Katjiuongua 9 Mar 1999 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDE to CIVIL SOCIETY in NAMIBIA 3Rd Edition

GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA GUIDE TO 3Rd Edition 3Rd Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono and Naita Marowa PJ Rejoice Compiled by GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA 3rd Edition AN OVERVIEW OF THE MANDATE AND ACTIVITIES OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN NAMIBIA Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA COMPILED BY: Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono PUBLISHED BY: Namibia Institute for Democracy FUNDED BY: Hanns Seidel Foundation Namibia COPYRIGHT: 2018 Namibia Institute for Democracy. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means electronical or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission of the publisher. DESIGN AND LAYOUT: K22 Communications/Afterschool PRINTED BY : John Meinert Printing ISBN: 978-99916-865-5-4 PHYSICAL ADDRESS House of Democracy 70-72 Dr. Frans Indongo Street Windhoek West P.O. Box 11956, Klein Windhoek Windhoek, Namibia EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.nid.org.na You may forward the completed questionnaire at the end of this guide to NID or contact NID for inclusion in possible future editions of this guide Foreword A vibrant civil society is the cornerstone of educated, safe, clean, involved and spiritually each community and of our Democracy. uplifted. Namibia’s constitution gives us, the citizens and inhabitants, the freedom and mandate CSOs spearheaded Namibia’s Independence to get involved in our governing process. process. As watchdogs we hold our elected The 3rd Edition of the Guide to Civil Society representatives accountable. -

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

Your Record of 2019 Election Results

Produced by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) Issue No 1: 2020 Your Record of 2019 Election Results These results are based on a spreadsheet received from the Electoral Commission of Namibia (ECN) on February 20 2020 with the exception that a mistake made by the ECN concerning the Windhoek Rural constituency result for the Presidential election has been corrected. The mistake, in which the votes for Independent candidate and the UDF candidate had been transposed, was spotted by the IPPR and has been acknowledged by the ECN. National Assembly Results REGION & Constituency Registered APP CDV CoD LPM NDP NEFF NPF NUDO PDM RDP RP SWANU SWAPO UDF WRP Total Votes 2019 2014 Voters Cast Turnout Turnout ZAMBEZI 45303 Judea Lyaboloma 3122 12 12 8 3 47 4 1 5 169 12 9 3 1150 5 2 1442 46.19 62.86 Kabbe North 3782 35 20 5 20 30 8 2 5 224 17 8 8 1780 14 88 2264 59.86 73.17 Kabbe South 3662 16 10 6 13 20 3 3 3 97 9 6 1 1656 4 4 1851 50.55 72.47 Katima Mulilo Rural 6351 67 26 12 25 62 12 4 6 304 26 8 7 2474 16 3 3052 48.06 84.78 Katima Mulilo Urban 13226 94 18 24 83 404 23 10 18 1410 70 42 23 5443 30 12 7704 58.25 58.55 Kongola 5198 67 35 17 21 125 10 5 5 310 32 40 17 1694 22 5 2405 46.27 65.37 Linyanti 3936 22 17 7 4 150 4 2 5 118 84 4 4 1214 12 0 1647 41.84 70.61 Sibbinda 6026 27 27 17 13 154 9 2 6 563 42 11 9 1856 27 5 2768 45.93 55.23 23133 51.06 ERONGO 113633 Arandis 7894 74 27 21 399 37 159 6 60 1329 61 326 8 2330 484 20 5341 67.66 74.97 Daures 7499 39 29 2 87 11 13 12 334 482 43 20 80 1424 1010 18 3604 54.86 61.7 Karibib 9337 78 103 -

Deconstructing Windhoek: the Urban Morphology of a Post-Apartheid City

No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 Working Paper No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Contents PREFACE 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 2. WINDHOEK CONTEXTUALISED ....................................................................... 2 2.1 Colonising the City ......................................................................................... 3 2.2 The Apartheid Legacy in an Independent Windhoek ..................................... 7 2.2.1 "People There Don't Even Know What Poverty Is" .............................. 8 2.2.2 "They Have a Different Culture and Lifestyle" ...................................... 10 3. ON SEGREGATION AND EXCLUSION: A WINDHOEK PROBLEMATIC ........ 11 3.1 Re-Segregating Windhoek ............................................................................. 12 3.2 Race vs. Socio-Economics: Two Sides of the Segragation Coin ................... 13 3.3 Problematising De/Segregation ...................................................................... 16 3.3.1 Segregation and the Excluders ............................................................. 16 3.3.2 Segregation and the Excluded: Beyond Desegregation ....................... 17 4. SUBURBANISING WINDHOEK: TOWARDS GREATER INTEGRATION? ....... 19 4.1 The Municipality's -

