1 Knight Or Wight in Keats's 'La Belle Dame'?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAUCER and CHIVALRY by Francine Renee Hall (Knight Templar Magazine, Page 28, Dec

1. He was a verray, parfit, gentil knyght"... CHAUCER AND CHIVALRY by Francine Renee Hall (Knight Templar Magazine, page 28, Dec. 1980) (Reprinted Knight Templar Magazine, pages 16-17, August 2001) In his medieval classic, "The Canterbury Tales," Geoffrey Chaucer is quite deliberate when he introduces his cast of characters with the Knight. Although chivalry was a stylized code of behavior that signaled the decay of the medieval feudal system, Chaucer is upholding what is essentially the perfect expression of earthly behavior with divine aspiration -- knighthood. During the Age of Chivalry, the ideal knight owed fealty to his king. The king considered himself God's intermediary, so a knight's military obedience became not only a spiritual defense of Christendom in general but a personal homage to God. In the Middle Ages, God was often referred to as the "Lord" and "Heaven-King"; therefore, when Chaucer tells us that the Knight "had proved his worth in his *lord's* wars," we can easily interpret this as meaning God Himself. Chaucer's Knight, then, becomes the standard by which the other pilgrims are gauged. And the Pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury becomes more than an opportunity to journey to a different place and tell stories -- the presence of the Knight transforms it to a spiritual quest. What is the history of this saintly English Knight who leads the "company of nine and twenty" on their pilgrimage to Canterbury and who sets the spiritual tone of the journey? He "loved chivalry, truth and honor, liberality and courtesy." He also "proved his worth" in the holy wars and yet he is humble: "Although he was valiant, he was prudent, never in all his life had he been rude to anyone at all. -

Articles of Chivalry

TThhee AArrttiicclleess ooff CChhiivvaallrryy We as Chivalric Knights of the Holy Order of the Fellow Soldiers of Jacques DeMolay, as we affix our signatures to this set of articles, do hereby agree to uphold them as a covenant upon which we wish to base our lives as Sir Knights. We further recognize that through the incorporation of these articles into our lives, we can better represent ourselves and the Order of DeMolay. We further assert our willingness to be removed from the roles of Knighthood should it ever be found that our conduct has been contrary to the principles herein set. Article 1 - A Sir Knight is Honorable 1. A Sir Knight must accept responsibility for the one thing that is within his control: himself. 2. A Sir Knight must always keep his word, realizing that a man who's word is as good as his bond is held in high esteem by all. 3. A Sir Knight must never speak harshly or critically of a Brother, unless it be in private and tempered with the love one Brother has for another, always speaking to him for the purpose of aiding him to be a better man. 4. A Sir Knight must always rely on his instincts and those lessons taught to him throughout the course of his DeMolay career when deciding right from wrong. Article 2 - A Sir Knight Shows Excellence 1. A Sir Knight must commit to excellence, and seek the highest level of excellence in all aspects of his life. 2. A Sir Knight must always excel in his education, putting forth his best effort in all his school works. -

Feudal Contract – Medieval Europe

FEUDAL CONTRACT – MEDIEVAL EUROPE Imagine you are living in Medieval Europe (500 – 1500). Despite the fact that a feudal contract is an unwritten contract, write out a feudal contract. You and a partner will take on the roles of lord and vassal: - You Need to Write Out the Contract: - The lord can have a certain title (i.e. duke/duchess, baron/baroness, or count/countess), and specify what social standing the vassal has (i.e. lower-level knight, peasant, etc.). - In your contract, specify how much acreage in land (fief) will be given to the vassal. - Specify how much military service the vassal will serve, and what kind of fighting they will do (i.e. cavalry, foot soldier…) - How much money will a vassal provide his lord if he is kidnapped, and if there is a ransom? How much will a vassal provide for one of the lord’s children’s weddings? (Specify money in terms of weight and precious metal such as “30 lbs. gold”). - Specify other duties from the readings (Feudalism HW and class handout) that will be done by a lord and vassal (i.e. the lord will give safety and will defend his vassal in court). - List any other duties a lord/vassal will do of your choosing. (i.e. farm a certain crop, make a certain craft) - Define feudalism, fief, knight, vassal, and serfs. - Sign and date your contract at the bottom to make it official, and make sure the date is between the year 500 and 1500. Example: Lord/Vassal Feudal Contract: I am a peasant (name of vassal) and will serve and be the vassal of (name of Lord/Duke). -

