OD Strategies and Workplace Bullying

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incurable Psychopaths?

Incurable Psychopaths? Marianne Kristiansson, MD Treatment, comprising pharmacotherapy and an educational program based on cognitive behavior therapy, of four psychopathic, criminal men fulfilling the crite- ria for borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder is de- scribed. The diagnoses were made during a forensic psychiatric evaluation. An estimation of the capacity of the central serotonergic system was performed by analysing the platelet monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity. The pharmacotherapy was combined with an educational program involving strategies for developing better impulse control. All four men had earlier been regarded as resistant to conventional therapy. In the present cases, a combined psychosocial and biolog- ical approach seemed to be effective in developing an increased control of im- pulses, leading to improved coping strategies. Controlled studies are needed in order to clarify whether the described treatment program proves beneficial. Psychopathy, as originally described by personality disorder according to DSM- Cleckley,' comprises a set of clinical 111-R.~ characteristics including superficial The possibility of curing or even trying charm, unreliability, untruthfulness, lack to treat criminal psychopathic individuals of remorse or shame, failure to learn by is often looked upon as futile. Most treat- experience, incapacity for love, general ment programs involve various psycho- poverty in major affective relations, and social interventions and little effort has failure to follow any life -

Employee Onboarding

Strategic Onboarding: The Effects on Productivity, Engagement, & Turnover By: Lisa Reed, MBA, SPHR Onboarding Defined A systematic and comprehensive approach to integrating a new employee with an employer and its culture, while also ensuring the employee is provided with the tools and information necessary to becoming a productive member of the team (1). How Important is Onboarding? 43% of employees state the opportunity for advancement was the key factor in deciding whether or not to stay with an organization, and the onboarding process, or lack thereof, was a main factor in determining advancement potential within a company (2). EMPLOYEE PRODUCTIVITY What is Employee Productivity? An assessment of the efficiency of a worker or group of workers, which is typically compared to averages, is referred to as employee productivity (3). Costs of Employee Unproductivity More than $37 billion dollars annually is spent by organizations in the US to keep unproductive employee in jobs they do not understand (4). What Effect Does Strategic Onboarding Have On Employee Productivity? Only 49% of new employees without formal onboarding meet their first performance milestone (5). In contrast, 77% of employees who are provided with a formal onboarding process meet first performance milestones (6). Employee performance can increase by 11% with an effective onboarding process, which can also be linked to a 20% increase in an employee’s discretionary effort (7). EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT What is Employee Engagement? Employee engagement describes the way employees show a logical and emotional commitment to their work, team, and organization, which in turn drives their discretionary effort. Costs of Employee Disengagement Actively disengaged employees are more likely to steal, miss work, and negatively influence other workers and cost the United States up to $550 billion annually in lost resources and productivity (8). -

Action to End Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation

ACTION TO END CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE AND EXPLOITATION Published by UNICEF Child Protection Section Programme Division 3 United Nations Plaza New York, NY 10017 Email: [email protected] Website: www.unicef.org © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) December 2020. Permission is required to reproduce any part of this publication. Permission will be freely granted to educational or non-profit organizations. For more information on usage rights, please contact: [email protected] Cover photo: © UNICEF/UNI303881/Zaidi Design and layout by Big Yellow Taxi, Inc. Suggested citation: United Nations Children’s Fund (2020) Action to end child sexual abuse and exploitation, UNICEF, New York This publication has been produced with financial support from the End Violence Fund. However, the opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the End Violence Fund. Click on section bars to navigate publication CONTENTS 1. Introduction ............................................3 6. Service delivery ...................................21 2. A Global Problem...................................5 7. Social & behavioural change ................27 3. Building on the evidence .................... 11 8. Gaps & challenges ...............................31 4. A Theory of Change ............................13 Endnotes .................................................32 5. Enabling National Environments ..........15 1 Ending Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation: A Review of the Evidence ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS -

