Towards a History of Workers As Environmentalists in British Columbia and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spot the Island

IISLANDSLAND WILDLIFE SSttrraaiit ooff GGeeoorrggiiaa NNewsletterewsletter Inside UUnniittiinngg TThhee SSaalliisshh SSeeaa ~~ FFrroomm CCooaasstt ttoo CCooaasstt ttoo CCooaasstt Volume 22 Number 23 2010 Year End Edition $2 at Selected Retailers Canadian Publications Mail Product Sales Agreement Nº 40020421 Photo: Derek Holzapfel Plumper Sound parking lot. Four (you can’t see one of them) idle freighters waiting for entry to the Port of Vancouver on November 28. Queens in trouble—Southern Gulf Commentary by Sara Miles Counting Carbon Islands’ ferries have a tough season Thank you, Bolivia! Thank you for giving makes up the government? You and I. The substitute Bowen Queen is still formidable variety of wind and current me the courage to say what I was too Our inaction on climate change makes suffering from overload problems on Route conditions. In fact, one of the most difficult Canadian to say: when it comes to climate me want to cry. Polar bears are just the Nº5. Ferry crews have been almost heroic in routes on the ferry system; in contrast to the change and carbon talks, we are big, fat cutest little guys and our irresponsibility is getting people home. Meanwhile, all has not port-to-port Comox–Powell River route. hypocrites. destroying them forever. been plain sailing for the Queen of Burnaby, Route Nº9’s fourth port of call, Sturdies On Day 2 of the COP-16 negotiations in I try to be environmentally friendly and borrowed from Comox–Powell River to Bay, is particularly exposed to southeast Cancun, Mexico, Bolivia’s ambassador to choose to walk or cycle as much as I can, but replace the Queen of Nanaimo (in refit) on winds from the Strait of Georgia, which the UN criticized the nations who are car drivers everywhere seem to have a plot the Southern Islands-Tsawwassen route . -

Our Cultural Heritage Places

HERITAGE 2006 PATRIMOINEPATRIMOINE 20062006 Our Cultural Heritage Places Nos lieux culturels patrimoniaux CONTENTS TABLE DES MATIÈRES Canada’s Built Heritage Le patrimoine bâti à vocation For Culture 1 culturelle du Canada 1 British Columbia Colombie-Britannique Orpheum Theatre 7 Théâtre Orpheum 7 Alberta Alberta Banff Park Museum 9 Musée du Parc-Banff 9 Saskatchewan Saskatchewan Danceland 11 Danceland 11 Dance Halls In Canada 14 Salles de danse au Canada 14 Manitoba Manitoba The Virden Auditorium Theatre 15 Le Virden Auditorium Theatre 15 Yukon Yukon Palace Grand Theatre 17 Palace Grand Theatre 17 Ontario Ontario St. Lawrence Hall 19 St. Lawrence Hall 19 Victoria Memorial Museum 22 Musée commémoratif Victoria 22 Quebec Québec Montreal Museum Of Fine Arts 25 Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal 25 Granada Theatre 27 Théâtre Granada 27 Community Action Saves L’action communautaire sauve Historic Theatres 28 des théâtres historiques 28 Newfoundland And Labrador Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador Society Of United Fishermen Society Of United Fishermen Lodge (SUF#1) 29 Lodge (SUF #1) 29 New Brunswick Nouveau-Brunswick Capitol Theatre/Imperial Theatre 31 Théâtre Capitol/Théâtre Imperial 31 Prince Edward Island Île-du-Prince-Édouard Victoria Community Hall 33 Victoria Community Hall 33 Nova Scotia Nouveau-Écosse Halifax Public Gardins 35 Les Jardins publics de Halifax 35 Finding Out More About Cultural Se renseigner sur les immeubles Buildings And Places 38 et endroits culturels 38 If You Want To Read More 39 À lire au sujet du patrimoine Websites 40 culturel -

