Hindustani Vocal Performance; an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For Component 3: Appraising)

Anoushka Shankar: Breathing Under Water – ‘Burn’, ‘Breathing Under Water’ and ‘Easy’ (For component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances The composer Anoushka Shankar was born in 1981, in London, and is the daughter of the famous sitar player Ravi Shankar. She was brought up in London, Delhi and California, where she attended high school. She studied sitar with her father from the age of 7, began playing tampura in his concerts at 10, and gave her first solo sitar performances at 13. She signed her first recording contract at 16 and her first three album releases were of Indian Classical performances. Her first cross-over/fusion album – Rise – was released in 2005 and was nominated for a Grammy, in the Contemporary World Music category. Her albums since Breathing Under Water have continued to explore the connections between Indian music and other styles. She has collaborated with some major artists – Sting, Nithin Sawhney, Joshua Bell and George Harrison, as well as with her father, Ravi Shankar, and her half-sister, Norah Jones. She has also performed around the world as a Classical sitar player – playing her father’s sitar concertos with major orchestras. The piece Breathing Under Water was Anoushka Shankar’s fifth album, and her second of original fusion music. Her main collaborator was Utkarsha (Karsh) Kale, an Indian musician and composer and co-founder of Tabla Beat Science – an Indian band exploring ambient, drum & bass and electronica in a Hindustani music setting. Kale contributes dance music textures and technical expertise, as well as playing tabla, drums and guitar on the album. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Hindustani Classic Music

HINDUSTANI CLASSIC MUSIC: Junior Grade or Prathamik : Syllabus : No theory exam in this grade Swarajnana Talajnana essential Ragajnana Practicals: 1. Beginning of swarabyasa - in three layas 2. 2 Swaramalikas 5 Lakshnageete Chotakyal Alap - 4 ragas Than - 4 Drupad - should be practiced 3. Bhajan - Vachana - Dasapadas 4. Theental, Dadara, Ektal (Dhruth), Chontal, Juptal, Kheruva Talu - Sam-Pet-Husi-Matras - should practice Tekav. 5. Swarajnana 6. Knowledge of the words - nada, shruthi, Aroha, Avaroha, Vadi - Samvedi, Komal - Theevra - Shuddha - Sasthak - Ganasamay - Thaat - Varjya. 7. Swaralipi - should be learnt. Senior Grade: (Madhyamik) Syllabus : Theory: 1. Paribhashika words 2. Sound & place of emergence of sound 3. The practice of different ragas out of “thaat” - based on Pandith Venkatamukhi Mela System 4. To practice ragalaskhanas of different ragas 5. Different Talas - 9 (Trital, Dadra, Jup, Kherva, Chantal, Tilawad, Roopak, Damar, Deepchandi) explanation of talas with Tekas. 6. Chotakhyal, Badakhyal, Bhajan, Tumari, Geethprakaras - Lakshanas. 7. Life history of Jayadev, Sarangdev, Surdas, Purandaradas, Tansen, Akkamahadevi, Sadarang, Kabeer, Meera, Haridas. 8. Knowledge of musical instrument Practicals: 1. Among 20 ragas - Chotakhyal in each 2. Badakhyal - for 10 ragas (Bhoopali, Yamani, Bheempalas, Bageshree, Malkonnse, Alhaiah Bilawal, Bahar, Kedar, Poorvi, Shankara. 3. Learn to sing one drupad in Tay, Dugun & Changun - one Damargeete. VIDHWAN PROFICIENCY Syllabus: Theory 1. Paribhashika Shabdas. 2. 7 types of Talas - their parts (angas) 3. Tabala bol - Tala Jnana, Vilambitha Ektal, Jumra, Adachontal, Savari, Panjabi, Tappa. 4. Raga lakshanas of Bhairav, Shuddha Sarang, Peelu, Multhani, Sindura, Adanna, Jogiya, Hamsadhwani, Gandamalhara, Ragashree, Darbari, Kannada, Basanthi, Ahirbhairav, Todi etc., Alap, Swaravisthara, Sama Prakruthi, Ragas criticism, Gana samay - should be known. -

Analyzing the Melodic Structure of a Raga-Based Song

Georgian Electronic Scientific Journal: Musicology and Cultural Science 2009 | No.2(4) A Statistical Analysis Of A Raga-Based Song Soubhik Chakraborty1*, Ripunjai Kumar Shukla2, Kolla Krishnapriya3, Loveleen4, Shivee Chauhan5, Mona Kumari6, Sandeep Singh Solanki7 1, 2Department of Applied Mathematics, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India 3-7Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India * email: [email protected] Abstract The origins of Indian classical music lie in the cultural and spiritual values of India and go back to the Vedic Age. The art of music was, and still is, regarded as both holy and heavenly giving not only aesthetic pleasure but also inducing a joyful religious discipline. Emotion and devotion are the essential characteristics of Indian music from the aesthetic side. From the technical perspective, we talk about melody and rhythm. A raga, the nucleus of Indian classical music, may be defined as a melodic structure with fixed notes and a set of rules characterizing a certain mood conveyed by performance.. The strength of raga-based songs, although they generally do not quite maintain the raga correctly, in promoting Indian classical music among laymen cannot be thrown away. The present paper analyzes an old and popular playback song based on the raga Bhairavi using a statistical approach, thereby extending our previous work from pure classical music to a semi-classical paradigm. The analysis consists of forming melody groups of notes and measuring the significance of these groups and segments, analysis of lengths of melody groups, comparing melody groups over similarity etc. Finally, the paper raises the question “What % of a raga is contained in a song?” as an open research problem demanding an in-depth statistical investigation. -