Knight's Code of Chivalry

Knight’s Code of Chivalry http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/knights-code-of-chivalry.htm The medieval knightly system had a religious, moral, and social code dating back to the Dark Ages. The Knights Code of Chivalry and the legends of King Arthur and Camelot The ideals described in the Code of Chivalry were emphasised by the oaths and vows that were sworn in the Knighthood ceremonies of the Middle Ages and Medieval era. These sacred oaths of combat were combined with the ideals of chivalry and with strict rules of etiquette and conduct. The ideals of a Knights Code of Chivalry was publicised in the poems, ballads, writings and literary works of Knights’ authors. The wandering minstrels of the Middle Ages sang these ballads and were expected to memorize the words of long poems describing the valour and the code of chivalry followed by the Medieval knights. The Dark Age myths of Arthurian Legends featuring King Arthur, Camelot and the Knights of the Round Table further strengthen the idea of a Knights’ Code of Chivalry. The Arthurian legend revolves around the Code of Chivalry which was adhered to by the Knights of the Round Table - Honour, Honesty, Valour and Loyalty. A knight was expected to have not only the strength and skills to face combat in the violent Middle Ages but was also expected to temper this aggressive side of a knight with a chivalrous side to his nature. There was not an authentic Knights’ Code of Chivalry as such - it was a moral system which went beyond rules of combat and introduced the concept of Chivalrous conduct - qualities idealized by knighthood, such as bravery, courtesy, honor, and gallantry toward women. -

The Princess Knight

THE PRINCESS KNIGHT By Martin Follose Copyright © MCMXCVI by Martin Follose All Rights Reserved Heuer Publishing LLC, Cedar Rapids, Iowa Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this work is subject to a royalty. Royalty must be paid every time a play is performed whether or not it is presented for profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is performed any time it is acted before an audience. All rights to this work of any kind including but not limited to professional and amateur stage performing rights are controlled exclusively by Heuer Publishing LLC. Inquiries concerning rights should be addressed to Heuer Publishing LLC. This work is fully protected by copyright. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. Copying (by any means) or performing a copyrighted work without permission constitutes an infringement of copyright. All organizations receiving permission to produce this work agree to give the author(s) credit in any and all advertisement and publicity relating to the production. The author(s) billing must appear below the title and be at least 50% as large as the title of the Work. All programs, advertisements, and other printed material distributed or published in connection with production of the work must include the following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Heuer Publishing LLC of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.” There shall be no deletions, alterations, or changes of any kind made to the work, including the changing of character gender, the cutting of dialogue, or the alteration of objectionable language unless directly authorized by the publisher or otherwise allowed in the work’s “Production Notes.” The title of the play shall not be altered. -

Creation of Order of Chivalry Page 0 of 72

º Creation of Order of Chivalry Page 0 of 72 º PREFACE Knights come in many historical forms besides the traditional Knight in shining armor such as the legend of King Arthur invokes. There are the Samurai, the Mongol, the Moors, the Normans, the Templars, the Hospitaliers, the Saracens, the Teutonic, the Lakota, the Centurions just to name a very few. Likewise today the Modern Knight comes from a great variety of Cultures, Professions and Faiths. A knight was a "gentleman soldier or member of the warrior class of the Middle Ages in Europe. In other Indo-European languages, cognates of cavalier or rider French chevalier and German Ritter) suggesting a connection to the knight's mode of transport. Since antiquity a position of honor and prestige has been held by mounted warriors such as the Greek hippeus and the Roman eques, and knighthood in the Middle Ages was inextricably linked with horsemanship. Some orders of knighthood, such as the Knights Templar, have themselves become the stuff of legend; others have disappeared into obscurity. Today, a number of orders of knighthood continue to exist in several countries, such as the English Order of the Garter, the Swedish Royal Order of the Seraphim, and the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav. Each of these orders has its own criteria for eligibility, but knighthood is generally granted by a head of state to selected persons to recognize some meritorious achievement. In the Legion of Honor, democracy became a part of the new chivalry. No longer was this limited to men of noble birth, as in the past, who received favors from their king. -

![World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1845/world-history-part-1-teachers-guide-and-student-guide-2081845.webp)

