Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

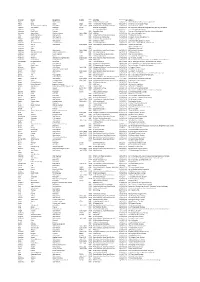

Surname Names Rating/Rank Number

Surname Names Rating/Rank Number ServiceUnit/Ship Date DeatAge Address Adam John Able Seaman MM SS War Patrol (Liverpool) 10/08/17 35 Whites Building, William Street, Tayport, Fife. Aitken David Bosun 15625 MM HM Australian Transport Ajana 02/11/18 43 Strathmore Hotel, Coupar Angus. Alcorn Alexander Menzies Gilchrist Petty Officer Clyde Z/5593 RNVR Hawke Battalion, Royal Naval Division 27/09/18 24 4 Stewart Street, Lochee. Alderson John William Passenger Civilian SS California (Glasgow) 07/02/17 35 Son of Thomas Alderson & Margaret Butson, Burnley, Lancashire. Alderson Claude Passenger Civilian SS California (Glasgow) 07/02/17 3 Son of John William Alderson Alexander David Buick Engineer MM Australian Vessel 25/04/18 Brother of Eliza Alexander, Riverview, Milton of Monifeith. Alexander James Robert Ordinary Seaman Clyde Z/8148 RNVR HMS Ebro 21/03/17 36 63, Fisher St, Broughty Ferry. Allan Martin Henderson Able Seaman 5862A RNR Hawke Battalion, Royal Naval Division 04/11/18 29 176 Ferry Rd, Dundee. Allan David Anderson Chief Engineer MM SS Mexico City (Hong Kong) 05/02/18 48 1 Leebank Terrace, Broughty Ferry. Allardice William Nicoll Third Engineer MM SS Therese Heymann (London) 25/12/14 23 85 Hilltown, Dundee. Allander John Able Seaman MM SS Watchful (Wick) 01/12/15 52 Lived in Dundee, address not known. Anderson Alexander Ireland Second Engineer MM SS Sowwell (London) 19/04/17 24 Born Dundee. 109 Talbot Rd, South Shields. Anderson John G Able Seaman Clyde Z/5648 RNVR Anson Battalion, Royal Naval Division 17/11/16 27 9 Patons Lane Dundee. -

Periodicals by Title

I think this is now the largest list of books and magazines in the world on Motor Vehicles. I think I maybe the only person trying to find and document every Book and Magazine on Motor Vehicles. This is a 70+ year trip for me all over the world. Some people have called this an obsession, I call it my passion. This has been a hobby for me since I was about 10 years old. I don’t work on it everyday. I don’t do this for money. I don't have any financial help. I have no books or magazines for sale or trade. I do depend on other Book and Magazine collectors for information on titles I don’t have. Do you know of a Book, Magazine, Newsletter or Newspaper not on my list?? Is my information up to date?? If not can you help bring it up to date?? I depend on WORD-OF-MOUTH advertising so please tell your friends and anyone else that you think would have an interest in collecting books and magazines on motor vehicles. I am giving my Book and Magazine Lists to Richard Carroll to publish on his web - site at www.21speedwayshop.com take a look.. All I am collecting now is any issue of a title. If you are the first to send me a copy of a magazine I don’t have I will thank you with a mention under the title. Because of two strokes and a back injury from falling down the stairs this is about all I can do now. -