Data Sheet: Oracle Recruiting Cloud

Oracle Recruiting Finding the best talent, hiring them quickly and onboarding them efficiently, can be difficult in today’s competitive environment. Oracle Recruiting (part of Oracle Cloud HCM) addresses these common challenges of recruiting and takes this process into the modern era by leveraging a data-driven approach and a mobile user interface (UI) to Key features source and engage both internal and external • Requisition management • Career page design templates candidates, and apply business insights across • Mobile-responsive UI all of HCM for better hiring decisions. • Extensible branding and multimedia support • Job search and discovery INNOVATIVE TECHNOLOGY TO KEEP CANDIDATES AT • Candidate pools THE CENTER OF THE RECRUITING PROCESS • Adaptive intelligence Savvy organizations use technology to stay ahead of the competition when it comes • Native recruiting to attracting and retaining top talent. HR leaders are being tasked with broadening • End-to-end sourcing, recruiting, their approach to Human Capital Management, incorporating concepts and practices and offers that were once the primary domain of marketing, legal, or chief executives. The • Unified architecture and tooling practice of HR is also transforming from being a mere cost center to a value • Multichannel sourcing generator, driving business growth through holistic talent development. HR is evolving to increasingly leverage technology to improve efficiency and provide • Conversational interactions via insight into an organization’s most valuable source of productivity. Organizations use digital assistant this insight to help leaders understand success parameters and their organization’s • Proven third-party extensions talent capabilities. • Advanced reporting and analytics Oracle Recruiting is a new recruiting solution delivered natively as part of Oracle • Unified self-service interface Cloud HCM. -

Leading Remote Teams Provided By: Taggart Insurance

Leading Remote Teams Provided by: Taggart Insurance This HR Toolkit is not intended to be exhaustive nor should any discussion or opinions be construed as legal advice. Readers should contact legal counsel for legal advice. © 2020 Zywave, Inc. All rights reserved. Leading Remote Teams | Provided by: Taggart Insurance Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................4 Remote Work Planning ................................................................................................5 Schedules .....................................................................................................5 Technology ....................................................................................................5 Employee Workstation ..................................................................................5 Policies ..........................................................................................................6 Interviewing and Onboarding .......................................................................6 Virtual Interviewing ................................................................6 Remote Onboarding ..............................................................7 Company Culture in the Remote Workplace ...............................................................9 What Is Company Culture? ..........................................................................9 Strong Company Culture.............................................................................. -

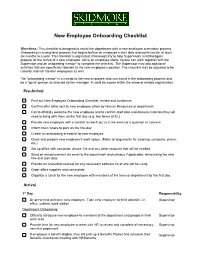

New Employee Onboarding Checklist

New Employee Onboarding Checklist Directions: This checklist is designed to assist the department with a new employee orientation process. Onboarding is a long-term process that begins before an employee’s start date and continues for at least six months to a year. This checklist is organized chronologically to help Supervisors and Managers prepare for the arrival of a new employee. Once an employee starts, he/she can work together with the Supervisor and an onboarding mentor* to complete the checklist. The Supervisor may add additional activities that are specifically relevant to the new employee’s position. The checklist may be adjusted to be used for internal transfer employees as well. *An "onboarding mentor" is a mentor to the new employee who can assist in the onboarding process and be a “go-to” person as directed by the manager. It could be a peer within the same or related organization. Pre-Arrival Print out New Employee Onboarding Checklist, review and customize Confirm offer letter sent to new employee either by Human Resources or department Call to officially welcome the new employee and to confirm start date and discuss materials they will need to bring with them on the first day (e.g. two forms of ID.) Provide new employee with a contact to reach out to in the event of a question or concern Inform them where to park on the first day Create an onboarding schedule for new employee Clean and prepare new employee's work space. (Make arrangements for cleaning, computer, phone, etc.) Set up office with computer, phone, file and any other resource that will be needed Send an announcement via email to the department and campus if applicable, announcing the new hire and start date Provide an instruction manual for any necessary software he or she will be using Order office supplies and name plate Organize a lunch for the new employee with members of the team or department for the first day Arrival 1st Day Responsibility Be present to welcome new employee. -

