New England Indians and Colonizing Pigs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![About Pigs [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0911/about-pigs-pdf-50911.webp)

About Pigs [PDF]

May 2015 About Pigs Pigs are highly intelligent, social animals, displaying elaborate maternal, communicative, and affiliative behavior. Wild and feral pigs inhabit wide tracts of the southern and mid-western United States, where they thrive in a variety of habitats. They form matriarchal social groups, sleep in communal nests, and maintain close family bonds into adulthood. Science has helped shed light on the depths of the remarkable cognitive abilities of pigs, and fosters a greater appreciation for these often maligned and misunderstood animals. Background Pigs—also called swine or hogs—belong to the Suidae family1 and along with cattle, sheep, goats, camels, deer, giraffes, and hippopotamuses, are part of the order Artiodactyla, or even-toed ungulates.2 Domesticated pigs are descendants of the wild boar (Sus scrofa),3,4 which originally ranged through North Africa, Asia and Europe.5 Pigs were first domesticated approximately 9,000 years ago.6 The wild boar became extinct in Britain in the 17th century as a result of hunting and habitat destruction, but they have since been reintroduced.7,8 Feral pigs (domesticated animals who have returned to a wild state) are now found worldwide in temperate and tropical regions such as Australia, New Zealand, and Indonesia and on island nations, 9 such as Hawaii.10 True wild pigs are not native to the New World.11 When Christopher Columbus landed in Cuba in 1493, he brought the first domestic pigs—pigs who subsequently spread throughout the Spanish West Indies (Caribbean).12 In 1539, Spanish explorers brought pigs to the mainland when they settled in Florida. -

Rev. John White, the Founder of New England Launching the Journey Towards Unitarianism

Rev. John White, The Founder of New England Launching the Journey Towards Unitarianism The founder of New England never saw its shores. John White was his name. He was the rector of St. Peters and Holy Trinity Parishes in Dorchester, the small county town of Devon in the West of England. He set into motion the movement that culminated in the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. There had been several visitors to the coast for nearly a century before White began his endeavors, Champlain, Cabot, Smith, and Gosnold among them. Temporary trading posts were established with the goal of exploiting such resources as furs and fish. But there was no vision of establishing permanent settlements in the region. While a group of Separatists had landed on Cape Cod Bay in 1620, they had set out from Leiden after years of self-imposed exile in The Netherlands. They did pause briefly in Plymouth in Devon; they had little connection with any larger organized group in England. They survived in Plymouth in Massachusetts. Captain John Smith, after his initial efforts in Jamestown, became an advocate for more permanent settlements. But, unlike the so-called Pilgrims, those that were planted were not based on religious convictions. Samuel Eliot Morrison in his Builders of the Bay Colony mentions several. “Massachusetts (named by Captain John Smith) was dotted with petty fishing and trading stations. There was William Blaxton, who set up bachelor quarters on the eminence later known as Beacon Hill, Thomas Watford, the pioneer of Charlestown; Samuel Maverick at Winnesimmit (now Chelsea), David Thompson, a Scots gentleman, who settled the island in Boston harbor that still bears his name…” (Morrison, p. -

William Blaxton

1 “THIS MAN, INDEED, WAS OF A PARTICULAR HUMOR.” The family names Blackstone, Blackston, Blackiston, Blakeston, Blakiston, Blaxton according to P.H. Reaney’s A DICTIONARY OF BRITISH SURNAMES: • Blackstan is the first entry in 1086 in the doomsday book for Essex. William Blacston, Blakeston, Blackstan 1235-42 entered in the Fees (LIBER FEODORUM, 3 volumes, London, 1920-1931) for Buckinghamshire. Old English Laecstan meaning “black stone.” • Philip Atteblakeston 1275 entered in the Subsidary Rolls for Worcestershire (Worcestershire History Society, 4 volumes, 1893-1900); William de Blakstan 1316 Feet of Fines for Kent (ARCHAEOLOGIA CANTIANA 11-15, 18, 20, 1877-93; Kent Records Society 15, 1956). Means “dweller by the black stone,” as at Blackstone Edge (Lancashire) or Blaxton (West Riding of Yorkshire). “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Per the Reverend Cotton Mather. HDT WHAT? INDEX WILLIAM BLACKSTONE REVEREND WILLIAM BLAXTON 1596 March 5, Friday (1595, Old Style): William Blaxton was born. He would be educated at Emanuel in Cambridge, which was often referred to as “the Puritan college,” taking his degree in 1617, after which probably he would have been ordained. NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT William Blackstone “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX REVEREND WILLIAM BLAXTON WILLIAM BLACKSTONE 1622 Captain John Mason and Sir Ferdinando Gorges, a couple of guys who knew how to work the system, received a patent from the Plymouth Council for New England for all the territory lying between the Merrimack River and the Kennebec River, which territory was to be known as the Province of Maine. -