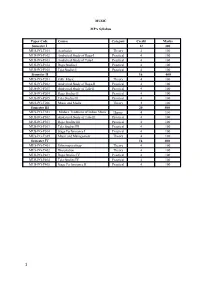

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men

Volume 64, Issue 1, 2020 Journal of Scientific Research Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men Samarpita Chatterjee (Mukherjee) 1, and Roan Mukherjee2* 1 Department of Hindustani Classical Music (Vocal), Sangit-Bhavana, Visva-Bharati (A Central University), Santiniketan, Birbhum-731235,West Bengal, India 2 Department of Human Physiology, Hazaribag College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Demotand, Hazaribag 825301, Jharkhand, India. [email protected] Abstract Several studies have indicated that music therapy may affect I. INTRODUCTION cardiovascular health; in particular, it may bring positive changes Music may be regarded as the projection of ideas as well as in blood pressure levels and heart rate, thereby improving the emotions through significant sounds produced by an instrument, overall quality of life. Hence, to regulate blood pressure, music voices, or both by taking into consideration different elements of therapy may be regarded as a significant complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). The respiratory rate, if maintained melody, rhythm, and harmony. Music plays an important role in within the normal range, may promote good cardiac health. The everyone’s life. Music has the power to make one experience aim of the present study was to evaluate the changes in blood harmony, emotional ecstasy, spiritual uplifting, positive pressure, pulse rate and respiratory rate in healthy and disease-free behavioral changes, and absolute tranquility. The annoyance in males (age 50-60 years), at the completion of 30 days of music life may increase in lack of melody and harmony. -

Ragang Based Raga Identification System

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 16, Issue 3 (Sep. - Oct. 2013), PP 83-85 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org Ragang based Raga Identification system Awadhesh Pratap Singh Tomer Assistant Professor (Music-vocal), Department of Music Dr. H. S. G. Central University Sagar M.P. Gopal Sangeet Mahavidhyalaya Mahaveer Chowk Bina Distt. Sagar (M.P.) 470113 Abstract: The paper describes the importance of Ragang in the Raga classification system and its utility as being unique musical patterns; in raga identification. The idea behind the paper is to reinvestigate Ragang with a prospective to use it in digital classification and identification system. Previous works in this field are based on Swara sequence and patterns, Pakad and basic structure of Raga individually. To my best knowledge previous works doesn’t deal with the Ragang Patterns for identification and thus the paper approaches Raga identification with a Ragang (musical pattern group) base model. This work also reviews the Thaat-Raagang classification system. This describes scope in application for Automatic digital teaching of classical music by software program to analyze music (Classical vocal and instrumental). The Raag classification should be flawless and logically perfect for best ever results. Key words: Aadhar shadaj, Ati Komal Gandhar , Bahar, Bhairav, Dhanashri, Dhaivat, Gamak, Gandhar, Gitkarri, Graam, Jati Gayan, Kafi, Kanada, Kann, Komal Rishabh , Madhyam, Malhar, Meed, Nishad, Raga, Ragang, Ragini, Rishabh, Saarang, Saptak, Shruti, Shrutiantra, Swaras, Swar Prastar, Thaat, Tivra swar, UpRag, Vikrat Swar A Raga is a tonal frame work for composition and improvisation. It embodies a unique musical idea.(Balle and Joshi 2009, 1) Ragang is included in 10 point Raga classification of Saarang Dev, With Graam Raga, UpRaga and more. -

