Activating Mason City a Bicycle & Pedestrian Master Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caledonia State Park

History A Pennsylvania Recreational Guide for Caledonia State Park Thaddeus Stevens 1792-1868 run-away slaves north to Greenwood, just west of the park, Caledonia State Park The 1,125-acre Caledonia State Park is in Adams and Called the Great Commoner, Thaddeus Stevens was an to meet the next conductor on the journey to freedom. For Franklin counties, midway between Chambersburg and abolitionist, radical republican and was one of the most this, and Stevens’ tireless fight for equal rights, Caledonia Gettysburg along the Lincoln Highway, US 30. effective and powerful legislators of the Civil War era. Some State Park is a Path of Freedom site. The park is nestled within South Mountain, the northern historians consider Stevens the de facto leader of the United During the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil terminus of the well-known Blue Ridge Mountain of States during the presidency of Andrew Johnson. Stevens War, the confederate cavalry of General J.A. Early raided Maryland and Virginia. Within South Mountain there are became the third person in American history to be given throughout southern Pennsylvania but followed a policy four state parks and 84,000 acres of state forest land waiting the privilege of lying in state in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, to destroy no private property or industry. The cavalry to be explored and enjoyed. The soils on either side of following Senator Henry Clay and President Lincoln. burned and pillaged Caledonia. Early explained his actions, South Mountain are ideal for fruit production, proven by the Born in Caledonia County, Vermont, Stevens would face “Mr. -

Glen Echo Park - Then and Now Carousel Was One of the First to Be Sold, but a Fundraising Major Improvements to the Park

The Bakers then began efforts to transfer some of the Park’s Finally in 1999 the federal, state and county governments attractions to other Rekab, Inc., properties and to sell the jointly funded an eighteen million dollar renovation of the remainder of the rides and attractions. The Dentzel Spanish Ballroom and Arcade buildings as well as many other Glen Echo Park - Then and Now carousel was one of the first to be sold, but a fundraising major improvements to the park. drive organized by Glen Echo Town councilwoman Nancy Long, provided money to buy back the Park’s beloved In 2000, the National Park Service entered into a cooperative carousel. agreement with Montgomery County government to manage the park’s programs. Montgomery County set up a non-profit organization called the Glen Echo Park Partnership for Arts and Culture, Inc. The Partnership is charged with managing and maintaining Park facilities, managing the artist-in- residence, education and social dance programs, fundraising and marketing. The National Park Service is responsible for historical interpretation, safety, security, resource protection and grounds maintenance. Glen Echo Park Today For well over one hundred years Glen Echo Park has been delighting the people who come to study, to play, and to enjoy the park’s own special charms. Let’s stroll through Glen Echo Park’s memories, and then see what the Park is offering you, your family, and your neighbors d Glen Echo Park retains many of its old treasures. The Chautauqua Tower, the Yellow Barn, the Dentzel Carousel, Glen Echo was chosen as the assembly site by the recently the Bumper Car Pavilion, the Spanish Ballroom, the Arcade formed Chautauqua Union of Washington, D.C. -

The Trolley Park News

THE TROLLEY PARK NEWS Aug.-Oct. 1980 Oregon Electric Railway Historical Society Bulletin Vol. 21, No’s 8, 9 & 10 midnight, the lot had been weeded down to the five best PCCs. The two returned on the morrow and made their final selection, No. 1159. While Paul waited for the PCC to be brought over to the Metro Center for loading (there was no suitable crane in the Geneva Car House), Charles was taken on a brief training “run” inside the barn in a similar PCC. His introduction to the starting and stopping characteristics of these cars is a vivid memory; the instructor accelerated flat out toward the back wall of the carbarn, stopping "on a dime" just before creating a new bay. Charles says the 1930s tech- nology of the PCC remains very impressive. Muni PCC 1159 was put on the rails at Glenwood on Sept 23, 1980, the day after two OERHS members returned from an arduous trip to San Francisco to retrieve it (Oregonian photo). No. 1159 had been loaded by 3 p.m., but could not be moved when the trailer proved to be too short. round trip to get the car. The PCC Although the front wheels were 1159 was a “Will Call” was hauled on Paul's specially firmly held in place by welded designed trolley trailer. A rented chocks, the rear truck was free to Trolley Hertz 10-speed diesel tractor move slightly owing to the provided the power. articulated design of Paul's trailer. he newest addition to the The rear wheels nearly slipped off T OERHS collection is PCC No. -

