Wonderland Amusement Park Was a Sight to Behold. in a City Lit Only By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caledonia State Park

History A Pennsylvania Recreational Guide for Caledonia State Park Thaddeus Stevens 1792-1868 run-away slaves north to Greenwood, just west of the park, Caledonia State Park The 1,125-acre Caledonia State Park is in Adams and Called the Great Commoner, Thaddeus Stevens was an to meet the next conductor on the journey to freedom. For Franklin counties, midway between Chambersburg and abolitionist, radical republican and was one of the most this, and Stevens’ tireless fight for equal rights, Caledonia Gettysburg along the Lincoln Highway, US 30. effective and powerful legislators of the Civil War era. Some State Park is a Path of Freedom site. The park is nestled within South Mountain, the northern historians consider Stevens the de facto leader of the United During the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil terminus of the well-known Blue Ridge Mountain of States during the presidency of Andrew Johnson. Stevens War, the confederate cavalry of General J.A. Early raided Maryland and Virginia. Within South Mountain there are became the third person in American history to be given throughout southern Pennsylvania but followed a policy four state parks and 84,000 acres of state forest land waiting the privilege of lying in state in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, to destroy no private property or industry. The cavalry to be explored and enjoyed. The soils on either side of following Senator Henry Clay and President Lincoln. burned and pillaged Caledonia. Early explained his actions, South Mountain are ideal for fruit production, proven by the Born in Caledonia County, Vermont, Stevens would face “Mr. -

Glen Echo Park - Then and Now Carousel Was One of the First to Be Sold, but a Fundraising Major Improvements to the Park

The Bakers then began efforts to transfer some of the Park’s Finally in 1999 the federal, state and county governments attractions to other Rekab, Inc., properties and to sell the jointly funded an eighteen million dollar renovation of the remainder of the rides and attractions. The Dentzel Spanish Ballroom and Arcade buildings as well as many other Glen Echo Park - Then and Now carousel was one of the first to be sold, but a fundraising major improvements to the park. drive organized by Glen Echo Town councilwoman Nancy Long, provided money to buy back the Park’s beloved In 2000, the National Park Service entered into a cooperative carousel. agreement with Montgomery County government to manage the park’s programs. Montgomery County set up a non-profit organization called the Glen Echo Park Partnership for Arts and Culture, Inc. The Partnership is charged with managing and maintaining Park facilities, managing the artist-in- residence, education and social dance programs, fundraising and marketing. The National Park Service is responsible for historical interpretation, safety, security, resource protection and grounds maintenance. Glen Echo Park Today For well over one hundred years Glen Echo Park has been delighting the people who come to study, to play, and to enjoy the park’s own special charms. Let’s stroll through Glen Echo Park’s memories, and then see what the Park is offering you, your family, and your neighbors d Glen Echo Park retains many of its old treasures. The Chautauqua Tower, the Yellow Barn, the Dentzel Carousel, Glen Echo was chosen as the assembly site by the recently the Bumper Car Pavilion, the Spanish Ballroom, the Arcade formed Chautauqua Union of Washington, D.C. -

Activating Mason City a Bicycle & Pedestrian Master Plan

ACTIVATING MASON CITY A BICYCLE & PEDESTRIAN MASTER PLAN FEBRUARYJANUARY 2014 2014 e are grateful for the Mayor and City Council Project Advisory Committee Consulting Team collaboration and insight Eric Bookmeyer | Mayor Craig Binnebose RDG Planning & Design Wof the Project Steering Alex Kuhn Gary Christiansen Des Moines and Omaha Committee, without whom this Scott Tornquist Craig Clark www.RDGUSA.com document would not have been John Lee Matt Curtis WHKS & Co. possible. We especially appreciate Travis Hickey Angie Determan Jean Marinos Kelly Hansen Mason City, Iowa the wonderful support, friendship, www.WHKS.com professionalism, and patience of Janet Solberg Jim Miller Mason City’s great staff, including Brian Pauly Steven Van Steenhuyse, Brent City of Mason City Mark Rahm Trout, Tricia Sandahl, and Mark Steven Van Steenhuyse, AICP Tricia Sandahl Steven Schurtz Rahm. Director of Development Services Bill Stangler Brent Trout This plan complements the city’s Brent Trout | City Administrator Steven Van Steenhuyse previous planning initiatives Mark Rahm, PE | City Engineer and establishes a system of Tricia Sandahl | Planning & Zoning Manager improvements to create an even more active community. The Blue Zones Project® is a community “The last few years have resulted in a significant culture change well-being improvement initiative across our entire community and the Blue Zones Project® has designed to make healthy choices been a driving force in our River City Renaissance. It provided easier through permanent changes to the format for collaboration -

