Megac2b2-Iii-9-Karl-Marx-Friedrich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Communist Manifesto

The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide These notes are designed to help new comrades to understand some of the basic ideas of Marxism and how they relate to the politics of the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty (AWL). More experienced comrades leading the educationals can use the tutor notes to expand on certain key ideas and to direct comrades to other reading. Paul Hampton September 2006 1 The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide Contents Background to the Manifesto 3 Questions 5 Further reading 6 Title, preface, preamble 7 I: Bourgeois and Proletarians 9 II: Proletarians and Communists 19 III: Socialist and Communist Literature 27 IV: Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties 32 Glossary 35 2 Background to the Manifesto The text Karl Marx wrote the Manifesto of the Communist Party in German. It was first published in February 1848. It has sometimes been misdated 1847, including in Marx and Engels’ own writings, by Kautsky, Lenin and others. The standard English translation was done by Samuel Moore in 1888 and authorised by Frederick Engels. It can be downloaded from the Marxist Internet Archive http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/index.htm There are scores of other editions by different publishers and with other translations. Between 1848 and 1918, the Manifesto was published in more than 35 languages, in some 544 editions, (Beamish 1998 p.233) The text is also in the Marx and Engels Collected Works (MECW), Volume 6, along with other important articles, drafts and reports from the time. http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/cw/volume06/index.htm The context The Communist Manifesto was written for and published by the Communist League, an organisation founded less than a year before it was written. -

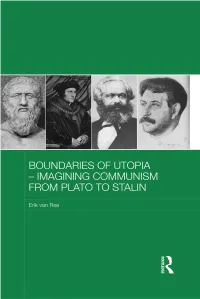

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin The idea that socialism could be established in a single country was adopted as an official doctrine by the Soviet Union in 1925, Stalin and Bukharin being the main formulators of the policy. Before this there had been much debate as to whether the only way to secure socialism would be as a result of socialist revolution on a much broader scale, across all Europe or wider still. This book traces the development of ideas about communist utopia from Plato onwards, paying particular attention to debates about universalist ideology versus the possibility for ‘socialism in one country’. The book argues that although the prevailing view is that ‘socialism in one country’ was a sharp break from a long tradition that tended to view socialism as only possible if universal, in fact the territorially confined socialist project had long roots, including in the writings of Marx and Engels. Erik van Ree is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of European Studies at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series 1 Liberal Nationalism in 7 The Telengits of Central Europe Southern Siberia Stefan Auer Landscape, religion and knowledge in motion 2 Civil-Military Relations in Agnieszka Halemba Russia and Eastern Europe David J. Betz 8 The Development of Capitalism in Russia 3 The Extreme Nationalist Simon Clarke Threat in Russia The growing influence of 9 Russian Television Today Western Rightist ideas Primetime drama and comedy Thomas Parland -

The Democratic Idiom: Languages of Democracy in the Chartist Movement*

The Democratic Idiom: Languages of Democracy in the Chartist Movement* Peter J. Gurney University of Essex The Journal of Modern History 86 (September 2014): 000-000 © 2014 by The University of Chicago. 0022-2801/2014/8603-0003$10.00 All rights reserved. I ever loved freedom, and its inevitable consequences, – and not only for what it will fetch, but the holy principle; – a democrat in my Sunday School, everywhere.1 I At Sheffield in late June 1842 a crowd of perhaps 50,000 mourners attended the public funeral of the twenty-seven year old Chartist militant Samuel Holberry, who had died of tuberculosis in a squalid cell at York Castle, after serving two years of a four-year sentence for his alleged involvement in an armed uprising. The immense crowd wept as George Julian Harney delivered a moving graveside oration. Harney praised the moral and intellectual qualities of this “heroic patriot,” sacrificed for “the cause of freedom” after being betrayed for “filthy lucre” by “rotten- hearted villains,” tools of “base employers – the oppressors that have pursued him to his grave.” “Tyrants,” Harney went on, were making determined attempts to “crush liberty; and by torture, chains, and death, to prevent the assertion of the rights of man....and arrest the progress of democracy,” but these “puny Canutes” were bound to be swept aside by “the ocean of intellect.” Harney reassured listeners that although Holberry‟s life had been snuffed out by a corrupt state, his faith lived on and the glories of an Alexander or a Napoleon would eventually pale into insignificance alongside “the honest, virtuous fame of this son of toil.” Samuel Parkes also spoke and recommended that they should not rest until “by every legal and constitutional means you have made the Charter the law of the land, and thereby proclaimed the physical, moral and political freedom of the universal family of man!” The crowd pressed forward as the “splendid oak coffin” provided by Holberry‟s supporters was lowered into the grave. -