May Challenge

Create Your Own Amusement Park Challenge What is the ultimate combination of physics and fun? An amusement park, of course! A little history According the Guinness Book of World Records: “Bakken, located in Klampenborg, North of Copenhagen (Denmark), opened in 1583 and is currently the oldest operating amusement park in the world. The park claims to have over 150 attractions, including a wooden roller coaster built in 1932. In medieval Europe, most major cities featured what is the origin of the amusement park: the pleasure gardens. These gardens featured live entertainment, fireworks, dancing, games and some primitive amusement rides. Most closed down during the 1700's, but Bakken is the only one to survive.” Lots of towns, both big and small, in the United States had some sort of amusement park in the late 1800’s to early-mid 1900’s. Many started out as trolley parks created by streetcar companies to give people a reason to use their services on weekends. These parks had picnic areas and pavilions to hold dances and concerts. Many evolved over time to include swimming pools, carousels, roller coasters, Ferris wheels, and boat rides becoming the modern amusement park. It is reported there were between 1,500 - 2,000 amusement parks in the United States by 1919. Today there are more than 10,000 in the United States alone! There are still some of these historical parks still in existence like Knoebels Amusement Resort in Pennsylvania. Originally known as Knoebels Grove, this park opened in 1926 and still family owned. Other parks, such as Hershey Park in Pennsylvania, are internationally know today but started as trolley park in 1907. -

Guide to the Willow Grove Park Association Collection

Guide to the Willow Grove Park Association Collection NMAH.AC.0362 Vanessa Broussard-Simmons 1989 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Willow Grove Park Association Collection NMAH.AC.0362 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: Willow Grove Park Association Collection Identifier: NMAH.AC.0362 Date: 1910, 1929 Creator: Willow Grove Park Association (Creator) National Museum of American History (U.S.). Division of Community Life (Collector) Cayton, Howard (Collector) -

Cumberland County Historical Society (717) 249-7610; 21 North Pitt

Staff Roster Board Roster Jason Illari – Executive Director David Smith– President Beverly Bone – Archives & Library Assistant Ginny Mowery – VP/Historic Properties Chair Harriet Carn – Environmental Services Assistant David Gority – Treasurer/Finance Chair Cara Curtis – Archives & Library Manager Sherry Kreitzer – Secretary Peggy Huffman – Museum Assistant Curator Tita Eberly Kim Laidler – HOH Manager Pat Ferris – Museum Chair Barbara Landis – Archives & Library CIIS Specialist Robin Fidler – Education Chair Kurt Lewis – Historic Properties Coordinator Robert Grochalski – Awards & Scholarships Chair Lynda Mann – Programming & Membership Coordinator Ann K. Hoffer – Development Chair/TMH Chair Matthew March – Education Curator Linda Humes – Program/Membership Chair Mary March – Collections Manager Larry Keener-Farley – Publications Chair Debbie Miller – Archives & Library Collections Specialist Kristin Senecal – Archives & Library Chair Robert Schwartz – Archives & Library Research Specialist Kate Theimer Richard Tritt – Archives & Library Photograph Curator E.K. Weitzel Lindsay Varner – Heart & Soul Project Manager Dr. André Weltman Blair Williams – Archives & Library Media Specialist Lucy Wolf – Bookkeeper Rachael Zuch – Museum Curator Cumberland County Historical Society (717) 249-7610; 21 North Pitt Street, Carlisle PA 17013 Monday 4 PM – 8 PM; Tuesday – Friday 10 AM – 4 PM; Saturday 10 AM – 2 PM Two Mile House (717) 249-7610; 1189 Walnut Bottom Road, Carlisle PA 17015 History on High – The Shop (717) 249-1626; 33 West High Street, Carlisle PA 17013 Sun. & Mon. Closed; Tuesday – Friday 10 AM – 5 PM; Saturday 10 AM – 2 PM G.B. Stuart History Workshop; 29 West High Street, Carlisle PA 17013 Thursday & Friday 10 AM-4 PM; Saturday 10 AM – 2 PM Cumberland Valley Visitors Center; 33 West High Street, Carlisle PA 17013 Sun. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) • United States Department of the Interior \ National Park Service National Register of Historic Places OCT23 Registration Form •RV This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations fc individual properties See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration For (National R< gister Bulletin 16A). CorE.pJ«J;$f$cK item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply •tbfl projwrty-being docume*rTf6a7*8~riler "N/A" for 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instruction. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name: Palace Amusements other names/site number: Palace Merry-Go-Round and Ferris Wheel Building 2. Location street and number: 201 -207 Lake Avenue N/A not for publication city or town: Asbury Park City N/A vicinity state: New Jersey county: Monmouth County zip code: 07712 3. State/Federal/Tribal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _j meets ... does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Treasures in Plain Sight