Safe Road to Prosperity Talking Points by the Chief

1 SAFE ROAD TO PROSPERITY TALKING POINTS BY THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, MR CONRAD M. LUTOMBI, ON THE OCCASION OF THE MEDIA BRIEFING FOR THE COMPLETION OF SECTION 3 OF THE WINDHOEK –OKAHANDJA ROAD UPGRADE PROJECT WINDHOEK –19 APRIL 2017 Members of the RA Management and Staff; Representatives from the Consultant and Contractor; Members of the Media, Good morning to you all, I wish to take this opportunity to welcome and thank you for taking time out of your busy schedules to be here this morning for the briefing of the completed section 3 of the Windhoek-Okahandja road upgrade to a dual carriageway. Section 3 covers the road from Brakwater to the Dobra River and was upgraded to a dual carriage way. This section is approximately 10 kilometres long and it is located in the Khomas Region. 1 2 Two new interchanges for access to the freeway system at Döbra South and Döbra North Interchanges were constructed. Each Interchange consists of a freeway underpass leading to the adjacent municipal arterial network, and two road-over-road bridges with four on and off ramps to connect the freeway to the underpass service road crossing split-level below the dual carriageway. Section 3 also includes the construction of a 5 kilometre service road along the eastern side of the new freeway, between the Döbra South Interchange and the Döbra North interchange. The project commenced in January 2014 and was completed in December 2016. This project was funded by the Road Fund Administration through the German funding agency KfW loan. Section 3 was completed to the tune of N$ 335 million. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Making memory work: Performing and inscribing HIV/AIDS in post-apartheid South Africa Thesis How to cite: Doubt, Jenny Suzanne (2014). Making memory work: Performing and inscribing HIV/AIDS in post-apartheid South Africa. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000eef6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Making Memory Work: Performing and Inscribing HIV I AIDS in Post-Apartheid South Africa Jenny Suzanne Doubt (BA, MA) Submitted towards a PhD in English Literature at the Open University 5 July 2013 1)f\"'re:. CC ::;'.H':I\\\!:;.SIOfl: -::\ ·J~)L'I ..z.t.... L~ Vt',':·(::. 'J\:. I»_",i'~,' -: 21 1'~\t1~)<'·i :.',:'\'t- IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl,uk PAGE NUMBERING AS ORIGINAL Jenny Doubt Making Memory Work: Performing and Inscribing HIV/AIDS in Post-Apartheid South Africa Submitted towards a PhD in English Literature at the Open University 5 July 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that the cultural practices and productions associated with HIV/AIDS represent a major resource in the struggle to understand and combat the epidemic. -

RUMOURS of RAIN: NAMIBIA's POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre Du Pisani

SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani THE .^-y^Vr^w DIE SOUTH AFRICAN i^W*nVv\\ SUID AFRIKAANSE INSTITUTE OF f I \V\tf)) }) INSTITUUT VAN INTERNATIONAL ^^J£g^ INTERNASIONALE AFFAIRS ^*^~~ AANGELEENTHEDE SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES NO 3 RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani ISBN NO.: 0-908371-88-8 February 1991 Toe South African Institute of International Affairs Jan Smuts House P.O. Box 31596 Braamfontein 2017 Johannesburg South Africa CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 POUTICS IN AFRICA'S NEWEST STATE 2 National Reconciliation 2 Nation Building 4 Labour in Namibia 6 Education 8 The Local State 8 The Judiciary 9 Broadcasting 10 THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC REALM - AN UNBALANCED INHERITANCE 12 Mining 18 Energy 19 Construction 19 Fisheries 20 Agriculture and Land 22 Foreign Exchange 23 FOREIGN RELATIONS - NAMIBIA AND THE WORLD 24 CONCLUSIONS 35 REFERENCES 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 ANNEXURES I - 5 and MAP 44 INTRODUCTION Namibia's accession to independence on 21 March 1990 was an uplifting event, not only for the people of that country, but for the Southern African region as a whole. Independence brought to an end one of the most intractable and wasteful conflicts in the region. With independence, the people of Namibia not only gained political freedom, but set out on the challenging task of building a nation and defining their relations with the world. From the perspective of mediation, the role of the international community in bringing about Namibia's independence in general, and that of the United Nations in particular, was of a deep structural nature. -

United States of America–Namibia Relations William a Lindeke*

From confrontation to pragmatic cooperation: United States of America–Namibia relations William A Lindeke* Introduction The United States of America (USA) and the territory and people of present-day Namibia have been in contact for centuries, but not always in a balanced or cooperative fashion. Early contact involved American1 businesses exploiting the natural resources off the Namibian coast, while the 20th Century was dominated by the global interplay of colonial and mandatory business activities and Cold War politics on the one hand, and resistance diplomacy on the other. America was seen by Namibian leaders as the reviled imperialist superpower somehow pulling strings from behind the scenes. Only after Namibia’s independence from South Africa in 1990 did the relationship change to a more balanced one emphasising development, democracy, and sovereign equality. This chapter focuses primarily on the US’s contributions to the relationship. Early history of relations The US has interacted with the territory and population of Namibia for centuries – indeed, since the time of the American Revolution.2 Even before the beginning of the German colonial occupation of German South West Africa, American whaling ships were sailing the waters off Walvis Bay and trading with people at the coast. Later, major US companies were active investors in the fishing (Del Monte and Starkist in pilchards at Walvis Bay) and mining industries (e.g. AMAX and Newmont Mining at Tsumeb Copper, the largest copper mine in Africa at the time). The US was a minor trading and investment partner during German colonial times,3 accounting for perhaps 7% of exports. -