Hörmann, Raphael (2007) Authoring the Revolution, 1819- 1848/49: Radical German and English Literature and the Shift from Political to Social Revolution

Hörmann, Raphael (2007) Authoring the revolution, 1819- 1848/49: radical German and English literature and the shift from political to social revolution. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1774/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] University of Glasgow Faculty of Arts PhD-Thesis in Comparative Literature Authoring the Revolution, 1819-1848/49: Radical German and English Literature and the Shift from Political to Social Revolution Submitted by Raphael HoUrmann @ Raphael H6nnann 2007 Acknowledgments I like to thank the various people and agenciesthat have provided vital help during various stages of this research project. First of all, I am greatly thankful to my supervisors, Professor Mark Ward and Dr. Laura Martin. Laura's pragmatic and practical advice and assistanceproved very helpful for overcomingall major obstacles in the course of my PhD studies at the University of Glasgow. Mark has not only been a tireless proof-reader at various stagesof the thesis, but his great enthusiasm with which he supported my project has been a continuous source of inspiration and encouragement throughout the writing and revising process. -

Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848,” for “Music and Revolution,” Concert and Lecture Series

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 5-2-1998 “Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848,” for “Music and Revolution,” concert and lecture series David B. Dennis Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Author Manuscript This is a pre-publication author manuscript of the final, published article. Recommended Citation Dennis, David B.. “Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848,” for “Music and Revolution,” concert and lecture series. The American Bach Project and supported by the Wisconsin Humanities Council as part of the State of Wisconsin Sesquicentennial Observances, All Saints Cathedral, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, , : , 1998. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © David B. Dennis 1998 “Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848” David B. Dennis Paper for “Music and Revolution,” concert and lecture series arranged by The American Bach Project and supported by the Wisconsin Humanities Council as part of the State of Wisconsin Sesquicentennial Observances, All Saints Cathedral Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2 May 1998. 1 Let me open by thanking Alexander Platt and Joan Parsley of Ensemble Musical Offering, for inviting me to speak with you tonight. -

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow By Thomas Wentworth Higginson HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW CHAPTER I LONGFELLOW AS A CLASSIC THE death of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow made the first breach in that well- known group of poets which adorned Boston and its vicinity so long. The first to go was also the most widely famous. Emerson reached greater depths of thought; Whittier touched the problems of the nation’s life more deeply; Holmes came personally more before the public; Lowell was more brilliant and varied; but, taking the English-speaking world at large, it was Longfellow whose fame overshadowed all the others; he was also better known and more translated upon the continent of Europe than all the rest put together, and, indeed, than any other contemporary poet of the English-speaking race, at least if bibliographies afford any test. Add to this that his place of residence was so accessible and so historic, his personal demeanor so kindly, his life so open and transparent, that everything really conspired to give him the highest accessible degree of contemporary fame. There was no literary laurel that was not his, and he resolutely declined all other laurels; he had wealth and ease, children and grandchildren, health and a stainless conscience; he had also, in a peculiar degree, the blessings that belong to Shakespeare’s estimate of old age,—“honor, love, obedience, troops of friends.” Except for two great domestic bereavements, his life would have been one of absolutely unbroken sunshine; in his whole career he never encountered any serious rebuff, while such were his personal modesty and kindliness that no one could long regard him with envy or antagonism. -

Popular Political Oratory and Itinerant Lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the Age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa M

Popular political oratory and itinerant lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa Martin This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of York Department of History January 2010 ABSTRACT Itinerant lecturers declaiming upon free trade, Chartism, temperance, or anti- slavery could be heard in market places and halls across the country during the years 1837- 60. The power of the spoken word was such that all major pressure groups employed lecturers and sent them on extensive tours. Print historians tend to overplay the importance of newspapers and tracts in disseminating political ideas and forming public opinion. This thesis demonstrates the importance of older, traditional forms of communication. Inert printed pages were no match for charismatic oratory. Combining personal magnetism, drama and immediacy, the itinerant lecturer was the most effective medium through which to reach those with limited access to books, newspapers or national political culture. Orators crucially united their dispersed audiences in national struggles for reform, fomenting discussion and coalescing political opinion, while railways, the telegraph and expanding press reportage allowed speakers and their arguments to circulate rapidly. Understanding of political oratory and public meetings has been skewed by over- emphasis upon the hustings and high-profile politicians. This has generated two misconceptions: that political meetings were generally rowdy and that a golden age of political oratory was secured only through Gladstone’s legendary stumping tours. However, this thesis argues that, far from being disorderly, public meetings were carefully regulated and controlled offering disenfranchised males a genuine democratic space for political discussion. -

