Pragmatism's Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Kinds and Concepts: a Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account

Natural Kinds and Concepts: A Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account Ingo Brigandt Abstract: In this chapter I lay out a notion of philosophical naturalism that aligns with prag- matism. It is developed and illustrated by a presentation of my views on natural kinds and my theory of concepts. Both accounts reflect a methodological naturalism and are defended not by way of metaphysical considerations, but in terms of their philosophical fruitfulness. A core theme is that the epistemic interests of scientists have to be taken into account by any natural- istic philosophy of science in general, and any account of natural kinds and scientific concepts in particular. I conclude with general methodological remarks on how to develop and defend philosophical notions without using intuitions. The central aim of this essay is to put forward a notion of naturalism that broadly aligns with pragmatism. I do so by outlining my views on natural kinds and my account of concepts, which I have defended in recent publications (Brigandt, 2009, 2010b). Philosophical accounts of both natural kinds and con- cepts are usually taken to be metaphysical endeavours, which attempt to develop a theory of the nature of natural kinds (as objectively existing entities of the world) or of the nature of concepts (as objectively existing mental entities). However, I shall argue that any account of natural kinds or concepts must an- swer to epistemological questions as well and will offer a simultaneously prag- matist and naturalistic defence of my views on natural kinds and concepts. Many philosophers conceive of naturalism as a primarily metaphysical doc- trine, such as a commitment to a physicalist ontology or the idea that humans and their intellectual and moral capacities are a part of nature. -

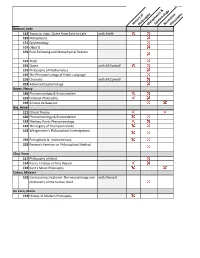

History of Philosophymetaphysics & Epistem Ology Norm Ative

HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Azzouni, Jody 114 Topics in Logic: Quine from Early to Late with Smith 120 Metaphysics 131 Epistemology 191 Objects 191 Rule-Following and Metaphysical Realism 191 Truth 191 Quine with McConnell 191 Philosophy of Mathematics 192 The Phenomenology of Public Language 195 Chomsky with McConnell 292 Advanced Epistemology Bauer, Nancy 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 191 Feminist Philosophy 192 Simone de Beauvoir Baz, Avner 121 Ethical Theory 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 192 Merleau Ponty Phenomenology 192 The Legacy of Thompson Clarke 192 Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations 292 Perceptions & Indeterminacy 292 Research Seminar on Philosophical Method Choi, Yoon 117 Philosophy of Mind 164 Kant's Critique of Pure Reason 192 Kant's Moral Philosophy Cohen, Michael 192 Conciousness Explored: The neurobiology and with Dennett philosophy of the human mind De Caro, Mario 152 History of Modern Philosophy De HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Car 191 Nature & Norms 191 Free Will & Moral Responsibility Denby, David 133 Philosophy of Language 152 History of Modern Philosophy 191 History of Analytic Philosophy 191 Topics in Metaphysics 195 The Philosophy of David Lewis Dennett, Dan 191 Foundations of Cognitive Science 192 Artificial Agents & Autonomy with Scheutz 192 Cultural Evolution-Is it Darwinian 192 Topics in Philosophy of Biology: The Boundaries with Forber of Darwinian Theory 192 Evolving Minds: From Bacteria to Bach 192 Conciousness -

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

03/05/2017 William James (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (ca. 1895, in The Letters of William James, ed. by Henry James, Boston, 1920) William James First published Thu Sep 7, 2000; substantive revision Tue Oct 29, 2013 William James was an original thinker in and between the disciplines of physiology, psychology and philosophy. His twelvehundred page masterwork, The Principles of Psychology (1890), is a rich blend of physiology, psychology, philosophy, and personal reflection that has given us such ideas as “the stream of thought” and the baby's impression of the world “as one great blooming, buzzing confusion” (PP 462). It contains seeds of pragmatism and phenomenology, and influenced generations of thinkers in Europe and America, including Edmund Husserl, Bertrand Russell, John Dewey, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. James studied at Harvard's Lawrence Scientific School and the School of Medicine, but his writings were from the outset as much philosophical as scientific. “Some Remarks on Spencer's Notion of Mind as Correspondence” (1878) and “The Sentiment of Rationality” (1879, 1882) presage his future pragmatism and pluralism, and contain the first statements of his view that philosophical theories are reflections of a philosopher's temperament. James hints at his religious concerns in his earliest essays and in The Principles, but they become more explicit in The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy (1897), Human Immortality: Two Supposed Objections to the Doctrine (1898), The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) and A Pluralistic Universe (1909). James oscillated between thinking that a “study in human nature” such as Varieties could contribute to a “Science of Religion” and the belief that religious experience involves an altogether supernatural domain, somehow inaccessible to science but accessible to the individual human subject. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

