Verbal Abuse Toward Early Career Nurses and the Effect to Workforce Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engaging the Workforce Getting Past Once-And-Done Measurement Surveys to Achieve Always-On Listening and Meaningful Response

Engaging the workforce Getting past once-and-done measurement surveys to achieve always-on listening and meaningful response Deloitte Employee Engagement Perspectives Deloitte Employee Engagement Perspectives / Engaging the workforce What is employee engagement? Organizations are increasingly talking about engagement, but not everyone is defining and measuring it in the same way. Engagement typically refers to an employee’s job satisfaction, loyalty, and inclination to expend discretionary effort toward organizational goals.1 It predicts individual performance and operates at the most fundamental levels of the organization —individual and line—where the most meaningful impact can be made. Workplace culture is related, though operates on a different level. Culture is a system of values, beliefs, and behaviors that shape how real work gets done within an organization. It predicts company performance, and is shaped and cultivated at the most senior levels of the organization. 1 Deloitte Employee Engagement Perspectives / Engaging the workforce The vast majority of executives responding to our Global Human Capital Trends survey rated engagement as a priority for their companies. More than executives rated engagement as important or very important.2 8 in10 But company actions regarding engagement don’t always support that level of importance. Just 64% And of respondents say they are measuring employee one in five engagement once a year.3 (18%) said their companies don’t formally measure employee engagement at all.4 As the workforce and its expectations about work evolve rapidly, employers should start treating engagement as the business-critical issue it is. 1 Deloitte Employee Engagement Perspectives / Engaging the workforce Why does employee engagement matter ? Engagement is critical because it is directly linked to business outcomes. -

Employee Onboarding

Strategic Onboarding: The Effects on Productivity, Engagement, & Turnover By: Lisa Reed, MBA, SPHR Onboarding Defined A systematic and comprehensive approach to integrating a new employee with an employer and its culture, while also ensuring the employee is provided with the tools and information necessary to becoming a productive member of the team (1). How Important is Onboarding? 43% of employees state the opportunity for advancement was the key factor in deciding whether or not to stay with an organization, and the onboarding process, or lack thereof, was a main factor in determining advancement potential within a company (2). EMPLOYEE PRODUCTIVITY What is Employee Productivity? An assessment of the efficiency of a worker or group of workers, which is typically compared to averages, is referred to as employee productivity (3). Costs of Employee Unproductivity More than $37 billion dollars annually is spent by organizations in the US to keep unproductive employee in jobs they do not understand (4). What Effect Does Strategic Onboarding Have On Employee Productivity? Only 49% of new employees without formal onboarding meet their first performance milestone (5). In contrast, 77% of employees who are provided with a formal onboarding process meet first performance milestones (6). Employee performance can increase by 11% with an effective onboarding process, which can also be linked to a 20% increase in an employee’s discretionary effort (7). EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT What is Employee Engagement? Employee engagement describes the way employees show a logical and emotional commitment to their work, team, and organization, which in turn drives their discretionary effort. Costs of Employee Disengagement Actively disengaged employees are more likely to steal, miss work, and negatively influence other workers and cost the United States up to $550 billion annually in lost resources and productivity (8). -

Data Sheet: Oracle Recruiting Cloud

Oracle Recruiting Finding the best talent, hiring them quickly and onboarding them efficiently, can be difficult in today’s competitive environment. Oracle Recruiting (part of Oracle Cloud HCM) addresses these common challenges of recruiting and takes this process into the modern era by leveraging a data-driven approach and a mobile user interface (UI) to Key features source and engage both internal and external • Requisition management • Career page design templates candidates, and apply business insights across • Mobile-responsive UI all of HCM for better hiring decisions. • Extensible branding and multimedia support • Job search and discovery INNOVATIVE TECHNOLOGY TO KEEP CANDIDATES AT • Candidate pools THE CENTER OF THE RECRUITING PROCESS • Adaptive intelligence Savvy organizations use technology to stay ahead of the competition when it comes • Native recruiting to attracting and retaining top talent. HR leaders are being tasked with broadening • End-to-end sourcing, recruiting, their approach to Human Capital Management, incorporating concepts and practices and offers that were once the primary domain of marketing, legal, or chief executives. The • Unified architecture and tooling practice of HR is also transforming from being a mere cost center to a value • Multichannel sourcing generator, driving business growth through holistic talent development. HR is evolving to increasingly leverage technology to improve efficiency and provide • Conversational interactions via insight into an organization’s most valuable source of productivity. Organizations use digital assistant this insight to help leaders understand success parameters and their organization’s • Proven third-party extensions talent capabilities. • Advanced reporting and analytics Oracle Recruiting is a new recruiting solution delivered natively as part of Oracle • Unified self-service interface Cloud HCM. -

