Hemispheres Studies on Cultures and Societies Vol. 32

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Mosque Report

The American Mosque 2020: Growing and Evolving Report 1 of the US Mosque Survey 2020: Basic Characteristics of the American Mosque Dr. Ihsan Bagby Research Team Dr. Ihsan Bagby, Primary Investigator and Report Table of Contents Author Research Advisory Committee Dr. Ihsan Bagby, Associate Professor of Islamic Introduction ......................................................... 3 Studies, University of Kentucky Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research, ISPU Major Findings ..................................................... 4 Dr. Besheer Mohamed, Senior Researcher, Pew Research Center Dr. Scott Thumma, Professor of Sociology of Mosque Essential Statistics ................................ 7 Religion, Hartford Seminary Number of Mosques .............................................. 7 Dr. Shariq Siddiqui, Director, Muslim Philanthropy Initiative, Indiana University Location of Mosques ............................................. 8 Riad Ali, President and Founder, American Muslim Mosque Buildings .................................................. 9 Research and Data Center Dr. Zahid Bukhari, Director, ICNA Council for Social Year Mosque Moved to Its Present Location ........ 10 Justice City/Neighborhood Resistance to Mosque Development ....................................... 10 ISPU Publication Staff Mosque Concern for Security .............................. 11 Dalia Mogahed, Director of Research Erum Ikramullah, Research Project Manager Mosque Participants ......................................... 12 Katherine Coplen, Director of Communications -

New AFED Properties on the Horizon

Vol 39, No. 1 Rabi Al-Thani 1442, A.H. December, 2020 AFED Business Park Dar es Salaam Amira Apartments Dar es Salaam New AFED Properties Zahra Residency Madagascar on the Horizon Federation News • Conferences: Africa Federation, World Federation, Conseil Regional Des Khojas Shia Ithna-Asheri Jamates De L’ocean Indien. • Health: Understanding the Covid-19 Pandemic. • Opinion: Columns from Writers around the World • Qur’an Competition Az Zahra Bilal Centre Tanga • Jamaat Elections Jangid Plaza epitomizes the style and status of business in the Floor for Shopping Center most prestigious location in Dar Es Salaam with its elegant High Speed Internet access capability design and prominent position to the Oysterbay Area. Businesses gain maximum exposure through its strategic location Fully Controllable Air Conditioning in Each Floor on Ally Hassan Mwinyi Road and its close proximity to the CCTV cameras and access control, monitored from central commercial hub of Dar Es Salaam a prime location for security room world-class companies and brands. 24 Hour Security Amenities: Location: Main Road Ally Hassan Mwinyi Road and Junction of BOOK YOUR SPACE NOW Protea Apartment (Little Theater) Contact us at: Jangid Plaza Ltd. Retail outlets on the ground and mezzanine floor P.O.Box 22028, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. 2 Eight Floors of A-Class office Space, Offices ranging fom 109m Sales Hotline: +255 784 737-705, +255 786 286-200 2 to Over 1800m Email: shafi[email protected] Website: www.jangidplaza.co.tz Features: Electronic access cards for secured parking and tenants areas Drop off Area at Building Entrance Designated visitors parking 120 Covered Parking Spaces on Basement Levels Luxurious Interior Design of Ground Floor Lobby Using Marble and Granite Four (4) High Speed Lifts and Two (2) Escalators on Ground Floor for Shopping Center 3. -