The Generalization of Logic According to G.Boole, A.De Morgan

South American Journal of Logic Vol. 3, n. 2, pp. 415{481, 2017 ISSN: 2446-6719 Squaring the unknown: The generalization of logic according to G. Boole, A. De Morgan, and C. S. Peirce Cassiano Terra Rodrigues Abstract This article shows the development of symbolic mathematical logic in the works of G. Boole, A. De Morgan, and C. S. Peirce. Starting from limitations found in syllogistic, Boole devised a calculus for what he called the algebra of logic. Modifying the interpretation of categorial proposi- tions to make them agree with algebraic equations, Boole was able to show an isomorphism between the calculus of classes and of propositions, being indeed the first to mathematize logic. Having a different purport than Boole's system, De Morgan's is conceived as an improvement on syllogistic and as an instrument for the study of it. With a very unusual system of symbols of his own, De Morgan develops the study of logical relations that are defined by the very operation of signs. Although his logic is not a Boolean algebra of logic, Boole took from De Morgan at least one central notion, namely, the one of a universe of discourse. Peirce crit- ically sets out both from Boole and from De Morgan. Firstly, claiming Boole had exaggeratedly submitted logic to mathematics, Peirce strives to distinguish the nature and the purpose of each discipline. Secondly, identifying De Morgan's limitations in his rigid restraint of logic to the study of relations, Peirce develops compositions of relations with classes. From such criticisms, Peirce not only devises a multiple quantification theory, but also construes a very original and strong conception of logic as a normative science. -

Peirce for Whitehead Handbook

For M. Weber (ed.): Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought Ontos Verlag, Frankfurt, 2008, vol. 2, 481-487 Charles S. Peirce (1839-1914) By Jaime Nubiola1 1. Brief Vita Charles Sanders Peirce [pronounced "purse"], was born on 10 September 1839 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Sarah and Benjamin Peirce. His family was already academically distinguished, his father being a professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard. Though Charles himself received a graduate degree in chemistry from Harvard University, he never succeeded in obtaining a tenured academic position. Peirce's academic ambitions were frustrated in part by his difficult —perhaps manic-depressive— personality, combined with the scandal surrounding his second marriage, which he contracted soon after his divorce from Harriet Melusina Fay. He undertook a career as a scientist for the United States Coast Survey (1859- 1891), working especially in geodesy and in pendulum determinations. From 1879 through 1884, he was a part-time lecturer in Logic at Johns Hopkins University. In 1887, Peirce moved with his second wife, Juliette Froissy, to Milford, Pennsylvania, where in 1914, after 26 years of prolific and intense writing, he died of cancer. He had no children. Peirce published two books, Photometric Researches (1878) and Studies in Logic (1883), and a large number of papers in journals in widely differing areas. His manuscripts, a great many of which remain unpublished, run to some 100,000 pages. In 1931-58, a selection of his writings was arranged thematically and published in eight volumes as the Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Beginning in 1982, a number of volumes have been published in the series A Chronological Edition, which will ultimately consist of thirty volumes. -

