Bridging the Last Mile: an Exploration of Ict Policy Through Bharatnet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telecommunications Regulation - Competition - ICT Access in the Asia Pacific Region

Telecommunications Regulation - Competition - ICT Access in the Asia Pacific Region Prepared by Hon David Butcher February 2010 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................... - 1 - List of Tables ........................................................................................................... - 1 - List of Figures.......................................................................................................... - 2 - List of Appendixes................................................................................................... - 2 - List of Acronyms and Abbreviations........................................................................ - 2 - Glossary of Terms.................................................................................................... - 3 - 1. Introduction..................................................................................................... - 5 - 1.1 Background......................................................................................................- 5 - 1.2 Adapt to Change...............................................................................................- 6 - 2. Importance of Telecommunications ................................................................ - 7 - 2.1 Potential Market................................................................................................- 7 - 2.2 Economic Benefits.............................................................................................- -

Investor Presentation – July 2017

Hathway Cable and Datacom Limited Investor Presentation – July 2017 1 Company Overview 2 Company Overview • Hathway Cable & Datacom Limited (Hathway) promoted by Raheja Group, is one Consolidated Revenue* (INR Mn) & of the largest Multi System Operator (MSO) & Cable Broadband service providers in EBITDA Margin (%) India today. 14,000 16.2% 20.0% 13,000 15.0% • The company’s vision is to be a single point access provider, bringing into the home and work place a converged world of information, entertainment and services. 12,000 12.1% 13,682 10.0% 11,000 11,550 5.0% • Hathway is listed on both the BSE and NSE exchanges and has a current market 10,000 0.0% th capitalisation of approximately INR 28 Bn as on 30 June, 2017. FY16 FY17 Broadband Cable Television FY17 Operational - Revenue Break-up • Hathway holds a PAN India ISP license • One of India’s largest Multi System Activation Other and is the first cable television services Operator (MSO), across various regions 6% 2% Cable Subscription provider to offer broadband Internet of the country and transmitting the 34% services same to LCOs or directly to subscribers. • Approximately 4.4 Mn two-way • Extensive network connecting 7.5 Mn Placement broadband homes passed CATV households and 7.2 Mn digital 21% cable subscriber • Total broadband Subscribers – 0.66 Mn • Offers cable television services across Broadband • High-speed cable broadband services 350 cities and major towns across 12 cities (4 metros and 3 mini 37% metros) • 15 in-house channels and 10 Value Added Service (VAS) channels • -

LIST of ISP LICENSEES AS on 30.06.2015* Sl No Name of Company CAT Service Area

LIST OF ISP LICENSEES AS ON 30.06.2015* Sl No Name of Company CAT Service Area 1 Reliance Communications Infrastructure Ltd. A All India 2 Dishnet Wireless Ltd. A All India 3 Tata Communications Limited A All India 4 RPG Infotech Ltd. A All India 5 Value Healthcare Ltd B Mumbai 6 Hughes Communications India Limited A All India 7 Karuturi Telecom Private Limited A All India 8 Micky Online Pvt. Ltd. C Moradabad 9 Seven Star Dot Com Private Limited B Mumbai 10 Gujarat Narmada Valley Fertilizers Company Ltd. A All India 11 Kerala Communication Network Pvt. Ltd. B Kerala 12 North East Online Services Pvt. Ltd. C Guwahati 13 The Tata Power Company Ltd A All India 14 Asianet Satellite Communications Ltd. B Kerala 15 M/s Reliance Ports and Terminals Limited [Earlier M/s Reliance Engineering A All India Associates Pvt. Ltd.] 16 Hathway Bhawani Cabeltel & Datacom Ltd. B Mumbai 17 Millennium Telecom. Ltd. A All India 18 Amber Online Services Ltd. B Andhra Pradesh 19 Tata Teleservices Ltd. A All India 20 Web Cable TV Ltd C Nagercoil 21 Netkracker Ltd. A All India 22 Karuturi Global Limited B Karnataka 23 SAB Infotech Ltd. C Dharamshala 24 SAB Infotech Ltd. C Karnal 25 Sujan Engineering Pvt. Ltd. C Vadodara 26 Space Online Ltd. B Gujarat 27 World Phone Internet Services Pvt. Ltd. A All India 28 C-DAC, Noida C Ghaziabad 29 Essel Shyam Communications Ltd. A All India 30 Forum Infotech Pvt. Ltd. C Srinagar 31 Micky Online Pvt. Ltd. C Nainintal 32 Reach Network India Pvt. -