Twitter Ban and the Challenges of Digital Democracy in Africa

A PUBLICATION OF CISLAC @cislacnigeria www.facebook.com/cislacnigeria website: www.cislacnigeria.net VOL. 16 No. 5, MAY 2021 Participants in a group photo at a 'One-day CSO-Executive-Legislative Roundtable to appraise the Protection of Civilians and Civilian Harm mitigation in Armed Conflict' organised by CISLAC in collaboration with Centre for Civilians in Conflict with support from European Union. Twitter Ban And The Challenges Of Digital Democracy In Africa By Auwal Ibrahim Musa (Rafsanjani) America (VOA) observes that in ParliamentWatch in Uganda; and Uganda, the website Yogera, or ShineYourEye in Nigeria. s the emergence of digital 'speak out', offers a platform for The 2020 virtual protest in media shapes Africans' way citizens to scrutinize government, Z a m b i a t o Aof life, worldview, civic complain about poor service or blow #ZimbabweanLivesMatter, exposed mobilisation, jobs and opportunities, the whistle on corruption; Kenya's the potential of social media to public perception and opinion of Mzalendo website styles itself as the empower dissenting voices. The governance, the digital democracy 'Eye on the Kenyan Parliament', impact of WhatsApp and Facebook in also evolves in gathering pace for profiling politicians, scrutinizing Gambia's elections has indicated average citizens to take an active role expenses and highlighting citizens' that even in rural areas with limited in public discourse. rights; People's Assembly and its connectivity, social media content In 2017 published report, Voice of sister site PMG in South Africa; Cont. on page 4 Senate Passes Nigeria Still Southwest Speakers Want Procurement of Experts Review Draft Policy on Civilians’ University Bill Dromes, Helicopters to tackle Insecurity Protection in Harmed Conflict - P. -

From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’S Popular Mobilisation Units

From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units By Inna Rudolf CONTACT DETAILS For questions, queries and additional copies of this report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS United Kingdom T. +44 20 7848 2098 E. [email protected] Twitter: @icsr_centre Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. © ICSR 2018 From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units Contents List of Key Terms and Actors 2 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 – The Birth and Institutionalisation of the PMU 11 Chapter 2 – Organisational Structure and Leading Formations of Key PMU Affiliates 15 The Usual Suspects 17 Badr and its Multi-vector Policy 17 The Taming of the “Special Groups” 18 Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq – Righteousness with Benefits? 18 Kata’ib Hezbollah and the Iranian Connection 19 Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada – Seeking Martyrdom in Syria? 20 Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba – a Hezbollah Wannabe? 21 Saraya al-Khorasani – Tehran’s Satellite in Iraq? 22 Kata’ib Tayyar al-Risali – Iraqi Loyalists with Sadrist Roots 23 Saraya al-Salam – How Rebellious are the Peace Brigades? 24 Hashd al-Marji‘i – the ‘Holy’ Mobilisation 24 Chapter 3 – Election Manoeuvring 27 Betting on the Hashd 29 Chapter 4 – Conclusion 33 1 From Battlefield to Ballot Box: Contextualising the Rise and Evolution of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units List of Key Terms and Actors AAH: -

House of Reps Order Paper 7 July , 2020

FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY (2019-2023) SECOND SESSION NO. 8 9 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 7 July, 2020 1. Prayers 2. National Pledge 3. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 4. Oaths 5. Messages from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 6. Messages from the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 7. Messages from Other Parliament(s) (if any) 8. Other Announcements (if any) 9. Petitions (if any) 10. Matters of Urgent Public Importance 11. Personal Explanation PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Federal Co-operative Colleges (Establishment) Bill, 2020 (HB. 913) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 2. Family Support Trust Fund Act (Repeal) Bill, 2020 (HB. 914) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 3. Nigerian Institute of Animal Science Act (Amendment) Bill, 2020 (HB. 915) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 4. Orthopaedic Hospitals Management Board Act (Amendment) Bill, 2020 (HB. 916) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 5. Tertiary Education Trust Fund (Establishment Etc.) Act (Amendment)) Bill, 2020 (HB.863) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 6. National Security Investment Bill, 2020 (HB. 917) (Hon. Oluwole Oke) – First Reading. 10. Tuesday, 7 July, 2020 No. 8 7. Chartered Institute of Information and Strategy Management (Establishment etc.) Bill, 2020 (HB. 918) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 8. Medical Negligence (Litigation) Bill, 2020 (HB. 919) (Hon. Oluwole Oke) – First Reading. 9. Limitation Periods (Freezing) Bill, 2020 (HB. 920) (Hon. Onofiok Luke) – First Reading. 10. National Water Resources Bill, 2020 (HB. 921) (Hon. Sada Soli Jiba) – First Reading. 11. Obafemi Awolowo University (Transitional Provisions) Act (Amendment) Bill, 2020 (HB.922) (Hon. -

