Treatment of History in William Dalrymple's Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hett-Syll-80020-19

The Graduate Center of the City University of New York History Department Hist 80200 Literature of Modern Europe II Thursdays 4:15-6:15 GC 3310A Prof. Benjamin Hett e-mail [email protected] GC office 5404 Office hours Thursdays 2:00-4:00 or by appointment Course Description: This course is intended to provide an introduction to the major themes and historians’ debates on modern European history from the 18th century to the present. We will study a wide range of literature, from what we might call classic historiography to innovative recent work; themes will range from state building and imperialism to war and genocide to culture and sexuality. After completing the course students should have a solid basic grounding in the literature of modern Europe, which will serve as a basis for preparation for oral exams as well as for later teaching and research work. Requirements: In a small seminar class of this nature effective class participation by all students is essential. Students will be expected to take the lead in class discussions: each week one student will have the job of introducing the literature for the week and to bring to class questions for discussion. Over the semester students will write a substantial historiographical paper (approximately 20 pages or 6000 words) on a subject chosen in consultation with me, due on the last day of class, May 13. The paper should deal with a question that is controversial among historians. Students must also submit two short response papers (2-3 pages) on readings for two of the weekly sessions of the course, and I will ask for annotated bibliographies for your historiographical papers on March 28. -

Curriculum Vitae (Updated August 1, 2021)

DAVID A. BELL SIDNEY AND RUTH LAPIDUS PROFESSOR IN THE ERA OF NORTH ATLANTIC REVOLUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Curriculum Vitae (updated August 1, 2021) Department of History Phone: (609) 258-4159 129 Dickinson Hall [email protected] Princeton University www.davidavrombell.com Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 @DavidAvromBell EMPLOYMENT Princeton University, Director, Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies (2020-24). Princeton University, Sidney and Ruth Lapidus Professor in the Era of North Atlantic Revolutions, Department of History (2010- ). Associated appointment in the Department of French and Italian. Johns Hopkins University, Dean of Faculty, School of Arts & Sciences (2007-10). Responsibilities included: Oversight of faculty hiring, promotion, and other employment matters; initiatives related to faculty development, and to teaching and research in the humanities and social sciences; chairing a university-wide working group for the Johns Hopkins 2008 Strategic Plan. Johns Hopkins University, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities (2005-10). Principal appointment in Department of History, with joint appointment in German and Romance Languages and Literatures. Johns Hopkins University. Professor of History (2000-5). Johns Hopkins University. Associate Professor of History (1996-2000). Yale University. Assistant Professor of History (1991-96). Yale University. Lecturer in History (1990-91). The New Republic (Washington, DC). Magazine reporter (1984-85). VISITING POSITIONS École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Visiting Professor (June, 2018) Tokyo University, Visiting Fellow (June, 2017). École Normale Supérieure (Paris), Visiting Professor (March, 2005). David A. Bell, page 1 EDUCATION Princeton University. Ph.D. in History, 1991. Thesis advisor: Prof. Robert Darnton. Thesis title: "Lawyers and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Paris (1700-1790)." Princeton University. -

The Futures of Global History

Richard Drayton and David Motadel Discussion: the futures of global history Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Drayton, Richard and Motadel, David (2018) Discussion: the futures of global history. Journal of Global History, 13 (1). pp. 1-21. ISSN 1740-0228 DOI: 10.1017/S1740022817000262 © 2018 Cambridge University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/86797/ Available in LSE Research Online: February 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. The Futures of Global History Richard Drayton and David Motadel ‘If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are citizen of nowhere’, declared Theresa May in autumn 2016 to the Tory party conference, questioning the patriotism of those who still dared to question Brexit. Within a month, ‘Make America Great Again’ triumphed in the polls in the United States. -