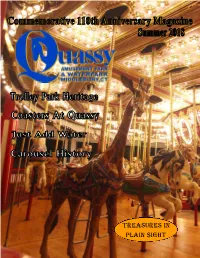

Treasures In Plain Sight 110th Anniversary Magazine Cover photo: The Grand Carousel at Quassy Amusement Park. The 50-foot ride arrived at the park in March of 1990 and is housed in one of the oldest structures on the property: a 1927 roundhouse. The current carousel replaced one that operated at Quassy for decades, which was auctioned in the fall of 1989. F e a t u r e S t o r i e s 3 Trolley Park Heritage Once owned an operated by an electrified rail line (trolley), Quassy is one of less than a dozen remaining trolley parks in the nation. Prior to the Great Depression of 1929, there were more than 1,000 such amusement parks. 6 The Coasters At Quassy Roller coasters are considered the cornerstone of many modern-day amusement parks. Quassy’s history with roller coasters dates back to 1952 when it introduced its first coaster. 12 Just Add Water Quassy entered the waterpark business in 2003 and hasn’t looked back since. Splash Away Bay has grown in leaps and bounds. 27 Treasures In Plain Sight Humpty Dumpty sat on a …. In this case a rooftop. Don’t overlook some of the treasures at Quassy Amusement Park that are right before your very eyes! Other Stories Inside... Carousels At Quassy Date Back To Early Years Billy’s Back In Town! He Went Full Circle Quassy’s Rides: A Mix Of The Old And New All Aboard The Refurbished Quassy Express All stories and photos in this publication are the property of Quassy Amusement Park Meet The Quassy Team and may not be reproduced without written permission. -

Washington Luna Park, Early 1900'S, Arlington, Virginia. Arial Vew of The

Arlington County Central Library Washington Luna Park, early 1900's, Arlington, Virginia. Arlington County Arial vew of the Water Pollution Control Plant located in Arlington, Virginia. 44 ARLINGTON H ISTORICAL M AGA ZINE From Trolley Park to Sewage Treatment: Luna Park BY MARTY SUYDAM Sometimes Charley and I take a long walk around the perimeter of Ar lington Ridge. We walk south to the trail along side Four-Mile Run, then east to South Eads Street, then north on Eads. That last comer is now is part of the Arlington County sewage treatment facility, a very large, modem, waste processing operation that also includes drop-off locations for hazardous waste. In the early 1900's there was a 34-acre "trolley park", Luna Park, on that property. The trolley park got its name from the fact that it was located along an electric-powered inter-urban trolley line that provided easy, afford able transportation from Washington and Alexandria along the route of the old Georgetown-Alexandria canal. The original canal structures are gone, but the Washington Metrorail system now follows the canal's route. The location where the canal crossed over Four Mile run was the site of an explosive train wreck that occurred in 1885 where the canal, train tracks and wagon road (now US 1) intersected at the Four Mile run crossing. Trolley parks were the precursor to amusement parks and were fostered by the streetcar companies to make use of the transportation on weekends. The Washington Times recorded: 1 The normal fee for the round trip on the line was twenty-five cents but the railway offered a special rate of fifteen cents to entice park patrons from both the Washington and Alexandria terminals. -