108 Melodies

SRI SRI HARINAM SANKIRTAN - l08 MELODIES - INDEX CONTENTS PAGE CONTENTS PAGE Preface 1-2 Samant Sarang 37 Indian Classical Music Theory 3-13 Kurubh 38 Harinam Phylosphy & Development 14-15 Devagiri 39 FIRST PRAHAR RAGAS (6 A.M. to 9 A.M.) THIRD PRAHAR RAGAS (12 P.M. to 3 P.M.) Vairav 16 Gor Sarang 40 Bengal Valrav 17 Bhimpalasi 4 1 Ramkal~ 18 Piloo 42 B~bhas 19 Multani 43 Jog~a 20 Dhani 44 Tori 21 Triveni 45 Jaidev 22 Palasi 46 Morning Keertan 23 Hanskinkini 47 Prabhat Bhairav 24 FOURTH PKAHAR RAGAS (3 P.M. to 6 P.M.) Gunkali 25 Kalmgara 26 Traditional Keertan of Bengal 48-49 Dhanasari 50 SECOND PRAHAR RAGAS (9 A.M. to 12 P.M.) Manohar 5 1 Deva Gandhar 27 Ragasri 52 Bha~ravi 28 Puravi 53 M~shraBhairav~ 29 Malsri 54 Asavar~ 30 Malvi 55 JonPurl 3 1 Sr~tank 56 Durga (Bilawal That) 32 Hans Narayani 57 Gandhari 33 FIFTH PRAHAR RAGAS (6 P.M. to 9 P.M.) Mwa Bilawal 34 Bilawal 35 Yaman 58 Brindawani Sarang 36 Yaman Kalyan 59 Hem Kalyan 60 Purw Kalyan 61 Hindol Bahar 94 Bhupah 62 Arana Bahar 95 Pur~a 63 Kedar 64 SEVENTH PRAHAR RAGAS (12 A.M. to 3 A.M.) Jaldhar Kedar 65 Malgunj~ 96 Marwa 66 Darbar~Kanra 97 Chhaya 67 Basant Bahar 98 Khamaj 68 Deepak 99 Narayani 69 Basant 100 Durga (Khamaj Thhat) 70 Gaur~ 101 T~lakKarnod 71 Ch~traGaur~ 102 H~ndol 72 Shivaranjini 103 M~sraKhamaj 73 Ja~tsr~ 104 Nata 74 Dhawalsr~ 105 Ham~r 75 Paraj 106 Mall Gaura 107 SIXTH PRAHAR RAGAS (9Y.M. -

RAAG : YAMAN ( KALYAN ) AAROH : Sa Re Ga Ma' Pa Dha Ni Sa

SITAR – Raga Yaman Kalyan - Page 1 Get DVD to view how to play (delivered to your home) http://www.sharda.org/getDVD.htm RAAG : YAMAN ( KALYAN ) AAROH : Sa Re Ga Ma’ Pa Dha Ni Sa . AVROH : Sa . Ni Dha Pa Ma’ Ga Re Sa PAKAD : .Ni Re Ga Re Sa , Pa Ma’ Ga Re Sa , Ma’ Dha Ni Sa . , Ni Dha Pa , Pa Ma’ Ga Re , .Ni Re Sa STHAI : 3 X 2 0 GaGa | Re SaSa Ni Re | Ga Ga Ga ReRe | Ga Ma’Ma’ Pa Ma’ | Ga Re Sa Dir | Da Dir Da Ra | Da Da Ra Dir | Da Dir Da Ra | Da Da Ra ANTARA : 3 X 2 GaGa | Ma’ DhaDha Ni Re . | Ga . Re .Re . Sa . Ni | Dha PaPa Ma’ Ga | Dir | Da Dir Da Ra | Da Dir Da Ra | Da Dir Da Ra | 0 | Ga Re Sa | Da Da Ra TODE : X 1. .NiRe Ga.Ni ReGa .NiRe | ReGa Ma’Re GaMa’ ReGa | GaMa’ PaGa Ma’Pa GaMa’ | Ma’Pa DhaMa’ PaDha Ma’Pa | PaDha NiPa DhaNi PaDha | DhaNi Re .Dha NiRe . DhaNi | NiRe . Ga .Ni Re .Ga . NiRe . | Ga .Re . Sa .- Re .Sa . Ni- | Sa .Ni Dha- NiDha Pa- | DhaPa Ma’- PaMa’ Ga- | Ma’Ga Re- GaRe Sa- | .NiRe Ga.Ni ReGa .NiRe | X www.sharda.org – Learn Indian Music conveniently at your home SITAR – Raga Yaman Kalyan - Page 2 2. SaSa SaSa –Sa . NiSa . | Sa .Ni DhaPa Ma’Ga ReSa | SaSa SaSa -Sa . NiSa . | Sa .Ni DhaPa Ma’Ga ReSa | SaSa SaSa -Sa . NiSa . | Sa .Ni DhaPa Ma’Ga ReSa | .NiRe GaRe Ga .NiRe | GaRe Ga .NiRe GaRe | X 3. -

Indo-Caribbean "Local Classical Music"

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2000 The Construction of a Diasporic Tradition: Indo-Caribbean "Local Classical Music" Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/335 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] VOL. 44, NO. 1 ETHNOMUSICOLOGY WINTER 2000 The Construction of a Diasporic Tradition: Indo-Caribbean "Local Classical Music" PETER MANUEL / John Jay College and City University of New York Graduate Center You take a capsule from India leave it here for a hundred years, and this is what you get. Mangal Patasar n recent years the study of diaspora cultures, and of the role of music therein, has acquired a fresh salience, in accordance with the contem- porary intensification of mass migration and globalization in general. While current scholarship reflects a greater interest in hybridity and syncretism than in retentions, the study of neo-traditional arts in diasporic societies may still provide significant insights into the dynamics of cultural change. In this article I explore such dynamics as operant in a unique and sophisticated music genre of East Indians in the Caribbean.1 This genre, called "tan-sing- ing," has largely resisted syncretism and creolization, while at the same time coming to differ dramatically from its musical ancestors in India. Although idiosyncratically shaped by the specific circumstances of the Indo-Caribbean diaspora, tan-singing has evolved as an endogenous product of a particu- lar configuration of Indian cultural sources and influences.