Leading Remote Teams Provided By: Taggart Insurance

Leading Remote Teams Provided by: Taggart Insurance This HR Toolkit is not intended to be exhaustive nor should any discussion or opinions be construed as legal advice. Readers should contact legal counsel for legal advice. © 2020 Zywave, Inc. All rights reserved. Leading Remote Teams | Provided by: Taggart Insurance Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................4 Remote Work Planning ................................................................................................5 Schedules .....................................................................................................5 Technology ....................................................................................................5 Employee Workstation ..................................................................................5 Policies ..........................................................................................................6 Interviewing and Onboarding .......................................................................6 Virtual Interviewing ................................................................6 Remote Onboarding ..............................................................7 Company Culture in the Remote Workplace ...............................................................9 What Is Company Culture? ..........................................................................9 Strong Company Culture.............................................................................. -

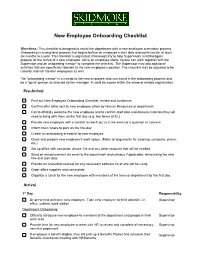

New Employee Onboarding Checklist

New Employee Onboarding Checklist Directions: This checklist is designed to assist the department with a new employee orientation process. Onboarding is a long-term process that begins before an employee’s start date and continues for at least six months to a year. This checklist is organized chronologically to help Supervisors and Managers prepare for the arrival of a new employee. Once an employee starts, he/she can work together with the Supervisor and an onboarding mentor* to complete the checklist. The Supervisor may add additional activities that are specifically relevant to the new employee’s position. The checklist may be adjusted to be used for internal transfer employees as well. *An "onboarding mentor" is a mentor to the new employee who can assist in the onboarding process and be a “go-to” person as directed by the manager. It could be a peer within the same or related organization. Pre-Arrival Print out New Employee Onboarding Checklist, review and customize Confirm offer letter sent to new employee either by Human Resources or department Call to officially welcome the new employee and to confirm start date and discuss materials they will need to bring with them on the first day (e.g. two forms of ID.) Provide new employee with a contact to reach out to in the event of a question or concern Inform them where to park on the first day Create an onboarding schedule for new employee Clean and prepare new employee's work space. (Make arrangements for cleaning, computer, phone, etc.) Set up office with computer, phone, file and any other resource that will be needed Send an announcement via email to the department and campus if applicable, announcing the new hire and start date Provide an instruction manual for any necessary software he or she will be using Order office supplies and name plate Organize a lunch for the new employee with members of the team or department for the first day Arrival 1st Day Responsibility Be present to welcome new employee. -

Employees' Reactions to Their Own Gossip About Highly

BITING THE HAND THAT FEEDS YOU: EMPLOYEES’ REACTIONS TO THEIR OWN GOSSIP ABOUT HIGHLY (UN)SUPPORTIVE SUPERVISORS By JULENA MARIE BONNER Bachelor of Arts in Business Management and Leadership Southern Virginia University Buena Vista, VA 2007 Master of Business Administration Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2012 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 2016 BITING THE HAND THAT FEEDS YOU: EMPLOYEES’ REACTIONS TO THEIR OWN GOSSIP ABOUT HIGHLY (UN)SUPPORTIVE SUPERVISORS Dissertation Approved: Dr. Rebecca L. Greenbaum Dissertation Adviser Dr. Debra L. Nelson Dr. Cynthia S. Wang Dr. Isaac J. Washburn ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The road to completing this degree and dissertation has been a long, bumpy one, with plenty of ups and downs. I wish to express my gratitude to those who have helped me along the way. Those who provided me with words of encouragement and support, those who talked me down from the ledge when the bumps seemed too daunting, and those who helped smooth the path by taking time to teach and guide me. I will forever be grateful for my family, friends, and the OSU faculty and doctoral students who provided me with endless amounts of support and guidance. I would like to especially acknowledge my dissertation chair, Rebecca Greenbaum, who has been a wonderful mentor and friend. I look up to her in so many ways, and am grateful for the time she has taken to help me grow and develop. I want to thank her for her patience, expertise, guidance, support, feedback, and encouragement over the years. -