World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 784 EC 308 847 AUTHOR Schaap, Eileen, Ed.; Fresen, Sue, Ed. TITLE World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [and Student Guide]. Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS). INSTITUTION Leon County Schools, Tallahassee, FL. Exceptibnal Student Education. SPONS AGENCY Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 841p.; Course No. 2109310. Part of the Curriculum Improvement Project funded under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. AVAILABLE FROM Florida State Dept. of Education, Div. of Public Schools and Community Education, Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Turlington Bldg., Room 628, 325 West Gaines St., Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400. Tel: 850-488-1879; Fax: 850-487-2679; e-mail: cicbisca.mail.doe.state.fl.us; Web site: http://www.leon.k12.fl.us/public/pass. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF05/PC34 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Accommodations (Disabilities); *Academic Standards; Curriculum; *Disabilities; Educational Strategies; Enrichment Activities; European History; Greek Civilization; Inclusive Schools; Instructional Materials; Latin American History; Non Western Civilization; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Methods; Textbooks; Units of Study; World Affairs; *World History IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT This teacher's guide and student guide unit contains supplemental readings, activities, -

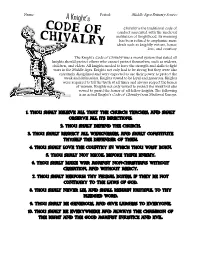

Middle Ages Primary Source Chivalry Is the Traditional Code

Name: ______________________________ Period: _____ Middle Ages Primary Source Chivalry is the traditional code of conduct associated with the medieval institution of knighthood. Its meaning has been refined to emphasize more ideals such as knightly virtues, honor, love, and courtesy. The Knight's Code of Chivalry was a moral system that stated all knights should protect others who cannot protect themselves, such as widows, children, and elders. All knights needed to have the strength and skills to fight wars in the Middle Ages. Knights not only had to be strong but they were also extremely disciplined and were expected to use their power to protect the weak and defenseless. Knights vowed to be loyal and generous. Knights were required to tell the truth at all times and always respect the honor of women. Knights not only vowed to protect the weak but also vowed to guard the honor of all fellow knights. The following is an actual Knight’s Code of Chivalry from Medieval Europe. 1. Thou shalt believe all that the Church teaches, and shalt observe all its directions. 2. Thou shalt defend the Church. 3. Thou shalt respect all weaknesses, and shalt constitute thyself the defender of them. 4. Thou shalt love the country in which thou wast born. 5. Thou shalt not recoil before thine enemy. 6. Thou shalt make war against non-Christians without cessation, and without mercy. 7. Thou shalt perform thy feudal duties, if they be not contrary to the laws of God. 8. Thou shalt never lie, and shall remain faithful to thy pledged word. -

Coase, Knight, and the Nexus-Of-Contracts Theory of the Firm: a Reflection on Reification, Reality, and the Corporation As Entrepreneur Surrogate

Coase, Knight, and the Nexus-of-Contracts Theory of the Firm: A Reflection on Reification, Reality, and the Corporation as Entrepreneur Surrogate Charles R. T. O’Kelley* I. INTRODUCTION Scholars routinely credit R. H. Coase and his first seminal work— The Nature of the Firm1—as the progenitor of the nexus-of-contracts the- ory of the corporation.2 This account, which has dominated legal scholar- ship for four decades, describes a corporation as a nexus of contracts be- tween the various claimants to the earnings of the business— shareholders, directors, officers, employees, customers, suppliers, and other factors of production.3 In this Article, I will argue for a different * Professor and Director, Adolf A. Berle, Jr. Center on Corporations, Law & Society, Seattle Uni- versity School of Law; Martin E. Kilpatrick Chair Emeritus, University of Georgia School of Law. 1. R. H. Coase, The Nature of the Firm, 4 ECONOMICA 386 (1937). 2. See, e.g., Stephen Bainbridge, The Board of Directors as Nexus of Contracts, 88 IOWA L. REV. 1, 9 (2002) (“The dominant model of the corporation in legal scholarship is the so-called nexus of contracts theory. This model’s origins fairly can be traced to Nobel Prize laureate Ronald Coase’s justly famous article, The Nature of the Firm.”); see also Angus Corbett & Peta Spender, Corporate Constitutionalism, 31 SYDNEY L. REV. 147 (2009) (“Since the rediscovery of the Coase Theorem by Jensen and Meckling in the late 1970s, corporate law theory has been dominated by economic analy- sis which posits that the corporation is a nexus of contracts.”); David Millon, Theories of the Corpo- ration, 1990 DUKE L.J. -

