A Textual Analysis of Browning's Freaks (1932)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bodies Without Borders: Body Horror As Political Resistance in Classical

Bodies without Borders: Body Horror as Political Resistance in Classical Hollywood Cinema By Kevin Chabot A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2013 Kevin Chabot Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94622-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94622-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Missions and Film Jamie S

Missions and Film Jamie S. Scott e are all familiar with the phenomenon of the “Jesus” city children like the film’s abused New York newsboy, Little Wfilm, but various kinds of movies—some adapted from Joe. In Susan Rocks the Boat (1916; dir. Paul Powell) a society girl literature or life, some original in conception—have portrayed a discovers meaning in life after founding the Joan of Arc Mission, variety of Christian missions and missionaries. If “Jesus” films while a disgraced seminarian finds redemption serving in an give us different readings of the kerygmatic paradox of divine urban mission in The Waifs (1916; dir. Scott Sidney). New York’s incarnation, pictures about missions and missionaries explore the East Side mission anchors tales of betrayal and fidelity inTo Him entirely human question: Who is or is not the model Christian? That Hath (1918; dir. Oscar Apfel), and bankrolling a mission Silent movies featured various forms of evangelism, usually rekindles a wealthy couple’s weary marriage in Playthings of Pas- Protestant. The trope of evangelism continued in big-screen and sion (1919; dir. Wallace Worsley). Luckless lovers from different later made-for-television “talkies,” social strata find a fresh start together including musicals. Biographical at the End of the Trail mission in pictures and documentaries have Virtuous Sinners (1919; dir. Emmett depicted evangelists in feature films J. Flynn), and a Salvation Army mis- and television productions, and sion worker in New York’s Bowery recent years have seen the burgeon- district reconciles with the son of the ing of Christian cinema as a distinct wealthy businessman who stole her genre. -

The Horror Film Series

Ihe Museum of Modern Art No. 11 jest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Saturday, February 6, I965 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Museum of Modern Art Film Library will present THE HORROR FILM, a series of 20 films, from February 7 through April, 18. Selected by Arthur L. Mayer, the series is planned as a representative sampling, not a comprehensive survey, of the horror genre. The pictures range from the early German fantasies and legends, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (I9I9), NOSFERATU (1922), to the recent Roger Corman-Vincent Price British series of adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe, represented here by THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (I96IO. Milestones of American horror films, the Universal series in the 1950s, include THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925), FRANKENSTEIN (1951), his BRIDE (l$55), his SON (1929), and THE MUMMY (1953). The resurgence of the horror film in the 1940s, as seen in a series produced by Val Lewton at RR0, is represented by THE CAT PEOPLE (19^), THE CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE (19^4), I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (19*£), and THE BODY SNAT0HER (19^5). Richard Griffith, Director of the Film Library, and Mr. Mayer, in their book, The Movies, state that "In true horror films, the archcriminal becomes the archfiend the first and greatest of whom was undoubtedly Lon Chaney. ...The year Lon Chaney died [1951], his director, Tod Browning,filmed DRACULA and therewith launched the full vogue of horror films. What made DRACULA a turning-point was that it did not attempt to explain away its tale of vampirism and supernatural horrors. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Moma More Cruel and Unusual Comedy Social Commentary in The

MoMA Presents: More Cruel and Unusual Comedy: Social Commentary in the American Slapstick Film Part 2 October 6-14, 2010 Silent-era slapstick highlighted social, cultural, and aesthetic themes that continue to be central concerns around the world today; issues of race, gender, propriety, and economics have traditionally been among the most vital sources for rude comedy. Drawing on the Museum’s holdings of silent comedy, acquired largely in the 1970s and 1980s by former curator Eileen Bowser, Cruel and Unusual Comedy presents an otherwise little-seen body of work to contemporary audiences from an engaging perspective. The series, which first appeared in May 2009, continues with films that take aim at issues of sexual identity, substance abuse, health care, homelessness and economic disparity, and Surrealism. On October 8 at 8PM, Ms Bowser will address the connection between silent comedy and the international film archive movement, when she introduces a program of shorts that take physical comedy to extremes of dream-like invention and destruction. Audiences today will find the vulgar zest and anarchic spirit of silent slapstick has much in common with contemporary entertainment such as Cartoon Network's Adult Swim, MTV's Jackass and the current Jackass 3-D feature. A majority of the films in the series are archival rarities, often the only known surviving version, and feature lesser- remembered performers on the order of Al St. John, Lloyd Hamilton, Fay Tincher, Hank Mann, Lupino Lane, and even one, Diana Serra Cary (a.k.a. Baby Peggy), who, at 91, is the oldest living silent film star still active. -