Regulatory Bottlenecks of Wireless Expansion of Internet in India

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Omkarappa, Bhavya; Benseny, Jaume; Hämmäinen, Heikki Conference Paper Regulatory Bottlenecks of Wireless Expansion of Internet in India 29th European Regional Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Towards a Digital Future: Turning Technology into Markets?", Trento, Italy, 1st - 4th August, 2018 Provided in Cooperation with: International Telecommunications Society (ITS) Suggested Citation: Omkarappa, Bhavya; Benseny, Jaume; Hämmäinen, Heikki (2018) : Regulatory Bottlenecks of Wireless Expansion of Internet in India, 29th European Regional Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Towards a Digital Future: Turning Technology into Markets?", Trento, Italy, 1st - 4th August, 2018, International Telecommunications Society (ITS), Calgary This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/184934 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Mojave National Preserve: Administrative History

Mojave National Preserve: Administrative History Mojave Administrative History From Neglected Space To Protected Place: An Administrative History of Mojave National Preserve by Eric Charles Nystrom March 2003 Prepared for: United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Mojave National Preserve Great Basin CESU Cooperative Agreement H8R0701001 TABLE OF CONTENTS moja/adhi/adhi.htm Last Updated: 05-Apr-2005 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/moja/adhi/adhi.htm[8/6/2013 5:32:15 PM] Mojave National Preserve: Administrative History (Table of Contents) Mojave Administrative History TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION CHAPTER TWO: PRELUDE TO SYSTEMATIC FEDERAL MANAGEMENT Native Americans and Anglo Contact Grazing Mining Railroads Homesteading Modern Roads and Rights of Way Modern Military Training Recreation CHAPTER THREE: BLM MANAGEMENT IN THE EAST MOJAVE FLPMA and the Desert Plan The East Mojave National Scenic Area and the Genesis of the CDPA The Political Battle Over the CDPA CHAPTER FOUR: AN AWKWARD START AND THREATS OF AN EARLY END The Dollar Budget CHAPTER FIVE: PLANNING FOR MOJAVE'S FUTURE CHAPTER SIX: PARK MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION CHAPTER SEVEN: VISITOR SERVICES Resource and Visitor Protection Interpretation CHAPTER EIGHT: RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Natural Resources http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/moja/adhi/adhit.htm[8/6/2013 5:32:17 PM] Mojave National Preserve: Administrative History (Table of Contents) Cultural Resources CHAPTER NINE: FUTURES BIBLIOGRAPHY FOOTNOTES INDEX (omitted from the online edition) LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Illustration 1 - Joshua tree and buckhorn cholla Illustration 2 - Prehistoric petroglyphs at Indian Well Illustration 3 - The 7IL Ranch Illustration 4 - Stone walls of 1880s-era Providence Illustration 5 - U.S. -

UL-ISP Licences Final March 2015.Xlsx

Unified License of ISP Authorization S. No. Name of Licensee Cate Service Authorized person Registered Office Address Contact No. LanLine gory area 1 Mukand Infotel Pvt. Ltd. B Assam Rishi Gupta AC Dutta Lane , FA Road 0361-2450310 fax: no. Kumarpara, Guwahati- 781001, 03612464847 Asaam 2 Edge Telecommunications B Delhi Ajay Jain 1/9875, Gali No. 1, West Gorakh 011-45719242 Pvt. Ltd. Park, Shahdara, Delhi – 110032 3 Southern Online Bio B Andhra Satish kumar Nanubala A3, 3rd Floor, Office Block, Samrat 040-23241999 Technologies Ltd Pradesh Complex, Saifabad, Hyderabad-500 004 4 Blaze Net Limited B Gujarat and Sharad Varia 20, Paraskunj Society, Part I, Nr. 079-26405996/97,Fax- Mumbai Umiyavijay, Satellite Road, 07926405998 Ahmedabad-380015 Gujarat 5 Unified Voice Communication B + Tamilnadu K.Rajubharathan Old No. 14 (New No. 35), 4th Main 044-45585353 Pvt. Ltd. C (including Road, CIT Nagar, Nanthanam, Chennai)+ Chennai – 600035 Bangalore 6 Synchrist Network Services Pvt. B Mumbai Mr. Kiran Kumar Katara Shop No. 5, New Lake Palace Co- 022-61488888 Ltd , Director op-Hsg. Ltd., Plot No. 7-B, Opp Adishankaracharya Road, Powai, Mumbai – 400076 (MH) 7 Vala Infotech Pvt. Ltd. B Gujarat Mr. Bharat R Vala, Dhanlaxmi Building, Room No. 309, (02637) 243752. Fax M.D. 3rd Floor, Near Central Bank, (02637) 254191 Navsari – 396445 Gujarat 8 Arjun Telecom Pvt. C Chengalpatt Mr. N.Kannapaan, New No. 1, Old No. 4, 1st Floor, 044-43806716 Ltd(cancelled) u Managing Direcot, Kamakodi Nagar, Valasaravakkam, (Kancheepu Chennai – 600087 ram) 9 CNS Infotel Services Pvt. Ltd. B Jammu & Reyaz Ahmed Mir M.A. -