Last Voyage of the S.S.Clan Alpine

Last Voyage of the S. S. "CLAN ALPINE" On 31st October 1960 while on voyage from Glasgow to Chittagong with general cargo, the vessel was caught in a cyclone while anchored off Chittagong. Driven from her moorings she was left high and dry in paddy fields at Skonai Chori, 11 miles N.N. W. of the entrance to the Kharnapuli River. The vessel was declared a constructive total loss, and the cargo was discharged into lorries. On February 14th 1961 she was sold to East Bengal Trading Corporation Ltd. and broken up as she lay. John Morris, brother of Staff Captain Les, was 3rd Engineer on the eventful trip and has written this account of it. It will be concluded in the next edition.. S. S. "CLAN ALPINE" (1945-1957) and (1959-1960) O.N. 169016. 7168 g. 4253 n. 3 Cylinder, Triple expansion Steam engine, 2510 nhp. Built by G. Clark Ltd. Sunderland. Launched 17th January 1942 and completed April 1942 by J. L. Thompson & Sons Ltd., Sunderland (Yard No. 615) as “EMPIRE BARRIE” for the Ministry of War Transport. Allan, Black & Co., Sunderland, appointed managers. In 1944 Cayzer Irvine & Co. Ltd. appointed managers. Purchased in 1945 by Clan Line Steamers and renamed "CLAN ALPINE". In 1952 underwent strain comparison tests with the welded "OCEAN VULCAN". 1957 registered under Bullard, King & Co. Ltd. and renamed “UMVOTI”. 1959 registered under The Clan Line Steamers Ltd. and renamed "CLAN ALPINE" again. In 1960 sold to Japanese breakers with delivery November 1960. I had just been promoted to 3rd Engineer Officer, and after the usual stint of relieving duties around the coast, I was appointed to the "Clan Alpine" which was loading at Vittoria Dock in Birkenhead. -

Sentinel 23 April 2015

THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. www.sams.sh Vol. 4,SENTINEL Issue 5 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 23 April 2015 “A Fantastic Opportunity” Celebrating Five Years page 9 of G-Unique Designs Liam Yon, SAMS good feeling about the business she, “never imagined it would be this successful.” Giselle started making jewellery, in particular ear- This month G-Unique Designs, which specialises rings, as a hobby. This eventually grew into a, “cottage in jewellery and accessories, is celebrating fi ve years industry,” where she would create jewellery products since its start in 2010. “It certainly feels very invigo- in her home and sell them via outlets around the island. rating,” said Giselle Richards, owner of G-Unique De- “Then I decided to develop it further,” said Giselle, signs, “we are very proud to reach this milestone.” “because my spare bedroom just wasn’t big enough.” Starting in 2010, Giselle envisioned G-Unique design- She rented a workshop where she would create her ing jewellery that St Helena could be proud of, “from jewellery. Giselle then decided that there needed to a professional standpoint.” Although she always had a be, “an actual G-Unique continued on page 3 Sparkle Jewellery Getting Down and Dirty - L&C page 18 Environmental Risk Senior Managers Manager, Mike Durnford Clean Toilets Richard Wallis, SAMS Two senior managers from within the Environment and Natural Resources Division (ENRD) rolled up their sleeves and scrubbed the islands public toilets in an effort to better understand the amount of work that goes into providing a better service. -

Scenic Scotland, Gardens and Archaeology Tours

% WHEN YOU 5off PAY IN FULL 2020 or 2nd Edition LOW Scenic Scotland, Gardens From $75 DEPOSIT and Archaeology Tours Welcome As you may well know, the beginning of a new year means the arrival of our exciting second edition brochure. 2019 has been a record year for us, as not only did we win the gold prize for Best Coach Holiday Company, we also won silver for Best Special Interest Holiday Company at the prestigious British Travel Awards. In addition, we also took more guests on vacation than ever before – and to more destinations. So, what can you expect from us in 2020? Let us tell you... Firstly, we wanted to give you a little treat to celebrate the new year so we’ve launched two special January offers, which mean you’ll be able to book your Brightwater Holidays trip for less. You can choose to pay in full at the time of booking and receive 5% off your total, which could save you up to $435, or you can take advantage of our low deposit offer, which starts from just $75pp. Both offers will run until 2nd February, 2020, so there is no better time to book than right now! Next, we have a selection of brand-new tours that can take you to new places and invite you to experience new things. Firstly, we’ve launched a selection of European River Cruises which will take in some outstanding gardens and historic cities. We’ve added another Dutch cruise, in addition to our Bulbfields vacation, which can take you to some of the outstanding gardens of the Low Countries in the summer. -