Debates of the Legislative Assembly

3rd Session, 37th Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY (HANSARD) Monday, February 18, 2002 Morning Sitting Volume 3, Number 5 THE HONOURABLE CLAUDE RICHMOND, SPEAKER ISSN 0709-1281 PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Honourable Iona Campagnolo 3RD SESSION, 37TH PARLIAMENT SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Claude Richmond EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council..........................................................................................................Hon. Gordon Campbell Minister of State for Intergovernmental Relations................................................................................................... Hon. Greg Halsey-Brandt Deputy Premier and Minister of Education .........................................................................................................................Hon. Christy Clark Minister of Advanced Education............................................................................................................................................Hon. Shirley Bond Minister of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries..................................................................................................................Hon. John van Dongen Attorney General and Minister Responsible for Treaty Negotiations.................................................................................. Hon. Geoff Plant Minister of Children and Family Development..................................................................................................................Hon. -

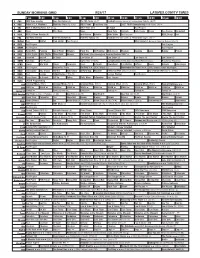

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

Cinemati • TRADE NEWS • Full Implementation of Law Due in 0C Private Labs Suffer From

CINEMAti • TRADE NEWS • Full Implementation of law due in 0C Private labs suffer from MONTREAL - By the end of gross; and the factors which Once the regulations are ap NF B IT Fproductions October, the Quebec Cabinet should determine the 'house proved, the Cabinet will then 15 projects since the begin is expected to have approved nut' or the cost of operating a promulgate the articles of the MONTREAL - Figures recently the final version of the regula theatre. law which are pertinent. released by the National Film ning of the Broadcast Fund for tions of the Cinema Law. Ap Guerin does not foresee any Board to Sonolab's president budgets totalling 532,528,000. proval of the 140 articles of the parts of the law being set aside, Andre Fleury reveal for the Of this amount, the NFB spent regulations will permit prom For articles concerning film and commented that the first time the ventilation of in $4,399,000 internally on tech ulgation of the remaining arti distribution as defined in the cinema dossier is one of the vestments made by the NFB on nical services while it spent cles of the law which was pass regulations see page 44, minister's priorities. Richard productions involving Telefilm only 565,000 on the same ser ed by the National Assembly has already announced that he Canada and are sure to fuel the vices in the private sector. on June 22, 1983. will not stand for re-election, long-standing battle involving Emo explains in her letter to The final, public consulta Other briefs presented at the but has promised to see the the Board and the private-sec Fleury that the Board's policy tion on the regulations took hearings dealt with video-cas Cinema Law completed before tor service houses. -

SOCIAL UNDERSTANDING and CULTURAL AWARENESS JIM WOODS, DIRECTOR of TRIBAL AFFAIRS, SPECIAL ASSISTANT to the DIRECTOR Native American Tribes Are Here

Working with Tribes SOCIAL UNDERSTANDING AND CULTURAL AWARENESS JIM WOODS, DIRECTOR OF TRIBAL AFFAIRS, SPECIAL ASSISTANT TO THE DIRECTOR Native American Tribes are here 574 Recognized Tribes in the United States 29 Federally Recognized Tribes in Washington 21 + 2 Treaty Tribes 8 Executive Order Tribes Tribes with Fishing Rights 24 Tribes with off-reservation Hunting Rights Out of State Tribes with rights in Washington Working with our tribal partners The overview: History of Tribal Governments Cultural Relevance & Differences Awareness of Native Lifeways Social Characteristics Stewardship Shared Management and Responsibilities Professional Perspective Resiliency Culture is not a divide. Although Indian tribes are sovereign, that sovereignty is not absolute. It has been challenged, defined, and battled over throughout U.S. history. History of Tribal Governments Tribes have been on this Continent and here in the Pacific Northwest for thousands of years. Historically the Makah believe Orca transformed into a wolf, and thus transforming again into Man. Pre-1492: Pre-Columbus Period Native people lived in organized societies with their own forms of governance for thousands of years before contact with Europeans. Historic Ancient Chinese Explorers traded with WA Coastal Tribes early 1400’s 1513- Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the first European to sight the Pacific Ocean, when he claimed all lands adjoining this ocean for the Spanish Crown. In the vicinity of the Duwamish River and Elliott Bay where in 1851 the first U.S. settlers began building log cabins, the Duwamish tribe occupied at least 17 villages. The first non-Natives to settle the area were farmers who selected their claims on the Duwamish River on September 16, 1851. -