Henry Lynn for in the Age of Steel: Oral Histories from Bethlehem Pennsylvania

This is an interview with Henry Lynn for In the Age of Steel: Oral Histories from Bethlehem Pennsylvania. The interview was conducted by Roger D. Simon on July 14, 1975 in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. 00:00:00 Simon: Henry Lynn at his home at Moravian House in Bethlehem, July 14, 1975. My name is Roger Simon. Mr. Lynn, tell me whereabouts that you were born and about when, if you will. Lynn: I was born out at 409 Church Street across from the Nisky Hill Cemetery. I was born the ninth of September in 1887. 00:00:59 Simon: Have you always lived in Bethlehem? Lynn: All my life. Simon: What was that neighborhood on Church Street like when you were a youngster? Lynn: Well, they were all homes, with the exception of a corner grocery store, but everything else was homes around the whole neighborhood. Simon: What kind of families lived around there then? Lynn: All people that worked at the Steel1, practically. Simon: What did your father do? Lynn: He worked at the Steel for—I don’t know how old he was when he left, but then he went into the meat business, had a meat market. Simon: Where was his meat market? Lynn: On 88 East Broad Street, one of the sections that’s torn down now. Simon: 88 East Broad Street. Was he a butcher? Lynn: Yeh. 1 Bethlehem Steel Simon: Was he an immigrant or was he born— Lynn: No, he was born here. Simon: Do you know what your family background is, where your people come from? Lynn: Well, I asked. -

The United States of Amusement by Udomdej Puenpa B.A. in Liberal English, May 2010, Rangsit University M.S in Library and Inform

The United States of Amusement by Udomdej Puenpa B.A. in Liberal English, May 2010, Rangsit University M.S in Library and Information Science, December 2016, Catholic University of America A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Exhibition Design May 19, 2019 Thesis directed by Andrea Hunter Dietz Assistance Professor of Exhibition Design Abstract The United States of Amusement This thesis proposal is presenting an exhibition about the evolution of amusement parks in the United States from the late 1890s until the present era, the late 2010s. The thesis will spell out the details of an exhibit that will show how amusement parks have impacted American culture, as well as how evolving technology has changed the amusement park industry. Starting as small businesses providing recreation and pleasure to local audiences, amusement parks evolved over the decades into sophisticated national corporations with a global reach. Yet this exhibit will also show that all the while, as technology improved and as old-time amusement parks gave way to larger modern theme parks, the goal remained the same: to leave the United States in a state of amusement. ii Table of Contents Abstract ii Table of Contents iii List of Figures v Introduction 1 Why Amusement Parks Matter 2 A Brief History 4 Exhibition contents 9 • Goals • Contents Design Strategies 13 Interpretive Strategies 15 Audiences 16 Site Selection 19 Precedents 22 Conclusion 25 Appendix I 28 iii Appendix II 32 Appendix III 39 iv List of Figures Figure 1. -

Kennyw Timeline Font Revise

MORE THAN FUN AND FRIES 1976 A History of Kennywood The Thunderbolt is named the “King of Coasters” by the New York Times. 1987 Kennywood is designated a National Historic Landmark 1815 1902 by the U.S. Department of the Charles Kenny purchases Kennywood builds its first roller 1936 Interior. the land that is the future coaster, the Figure Eight Noah’s Ark is 1991 Toboggan. (Nothing of this constructed at The Steel Phantom roller site of Kennywood. He The Monongahela Street mines coal on the land. remains now.) Kennywood, in coaster is built. It is the Railway Company merges the same year, 1950s–1970s fastest roller coaster in 1906 with the Pittsburgh Street coincidentally, With competition from Disney the world. Andrew McSwigan, Frederick Henninger, and Railway Company (PRC). At as the record- Land and other new “theme A.F. Megahan form the Pittsburg Kennywood 1758 this time, the trolley is an breaking St. parks,” Kennywood grows and Park Company and lease Kennywood from 2001 Pittsburgh is founded essential form of transporta- Patrick’s Day adapts in order to survive by PRC. Three and four generations later, The Steel Phantom is and named for British tion for those living in flood in building newer and bigger rides descendants of McSwigan and Henninger reconstructed as the statesmanWilliam Pitt. Pittsburgh’s newly expanding Pittsburgh. such as the Turnpike. suburbs and neighborhoods. (respectively) are still involved with the park. Phantom’s Revenge. ••••• 1750 1800 1850 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Kennywood enters 1755 1921 1995 1860s 1930–1935 a new century Across the The Jack Rabbit, 1941–1945 Lost Kennywood, which is Some of the Kenny Kennywood is as America’s Monongahela River Kennywood’s Kennywood gives based on Oakland’s Luna family’s land, known threatened by finest traditional from what is now oldest running free admission to amusement park from the early as “Kenny’s Grove,” the Great amusement park.