Position on Providing a Discrimination-Free Workplace

Position on Providing a Discrimination-Free Workplace Background A discrimination-free workplace is one in which employees are attracted, recruited, assigned to work, provided with training and development, promoted and remunerated on the basis of their capabilities. It signals that no distinction, exclusion or preference relating to an individual’s employment is made on grounds other than the ability or potential ability of an individual to meet required job needs. Discrimination-free means equal opportunity for all, irrespective of non-work-related personal characteristics. Further, it means actively advancing practices that promote equity by, for example, assuring inclusive selection criteria to more fully reach qualified persons. Discrimination in any form is harmful to society, individuals, and the conduct of business. By definition, discrimination prevents individuals from realizing their human rights and from fully and productively participating in society and/or business activity. The achievement of a prosperous society depends on all individuals being treated with dignity and respect. The achievement of sustainable business equally depends on individuals attaining employment in a workplace that values them and their unique qualities. Relevance As the largest and most broadly based healthcare company in the world, Johnson & Johnson has a considerable impact on the lives of many individuals whom we directly employ, and this includes providing a workplace in which employees can feel valued, safe and free from discrimination. We believe that fostering an open and inclusive work environment, in which we value contributions from individuals of all backgrounds and experiences, is not only the right thing to do, it gives us the best chance of being able to work together to advance our mission of profoundly changing the trajectory of health for humanity. -

A Researcher Speaks to Ombudsmen About Workplace Bullying LORALE IGH KEASHLY

Journal of the International Ombudsman Association Keashly Some Things You Need to Know but may have been Afraid to Ask: A Researcher Speaks to Ombudsmen about Workplace Bullying LORALE IGH KEASHLY ABSTRACT In the early 1990’s, I became interested in understand- ing persistent and enduring hostility at work. That Workplace bullying is repeated and prolonged hostile interest was spurred by a colleague’s experience at mistreatment of one or more people at work. It has the hands of her director. He yelled and screamed tremendous potential to escalate, drawing in others at her (and others), accusing her of not completing beyond the initial actor-target relationship. Its effects assignments, which she actually had. He lied about can be devastating and widespread individually, her and other subordinates. He would deliberately organizationally and beyond. It is fundamentally a avoid when staff needed his input and then berate systemic phenomenon grounded in the organization’s them for not consulting with him. At other times, he culture. In this article, I identify from my perspective was thoughtful, apologetic, and even constructive. My as a researcher and professional in this area current colleague felt like she was walking on eggshells, never thinking and research findings that may be useful for sure how he would be. Her coworkers had similar ombudsmen in their deliberations and investigations experiences and the group developed ways of coping as well as in their intervention and management of and handling it. For example, his secretary would these hostile behaviors and relationships. warn staff when it was not a good idea to speak with him. -

Mentor Onboarding Guide

MENTOR ONBOARDING GUIDE Everyone remembers how difficult the first few weeks on a new job can be. Those initial experiences went a long way in determining how quickly you became an effective, fully contributing member of our agency. Now, it is your turn to help ensure that our new employee’s first days and months on the job provide a successful launch to their career. You are responsible for helping the employee get settled into the agency, their workplace, and the local area. Being a mentor is not a substitute for the supervisor, but is someone who can answer the new employee’s questions about the work environment and the workplace culture in a positive and encouraging way. Your basic role is to meet with the new employee regularly and be available to answer questions, provide resources and insights about the agency. You will be their “go to” person and be available to help them find their way around at work. You can expect to serve as a mentor for around the first 3 months from the time they start with our agency. You are one of the keys to the success of the new employee during the onboarding process. WHY HAVE I BEEN SELECTED? You are an experienced employee and have demonstrated excellent performance and have good people skills. You have the demonstrated ability to build trust with the new employee, and are familiar with our high performance culture and agency mission and vision. You “know the ropes” and are an effective source of advice and encouragement. Selection Criteria Used Demonstrates high performance. -