4 October 1985

other prices on page 2 MPC plans UK foreign office BY GWEN LISTER PLANS HAVE REACHED an advanced stage to open an office with an undisclosed status in London to promote the interim government abroad. The Head of the Department of Interstate Relations, Mr Carl von Bach, and the new co· ordinator of the London venture, Mr Sean Cleary, have ar· rived in london to prepare for the new operation. The interim government's Minister of Justice and Information, Mr Fanuel Kozonguizi, has confirmed that the London office will be elevat ed to a new status, but the interim Cabinet must still take a final de cision on the modalities of the new campaign. It was not yet cl ear whether Mr Cleary will be permanently stationed in London. 'It is up to him' Mr Kozo nguizi said. He added that the 'extern~ l poli cy' o f the interim admini stration till had to be established. At this stage they would no~be.~eeking 'inter.na tional recognition', Mr Kozonguizi said. A fo rmer So uth African diplo mat, Mr Sean Cleary took over from Mr Billy Marais as Public Relations Consultant fo r the interim govern POLICE WATCH burning barricades in Athlone, Cape Town, the scene of continuing vio ment on October 1. In that position this week. he will be controlling public relations See inside today for the story of dramatic protests at the University of the Western Cape. MR SEAN CLEA RY - interim (Photograph by Dave Hartman of Afrapix). government's 'rovi ng ambassador'. Continued on page 3 Ministers may boycott Council BIG SPRING BY GWEN LISTER net, the participation of two vote in a Cabinet meeting ofSep COMPETITION groups in the Constitutional tember 11. -

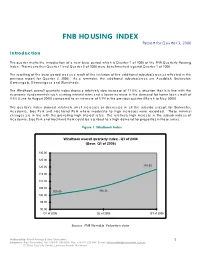

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006 Introduction This quarter marks the introduction of a new base period which is Quarter 1 of 2006 of the FNB Quarterly Housing Index. This means that Quarter 2 and Quarter 3 of 2006 were benchmarked against Quarter 1 of 2006. The resetting of the base period was as a result of the inclusion of five additional suburbs/areas as reflected in the previous report for Quarter 2, 2006. As a reminder, the additional suburbs/areas are Auasblick, Brakwater, Goreangab, Okuryangava and Wanaheda. The Windhoek overall quarterly index shows a relatively slow increase of 11.6%, a situation that is in line with the economic fundamentals such as rising interest rates and a lower increase in the demand for home loan credit of 3.6% (June to August 2006) compared to an increase of 5.9% in the previous quarter (March to May 2006). This quarter’s index showed relatively small increases or decreases in all the suburbs except for Brakwater, Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park where moderate to high increases were recorded. These minimal changes are in line with the prevailing high interest rates. The relatively high increase in the suburb indices of Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park could be ascribed to a high demand for properties in these areas. Figure 1: Windhoek Index Windhoek overall quarterly index - Q3 of 2006 (Base: Q1 of 2006) 130.00 125.00 120.00 118.55 115.00 110.00 105.00 100.00 106.22 100.00 95.00 90.00 Q1 of 2006 Q2 of 2006 Q3 of 2006 Source: FNB Namibia Valuation data Authored by: Martin Mwinga & Alex Shimuafeni 1 Enquiries: Alex Shimuafeni, Tel: +264 61 2992890, Fax: +264 61 225 994, E-mail: [email protected] 5th Floor, First City Centre, Levinson Arcade, Windhoek Brakwater recorded an extraordinary high quarterly increase of 72% from Quarter 2. -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

I.D.A.Fnews Notes

i.d. a.fnews notes Published by the United States Committee of the International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa p.o. Box 17, Cambridge, MA 02138 February 1986, Issue No, 25 Telephone (617) 491-8343 MacNeil: Mr. Parks, would you confirm that the violence does continue even though the cameras are not there? . Ignorance is Bliss? Parks: In October, before they placed the restrictions on the press, I took Shortly after a meeting ofbankers in London agreed to reschedule South Africa's a look atthe -where people were dying, the circumstances. And the best enormous foreign debt, an editorial on the government-controlled Radio South I could determine was that in at least 80% of the deaths up to that time, Africa thankfully attributed the bankers' understanding of the South African situation to the government's news blackout, which had done much to eliminate (continued on page 2) the images ofprotest and violence in the news which had earlier "misinformed" the bankers. As a comment on this, we reprint the following S/(cerpts from the MacNeil-Lehrer NewsHour broadcast on National Public TV on December 19, 1985. The interviewer is Robert MacNeil. New Leaders in South Africa MacNeil: Today a South African court charged a British TV crew with Some observers have attached great significance to the meeting that took inciting a riot by filming a clash between blacks and police near Pretoria. place in South Africa on December 28, at which the National Parents' The camera crew denied the charge and was released on bail after hav Crisis Committee was formed.