Position on Providing a Discrimination-Free Workplace

Position on Providing a Discrimination-Free Workplace Background A discrimination-free workplace is one in which employees are attracted, recruited, assigned to work, provided with training and development, promoted and remunerated on the basis of their capabilities. It signals that no distinction, exclusion or preference relating to an individual’s employment is made on grounds other than the ability or potential ability of an individual to meet required job needs. Discrimination-free means equal opportunity for all, irrespective of non-work-related personal characteristics. Further, it means actively advancing practices that promote equity by, for example, assuring inclusive selection criteria to more fully reach qualified persons. Discrimination in any form is harmful to society, individuals, and the conduct of business. By definition, discrimination prevents individuals from realizing their human rights and from fully and productively participating in society and/or business activity. The achievement of a prosperous society depends on all individuals being treated with dignity and respect. The achievement of sustainable business equally depends on individuals attaining employment in a workplace that values them and their unique qualities. Relevance As the largest and most broadly based healthcare company in the world, Johnson & Johnson has a considerable impact on the lives of many individuals whom we directly employ, and this includes providing a workplace in which employees can feel valued, safe and free from discrimination. We believe that fostering an open and inclusive work environment, in which we value contributions from individuals of all backgrounds and experiences, is not only the right thing to do, it gives us the best chance of being able to work together to advance our mission of profoundly changing the trajectory of health for humanity. -

Extending Managerial Control Through Coercion and Internalisation in the Context of Workplace Bullying Amongst Nurses in Ireland

societies Article “It’s Not Us, It’s You!”: Extending Managerial Control through Coercion and Internalisation in the Context of Workplace Bullying amongst Nurses in Ireland Juliet McMahon * , Michelle O’Sullivan, Sarah MacCurtain, Caroline Murphy and Lorraine Ryan Department of Work & Employment Studies, University of Limerick, V94 T9PX Limerick, Ireland; [email protected] (M.O.); [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (L.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article investigates why workers submit to managerial bullying and, in doing so, we extend the growing research on managerial control and workplace bullying. We employ a labour process lens to explore the rationality of management both engaging in and perpetuating bullying. Labour process theory posits that employee submission to workplace bullying can be a valuable method of managerial control and this article examines this assertion. Based on the qualitative feedback in a large-scale survey of nurses in Ireland, we find that management reframed bullying complaints as deficiencies in the competency and citizenship of employees. Such reframing took place at various critical junctures such as when employees resisted extremely pressurized environments and when they resisted bullying behaviours. We find that such reframing succeeds in suppressing resistance and elicits compliance in achieving organisational objectives. We demonstrate how a pervasive bullying culture oriented towards expanding management control weakens an ethical Citation: McMahon, J.; O’Sullivan, climate conducive to collegiality and the exercise of voice, and strengthens a more instrumental M.; MacCurtain, S.; Murphy, C.; Ryan, climate. Whilst such a climate can have negative outcomes for individuals, it may achieve desired L. -

Mentor Onboarding Guide

MENTOR ONBOARDING GUIDE Everyone remembers how difficult the first few weeks on a new job can be. Those initial experiences went a long way in determining how quickly you became an effective, fully contributing member of our agency. Now, it is your turn to help ensure that our new employee’s first days and months on the job provide a successful launch to their career. You are responsible for helping the employee get settled into the agency, their workplace, and the local area. Being a mentor is not a substitute for the supervisor, but is someone who can answer the new employee’s questions about the work environment and the workplace culture in a positive and encouraging way. Your basic role is to meet with the new employee regularly and be available to answer questions, provide resources and insights about the agency. You will be their “go to” person and be available to help them find their way around at work. You can expect to serve as a mentor for around the first 3 months from the time they start with our agency. You are one of the keys to the success of the new employee during the onboarding process. WHY HAVE I BEEN SELECTED? You are an experienced employee and have demonstrated excellent performance and have good people skills. You have the demonstrated ability to build trust with the new employee, and are familiar with our high performance culture and agency mission and vision. You “know the ropes” and are an effective source of advice and encouragement. Selection Criteria Used Demonstrates high performance. -