70 Lords, Knights and Gentry the 13Th Century Sees the Start of Changes

70 Lords, Knights and Gentry The 13th Century sees the start of changes that will come to full fruit in the 14th Century - the development of the role of the knight in the shires, the appearance of the 'Gentleman', Bastard Feudalism. Fountains Abbey Cistercians at work in a detail from the Life of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, illustrated by Jörg Breu the Elder (1500) St. Bernard de Clairveau ? Arms of Fitz Elys Land use A Glossary of Terms FEUDAL/Feudalism/Feudalize governing system of nobility in medieval Europe, relating to a fief FEUD abbreviation for Feudal FEUDAL CHARGES/Aids vassal payment to lord for his going on Crusade, son's knighting FEUDALITY regime or feudal system FEUDAL LEVY army obligation a lord needs to field a number of knights and men-at-arms for 40 days service in the kings army in exchange for land. A liegeman would go to the royal castle with necessary warhorse, armament and attendants specified by contract. FEUDAL PYRAMID king over sub-tenants FEUDAL REGIME holding to a feudal system FEUDAL SERVICE vassal holding land from a lord in exchange for military service FEUDAL SYSTEM from lord to vassal, homage and fealty, and enfeoffment FEUDAL DEMESNE ANCIENT DEMESNE land held by the king at the time of the Domesday Book. CUSTOMAL written collection of a manor’s customs DEMESNE manor land held by free or villein tenants but directly cultivated for the lord by an agent MESSUAGE portion of land occupied as a site for a swelling or house and all appurtenances FEUDAL LORD AVOWRY lord of the manor LIEGE feudal lord over a vassal -

Order of Chivalry HERALD Let All Members of the Order of Chivalry Come Forward, and Attend Their Majesties

Order of Chivalry HERALD Let all members of the Order of Chivalry come forward, and attend Their Majesties. The Knights come forward and kneel, including those who will escort the Candidate. A central aisle is kept open. Since ancient times, it has been recognized that there are certain warriors who are much deserving of high honor, not only by their skill at arms, but by their noble behavior, which came to define the meaning of chivalry. For a Kingdom is supported by these three things: service, art, and valor. And without any one of these, the Kingdom topples. Therefore was created the Order of Knighthood of our Society, to recognize those who, possessing all the other skills, virtues, and attributes appropriate to members of the Peerage, shall also have distinguished themselves by their prowess at arms and chivalrous demeanor. This Order is formed like unto the Knightly Orders of old, with the accolade passing in unbroken descent from knight to knight. And the symbols of this Order are a white belt and an unadorned chain. For the white belt betokens the honor with which the knight girds (himself/herself), and the chain, the duty (s/he) accepts. This Order ranks in precedence with the Order of the Laurel, the Order of the Pelican, and the Order of Defense, and carries with it a Patent of Arms. KING Sir N., please bring forward N. The escort leads his brother knights of escort to the rear of the assembly, where the Candidate is waiting with his accoutrements. The knights escort the candidate before the thrones, arranged with the candidate in the center, flanked by the sponsor and the shield/banner bearer, followed by the bearers of the candidate’s sword and spurs. -

The Story of a Husband and Wife, Knight and Dame of the Order, Volunteers in the Holy Land

The story of a husband and wife, Knight and Dame of the Order, volunteers in the Holy Land Carola and Henrique Abreu, Dame and Knight in the Order of the Holy Sepulchre, left their home in Brazil to place themselves at the service of the Church in the Holy Land. "When we joined the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem we took an oath of devotion and allegiance to the Catholic Church and the Holy Land. We first arrived in the Holy Land as pilgrims, an important first step for every Knight. We realized then the extent of our responsibility towards Christians present here. We discovered their needs, i.e. school education, to have a home, a family, a job, and a life of freedom. It was at this time that we took the decision to engage in this mission to help, support, and serve, the communities present in the Holy Land". "After the visit of the Holy Father to Brazil last year and his frequent gestures of humility, simplicity and attention to the poor, we received a strong spiritual call to come to the Holy Land as a family, to serve the Church and the local Christians. We had a comfortable situation in Brazil. As a family we reflected on the possibility of dedicating a few years as volunteers in a more modest setting. We sold the car and the house and we left with only four suitcases for Jerusalem". Carola and Henrique settled in Jerusalem in February 2014 after having travelled in the Holy Land for the previous 5 years, and having discovered what they describe as “the great and heroic work of our priests, who face many difficulties and challenges”.