The Trolley Park News

THE TROLLEY PARK NEWS Aug.-Oct. 1980 Oregon Electric Railway Historical Society Bulletin Vol. 21, No’s 8, 9 & 10 midnight, the lot had been weeded down to the five best PCCs. The two returned on the morrow and made their final selection, No. 1159. While Paul waited for the PCC to be brought over to the Metro Center for loading (there was no suitable crane in the Geneva Car House), Charles was taken on a brief training “run” inside the barn in a similar PCC. His introduction to the starting and stopping characteristics of these cars is a vivid memory; the instructor accelerated flat out toward the back wall of the carbarn, stopping "on a dime" just before creating a new bay. Charles says the 1930s tech- nology of the PCC remains very impressive. Muni PCC 1159 was put on the rails at Glenwood on Sept 23, 1980, the day after two OERHS members returned from an arduous trip to San Francisco to retrieve it (Oregonian photo). No. 1159 had been loaded by 3 p.m., but could not be moved when the trailer proved to be too short. round trip to get the car. The PCC Although the front wheels were 1159 was a “Will Call” was hauled on Paul's specially firmly held in place by welded designed trolley trailer. A rented chocks, the rear truck was free to Trolley Hertz 10-speed diesel tractor move slightly owing to the provided the power. articulated design of Paul's trailer. he newest addition to the The rear wheels nearly slipped off T OERHS collection is PCC No. -

May Challenge

Create Your Own Amusement Park Challenge What is the ultimate combination of physics and fun? An amusement park, of course! A little history According the Guinness Book of World Records: “Bakken, located in Klampenborg, North of Copenhagen (Denmark), opened in 1583 and is currently the oldest operating amusement park in the world. The park claims to have over 150 attractions, including a wooden roller coaster built in 1932. In medieval Europe, most major cities featured what is the origin of the amusement park: the pleasure gardens. These gardens featured live entertainment, fireworks, dancing, games and some primitive amusement rides. Most closed down during the 1700's, but Bakken is the only one to survive.” Lots of towns, both big and small, in the United States had some sort of amusement park in the late 1800’s to early-mid 1900’s. Many started out as trolley parks created by streetcar companies to give people a reason to use their services on weekends. These parks had picnic areas and pavilions to hold dances and concerts. Many evolved over time to include swimming pools, carousels, roller coasters, Ferris wheels, and boat rides becoming the modern amusement park. It is reported there were between 1,500 - 2,000 amusement parks in the United States by 1919. Today there are more than 10,000 in the United States alone! There are still some of these historical parks still in existence like Knoebels Amusement Resort in Pennsylvania. Originally known as Knoebels Grove, this park opened in 1926 and still family owned. Other parks, such as Hershey Park in Pennsylvania, are internationally know today but started as trolley park in 1907. -

Amusementtodaycom

KINGS ISLAND’S 40th ANNIVERSARY – PAGES 19-22 TM Vol. 16 • Issue 3 JUNE 2012 Two traditional parks turn to Zamperla for thrill factor AirRace takes flight at Utah’s Lagoon Massive Black Widow swings into historic Kennywood Park FARMINGTON, Utah — Inspired by what they saw at Co- STORY: Scott Rutherford ney Island’s Luna Park last year, Lagoon officials called upon [email protected] Zamperla to create for them a version of the Italian ride manu- WEST MIFFLIN, Pa. — facturer’s spectacular AirRace attraction. Guests visiting Kennywood Just as with the proptype AirRace at Luna Park, Lagoon’s Park this season will find new ride replicates the thrill and sensations of an acrobatic air- something decidedly sinister plane flight with maneuvers such as banks, loops and dives. lurking in the back corner of Accommodating up to 24 riders in six four-seater airplane- Lost Kennywood. The park’s shaped gondolas, AirRace combines a six-rpm rotation with a newest addition to its impres- motor driven sweep undulation that provides various multi- sive ride arsenal is Black vectored sensations. The gondolas reach a maximum height of Widow, a Zamperla Giant 26 feet above the ground while ‘pilots’ feel the acceleration of Discovery 40 swinging pen- almost four Gs, both right-side-up and inverted. The over-the- dulum ride. shoulder restraint incorporated into the seats holds riders during Overlooking the the simulated flight, and with a minimum height requirement of final swoop turn of the just 48 inches, AirRace is one of Lagoon’s most accessible family Phantom’s Revenge and the thrill rides. -