Freaks Production Notes and Credits Cast

Freaks American horror film, released in 1932, a grotesque revenge melodrama in which director Tod Browning explored the world of carnival sideshows and the “freaks” that starred in them. The story centres on the machinations of a femme fatale, the “normal” trapeze artist Cleopatra (played by Olga Baclanova), who seduces and marries one of the “freaks,” the little person Hans (Harry Earles), after learning that he has inherited a large fortune. Once the other sideshow performers learn of her self-serving plot to poison Hans with the help of her lover, circus strongman Hercules (Henry Victor), they exact a horrific revenge on the two, stabbing the strongman and viciously mutilating Cleopatra. At the end of the film as originally cut, Hercules is seen singing falsetto after being castrated, while Cleopatra—now tarred and feathered, minus her tongue and legs, with her hands deformed—is shown squawking and performing in her new role as a “chicken woman.” In subsequent cuts the castration scene was removed. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer also filmed a revised ending in which Hans reunites with his original lover, the little person Frieda (Daisy Earles). Browning, who once traveled with a circus, cast real carnival performers—including people of short stature, conjoined twins, bearded ladies, microcephalics, and limbless sideshow performers. He contrasted their honesty and integrity with the degeneracy displayed by the true monsters in the film, the so-called “normal” people. Called “ghastly” and “repellent” by critics, Freaks was banned in several places—including in the United Kingdom for some 30 years. Though it later attained cult status, the controversial film effectively ended Browning’s directorial career. -

Exploitative to Favorable, Freak to Ordinary: The

EXPLOITATIVE TO FAVORABLE, FREAK TO ORDINARY: THE EVOLUTION OF DISABILITY REPRESENTATION IN FILM By Julia E. Thompson A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Studies Division of Ohio Dominican University Columbus, Ohio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH DECEMBER 2015 iii CONTENTS CERTIFICATION PAGE ………………………………………………………………… ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ………………………………………………………………. iv CHAPTER 1: A HISTORY OF DISABILITY …………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER 2: FREAK SHOWS AND PHYSICAL DISABILITIES …………………….. 6 CHAPTER 3: DIFFERENT STIGMA: SENSORY DISABILITY ON FILM …………… 15 CHAPTER 4: REGRESSIVE VERSUS PROGRESSIVE DEPICTION ………………… 27 WORKS CITED ………………………………………………………………………….. 35 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the faculty of the Master of Arts graduate program at Ohio Dominican University. You have opened my mind to the infinite rewards of studying literature, poetry, philosophy, and film. Specifically, I want to thank Dr. Ann Hall for her guidance and encouragement from the very beginning of my journey in the graduate program all the way through to the completion of this thesis. Your support and faith in my abilities allowed me to reach my goal. Also, I would like to thank Dr. Martin Brick for his support and review. My success in the graduate program would not have been possible without the love, support, and unwavering encouragement of my husband, Eric. Thank you for assuming even more of the responsibilities for our children and our home while I worked through the program and this thesis. Thank you also to my children, Celeste and Sawyer, who have been so very patient with me. I hope that my excitement for education influences your own outlook. -

82635751.Pdf (469.1Kb)