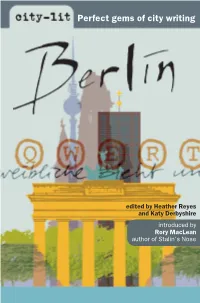

Introducing BERLIN by Rory Maclean Why Are We Drawn to Certain Cities? Perhaps Because of a Story Read in Childhood

city-lit BERLIN Oxygen Books Published by Oxygen Books 2009 This selection and commentary copyright © Heather Reyes 2009 Copyright Acknowledgements at the end of this volume constitute an extension of this copyright page. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978–0–9559700–4–7 Typeset in Sabon by Bookcraft Limited, Stroud, Gloucestershire Printed and bound in India by Imago Praise for city-lit series ‘Brilliant … the best way to get under the skin of a city. The perfect read for travellers and book lovers of all ages’ Kate Mosse, best-selling author of Labyrinth ‘An inviting new series of travel guides which collects some of the best writing on European cities to give a real flavour of the place … Such ’an idéeformidable, it seems amazing it hasn’t been done before Editor’s Pick, The Bookseller ‘This impressive little series’ Sunday Telegraph ‘An attractive-looking list of destination-based literature anthologies … a great range of writers’ The Independent ‘ … something for everyone – an ideal gift’ Travel Bookseller ‘A very clever idea: take the best and most beloved books about a city, sift through -

Greater Britain: a Useful Category of Historical Analysis?

!"#$%#"&'"(%$()*&+&,-#./0&1$%#23"4&3.&5(-%3"(6$0&+)$04-(-7 +/%83"9-:*&;$<(=&+">(%$2# ?3/"6#*&@8#&+>#"(6$)&5(-%3"(6$0&A#<(#BC&D30E&FGHC&I3E&JC&9+K"EC&FLLL:C&KKE&HJMNHHO P/Q0(-8#=&Q4*&+>#"(6$)&5(-%3"(6$0&+--36($%(3) ?%$Q0#&,AR*&http://www.jstor.org/stable/2650373 +66#--#=*&SGTGUTJGGV&FV*SU Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aha. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org AHR Forum Greater Britain: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis? DAVID ARMITAGE THE FIRST "BRITISH" EMPIRE imposed England's rule over a diverse collection of territories, some geographically contiguous, others joined to the metropolis by navigable seas. -

The Clan Gillean

Ga-t, $. Mac % r /.'CTJ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/clangilleanwithpOOsinc THE CLAN GILLEAN. From a Photograph by Maull & Fox, a Piccadilly, London. Colonel Sir PITZROY DONALD MACLEAN, Bart, CB. Chief of the Clan. v- THE CLAN GILLEAN BY THE REV. A. MACLEAN SINCLAIR (Ehartottftcton HASZARD AND MOORE 1899 PREFACE. I have to thank Colonel Sir Fitzroy Donald Maclean, Baronet, C. B., Chief of the Clan Gillean, for copies of a large number of useful documents ; Mr. H. A. C. Maclean, London, for copies of valuable papers in the Coll Charter Chest ; and Mr. C. R. Morison, Aintuim, Mr. C. A. McVean, Kilfinichen, Mr. John Johnson, Coll, Mr. James Maclean, Greenock, and others, for collecting- and sending me genea- logical facts. I have also to thank a number of ladies and gentlemen for information about the families to which they themselves belong. I am under special obligations to Professor Magnus Maclean, Glasgow, and Mr. Peter Mac- lean, Secretary of the Maclean Association, for sending me such extracts as I needed from works to which I had no access in this country. It is only fair to state that of all the help I received the most valuable was from them. I am greatly indebted to Mr. John Maclean, Convener of the Finance Committee of the Maclean Association, for labouring faithfully to obtain information for me, and especially for his efforts to get the subscriptions needed to have the book pub- lished. I feel very much obliged to Mr. -

