan Pen Chen);(5) The Vanguards--The Truncated Stage (The Women of Lu Yin, Bing Xin, and Ding Ling) (Liu Nienling); (6) New Woman vs. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Discovering by Analysis: Harry Potter and Youth Fantasy

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 865 IR 058 417 AUTHOR Center, Emily R. TITLE Discovering by Analysis: Harry Potter and Youth Fantasy. PUB DATE 2001-08-00 NOTE 38p.; Master of Library and Information Science Research Paper, Kent State University. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Childrens Literature; *Fantasy; Fiction; Literary Criticism; *Reading Material Selection; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Harry Potter; *Reading Lists ABSTRACT There has been a recent surge in the popularity of youth fantasy books; this can be partially attributed to the popularity of J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series. Librarians and others who recommend books to youth are having a difficult time suggesting other fantasy books to those who have read the Harry Potter series and want to read other similar fantasy books, because they are not as familiar with the youth fantasy genre as with other genres. This study analyzed a list of youth fantasy books and compared them to the books in the Harry Potter series, through a breakdown of their fantasy elements (i.e., fantasy subgenres, main characters, secondary characters, plot elements, and miscellaneous elements) .Books chosen for the study were selected from lists of youth fantasy books recommended to fantasy readers and others that are currently in print. The study provides a resource for fantasy readers by quantifying the elements of the youth fantasy books, as well as creating a guide for those interested in the Harry Potter books. It also helps fill a gap in the research of youth fantasy. Appendices include a youth fantasy reading list, the coding sheet, data tables, and final annotated book list.(Contains 10 references and 9 tables.)(Author/MES) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Popular Fiction 1814-1939: Selections from the Anthony Tino Collection

POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION L.W. Currey, Inc. John W. Knott, Jr., Bookseller POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION WINTER - SPRING 2017 TERMS OF SALE & PAYMENT: ALL ITEMS subject to prior sale, reservations accepted, items held seven days pending payment or credit card details. Prices are net to all with the exception of booksellers with have previous reciprocal arrangements or are members of the ABAA/ILAB. (1). Checks and money orders drawn on U.S. banks in U.S. dollars. (2). Paypal (3). Credit Card: Mastercard, VISA and American Express. For credit cards please provide: (1) the name of the cardholder exactly as it appears on your card, (2) the billing address of your card, (3) your card number, (4) the expiration date of your card and (5) for MC and Visa the three digit code on the rear, for Amex the for digit code on the front. SALES TAX: Appropriate sales tax for NY and MD added. SHIPPING: Shipment cost additional on all orders. All shipments via U.S. Postal service. UNITED STATES: Priority mail, $12.00 first item, $8.00 each additional or Media mail (book rate) at $4.00 for the first item, $2.00 each additional. (Heavy or oversized books may incur additional charges). CANADA: (1) Priority Mail International (boxed) $36.00, each additional item $8.00 (Rates based on a books approximately 2 lb., heavier books will be price adjusted) or (2) First Class International $16.00, each additional item $10.00. (This rate is good up to 4 lb., over that amount must be shipped Priority Mail International).