Guide to the Willow Grove Park Association Collection

Guide to the Willow Grove Park Association Collection NMAH.AC.0362 Vanessa Broussard-Simmons 1989 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Willow Grove Park Association Collection NMAH.AC.0362 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: Willow Grove Park Association Collection Identifier: NMAH.AC.0362 Date: 1910, 1929 Creator: Willow Grove Park Association (Creator) National Museum of American History (U.S.). Division of Community Life (Collector) Cayton, Howard (Collector) -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 ^0"' fr uirr ilL UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________. TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Coney Island of the West AND/OR COMMON Coney Island LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER Lake Waconia CITY, TOWN -' is < CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Second Waconia _.VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Minnesota 27 Carver 019 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^-PRIVATE .^UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE X.SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT ?_IN PROCESS JLYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION has _NO rii'u'Kfe'd to nfcfflft^fiy state - dense foliage NAME Multiple (see continuation sheet - page 1 - for complete listing) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Registry of peeds - Carver County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER 205 East 4th Street CITY, TOWN TITLE Statewide Historic Sites Survey DATE 1975. —FEDERAL j£STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Minnesota Historical Society - Building 25, Fort Snelling CITY. TOWN STATE I St. Paul Minnesota DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The thirty-one acre Coney Island is located north one-half mile off shore of the City of Waconia in Lake Waconia. The physical dimensions of the island are as follows: along its East-West axis it is about 2000 feet long; along its North-South axis on the West end it is about 1200 feet across; and on the North-South axis on the East end it is about 650 feet across. -

Cumberland County Historical Society (717) 249-7610; 21 North Pitt

Staff Roster Board Roster Jason Illari – Executive Director David Smith– President Beverly Bone – Archives & Library Assistant Ginny Mowery – VP/Historic Properties Chair Harriet Carn – Environmental Services Assistant David Gority – Treasurer/Finance Chair Cara Curtis – Archives & Library Manager Sherry Kreitzer – Secretary Peggy Huffman – Museum Assistant Curator Tita Eberly Kim Laidler – HOH Manager Pat Ferris – Museum Chair Barbara Landis – Archives & Library CIIS Specialist Robin Fidler – Education Chair Kurt Lewis – Historic Properties Coordinator Robert Grochalski – Awards & Scholarships Chair Lynda Mann – Programming & Membership Coordinator Ann K. Hoffer – Development Chair/TMH Chair Matthew March – Education Curator Linda Humes – Program/Membership Chair Mary March – Collections Manager Larry Keener-Farley – Publications Chair Debbie Miller – Archives & Library Collections Specialist Kristin Senecal – Archives & Library Chair Robert Schwartz – Archives & Library Research Specialist Kate Theimer Richard Tritt – Archives & Library Photograph Curator E.K. Weitzel Lindsay Varner – Heart & Soul Project Manager Dr. André Weltman Blair Williams – Archives & Library Media Specialist Lucy Wolf – Bookkeeper Rachael Zuch – Museum Curator Cumberland County Historical Society (717) 249-7610; 21 North Pitt Street, Carlisle PA 17013 Monday 4 PM – 8 PM; Tuesday – Friday 10 AM – 4 PM; Saturday 10 AM – 2 PM Two Mile House (717) 249-7610; 1189 Walnut Bottom Road, Carlisle PA 17015 History on High – The Shop (717) 249-1626; 33 West High Street, Carlisle PA 17013 Sun. & Mon. Closed; Tuesday – Friday 10 AM – 5 PM; Saturday 10 AM – 2 PM G.B. Stuart History Workshop; 29 West High Street, Carlisle PA 17013 Thursday & Friday 10 AM-4 PM; Saturday 10 AM – 2 PM Cumberland Valley Visitors Center; 33 West High Street, Carlisle PA 17013 Sun. -