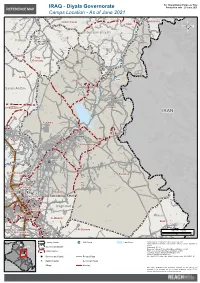

IRAQ - Diyala Governorate Production Date : 28 June 2021 REFERENCE MAP Camps Location - As of June 2021

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ - Diyala Governorate Production date : 28 June 2021 REFERENCE MAP Camps Location - As of June 2021 # # # # # # # # # # # # P! # # Qaryat Khashoga AsriyaAsriya al-Sutayihal-Sutayih # Big UboorUboor## #QalqanluQalqanlu BigBig Bayk Zadah Tilakoi PaykuliPaykuli# # # Kawta Sarkat BoyinBoyin Qaryat Khashoga# Big #Bayk Zadah Tilakoi GulaniGulani HamaHama # Zmnako Psht Qala Kawta Sarkat Samakah Village GarmiyanGarmiyan MalaMala OmarOmar MasoyMasoy BargachBargach BarkalBarkal CampeCampe Zmnako Psht Qala # Satayih Upper Hay Ashti Samakah Village QalqanluQalqanlu # # QalanderQalander# # MahmudMahmud # # Satayih Upper Hay Ashti TalTal RabeiaRabeia CollectiveCollective MasuiMasui HamaHama TilakoyTilakoy Pskan Khwarw SarshatSarshat UpperUpper TawanabalTawanabalGrdanaweGrdanawe # # # LittleLittle KoyikKoyik ChiyaChiya Pskan Khwarw # # # # AlwaAlwa PashaPasha TownTown # # #FarajFaraj #QalandarQalandar # MordinMordin FakhralFakhral # JamJam BoorBoor Charmic ZarenZaren # # Charmic # Satayih KurdamiriKurdamiri # NejalaNejala Satayih ShorawaShorawa ChalawChalaw DewanaDewana AzizAziz BagBag HasanHasan ParchunParchun FaqeFaqe MustafaMustafa # # Yousifiya # # # # # HamaiHamai Halabcha Hasan Shlal Yousifiya KaniKani ZhnanZhnan Hasan Shlal # AlbuAlbu MuhamadMuhamad Chamchamal RamazanRamazan MamkaMamka SulaimanSulaiman GorGor AspAsp # # # # KurdamirKurdamir # # AhmadAhmad ShalalShalal ZaglawaZaglawa Aghaja Mashad Ahmad OmarOmar AghaAgha # # Aghaja Mashad Ahmad TazadeTazade ImamImam Quli Matkan# (Aroba(Aroba TheThe DijlaDijla -