The Hiring of James Mark Baldwin and James Gibson Hume at Toronto in 1889

History of Psychology Copyright 2004 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2004, Vol. 7, No. 2, 130–153 1093-4510/04/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/1093-4510.7.2.130 THE HIRING OF JAMES MARK BALDWIN AND JAMES GIBSON HUME AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO IN 1889 Christopher D. Green York University In 1889, George Paxton Young, the University of Toronto’s philosophy professor, passed away suddenly while in the midst of a public debate over the merits of hiring Canadians in preference to American and British applicants for faculty positions. As a result, the process of replacing Young turned into a continuation of that argument, becoming quite vociferous and involving the popular press and the Ontario gov- ernment. This article examines the intellectual, political, and personal dynamics at work in the battle over Young’s replacement and its eventual resolution. The outcome would have an impact on both the Canadian intellectual scene and the development of experimental psychology in North America. In 1889 the University of Toronto was looking to hire a new professor of philosophy. The normally straightforward process of making a university appoint- ment, however, rapidly descended into an unseemly public battle involving not just university administrators, but also the highest levels of the Ontario govern- ment, the popular press, and the population of the city at large. The debate was not pitched solely, or even primarily, at the level of intellectual issues, but became intertwined with contentious popular questions of nationalism, religion, and the proper place of science in public education. The impact of the choice ultimately made would reverberate not only through the university and through Canada’s broader educational establishment for decades to come but, because it involved James Mark Baldwin—a man in the process of becoming one of the most prominent figures in the study of the mind—it also rippled through the nascent discipline of experimental psychology, just then gathering steam in the United States of America. -

Peirce and the Founding of American Sociology

Journal of Classical Sociology Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi Vol 6(1): 23–50 DOI: 10.1177/1468795X06061283 www.sagepublications.com Peirce and the Founding of American Sociology NORBERT WILEY University of Illinois, Urbana ABSTRACT This paper argues that Charles Sanders Peirce contributed signific- antly to the founding of American sociology, doing so at the level of philosophical presuppositions or meta-sociology. I emphasize two of his ideas. One is semiotics, which is virtually the same as the anthropologists’ concept of culture. This latter concept in turn was essential to clarifying the sociologists’ idea of the social or society. Peirce also created the modern theory of the dialogical self, which explained the symbolic character of human beings and proved foundational for social psychology. Politically Peirce was a right-wing conservative, but his ideas eventually contributed to the egalitarian views of culures and sub-cultures. In addition his ideas contributed, by way of unanticipated consequences, to the 20th- century human rights revolutions in the American legal system. Thus he was both a founder of sociology and a founder of American political liberalism. KEYWORDS early American sociology, inner speech, Peirce, semiotics Introduction Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) originated several ideas that contributed to social theory, particularly to its philosophical underpinnings. Some of these are in unfamiliar contexts and in need of a slight re-framing or re-conceptualization. They also need to be related to each other. But, assuming these finishing touches, Peirce hadFirst a cluster of powerful insights that tradeProof heavily on the notions of the symbolic, the semiotic, the dialogical, the cultural and the self – ideas central to social theory. -

An Examination of Introductory Psychology Textbooks in America Randall D

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Articles Faculty Publications 1992 Portraits of a Discipline: An Examination of Introductory Psychology Textbooks in America Randall D. Wight Ouachita Baptist University, [email protected] Wayne Weiten Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/articles Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Weiten, W. & Wight, R. D. (1992). Portraits of a discipline: An examination of introductory psychology textbooks in America. In C. L. Brewer, A. Puente, & J. R. Matthews (Eds.), Teaching of psychology in America: A history (pp. 453-504). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 20 PORTRAITS OF A DISCIPLINE: AN EXAMINATION OF INTRODUCTORY PSYCHOLOGY TEXTBOOKS IN AMERICA WAYNE WEITEN AND RANDALL D. WIGHT The time has gone by when any one person could hope to write an adequate textbook of psychology. The science has now so many branches, so many methods, so many fields of application, and such an immense mass of data of observation is now on record, that no one person can hope to have the necessary familiarity with the whole. -An author of an introductory psychology text If we compare general psychology textbooks of today with those of from ten to twenty years ago we note an undeniable trend toward amelio- We are indebted to several people who provided helpful information in responding to our survey discussed in the second half of the chapter, including Solomon Diamond for calling attention to Samuel Johnson and Noah Porter, Ernest R. -