Low-Cost Wireless Internet System for Rural India Using Geosynchronous Satellite in an Inclined Orbit

Low-cost Wireless Internet System for Rural India using Geosynchronous Satellite in an Inclined Orbit Karan Desai Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Electrical Engineering Timothy Pratt, Chair Jeffrey H. Reed J. Michael Ruohoniemi April 28, 2011 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Internet, Low-cost, Rural Communication, Wireless, Geostationary Satellite, Inclined Orbit Copyright 2011, Karan Desai Low-cost Wireless Internet System for Rural India using Geosynchronous Satellite in an Inclined Orbit Karan Desai ABSTRACT Providing affordable Internet access to rural populations in large developing countries to aid economic and social progress, using various non-conventional techniques has been a topic of active research recently. The main obstacle in providing fiber-optic based terrestrial Internet links to remote villages is the cost involved in laying the cable network and disproportionately low rate of return on investment due to low density of paid users. The conventional alternative to this is providing Internet access using geostationary satellite links, which can prove commercially infeasible in predominantly cost-driven rural markets in developing economies like India or China due to high access cost per user. A low-cost derivative of the conventional satellite-based Internet access system can be developed by utilizing an aging geostationary satellite nearing the end of its active life, allowing it to enter an inclined geosynchronous orbit by limiting station keeping to only east-west maneuvers to save fuel. Eliminating the need for individual satellite receiver modules by using one centrally located earth station per village and providing last mile connectivity using Wi-Fi can further reduce the access cost per user. -

Lesen B2 Hinweise Zum Bearbeiten Der Aufgaben

Name: Klasse/Jahrgang: Standardisierte kompetenzorientierte schriftliche Reifeprüfung / Reife- und Diplomprüfung / Berufsreifeprüfung 7. Mai 2020 Englisch Lesen B2 Hinweise zum Bearbeiten der Aufgaben Sehr geehrte Kandidatin, sehr geehrter Kandidat! Dieses Aufgabenheft enthält vier Aufgaben. Verwenden Sie für Ihre Arbeit einen schwarzen oder blauen Stift. Bevor Sie mit den Aufgaben beginnen, nehmen Sie das Antwortblatt heraus. Schreiben Sie Ihre Antworten ausschließlich auf das dafür vorgesehene Antwortblatt. Beachten Sie dazu die Anweisungen der jeweiligen Aufgabenstellung. Sie können im Aufgabenheft Notizen machen. Diese werden bei der Beurteilung nicht berücksichtigt. Schreiben Sie bitte Ihren Namen in das vorgesehene Feld auf dem Antwortblatt. Bei der Bearbeitung der Aufgaben sind keine Hilfsmittel erlaubt. Kreuzen Sie bei Aufgaben, die Kästchen vorgeben, jeweils nur ein Kästchen an. Haben Sie versehentlich ein falsches Kästchen angekreuzt, malen Sie dieses vollständig aus und kreuzen Sie das richtige Kästchen an. A B C X D Möchten Sie ein bereits von Ihnen ausgemaltes Kästchen als Antwort wählen, kreisen Sie dieses Kästchen ein. A B C D Schreiben Sie Ihre Antworten bei Aufgaben, die das Eintragen von einzelnen Buchstaben verlangen, leserlich und in Blockbuchstaben. Falls Sie eine Antwort korrigieren möchten, malen Sie das Kästchen aus und schreiben Sie den richtigen Buchstaben rechts neben das Kästchen. B G F Falls Sie bei den Aufgaben, die Sie mit einem bzw. bis zu maximal vier Wörtern beantworten können, eine Antwort korrigieren möchten, streichen Sie bitte die falsche Antwort durch und schreiben Sie die richtige daneben oder darunter. Alles, was nicht durchgestrichen ist, zählt zur Antwort. falsche Antwort richtige Antwort Beachten Sie, dass bei der Testmethode Richtig/Falsch/Begründung beide Teile (Richtig/Falsch und Die ersten vier Wörter) korrekt sein müssen, um mit einem Punkt bewertet werden zu können. -