House of Representatives Federal Republic of Nigeria Order Paper

63 FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY (2019 – 2023) FIRST SESSION NO. 16 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday 23 July, 2019 1. Prayers 2. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Message from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 5. Message from the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 6. Other Announcements (if any) 7. Petitions (if any) 8. Matter(s) of Urgent Public Importance 9. Personal Explanation _______________________________________________________ PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.203) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 2. Nigerian Assets Management Agency (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.204) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 3. Securitization Bill, 2019 (HB.205) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 4. Payment Systems Management Bill, 2019 (HB. 206) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 5. Witness Protection Programme Bill, 2019 (HB. 207) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 6. Pension Reform Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.208) (Hon. Aishatu Jibril Dukku) – First Reading. 7. National Universities Commission Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.209) (Hon. Aishatu Jibril Dukku) – First Reading. 64 Tuesday 23 July, 2019 No. 16 8. National Universities Commission Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.209) (Hon. Aishatu Jibril Dukku) – First Reading. 9. Cerebrospinal Meningitis (Prevention, Control and Management) Bill, 2019 (HB.210) (Hon. Aishatu Jibril Dukku) – First Reading. 10. Companies and Allied Matters Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.211) (Hon. Yusuf Buba Yakub) – First Reading. 11. Federal University, Oye Ekiti, Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.212) (Hon. Adeyemi Adaramodu) – First Reading. 12. FCT Wider Area Planning and Development Commission Bill, 2019 (HB.213) (Hon. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 ‐ ‐ ‐ NEA PSHSS 14 001 Weekly Report 47–48 — July 7, 2015 Michael D. Danti, Cheikhmous Ali, Michel Maqdisi, Tate Paulette, Allison Cuneo, Kathryn Franklin, LeeAnn Barnes Gordon, Kyra Kaercher, and Erin Van Gessel Executive Summary During the reporting period in Syria, ISIL militants in the northern town of Manbij intercepted an individual(s) transporting Palmyrene funerary sculptures removed from tombs at the archaeological site and/or from the collections of the Tadmor Museum. ISIL sentenced this individual to public lashing and deliberately destroyed the sculptures. ISIL later released a video of these acts on social media sites. Media and social media sources variously identified this individual(s) as an antiquities trafficker(s), presumably unaffiliated with ISIL’s own‐ antiquities trafficking network, or an activist(s) attempting to save the sculptures. ISIL also released a video showing the mass execution of 25 SARG military personnel in the Palmyra Roman era Theater (probably built in the late 2nd–early 3rd Century CE and partially a modern reconstruction). This execution occurred May 27, 2015 and the video was released on July 4. The use of a well known heritage site as the backdrop for this horrific act has numerous ramifications regarding ISIL’s use of heritage in propaganda and future perceptions of this heritage site and its intangible associations. DGAM Daraa MuseumIn western Syria, ASOR CHI sources have reported damage to archaeological sites caused by intense military clashes in the area of Zabadani. In southern Syria, the reports that the suffered minor damage to the interior of the building and the exterior garden courtyard during military combat. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 31 January, 2012

FOURTH REPUBLIC 7TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION No. 109 351 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 31 January, 2012 1. Prayers 2. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) S. Petitions (if any) 6. Matter(s) of Urgent Public Importance 7. Personal Explanation PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Police Ombudsman (Establishment) Bill, 2011 (HB. 92) (Hon. Ndudi Godwin Elumelu) - First Reading. 2. Nigerian Infrastructure Development Bank Bill, 2011 (HB. 108) (Hon. 1m Akpan Udoka) - First Reading. 3. Witness Protection Programme Bill, 2011 (HB. 118) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) - First Reading. 4. Senior Citizens Center Bill, 2011 (HB. 119) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) - First Reading. S. Anti-Torture Bill, 2011 (HB. 120) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) - First Reading. 6. Nigerian Sports Dispute Resolution Center Bill, 2011 (HB. 121) tHon. Robinson Uwak) - First Reading. 7. Constitutionof the Federal Republic of Nigeria (Further Alteration) Bill, 2011 (HB. 123) (Hon. Fon lJeanyi Dike) - First Reading. 8. National Socio-Cultural Integration Bill, 2011 (HB. 124) (Hon. Fort lJeanyi Dike) - First Reading. 9. Constitutionof the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Further Amendment) Bill, 2011 (HB. 151) (Hon. Leo Okuweh Ogor) - First Reading. PRJNTED BY NA TlONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 352 Tuesday, 31 January. 2012 No. 109 PRESENTATION OF REPORTS 1. Committee of Federal Capital Territory: Hon. Emmanuel Jime: "That this House do receive the Report of the Committee on Federal Capital Territory on the Urgent Need to Construct Pedestrian Bridges along the Nnamdi Azikiwe By-Pass, Abuja" (HR. 83/2011) (Referred: 3011112011). 2. Committee of Federal Capital Territory: Hon. Emmanuel Jime: "That this House do receive the Report of the Committee on Federal Capital Territory Report on the Reactivation of the Abuja Rail Project" (HR. -