George Trumbull Ladd (1842-1921)

The International Journal of Indian Psychology ISSN 2348-5396 (e) | ISSN: 2349-3429 (p) Volume 6, Issue 4, DIP 18.01.001/20180604 DOI: 10.25215/0604.001 http://www.ijip.in | October - December, 2018 TimeLine Person of the Month: George Trumbull Ladd (1842-1921) Ankit Patel1* Born January 19, 1842 Painesville, Lake County, Ohio, US Died August 8, 1921 (aged 79) New Haven, Connecticut, US Citizenship American Known for The Principles of Church Polity (1882), What is the Bible? (1888), Philosophy of Knowledge (1897) Education Western Reserve College Andover Theological Seminary George Trumbull Ladd, (born January 19, 1842, Painesville, Ohio, U.S.—died August 8, 1921, New Haven, Connecticut), philosopher and psychologist whose textbooks were influential in establishing experimental psychology in the United States. He called for a scientific psychology, but he viewed psychology as ancillary to philosophy. He was a grandson of Jesse Ladd and Ruby Brewster, who were among the original pioneers in Madison, Lake County, Ohio. Ruby was a granddaughter of Oliver Brewster and Martha Wadsworth Brewster, a poet and writer, and one of the earliest American female literary figures. Ladd’s main interest was in writing Elements of Physiological Psychology (1887), the first handbook of its kind in English. Because of its emphasis on neurophysiology, it long remained a standard work. In addition, Ladd’s Psychology, Descriptive and Explanatory (1894) is important as a theoretical system of functional psychology, considering the human being as an organism with a mind purposefully solving problems and adapting to its environment. He early gave indications of the studious habits that characterized him through life. -

The Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85128-2 - The Cambridge Companion to the Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L. Hull and Michael Ruse Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to THE PHILOSOPHY OF BIOLOGY The philosophy of biology is one of the most exciting new areas in the field of philosophy and one that is attracting much attention from working scientists. This Companion, edited by two of the founders of the field, includes newly commissioned essays by senior scholars and by up-and- coming younger scholars who collectively examine the main areas of the subject – the nature of evolutionary theory, classification, teleology and function, ecology, and the prob- lematic relationship between biology and religion, among other topics. Up-to-date and comprehensive in its coverage, this unique volume will be of interest not only to professional philosophers but also to students in the humanities and researchers in the life sciences and related areas of inquiry. David L. Hull is an emeritus professor of philosophy at Northwestern University. The author of numerous books and articles on topics in systematics, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology, and naturalized epistemology, he is a recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Michael Ruse is professor of philosophy at Florida State University. He is the author of many books on evolutionary biology, including Can a Darwinian Be a Christian? and Darwinism and Its Discontents, both published by Cam- bridge University Press. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he has appeared on television and radio, and he contributes regularly to popular media such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Playboy magazine. -

May 03 CI.Qxd

Philosophy of Chemistry by Eric Scerri Of course, the field of compu- hen I push my hand down onto my desk it tational quantum chemistry, does not generally pass through the which Dirac and other pioneers Wwooden surface. Why not? From the per- of quantum mechanics inadver- spective of physics perhaps it ought to, since we are tently started, has been increas- told that the atoms that make up all materials consist ingly fruitful in modern mostly of empty space. Here is a similar question that chemistry. But this activity has is put in a more sophisticated fashion. In modern certainly not replaced the kind of physics any body is described as a superposition of chemistry in which most practitioners are engaged. many wavefunctions, all of which stretch out to infin- Indeed, chemists far outnumber scientists in all other ity in principle. How is it then that the person I am fields of science. According to some indicators, such as talking to across my desk appears to be located in one the numbers of articles published per year, chemistry particular place? may even outnumber all the other fields of science put together. If there is any sense in which chemistry can The general answer to both such questions is that be said to have been reduced then it can equally be although the physics of microscopic objects essen- said to be in a high state of "oxidation" regarding cur- tially governs all of matter, one must also appeal to rent academic and industrial productivity. the laws of chemistry, material science, biology, and Starting in the early 1990s a group of philosophers other sciences.