Developing an Employee Engagement Strategy

SHRM FOUNdatION EXecutIve BRIefING DEVELOPING AN EMPLOYee ENGAGEMENT STRATEGY Sponsored by SurveyMonkey usiness leaders have long recognized that attracting and company profit, employee turnover and occurrence of safety Bretaining top talent is critical for organizational success. incidents.2 Given that engagement affects organizational Over the past two decades, organizations have increasingly outcomes that relate directly to the bottom line, companies focused on employee engagement as a way to maximize that ignore employee engagement risk putting themselves at the capabilities and talent of their human capital. This is a competitive disadvantage. not surprising, as the benefits of employee engagement for Though many organizations conduct engagement organizations are clear. A recent summary of engagement surveys, a survey alone will not increase employee research1 found that not only are engaged employees better engagement. To attain the best results, employers performers but engagement enhances employees’ job should create an overall engagement strategy that goes performance in unique ways. Additionally, high levels of beyond simply measuring engagement scores. Although engagement are related to important business outcomes, organizations are often highly proficient in collecting data, including customer satisfaction, employee productivity, many fail to interpret the information correctly and to create actionable recommendations for improving engagement.3 What Is Employee Engagement? Developing an engagement strategy helps avoid these pitfalls There are three parts to employee engagement: by describing what will happen after the survey is conducted. Physical. Employees exert high levels of energy to complete their work tasks. Emotional. Employees put their heart into their Implementing an Engagement Strategy job, have a strong involvement in their work and Depending on your organization’s staff size, target a sense of the significance of it, and feel inspired a limited number of lower-performing units to and challenged. -

Elevating the Onboarding Experience

Elevating the Onboarding Experience A GOVERNANCE PROFESSIONALS’ GUIDE The Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) is grateful to the following members of the Governance Professionals Peer Learning Network who contributed to the development of this guide. Ruth Agi – Erie St. Clair Local Health Integration Network Kimberly Bougher – St. Thomas Elgin General Hospital Margaret Clark – Peterborough Regional Health Centre Terri-Lynn Cook – St. Joseph’s Health Care, London Sue Davey – Huron Perth Healthcare Alliance Patty Dimopoulos – Brockville General Hospital Danette Dutot – Hotel Dieu Grace Healthcare Cassa Easton – Grand River Hospital Corporation Joanne Hartnett – Queensway Carleton Hospital Loralee Heemskerk – Tillsonburg District Memorial Hospital Susan La Brie – Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care Sheila Mabee – Lennox and Addington County General Hospital Jennifer Matthews – The Ottawa Hospital Trish Matthews – Scarborough and Rouge Hospital Robin Moore – Ontario Shores Centre for Mental Health Sciences Julia Oosterman – Bluewater Health Lise Peterson – Erie Shores Healthcare Pam Porter – Ontario Shores Centre for Mental Health Sciences Wendy Sallows – Royal Victoria Regional Health Centre Katrina Santiago – Central Local Health Integration Network Anne Schnurr – South Bruce Grey Health Centre Kathy Vader – Pathways to Independence Elevating the Onboarding Experience: A Governance Professionals’ Guide The confidence of a new board member and the ability to engage and contribute meaningfully to the practice of good governance can be traced back to onboarding effectiveness combined with previous governance experience, sector knowledge, skills and expertise. A board orientation includes both content and process items which contribute to a new board member’s ability to effectively fulfill their fiduciary duties. Boards have different cultures and face different pressures and challenges so the approach to onboarding varies across organizations. -

HR Recruiting and Onboarding Specialist

HR Recruiting and Onboarding Specialist Position Summary: As an HR Recruiting and Onboarding Specialist you will perform a variety of HR tasks including Full Lifecycle Recruiting, all facets of Onboarding, entering and maintaining accurate data in HR systems, creating employee communications, and Marketing. You will also serve as a back-up for Payroll, Reporting, Benefits, Worker’s Compensation, Event Planning and more. Primary Duties and Responsibilities: Full lifecycle recruiting: Including gaining an understand of recruiting needs, posting internally and to external job boards, organizing and filing applicant data, networking with schools, soliciting referrals, attending career fairs and other networking events as requested, leveraging social media, sourcing passive candidates, reviewing applications, screening candidates, coordinating phone calls, Skype, and in-person interviews, creating agendas, arranging travel and coordinating candidate reimbursement, ensuring all paperwork is collected, communicating with applicants throughout the recruiting process. Onboarding: Including initiating applicable background checks, and medical testing, entering into applicable HR systems, creating first day / week agendas, answering any questions the new hire has, coordinating with others to ensure a great onboarding experience, working with hiring managers to ensure they receive any support needed, following up with new hires post-start, and more. Communications: Which may include, editing job descriptions, drafting personnel announcements, creating company event flyers and meeting notices, updating organization charts. Ensuring internal electronic and physical bulletin boards are up-to-date. Participate in daily planning and prioritization of work and reporting of activities, as required. Serve as back-up for the HR Administration and Payroll Specialist. Other job duties, as assigned. Some travel, as needed.