100 Trips in the Upper Midwest 101 Best Stories of Minnesota 125Th Anniversary

100 Trips in the Upper Midwest 101 Best Stories of Minnesota 125th Anniversary: Young America 150th Anniversary Celebraon 75 Years of Service Abstract and assessment book San Francisco 1904 AdJutant General's Annual Report, 1866 All Saints Lutheran Church: Norwood American Quilt, The Andrew Peterson and the Scandia Story Andrew Peterson Dairy, English translaon Army of Potomac Mr. Lincoln's Army Army of Potomac, The Glory Road Army of Potomac, the. A SDllness at Appomaox Atlas of Carver County 1954 Atlas of the North American Indian Banking in Minnesota Behind Barbed Wire Benton Township Minute Book, 2000-2006, 1986-1999 Benton Township Permit of Burial or Removal, 1910 Benton Township Property Owners, 1979 Benton Township Records 1945-1949 Benton Township Register of Birth and Death, 1941-1949 Benton Township Town Record Book, 1916-1921 Benton Township Treasurers Account Book, 1914-1923 Benton Township Treasurer's Account Book, 1934-1945, 1923-1933 Benton Township, Abstract of Assessment Roll, 1904 Benton Township, Account Book of Board of Supervisors, 1859-1897 Benton Township, Birth and Death index, 1926-1941 Benton Township, Book of Records, 1860-1905 Benton Township, Clerks Account Book and Court Records: 1990-2005 Benton Township, Clerks Account Book and Town Record 1955-1960, 1974-1976, 1977 -1981, 1982-1986 Benton Township, Clerks Account Book and Township Book 1950-1953, 1954-1961, 1910-1974, 1965-1970 Benton Township, Clerks Finance Record, 1960-1978 Benton Township, Clerk's Record of Receipts/Disbursements, 1939-1970 Benton -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) • United States Department of the Interior \ National Park Service National Register of Historic Places OCT23 Registration Form •RV This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations fc individual properties See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration For (National R< gister Bulletin 16A). CorE.pJ«J;$f$cK item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply •tbfl projwrty-being docume*rTf6a7*8~riler "N/A" for 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instruction. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name: Palace Amusements other names/site number: Palace Merry-Go-Round and Ferris Wheel Building 2. Location street and number: 201 -207 Lake Avenue N/A not for publication city or town: Asbury Park City N/A vicinity state: New Jersey county: Monmouth County zip code: 07712 3. State/Federal/Tribal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _j meets ... does not meet the National Register criteria. -

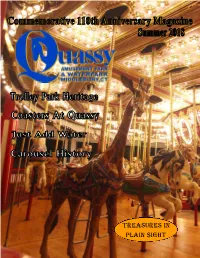

Treasures in Plain Sight

Treasures In Plain Sight 110th Anniversary Magazine Cover photo: The Grand Carousel at Quassy Amusement Park. The 50-foot ride arrived at the park in March of 1990 and is housed in one of the oldest structures on the property: a 1927 roundhouse. The current carousel replaced one that operated at Quassy for decades, which was auctioned in the fall of 1989. F e a t u r e S t o r i e s 3 Trolley Park Heritage Once owned an operated by an electrified rail line (trolley), Quassy is one of less than a dozen remaining trolley parks in the nation. Prior to the Great Depression of 1929, there were more than 1,000 such amusement parks. 6 The Coasters At Quassy Roller coasters are considered the cornerstone of many modern-day amusement parks. Quassy’s history with roller coasters dates back to 1952 when it introduced its first coaster. 12 Just Add Water Quassy entered the waterpark business in 2003 and hasn’t looked back since. Splash Away Bay has grown in leaps and bounds. 27 Treasures In Plain Sight Humpty Dumpty sat on a …. In this case a rooftop. Don’t overlook some of the treasures at Quassy Amusement Park that are right before your very eyes! Other Stories Inside... Carousels At Quassy Date Back To Early Years Billy’s Back In Town! He Went Full Circle Quassy’s Rides: A Mix Of The Old And New All Aboard The Refurbished Quassy Express All stories and photos in this publication are the property of Quassy Amusement Park Meet The Quassy Team and may not be reproduced without written permission.