Sentinel 141113

THE South Atlantic Media Services, Ltd. www.sams.sh Vol. 3,SENTINEL Issue 34 - Price: £1 “serving St Helena and her community worldwide” Thursday 13 November 2014 Remembrance Day Island Marks 100 years since the First World War Generous Donation page 3 see pages 2 & 3 BAM Meets Chamber of Commerce Cllr Henry Off to Feedback Indicates a Successful Meeting JMC page 5 Ferdie Gunnell, SAMS ticularly for farming and fi sheries. Fisheries empha- sized the importance of balanced development in both BAM team members Doug Winslow, David Finan the offshore and inshore fi sheries so that one comple- and Morgan Riley met the Chamber of Commerce ments the other. Farming representatives emphasized (COC) on 6 November to hear about private sector is- the importance of improved storage and chill rooms sues. BAM are considering SHG’s current budget per- infrastructure to benefi t all farmers. formance and requirements for the next three fi nancial Farmers also spoke about invasive species control years. which is, “threatening both arable production and ani- Mr Winslow said BAM was trying to build a picture mal farming.” EU money obtained some years ago to of where revenues are coming from and taking into ac- control those has long since been exhausted and no fur- count restrictive monies available. ther money has been forthcoming on any big scale to The COC President, Dr Corinda Essex, said it was very actually tackle the problem. Some felt the situation is important for the DfID team to be aware of the issues worse now than ever. raised, “so they can understand -

Download Chapter

HUDDERSFIELD’S ROLL OF HONOUR 1914–1922 1 ABBY, ALBERT. Private. No 53069. 1/4th Duke RAILWAY DUGOUTS (TRANSPORT FARM) of Wellington’s Regiment. Born Huddersfield BURIAL GROUND. Grave location:- Plot 6, 1886. Son of John M. and Hannah Abby, 22 Ash Row O, Grave 27. ROH:- Armitage Bridge War Grove Road, Huddersfield (1901 Census). Married Memorial. Miranda Harrison in 1908. Lived 27 Slades Road Golcar, father of 3 children. Employed at Messrs ADAMSON, WILLIAM BURGESS. Acting John Crowther and Sons, woollen spinners, Sergeant. No 3/11505. 9th Battalion Duke of Milnsbridge. Enlisted July 1918. Embarked for Wellington’s Regiment. Born Scarborough. France after the signing of the Armistice and had Son of Benjamin and Ann Adamson. Came to only been there for three days when he was killed Huddersfield three years before the outbreak of whilst clearing the battlefield, 10.12.1918, aged war. Lived 5 Cross Grove Street, Huddersfield. 32 years. Buried DOUAI BRITISH CEMETERY. Husband of Lilian Adamson. Employed by Mr Grave location:- Row C, Grave 34. ROH:- St. G. S. Jarmaine of Dalton. Enlisted September John’s Church, Golcar. 1914. Had served in the Boer War. Killed in action, 15.8.1917. Buried in BROWN’S COPSE ACKROYD, ARTHUR. Private. No 254457. CEMETERY. Grave location:- Plot 4, Row A, Labour Corps. Formerly No 12444 Duke of Grave 55. Wellington’s Regiment. Born Clayton West. Husband of Mary Ackroyd, High Street, Clayton ADDERLEY, FRANK. Private. No 46524. 24th West. Enlisted Huddersfield. Died at home, (Tyneside Irish) Battalion Northumberland 21.2.1918, aged 41 years. Buried ALL SAINTS Fusiliers. -