The Travel Writing and Narrative History of William Dalrymple

Travelling into History: The Travel Writing and Narrative History of William Dalrymple By Rebecca Dor gel o BA (Hons) Tas MA Tas Submitted in fulfilment of the r equi r ements for the Degr ee of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmani a July 2011 ii Declaration of Originality The thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my k now l ed ge and bel i ef no mat er i al pr ev i ousl y publ i shed or w r i tten by another per son except w her e d ue ack now l ed gement i s made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Si gned , Rebecca Dorgelo. 18 July 2011 Authority of Access The thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance w ith the Copyright Act 1968. Si g n ed , Rebecca Dorgelo. 18 July 2011 iii iv Abstract: “Travelling into History: The Travel Writing and N arrative History of William Dalrymple” Doctor of Philosophy. William Dalrymple is a popular, bestselling author, initially known for his travel writing and subsequently for his popular narrative histories. He is also a prolific journalist and reviewer. His major publications include: In Xanadu: A Quest (1990), City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi (1993), Fr om t he H ol y M ount ai n: A Jour ney i n t he Shadow of Byzant i um (1997), T he Age of Kali: Indian Travels & Encounters (1998), White M ughals: Lov e & Bet r ay al i n Ei ght een t h-Century India (2002), The Last M ughal : The Fal l of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857 (2006), and N i n e L i v es: I n Sear ch of t he Sacr ed i n M odern India (2009). -

Myanmar (Burma): a Reading Guide Andrew Selth

Griffith Asia Institute Research Paper Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide Andrew Selth i About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally recognised research centre in the Griffith Business School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding commitment and future aspirations for the study of and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific— cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s Asia-Pacific future. We do this by: i) conducting and supporting excellent and relevant research on the politics, security, economies and development of the Asia-Pacific region; ii) facilitating high level dialogues and partnerships for policy impact in the region; iii) leading and informing public debate on Australia’s place in the Asia Pacific; and iv) shaping the next generation of Asia-Pacific leaders through positive learning experiences in the region. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Research Papers’ publish the institute’s policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asia-institute ‘Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide’ February 2021 ii About the Author Andrew Selth Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University. He has been studying international security issues and Asian affairs for 45 years, as a diplomat, strategic intelligence analyst and research scholar. Between 1974 and 1986 he was assigned to the Australian missions in Rangoon, Seoul and Wellington, and later held senior positions in both the Defence Intelligence Organisation and Office of National Assessments. -

Online Course Title: 20Th Century Berlin: People, Places, Words Instructor

Online course title: 20th Century Berlin: People, Places, Words Instructor: Lauren Van Vuuren, Ph.D. Email address: [email protected] Course days: Monday and Thursday Language of instruction: English Contact hours: The coursework corresponds to an on-site course amounting to 48 contact hours. ECTS credits: 4 Prerequisites: Students should be able to speak and read English at the upper intermediate level (B2), preferably even higher. Interest in Berlin, and its extraordinary recent past. General requirements: Please make sure to be online approximately from 4 pm CEST to 8:30 pm CEST on the respective course days! Therefore, please check the possible time difference between Germany and your country of residence. We also recommend that you make sure to have a quiet and appropriate working space. To ensure a comfortable learning environment for all, please adhere to general netiquette rules. Technical requirements: - stable internet connection - fully functional device, such as computer, laptop or tablet (use of smart phones not recommended), headset recommended - recommended operating systems: Windows 7 or higher or Mac OS X 10,13 or higher, avoid using a VPN __________________________________________________________________________ Course description This course is about Berlin, and the story of its tumultuous and epoch defining twentieth century. We examine this history through various lenses: the biographies of individuals, the words of writers who bore witness to the vertiginous social, political and physical changes the city underwent, and buildings and monuments whose physical construction, destruction and reconstruction reflected the ideological turmoil and conflict of twentieth century Berlin. Famous Berliners we will meet include the murdered Communist leader Rosa Luxemburg, the artist Käthe Kollwitz, the actress Marlene Dietrich, the Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, the adopted Berliner David Bowie and the famous East German dissident musician Wolf Biermann. -