MASTERGRADSOPPGAVE I TEATERVITENSKAP Den abnormale kroppen Kropp og funksjonshemming: freaks i teater og film Institutt for lingvistiske, litterære og estetiske studier Universitetet i Bergen VÅR 2011 Karoline Bergsagel Skuseth 1 Abstract In this thesis I aim to explore the ethic-esthetical issues that concern the staging of abnormal bodies. The disabled body is still seen as provocative when it is casted in roles typically reserved for the 'normal', and suffers under these paradigms in relation to both film and theatre. I will approach these issues by an initial attempt to define the terms that characterize the field – including concepts as 'abnormality', 'disability' and the 'freak'-phenomenon – and discuss these in light of their specific contemporary societies. My scientific method is historiographical, as a thorough understanding of the examples I have chosen to focus on involves the reception of them, based on their contemporary ethical conditions. To be able to discuss the subject matter metaphorically, I will imply theory concerning theatricality, and the relation between performer and audience. My historical backdrop begins with the development of the american sideshow, from the development of the dime museums of the 19 th century to the main tendencies in modern sideshows at Coney Island, New York 'Freak' as term went through a significant shift in the 1960s, when subcultures connected to musical genres as psychedelia, prog rock and garage rock adopted the concept as a positive definition. Despite this fact, there still exists prejudist attitudes in contemporary performing arts. This is very apparent in one of my main examples, the staging of an adaptation of Tod Brownings film Freaks (1932). -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

The Problem Body Projecting Disability on Film

The Problem Body The Problem Body Projecting Disability on Film - E d i te d B y - Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotic’ T h e O h i O S T a T e U n i v e r S i T y P r e ss / C O l U m b us Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The problem body : projecting disability on film / edited by Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotic´. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1124-3 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9222-8 (cd-rom) 1. People with disabilities in motion pictures. 2. Human body in motion pictures. 3. Sociology of disability. I. Chivers, Sally, 1972– II. Markotic´, Nicole. PN1995.9.H34P76 2010 791.43’6561—dc22 2009052781 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1124-3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9222-8) Cover art: Anna Stave and Steven C. Stewart in It is fine! EVERYTHING IS FINE!, a film written by Steven C. Stewart and directed by Crispin Hellion Glover and David Brothers, Copyright Volcanic Eruptions/CrispinGlover.com, 2007. Photo by David Brothers. An earlier version of Johnson Cheu’s essay, “Seeing Blindness On-Screen: The Blind, Female Gaze,” was previously published as “Seeing Blindness on Screen” in The Journal of Popular Culture 42.3 (Wiley-Blackwell). Used by permission of the publisher. Michael Davidson’s essay, “Phantom Limbs: Film Noir and the Disabled Body,” was previously published under the same title in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Volume 9, no. -

The Dark Side of Hollywood

TCM Presents: The Dark Side of Hollywood Side of The Dark Presents: TCM I New York I November 20, 2018 New York Bonhams 580 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022 24838 Presents +1 212 644 9001 bonhams.com The Dark Side of Hollywood AUCTIONEERS SINCE 1793 New York | November 20, 2018 TCM Presents... The Dark Side of Hollywood Tuesday November 20, 2018 at 1pm New York BONHAMS Please note that bids must be ILLUSTRATIONS REGISTRATION 580 Madison Avenue submitted no later than 4pm on Front cover: lot 191 IMPORTANT NOTICE New York, New York 10022 the day prior to the auction. New Inside front cover: lot 191 Please note that all customers, bonhams.com bidders must also provide proof Table of Contents: lot 179 irrespective of any previous activity of identity and address when Session page 1: lot 102 with Bonhams, are required to PREVIEW submitting bids. Session page 2: lot 131 complete the Bidder Registration Los Angeles Session page 3: lot 168 Form in advance of the sale. The Friday November 2, Please contact client services with Session page 4: lot 192 form can be found at the back of 10am to 5pm any bidding inquiries. Session page 5: lot 267 every catalogue and on our Saturday November 3, Session page 6: lot 263 website at www.bonhams.com and 12pm to 5pm Please see pages 152 to 155 Session page 7: lot 398 should be returned by email or Sunday November 4, for bidder information including Session page 8: lot 416 post to the specialist department 12pm to 5pm Conditions of Sale, after-sale Session page 9: lot 466 or to the bids department at collection and shipment. -

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

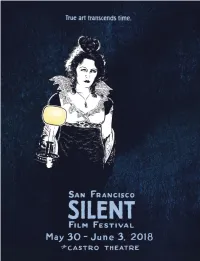

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2.