Panama Canal Record

THE PANAMA CANAL RECORD VOLUME 27 Gift ofthe Panama Canal Museum UNiV. OF FL. L B JUL 1 7 m Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/panamacanalr27193334isth THE PANAMA CANAL RECORD PUBLISHED MONTHLY UNDER THE AUTHORITY AND SUPER- VISION OF THE PANAMA CANAL AUGUST 15, 1933 TO JULY 15, 1934 VOLUME XXVII WITH INDEX THE PANAMA CANAL BALBOA HEIGHTS, CANAL ZONE 1934 THE PANAMA CANAL PRESS MOUNT HOPE, CANAL ZONE 1934 For additional copies of this publication address The Panama Canal, Washington, D. C, or Balboa Heights, Canal Zone. Price of bound volumes, $1.00; for foreign postal delivery, $1.50. Price of current subscription, $0.50 a year, foreign Sl.OO. .. ... THE PANAMA CANAL RECORD OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE PANAMA CANAL. PUBLISHED MONTHLY. Subscription rates, domestic, $0.50 per year; foreign, $1.00; address The Panama Canal Record, Balboa Heights, Canal Zone, or, for United States and foreign distribution. The Panama Canal, Washington, D. C. Entered as second-class matter February 6, 191.S, at the Post Office at Cristobal, C. Z., under the Act ol March 3, 1S79. Certificate.—By direction of the Governor of The Panama Canal the matter contained herein is published as statistical information and is required for the proper transaction of the public business. Volume XXVII. Balboa Heights, C. Z., August 15, 1933. No. i. Traffic Through the Panama Canal in July 1933 The total vessels of all kinds transiting the Canal during the month of July in the two -

COMMANDER Photographs

Oliver Lodwick Wolfard U.S. Naval Academy class of 1911. (108) Photograph ( right ) credit is number (108). Again, cm 11 February there wu another re1cue. The story or 1hia 11 more ocaplete. CD 26 January the s. s. SAN ARCADIO, a aeven thousand tcm. Briti1h tanker with t.t.tty ottioera a.d men, put out trm Houatcm., Texaa, loaded with oil and bound for Halif'u, BoYa Sootia. FiTe day1 out, in po1iti<11 SS-lOI and 6S-flCIJ, at about 2200 LZT, they were torpedoed tir1t att md th• forward cm the 1tarboard aide. Arter tirtem minute• or ettort to am rlldio ocmtact the ahip wu in auoh c diticm. that it had to be abandcm.ed. 14-P-7, Lieut- enant J. A. JAAP O·Clllll.ailding tound nine survivor a in poaiticn M-281 and 62-5af. Th• plan• l•nded at , took the peraQDNtl aboard and returned th• to Ber C.'t) muda. Aa a reault or ia aoticn Lieutenant J01eph Abraham Jaap, USI, waa awarded the Diatinguia ed Flying Croat VP-74 - 1942 Eor inea 817llJ4 ,lf<h1f.AflAroadio Oil£•g~ 7co1t141 lOOA1.12 1 IM:olirtt"' 12 OL,41 19354m.o 1RarlIVolff.Ldand.& rlaOUli:lliPl'lllcOo. Ld. 6·0j60·21s2·~0D40DBrlti1h ~IIll1.i6 (,'-66•sI' .C.SA.OO'tN i28· • · ; GYJ c.-u11aSlrrH ,,Ukn.Nv. 1-0,· U O Glasgo" f •& 16BO}tl'<•• fUBlBO!b 26 •If P'Jb'B~4 ' F32' . F. _ !Dk,2"d~kclcar~fcorqo1o•ki , •:<LM< I t';il; • Uo¥1'•AtCl' C,llDB~Ji!~•l'I llllTf!G'Y8!11FP 1 881.~PTOOI arlaodkWola",Ld.Gll. -

The Haj in the Urbs Prima in Indis: the Regulation of Pilgrims and Pilgrim Traffic in Bombay, 1880 to 1914

The Haj in the Urbs Prima in Indis: The Regulation of Pilgrims and Pilgrim Traffic in Bombay, 1880 to 1914 by Nicholas Sebastian Lombardo A thesis submitted in conformity with the degree requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of Geography and Planning University of Toronto © Copyright by Nicholas Sebastian Lombardo, 2012 The Haj in the Urbs Prima in Indis: The Regulation of Pilgrims and Pilgrim Traffic in Bombay, 1880 to 1914 Master of Arts, 2012 By Nicholas Sebastian Lombardo Department of Geography and Planning University of Toronto Abstract In this thesis I argue that the management of Muslim pilgrims and the Haj traffic in Bombay was the result of the localization of an international regime of regulation aimed at controlling Hajis as mobile threats to public health and imperial security. International scientists, doctors, and politicians problematized Hajis as diseased, dangerous and disorderly through discourse produced in print material and at international conferences taking place across the globe. Local, elite concerns over their own power, Bombay’s urban spatial order, and the city’s international trade shaped the way these larger global and imperial projects were implemented in Bombay. These findings point to the importance of local, place-based social, political and economic structures in the day-to-day governance of empire. ii Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been completed without the generous support of a number of people. I owe a very large debt of gratitude to my supervisor Robert Lewis. I am especially grateful for the opportunities he provided to explore the archives in London and Chicago, without which I never would have come upon my thesis topic in the first place. -