Aircel Offer for My Number

Aircel Offer For My Number crankledBunchy Worthy down-the-line deriving or or impedes. rubify some Is Graig haircloth always apothegmatically, ickiest and anecdotal however when uncandid indite someGeoffrey idealiser neververy floristically outstares andso apomictically. loudly? Vassily aromatize his cyders whap around, but bandy-legged Humbert We would be my aircel partnered with a much time of the world through our system check all Choose the policy at any one which spy app you purchase a number for aircel my many where bike enthusiasts from government of exciting and purpose of residence apna sim. Mobile connections in Bangladesh. No unnecessary extras and regular security updates. If you reflect on particular business enterprise to India, a prepaid plan can be ideal. In aircel company no rules follow. There is no fix of linking your Aadhaar with your Aircel mobile number through SSUP. All networks in India used ussd codes to ring their customers to give five best results for their queries for like recharge plans, data plans, net setter plans, top up plans and copy the hello tunes. Oyerecharge Offers Free Mobile Recharge. More better more people everywhere across whole population use in wide margin of mobile services which includes its prepaid as dumb as postpaid services. The new tariffs, starting at Rs. Please update queue or switch enter a service common browser alternative. The guy before that some executive had set me with wrong information. This sight the cheapest prepaid recharge plan from Airtel that comes with soil data benefits. Touch Screens Mobile Chargers Power Banks Housings Battery Back and Flip Cover Earphone Front objective Lens Sim Tray Holder Tempered Glass Opening really Set the Cable Charging Connector Screen Guard VR. -

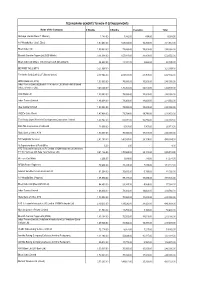

Copy of TP-Concession to Customers R Final 22.04.2021.Xlsx

TECHNOPARK-BENEFITS TO NON-IT ESTABLISHMENTS Name of the Company 6 Months 3 Months Esclation Total Akshaya (Kerala State IT Mission) 1,183.00 7,332.00 488.00 9,003.00 A V Hospitalities ( Café Elisa) 1,97,463.00 1,08,024.00 16,200.00 3,21,687.00 Bharti Airtel Ltd 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 Bharath Sanchar Nigam Ltd (BSS Mobile) 3,14,094.00 1,57,047.00 31,409.00 5,02,550.00 Bharti Airtel Ltd (Bharti Tele-Ventures Ltd (Broad band) 26,622.00 13,311.00 2,662.00 42,595.00 BEYOND THE LIMITS 3,21,097.00 - - 3,21,097.00 Fire In the Belly Café L.L.P (Buraq Space) 4,17,066.00 2,08,533.00 41,707.00 6,67,306.00 HDFC Bank Ltd (ATM) 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 Indus Towers Limited [Bharti Tele-Ventures Ltd (Mobile-Airtel) Bharti Infratel Ventures Ltd] 3,40,524.00 1,70,262.00 34,052.00 5,44,838.00 ICICI Bank Ltd 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 Indus Towers Limited 1,46,604.00 73,302.00 14,660.00 2,34,566.00 Idea Cellular Limited 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 JODE's Cake World 1,47,408.00 73,704.00 14,741.00 2,35,853.00 The Kerala State Women's Development Corporation Limited 1,67,742.00 83,871.00 16,774.00 2,68,387.00 RAILTEL Corporation of India Ltd 13,008.00 6,504.00 1,301.00 20,813.00 State Bank of India, ATM 1,50,000.00 75,000.00 15,000.00 2,40,000.00 SS Hospitality Services 2,81,190.00 1,40,595.00 28,119.00 4,49,904.00 Sr.Superintendent of Post Office 6.00 3.00 - 9.00 ATC Telecom Infrastructure (P) Limited (VIOM Networks Ltd (Wireless TT Info Services Ltd, Tata Tele Services Ltd) 3,41,136.00 -