Mea Risk's Nigeria Weekly Threat

Politics/Social 3 MEA RISK’S Economic Issues 8 Security Issues 12 NIGERIA WEEKLY THREAT & STABILITY ASSESSMENT 31 OCTOBER TO 6 NOVEMBER 2016 HIGHLIGHTS For the period of 31 October to 6 November 2016, there were 74 critical incidents in Nigeria, resulting in at least 111 recorded deaths, 79 wounded, and Nigeria MEA Risk index 105 arrests. The highest share of incidents fell in the criminality category, which gathered over 32% of the incident pool during the week, followed by nearly 19% by the Human & Social Crises category. On the political front, Nigeria is confronted with multiple challenges, dominated this past week by the rejection by many militant groups in the Niger Delta of the ongoing negotiations between the Federal Government and political representatives of the oil producing regions. Militants involved in attacking oil sites and facilities, mainly pipeline, as well as civil organizations active in oil producing regions rejected the talks and refuse to endorse the negotiators selected to represent them. Also on the political front, the Federal Government has been facing growing opposition to its request to obtain a financial bailout from the IMF and the World Bank valued at nearly $30 billion. Not only the international donors insist that Nigeria undergoes a substantial structural adjustments that will inevitably lead to a major austerity plan, but the Nigerian assembly also rejected President Buhari’s request stating precisely that the impact of such a loan program will be devastating to the population. On the security front, Nigeria continues to be confronted with severe security problems. Despite the Nigerian military often insisting that it won the war against Boko Haram, there have persistent attacks from Boko Haram militants in the northeast, with daring incidents this week in Malam Fatori and in Talala and Ajigin, in the southern part of Borno State, resulting in scores of dead. -

Maley-Hazaras-4.3.20

4 March 2020 Professor William Maley, AM FASSA Professor of Diplomacy Asia Pacific College of Diplomacy Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs 130 Garran Road Acton ACT 2601 Australia On the Return of Hazaras to Afghanistan 1. I have been asked to provide an expert opinion on the safety of return to Afghanistan, and specifically to Kabul, Mazar-e Sharif, and Jaghori, for members of the Hazara minority. I am Professor of Diplomacy at the Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy at The Australian National University. I have published extensively on Afghan politics for over three decades, and am author of Rescuing Afghanistan (London: Hurst & Co., 2006); The Afghanistan Wars (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, 2009); What is a Refugee? (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); and Transition in Afghanistan: Hope, Despair and the Limits of Statebuilding (New York: Routledge, 2018). I have also written studies of The Foreign Policy of the Taliban (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2000) and Transitioning from military interventions to long-term counter-terrorism policy: The case of Afghanistan (2001-2016) (The Hague: The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2016); co-authored Regime Change in Afghanistan: Foreign Intervention and the Politics of Legitimacy (Boulder: Westview Press, 1991); Political Order in Post-Communist Afghanistan (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1992); and Afghanistan: Politics and Economics in a Globalising State (London: Routledge, 2020); edited Fundamentalism Reborn? Afghanistan and the Taliban (New York: New York University Press, 1998, 2001); and co-edited The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989); Reconstructing Afghanistan: Civil-military experiences in comparative perspective (New York: Routledge, 2015); and Afghanistan – Challenges and Prospects (New York: Routledge, 2018), I authored the entry on Hazaras in John L. -

Walk to Jerusalem Spring Week 5 We Had Another Great Week This Week

Walk to Jerusalem Spring Week 5 We had another great week this week. We had 53 participants and walked 1072.5 miles! The map below shows our progress through the end of week five (purple line). At the end of week four we had arrived at Zahedan, Iran, just over the border from Pakistan. On Monday, March 1, we proceeded to trek across Iran, hoping to arrive in Iraq by Sunday. I had no idea when I planned this tour last November that the Pope would be in Iraq when we arrived, nor was I certain we would reach Iraq in time to see him in person but we did! A note about Persians versus Arabs: Iranians view themselves as Persian, not Arabs. Persia at one point was one of the greatest empires of all time (see map on page 2). From this great culture we gained beautiful art seen in the masterful woven Persian carpets, melodic poetic verse, and modern algebra. It is referred to as an “ancient” empire, but, in fact, some Persian practices, such as equal rights for men and women and the abolishment of slavery, were way ahead of their time. The Persian Solar calendar is one of the world’s most accurate calendar systems. Persians come from Iran while Arabs come from the Arabia Peninsula. The fall Persia’s great dynasty to Islamic control occurred from 633-656 AD. Since that time surrounding Arab nations have forced the former power to repeatedly restructure, changing former Persia into present day Iran. But with history and culture this rich, it is to no surprise that Persians want to be distinguished from others including their Arab neighbors.