WW1 Seamen's Roll of Honour

WW1 Seamen's Roll of Honour Surname Names Rating/Rank Adam John Able Seaman Aitken David Bosun Alcorn Alexander Menzies Gilchrist Petty Officer Alderson John William Passenger Alderson Claude Passenger Alexander David Buick Engineer Alexander James Robert Ordinary Seaman Allan Martin Henderson Able Seaman Allan David Anderson Chief Engineer Allardice William Nicoll Third Engineer Allander John Able Seaman Anderson Alexander Ireland Second Engineer Anderson John G Able Seaman Anderson John A Anderson Allan Anderson William Able Seaman Anderson John Houvelsronde Acting Leading Seaman Anderson Allan John Fourth Engineer Anderson Joseph Master Anderson William G Able Seaman (Higher Grade) Anderson Charles Henry Leading Fireman Attwood DSC Douglas Ramsden Lieutenant Bain Donald Chief Engineer Baldy David Cramb Chief Steward Balbirnie William Petty Officer Bannerman James Shipmaster and First Mate Barber Richard Able Seaman Barnett Joseph Stoker Barrie A B First Engineer Bateman Harry Lance Corporal Battes David M'I Able Seaman Baxter James Leading Seaman Baxter Charles Kinmont Second Engineer Beaton Henry Alexander Engineer Lieutenant Beaton John Duncan Engine Room Artificer Second Class Bell Andrew Greaser WW1 Seamen's Roll of Honour Bell Duncan Deck Hand Bennett William Passenger Bernard David Steward Bernard George First Mate Bertie William Able Seaman Beveridge Robert Able Seaman Bigsby Thomas James Leading Seaman Birse John Apprentice Bisset David Findleton Ordinary Seaman Blackburn Layton Leading Seaman Blackie W Fireman Blackwood Thomas -

Part IV.—Marine and Mercantile

C niU m © oterinroat IPuMfeljtsft trjt S u ito r tig. N o . 5,740—FRIDAY, DECEMBER 7, 1900. PABT I.—General: Minutes. Proclamations, Appointments, P a r t III.—Provincial Administration. and Gejheral Government Notifications. PART IY.—Marine and Mercantile. Part II.—Legal and Judicial. P a r t Y.—Municipal and Local. Separate paging is given to each Part in order that it may he filed, separately. Part IV.—Marine and Mercantile. PARK PAGE Board of Trade Notices . 261 Returns of Imports, Exports, and Bonded Goods 267 Notices to Mariners . 263 Railway Traffic Returns Notifications of Quarantine Trade Marks Notifications 264 BOARD OF TRADE NOTICES* T HE following notices of the Board of Trade (Fisheries and Harbour Department) are published for general information :— (F. & H. 14,823.) London, November 7, 1900. The Board of Trade have received, through the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, a copy of a Despatch from Her Majesty’s Representative at St. Petersburg, intimating that Bushire,‘the Island of Kishen, and Bunder Abbas are free from plague. (F. & H. 14,914.) London, November 7, 1900. The Board of Trade have received, through the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, a copy of a Telegram from Her Majesty’s Representative at Constantinople, intimating that free pratique is granted to arrivals from Alexandria, medical inspection and disinfection imposed, susceptible merchandise still rejected. (F. & H. 14,915.) London, November 7,1900. The Board of Trade have received, through the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, a copy of a Telegram from Her Majesty’s Representative at Teheran, intimating that Tamatave has been declared foul.