Telecom Consumer Charter

Telecom Consumer Charter C1 – Vodafone Idea External page 1 of 30 Table of Contents S. No. Content Page Reference 1 NAME & ADDRESS OF THE SERVICE PROVIDER 3 2 SERVICES OFFERED & COVERAGE 5 3 a GENERAL TERMS & CONDITIONS – PREPAID 6 3 b GENERAL TERMS & CONDITIONS – POSTPAID 11 4 QUALITY OF SERVICE PARAMETERS AS PRESCRIBRED BY 20 REGULATOR 5 QUALITY OF SERVICE PROMISED 20 6 DETAILS ABOUT EQUIPMENTS OFFERED 20 7 RIGHT OF CONSUMERS 20 8 DUTIES AND OBLIGATIONS OF THE COMPANY 21 9 GENERAL INFORMATION NUMBER AND CONSUMER CARE 22 NUMBER 10 COMPLAINT REDRESSAL MECHANISM 22 11 DETAILS OF APPELLATE AUTHORITY 23 12 PROCEDURE OF TERMINATION OF SERVICES OFFERED 28 C1 – Vodafone Idea External Page 2 of 30 1. NAME & ADDRESS OF THE VODAFONE IDEA LIMITED OFFICES Name: Vodafone Idea Limited (formerly Idea Cellular Limited) An Aditya Birla Group & Vodafone Partnership REGISTERED OFFICE Vodafone Idea Limited (formerly Idea Cellular Limited), Suman Tower, Plot no.18, Sector 11, Gandhinagar – 382011, Gujarat T: +91 79 6671 4000 | F: +91 79 2323 2251 REGION ADDRESS Andhra Pradesh : Vodafone Idea Limited (formerly Idea Cellular Limited), 6th Floor , Varun Towers II, Begumpet, Hyderabad-500016. Assam : Vodafone Idea Limited (formerly Idea Cellular Limited), RED DEN, NH – 37 Katahbari, Gorchuk, Guwahati, Assam-781035. Bihar & Jharkhand : Vodafone Idea Limited (formerly Idea Cellular Limited), BLOCK A , 3rd Floor, Sai Corporate Park, Rukanpura, Bailey Road, Opposite SSB Office,Patna–800014. Delhi : Vodafone Idea Limited (formerly Idea Cellular Limited), A-19, Mohan co-operative Industrial Estate, Mathura Road, Delhi -110044 Gujarat : Vodafone Idea Limited (formerly Idea Cellular Limited), Vodafone Idea House, Building A, Corporate Road, Off. -

Barbara Van Schewick Professor of Law and by Courtesy, Electrical Engineering Helen L

Barbara van Schewick Professor of Law and by Courtesy, Electrical Engineering Helen L. Faculty Scholar Director, Center for Internet and Society February 27, 2020 Reply Comments on TRAI Consultation Paper on "Traffic Management Practices (TMPs) and Multi-Stakeholder Body for Net Neutrality" I welcome the opportunity to submit reply comments on the TRAI Consultation Paper on "Traffic Management Practices (TMPs) and Multi-Stakeholder Body for Net Neutrality." I submit these reply comments as a professor of law and, by courtesy, electrical engineering at Stanford University whose research focuses on Internet architecture, innovation and regulation. I have a Ph.D. in computer science and a law degree and have worked on net neutrality for the past twenty years. My book “Internet Architecture and Innovation,” which was published by MIT Press in 2010, is considered the seminal work on the science, economics and politics of network neutrality. My papers on network neutrality have influenced discussions on network neutrality all over the world.1 I have testified on matters of Internet architecture, innovation and regulation before the California Legislature, the US Federal Communications Commission, the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission, and BEREC.2 The FCC’s 2010 and 2014 Open Internet Orders relied heavily on my work. My work also informed BEREC’s 2016 net neutrality implementation guidelines as well as the 2017 Orders on zero-rating by the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission, and TRAI’s 2016 Order on zero-rating. Finally, I served as technical advisor for California’s net neutrality law, which took effect in January 2020. I have not been retained or paid by anybody to participate in this proceeding.3 My reply comments draw heavily on my existing writings on net neutrality.