Ferdinand Freiligrath (Gemälde Von Johann Peter Hasenclever)

1 Ferdinand Freiligrath (Gemälde von Johann Peter Hasenclever) Hermann Ferdinand Freiligrath (* 17. Juni 1810 in Detmold – † 18. März 1876 in Cannstatt bei Stuttgart), bis 1825 Gymnasium in Detmold, 1825-32 Kaufmannslehre in Soest, 1832 Kontoristenstelle in Amsterdam, 1837-1839 Buchhalter in Barmen, seit 1839 freier Schriftsteller in Unkel am Rhein, dann 1841 in Darmstadt, 1843-44 in St. Goar. Auf Empfehlung Alexander von Humboldts erhielt er 1842 vom preußischen König ein Ehrengehalt, wandte sich aber zunehmend republikanischen Idealen zu und verzichtete 1844 auf die königliche Pension. In Brüssel 1845 Bekanntschaft mit Karl Marx und Umzug nach Zürich in die Schweiz, dort Bekanntschaft mit Gottfried Keller und Franz Liszt, 1846 Tätigkeit als Korrespondent in London. 1848 Rückkehr nach Deutschland, Verhaftung wegen seines Appells zum Umsturz, Freispruch und Redakteur in der von Marx hrsg. „Neuen Rheinischen Zeitung“ in Köln bis zu deren Verbot im Jahre 1849. In den folgenden Jahren lebte er – zeitweise steckbrieflich gesucht – in den Niederlanden, in Düsseldorf und in London, wo er 1856 Filialleiter der Schweizer Generalbank wurde. Nach Schließung der Bankfiliale im Jahr 1865 veranstalteten Freunde ein der „Gartenlaube“ eine Sammlung für den Dichter, deren Ergebnis von rund 60.000 Talern ihm die Rückkehr nach Deutschland ermöglichten. Von 1874 bis zu seinem Tode lebte er in Stuttgart-Cannstatt. Freiligrath war vor allem Lyriker und Übersetzer englischer und französischer Lyrik und Versepik. GG 2 [141] Das Nöttentor zu Soest. 1830. (Kurz vor Abbruch desselben gedichtet.) „Uns ist in alten Mären Wunders viel gesungen, Von Helden mit Lob zu ehren, von großen Handelungen Von Freuden und Festlichkeiten, – – – – – – – – – – – – – mögt ihr nun Wunder hören sagen.“ Lied der Nibelungen, Vers 1–4. -

Karl Marx and the Iwma Revisited 299 Jürgen Herres

“Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” <UN> Studies in Global Social History Editor Marcel van der Linden (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Sven Beckert (Harvard University, Cambridge, ma, usa) Dirk Hoerder (University of Arizona, Phoenix, ar, usa) Chitra Joshi (Indraprastha College, Delhi University, India) Amarjit Kaur (University of New England, Armidale, Australia) Barbara Weinstein (New York University, New York, ny, usa) volume 29 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/sgsh <UN> “Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” The First International in a Global Perspective Edited by Fabrice Bensimon Quentin Deluermoz Jeanne Moisand leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Cover illustration: Bannière de la Solidarité de Fayt (cover and back). Sources: Cornet Fidèle and Massart Théophile entries in Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier en Belgique en ligne : maitron-en -ligne.univ-paris1.fr. Copyright : Bibliothèque et Archives de l’IEV – Brussels. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bensimon, Fabrice, editor. | Deluermoz, Quentin, editor. | Moisand, Jeanne, 1978- editor. Title: “Arise ye wretched of the earth” : the First International in a global perspective / edited by Fabrice Bensimon, Quentin Deluermoz, Jeanne Moisand. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2018] | Series: Studies in global social history, issn 1874-6705 ; volume 29 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018002194 (print) | LCCN 2018004158 (ebook) | isbn 9789004335462 (E-book) | isbn 9789004335455 (hardback : alk. -