We All Global Historians Now? an Interview with David Armitage

Itinerario http://journals.cambridge.org/ITI Additional services for Itinerario: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Are We All Global Historians Now? An Interview with David Armitage Martine van Ittersum and Jaap Jacobs Itinerario / Volume 36 / Issue 02 / August 2012, pp 7 28 DOI: 10.1017/S0165115312000551, Published online: Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0165115312000551 How to cite this article: Martine van Ittersum and Jaap Jacobs (2012). Are We All Global Historians Now? An Interview with David Armitage. Itinerario, 36, pp 728 doi:10.1017/S0165115312000551 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ITI, IP address: 128.103.149.52 on 02 Nov 2012 7 Are We All Global Historians Now? An Interview with David Armitage BY MARTINE VAN ITTERSUM AND JAAP JACOBS The interview took place on a splendid summer day in Cambridge, Massa- chusetts. The location was slightly exotic: the interviewers had lunch with David Armitage at Upstairs at the Square, an eatery which sports pink and mint green walls, zebra decorations, and even a stuffed crocodile. What more could one want? Armitage was recently elected Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. At the time of the interview, he was just about to take over as Chair of the History Department at Harvard University. His long-awaited Foundations of Modern International Thought (2013) was being copy-edited for publication.1 Granted a sneak preview, the interviewers can recommend it to every Itinerario reader. In short, it was high time for Itinerario to sit down with one of the movers and shakers of the burgeoning field of global and international history for a long and wide-ranging conversation. -

Simon Payaslian Authors New History of Armenia

January 2008 Simon Payaslian authors new history of Armenia In December Palgrave Macmillan published Professor Simon Payaslian’s The History of Armenia. In his Preface, the author presents the volume as a survey of the history of Armenia from antiquity to the pres- ent, with a focus on four major themes: East-West geopolitical competi- tions, Armenian culture (e.g., language and religion), political leader- ship (e.g., nakharars or the nobility, intellectuals and party leaders), and the struggle for national survival. It places Armenian history within the broader context of secularization, modernization, and globalization. We are pleased to reprint a section from a chapter on “Independ- ence and Democracy: The Second Republic”: rmenians worldwide greeted the independence regained by the Republic of Armenia with great fanfare and jubilation. ASeven decades of Soviet hegemonic rule had come to an end, and Armenian expectations and imaginations soared high. National sovereignty strengthened national pride, and Armenians once more considered themselves as belonging to the community of nation-states. And the Republic of Armenia had much to be proud of, for it had built a modern country, even if under the shadow of the Stalinist legacy. Clearly the newly independent republic in 1991 appeared infinitesimally different from the soci- ety that had fallen to the Bolsheviks in 1921. Soon after inde- pendence, however, it became apparent that domestic sys- temic deficiencies would not permit the immediate introduc- tion of political and economic policies predicated on princi- ples of democratization and liberalization. The obsolete institutions, bureaucratic customs, and the political culture as developed under the Communist Party hindered the transition from the centrally planned system to a more decentralized, democratic polity. -

Reordering the World: Essays on Liberalism and Empire

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Introduction • Reordering the World [C]entral to the lives of all empires have been the ways in which they have been constituted through language and their own self- representations: the discourses that have arisen to describe, defend, and criticize them, and the historical narratives that have been invoked to make sense of them.1 —Jennifer Pitts rom the earliest articulations of political thinking in the European tradi- Ftion to its most recent iterations, the nature, justification, and criticism of foreign conquest and rule has been a staple theme of debate. Empires, after all, have been among the most common and the most durable political formations in world history. However, it was only during the long nineteenth century that the European empire- states developed sufficient technological superiority over the peoples of Africa, the Americas, and Asia to make occupation and governance on a planetary scale seem both feasible and desirable, even if the reality usually fell far short of the fantasy. As Jürgen Osterhammel reminds us, the nineteenth century was “much more an age of empire than . an age of nations and nation-s tates.”2 The largest of those empires was governed from London. Even the most abstract works of political theory, Quentin Skinner argues, “are never above the battle; they are always part of the battle itself.”3 The ideo- 1 Pitts, “Political Theory of Empire and Imperialism,” Annual Review of Political Science, 13 (2010), 226.