Spirit of Flight Experimental Aircraft Association Chapter 14: San Diego, CA

Spirit of Flight Experimental Aircraft Association Chapter 14: San Diego, CA January 2019 Steep Approach at Saanen-Gstaad, Switzerland. Photo by Tobias Burch. Table of Contents 8 December Program Notes ..................... Gene Hubbard Page Topic/Author 10 The Way We Were, 2004 ........................ Donna Ryan 11 Renew Your Membership Today! ........... Donna Ryan 2 Chapter Briefing .........................Chapter 14 Members 12 December 2018 Board Meeting ............... Donna Ryan 4 President’s Message ............................. Gene Hubbard 12 Upcoming Programs ............................... Kerry Powell 4 Young Eagles Report............................... Mark Albert 13 Marketplace 5 Carbon Cub Build Progress .................... Tobias Burch 13 Upcoming Events 6 Propeller Design, Chapter 2 ...................... Mark Long 13 Award Banquet Flyer 7 New Members ......................................... Donna Ryan 14 Around Chapter 14 ......... photos by Chapter Members 7 The Kennedy Caper ................................. Chuck Stiles 15 Membership Renewal Form Spirit of Flight - Page 1 Chapter Briefing By EAA Chapter 14 Members Chapter Activities: Information provided by Bob Osborn and others. Week ending December 1: It was a windy and cold week at EAA Chapter 14. But that didn’t stop a good group from enjoying Bill Browne’s delicious meal of make-your-own sandwiches, featuring roast beef, ham, turkey, cheese, lettuce and tomatoes. Some chips and chocolate chip cookies rounded out the meal. Joe Russo and Gene Hubbard started working on the Stits Playboy project: wing frames were attached and the ailerons were taken off. Nice progress! Blueberry pancakes, waffles, sausage, and eggs, a popular breakfast for nearly 40 people on a third Saturday. 12/15 busy event. Kevin Roche had a constant waiting line as he prepared blueberry pancakes, sausage, and eggs. -

May 16, 2012 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, MAY 16, 2012 • VOL. 23, NO. 2 $1.25 Congratulations to Ice Pool Winner KLONDIKE Mandy Johnson. SUN Breakup Comes Early this Year Joyce Caley and Glenda Bolt hold up the Ice Pool Clock for everyone to see. See story on page 3. Photo by Dan Davidson in this Issue SOVA Graduation 18 Andy Plays the Blues 21 The Happy Wanderer 22 Summer 2012 Year Five had a very close group of The autoharp is just one of Andy Paul Marcotte takes a tumble. students. Cohen's many instruments. Store Hours See & Do in Dawson 2 AYC Coverage 6, 8, 9, 10, 11 DCMF Profile 19 Kids' Corner 26 Uffish Thoughts 4 TV Guide 12-16 Just Al's Opinion 20 Classifieds 27 Problems at Parks 5 RSS Student Awards 17 Highland Games Profiles 24 City of Dawson 28 P2 WEDNESDAY, May 16, 2012 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to The Westminster Hotel Live entertainment in the lounge on Friday and Saturday, 10 p.m. to close. More live entertainment in the Tavern on Fridays from 4:30 SEE AND DO p.m.The toDowntown 8:30 p.m. Hotel LIVE MUSIC: - in DAWSON now: Barnacle Bob is now playing in the Sourdough Saloon ev eryThe Thursday, Eldorado Friday Hotel and Saturday from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. Any small happening may Food Service Hours: 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., seven days a week. Check out need preparation and planning, so let us know in good time! To our Daily Lunch Specials. -