Walt Whitman

CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN WALT WHITMAN CONSTRUCTING THE GERMAN Walt Whitman BY WALTER GRUNZWEIG UNIVERSITY OF IOWA PRESS 1!11 IOWA CITY University oflowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 1995 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gri.inzweig, Walter. Constructing the German Walt Whitman I by Walter Gri.inzweig. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-87745-481-7 (cloth), ISBN 0-87745-482-5 (paper) 1. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892-Appreciation-Europe, German-speaking. 2. Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892- Criticism and interpretation-History. 3. Criticism Europe, German-speaking-History. I. Title. PS3238.G78 1994 94-30024 8n' .3-dc2o CIP 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 c 5 4 3 2 1 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 p 5 4 3 2 1 To my brother WERNER, another Whitmanite CONTENTS Acknowledgments, ix Abbreviations, xi Introduction, 1 TRANSLATIONS 1. Ferdinand Freiligrath, Adolf Strodtmann, and Ernst Otto Hopp, 11 2. Karl Knortz and Thomas William Rolleston, 20 3· Johannes Schlaf, 32 4· Karl Federn and Wilhelm Scholermann, 43 5· Franz Blei, 50 6. Gustav Landauer, 52 7· Max Hayek, 57 8. Hans Reisiger, 63 9. Translations after World War II, 69 CREATIVE RECEPTION 10. Whitman in German Literature, 77 11. -

Marx and Engels and the Communist Movement the Following Article Is a Chapter from the Idea: Anarchist Communism, Past, Present and Future by Nick Heath

Marx and Engels and the Communist Movement The following article is a chapter from The Idea: Anarchist Communism, Past, Present and Future by Nick Heath. We should point out that whilst we regard Marx's analysis of capitalism and class society as a very important contribution to revolutionary ideas, we are critical of his attitudes and behaviour within both the Communist League and the First International. Marx was to re-iterate his ideas and to put them into practice in all his time in the working class movement. “Without parties no development, without division no progress” he was to write (polemic with the Kölnische Zeitung newspaper, 1842). In a much later letter to Bebel written in 1873, Engels sums up this approach: “For the rest, old Hegel has already said it; a party proves itself a victorious party by the fact that it splits and can stand the split. The movement of the proletariat necessarily passes through stages of development; at every stage one section of the people lags behind and does not join in the further advance; and this alone explains why it is that actually the “solidarity of the proletariat” is everywhere realised in different party groupings which carry on life and death feuds with one another”. The mythology of Marxism implies that the theory of communism was perfected by Marx and Engels without really taking into consideration all that had gone before and that communism, organised more or less into a loose movement, was created by artisans and workers as a result of their practical experiences in the French Revolution and the events of the 1830s, as well as their continuing theoretical labours. -

Karl Marx: Communist As Religious Eschatologist

Karl Marx: Communist as Religious Eschatologist Murray N. Rothbard* Marx as Millennia1 Communist he key to the intricate and massive system of thought created by Karl Marx is at bottom a simple one: Karl Marx was a Tcommunist. A seemingly trite and banal statement set along- side Marxism's myriad of jargon-ridden concepts in philosophy, eco- nomics, and culture, yet Marx's devotion to communism was his crucial focus, far more central than the class struggle, the dialectic, the theory of surplus value, and all the rest. Communism was the great goal, the vision, the desideratum, the ultimate end that would make the sufferings of mankind throughout history worthwhile. History is the history of suffering, of class struggle, of the exploitation of man by man. In the same way as the return of the Messiah, in Christian theology, will put an end to history and establish a new heaven and a new earth, so the establishment of communism would put an end to human history. And just as for post-millennia1 Chris- tians, man, led by God's prophets and saints, will establish a Kingdom of God on Earth (for pre-millennials, Jesus will have many human assistants in setting up such a kingdom), so, for Marx and other schools of communists, mankind, led by a vanguard of secular saints, will establish a secularized Kingdom of Heaven on earth. In messianic religious movements, the millennium is invariably established by a mighty, violent upheaval, an Armageddon, a great apocalyptic war between good and evil. After this titanic conflict, a millennium, a new age, of peace and harmony, of the reign of justice, will be installed upon the earth.