Inequalities in Victimisation: Alcohol, Violence, and Anti-Social Behaviour

Inequalities in victimisation: alcohol, violence, and anti-social behaviour An Institute of Alcohol Studies report May 2020 Contents Executive summary 4 Introduction 5 Method 11 Results 18 Discussion 38 Conclusion 41 AN INSTITUTE OF ALCOHOL STUDIES REPORT PAGE 2 Inequalities in victimisation: alcohol, violence, and anti-social behaviour Author Lucy Bryant, Research and Policy Officer for the Institute of Alcohol Studies. Acknowledgements We are grateful to: Dr Carly Lightowlers, Professor Jonathan Shepherd, the team at the Office for National Statistics, the London School of Economics Methology Surgery, Aveek Bhattacharya, Katherine Severi, Dr Sadie Boniface, Habib Kadiri, Richard Fernandez, Dr Kieran Bunn, Sarah Schoenberger, and Emma Vince. The work was presented at KBS 2019, the 45th Annual Alcohol Epidemiology Symposium of the Kettil Bruun Society. For copyright of all statistical results in this paper, source: ONS. Image credit George-Standen - iStock About the Institute of Alcohol Studies IAS is an independent institute bringing together evidence, policy and practice from home and abroad to promote an informed debate on alcohol’s impact on society. Our purpose is to advance the use of the best available evidence in public policy discussions on alcohol. The IAS is a company limited by guarantee (no. 05661538) and a registered charity (no. 1112671). All Institute of Alcohol Studies reports are subject to peer review by at least two academic researchers that are experts in the field. Contact us Location: Alliance House, 12 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QS Telephone: 020 7222 4001 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @InstAlcStud Web: www.ias.org.uk AN INSTITUTE OF ALCOHOL STUDIES REPORT PAGE 3 Executive summary Introduction • The links between alcohol and violence, as well as alcohol and anti-social behaviour (ASB), are widely recognised. -

CRC/C/156 Convention on the Rights of the Child

United Nations CRC/C/156 Convention on the Distr.: General 10 September 2019 Rights of the Child Original: English Guidelines regarding the implementation of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography* * Adopted by the Committee at its eighty-first session (13–31 May 2019). GE.19-15447(E) CRC/C/156 Contents Page I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 A. Recent developments related to the sale and sexual exploitation of children ....................... 3 B. An increasing body of recommendations from various international stakeholders .............. 4 II. Objectives of the guidelines .......................................................................................................... 4 III. General measures of implementation ............................................................................................ 4 A. Legislation ............................................................................................................................ 5 B. Data collection ...................................................................................................................... 5 C. Comprehensive policy and strategy ...................................................................................... 6 D. Coordination, monitoring and evaluation ............................................................................ -

Elevating the Onboarding Experience

Elevating the Onboarding Experience A GOVERNANCE PROFESSIONALS’ GUIDE The Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) is grateful to the following members of the Governance Professionals Peer Learning Network who contributed to the development of this guide. Ruth Agi – Erie St. Clair Local Health Integration Network Kimberly Bougher – St. Thomas Elgin General Hospital Margaret Clark – Peterborough Regional Health Centre Terri-Lynn Cook – St. Joseph’s Health Care, London Sue Davey – Huron Perth Healthcare Alliance Patty Dimopoulos – Brockville General Hospital Danette Dutot – Hotel Dieu Grace Healthcare Cassa Easton – Grand River Hospital Corporation Joanne Hartnett – Queensway Carleton Hospital Loralee Heemskerk – Tillsonburg District Memorial Hospital Susan La Brie – Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care Sheila Mabee – Lennox and Addington County General Hospital Jennifer Matthews – The Ottawa Hospital Trish Matthews – Scarborough and Rouge Hospital Robin Moore – Ontario Shores Centre for Mental Health Sciences Julia Oosterman – Bluewater Health Lise Peterson – Erie Shores Healthcare Pam Porter – Ontario Shores Centre for Mental Health Sciences Wendy Sallows – Royal Victoria Regional Health Centre Katrina Santiago – Central Local Health Integration Network Anne Schnurr – South Bruce Grey Health Centre Kathy Vader – Pathways to Independence Elevating the Onboarding Experience: A Governance Professionals’ Guide The confidence of a new board member and the ability to engage and contribute meaningfully to the practice of good governance can be traced back to onboarding effectiveness combined with previous governance experience, sector knowledge, skills and expertise. A board orientation includes both content and process items which contribute to a new board member’s ability to effectively fulfill their fiduciary duties. Boards have different cultures and face different pressures and challenges so the approach to onboarding varies across organizations.