ELECTIONS WITHOUT POLITICS: Television Coverage of the 2001 B.C

ELECTIONS WITHOUT POLITICS: Television Coverage of the 2001 B.C. Election Kathleen Ann Cross BA, Communication, Simon Fraser University, 1992 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School of Communication @ Kathleen Ann Cross, 2006 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSrrY Spring 2006 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME Kathleen Cross DEGREE PhD TITLE OF DISSERTATION: ELECTIONS WITHOUT POLITICS: Television Coverage of The 2001 BC Election EXAMINING COMMITTEE: CHAIR: Dr. Shane Gunster Dr. Richard Gruneau Co-Senior Supervisor Professor, School of Communication Dr. Robert Hackett Co-Senior Supervisor Professor, School of Communication Dr. Yuezhi Zhao Supervisor Associate Professor, School of Communication Dr. Catherine Murray Internal Examiner Associate Professor, School of Communication Dr. David Taras External Examiner Professor, Faculty of Communication and Culture, University of Calgary DATE: 20 December 2005 SIMON FRASER ' UNIVERSITY~I bra ry DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection, and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

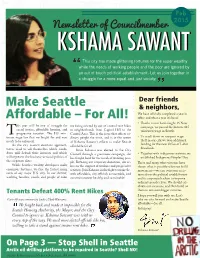

Make Seattle Affordable—For All

Feb 2015 Newsletter of Councilmember KSHAMAKSHAMA SAWANTSAWANT This city has made glittering fortunes for the super wealthy while the needs of working people and the poor are ignored by an out of touch political establishment. Let us join together in a struggle for a more equal and just society. Dear friends Make Seattle & neighbors, We have officially completed a year in Affordable – For All! office and what a year it’s been! • Thanks to our hard-fought 15 Now his year will be one of struggle for are being evicted by out-of-control rent hikes campaign, we passed the historic $15 racial justice, affordable housing, and in neighborhoods from Capitol Hill to the minimum wage in Seattle. progressive taxation. The $15 min- Central Area. This is the issue that affects -or imum wage law that we fought for and won dinary people the most, and is at the center • To crack down on rampant wage T theft in our city, we won additional needs to be enforced. of Kshama Sawant´s efforts to make Seattle funding for the new Office of Labor As the city council elections approach, affordable for all. Standards. voters need to ask themselves which candi- Since Kshama was elected to the City dates will defend their interests and which Council through a grassroots campaign, she • Together with indigenous activists, we will represent the business-as-usual politics of has fought hard for the needs of working peo- established Indigenous Peoples’ Day. the corporate elites. ple. Refusing any corporate donations, she re- These and many other victories have While Seattle’s wealthy developers make lies on the support of workers and progressive shown what is possible when we build enormous fortunes, we face the fastest rising activists. -

Brigadier General Bob Cardenas to Speak on March 2Nd!

Volume 28: Issue 2 ● February 2013 A Publication of the Pine Mountain Lake Aviation Association Brigadier General Bob Cardenas to Speak on March 2nd! Where: The McGowan’s Hanger at 6:00 PM March 2nd 2013 rigadier General Robert L. “Bob” Cardenas was born in Merida, Yucatan, Mexico on March 10th, 1920, and moved to San Diego with his parents at the age of five. During his teenage years, Cardenas built model B airplanes and helped local glider pilots with their dope-and-fabric construction, often bumming rides with the pilots in the gliders he helped to repair. A bright student with excellent grades in Mathematics and Physics at high school, Cardenas was selected to attend the San Diego State University. During 1939 Cardenas began a long and distinguished military career when he joined the California National Guard. In September of 1940, Cardenas entered into aviation cadet training, graduated and received his pilot wings & commission as a second lieutenant during July of 1941. Cardenas was sent to Kelly Field, Texas to become a flight instructor, then onto Twentynine Palms, California to establish the U.S. Army Air Force’s glider training school and followed this by becoming a Flight Test Officer and then Director of Flight Test Unit, Experimental Engineering Laboratory, Wright Field Ohio. Cardenas’ next assignment was to the 44th Bomb Group and arrived in England on January 4th, 1944. Based at Shipdam, Norfolk, Cardenas flew his first mission on January 21st in B-24H “Southern Comfort”. On March 18th, 1944 (on his twentieth mission) while flying as command pilot aboard B-24J “Sack Artists” the aircraft in which Cardenas was flying was badly damaged by anti-aircraft fire and enemy fighters.