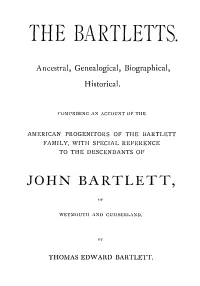

1~He Bartletts

1~HE BARTLETTS. Ancestral, Genealogical, Biographical, His tori ca 1. CO~ll'RISING ,\:'I ,\CCOUNT Or THE AMERICAN PROGENITORS OF THE BARTLETT FAMILY, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE DESCENDANTS OF JOHN BARTLETT, ()J,' WEY~IOUTll AND CU~IIIERl.i\ND. II\' THOMAS EDW AH.D BAHTLETT. Sl!W 11.\\'l!S, CONN,: l'llF.!.S Of' TIii! ~"l',\l'lt111:t1 l'IUNTING co .• St'.i-9u CIWWN !;'l'IUrnT. " Happy who, with bright regard looks back Upon his father's fathers ; who with joy Recounts their deeds of grace, and in himself Values the latest link in the f.tir chain Of noble sequences; for nature loves Not at one bound to achieve her topmost tyj,c, But step by step she leads a family on· To demigod or devil ; the rare joy Or horror of the world." MEMORIAL. THIS work, the imperfect result of much loving labor, was inspired by grateful remembrance of the tender, patient, noble-minded Eber Bartlett, father of the Author and Com piler. It is very likely, an unimportant tribute to a man whose unselfish life was very rich in benefit to his children and all others, even of alien households, but there is a com - fort of a peculiar kind, founded upon most grateful recollec tions of one of the kindest of parents, in thus dedicating to him the result of very many days pleasantly and perhaps not quite unprofitably, occupied. With reverential affection has the writer ever borne in mind the gentle, courageous, forbearing ancestor, whose virtues are herein altogether too indifferently commemorated. -

Pig Husbandry in Iron Age Israel and Judah

Pig Husbandry in Iron Age Israel and Judah: New Insights Regarding the Origin of the "Taboo" Author(s): Lidar Sapir-Hen, Guy Bar-Oz, Yuval Gadot and Israel Finkelstein Source: Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (1953-), Bd. 129, H. 1 (2013), pp. 1-20 Published by: Deutscher verein zur Erforschung Palästinas Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43664894 Accessed: 03-10-2018 18:50 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Deutscher verein zur Erforschung Palästinas is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (1953-) This content downloaded from 129.2.19.102 on Wed, 03 Oct 2018 18:50:48 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Pig Husbandry in Iron Age Israel and Judah New Insights Regarding the Origin of the "Taboo" By Lidar Sapir-Hen, Guy Bar-Oz, Yuval Gadot, and Israel Finkelstein 1. Introduction The biblical prohibition against the consumption of pork (Lev 11:7; Deut 14:8), observed in Judaism for over two millennia, is the reason for the special attention paid to the appearance of pig bones in Iron Age strata in the southern Levant1. -

Boston a Guide Book to the City and Vicinity

1928 Tufts College Library GIFT OF ALUMNI BOSTON A GUIDE BOOK TO THE CITY AND VICINITY BY EDWIN M. BACON REVISED BY LeROY PHILLIPS GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO • LONDON ATLANTA • DALLAS • COLUMBUS • SAN FRANCISCO COPYRIGHT, 1928, BY GINN AND COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 328.1 (Cfte gtftengum ^regg GINN AND COMPANY • PRO- PRIETORS . BOSTON • U.S.A. CONTENTS PAGE PAGE Introductory vii Brookline, Newton, and The Way about Town ... vii Wellesley 122 Watertown and Waltham . "123 1. Modern Boston i Milton, the Blue Hills, Historical Sketch i Quincy, and Dedham . 124 Boston Proper 2 Winthrop and Revere . 127 1. The Central District . 4 Chelsea and Everett ... 127 2. The North End .... 57 Somerville, Medford, and 3. The Charlestown District 68 Winchester 128 4. The West End 71 5. The Back Bay District . 78 III. Public Parks 130 6. The Park Square District Metropolitan System . 130 and the South End . loi Boston City System ... 132 7. The Outlying Districts . 103 IV. Day Trips from Boston . 134 East Boston 103 Lexington and Concord . 134 South Boston .... 103 Boston Harbor and Massa- Roxbury District ... 105 chusetts Bay 139 West Roxbury District 105 The North Shore 141 Dorchester District . 107 The South Shore 143 Brighton District. 107 Park District . Hyde 107 Motor Sight-Seeing Trips . 146 n. The Metropolitan Region 108 Important Points of Interest 147 Cambridge and Harvard . 108 Index 153 MAPS PAGE PAGE Back Bay District, Showing Copley Square and Vicinity . 86 Connections with Down-Town Cambridge in the Vicinity of Boston vii Harvard University ... -

Early Starrs in Kent &New England

**************************** Early Starrs in Kent &New England **************************** by HOSEA STARR BALLOU * Honorary Governor of THE SOCIETY OF COLONIAL WARS IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS President Emeritus of THE STARR FAMILY ASSOCIATION Member of THE BUNKER HILL MONUMENT ASSOCIATION THE UNIVERSALIST HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE NEW ENGLAND HISTORIC GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY **************************** BOSTON STARR FAMILY ASSOCIATION 1944 Arranged and Edited by WILLIAM CARROLL HILL Editor and Historian The New England Historic Genealogical Society 9 Ashburton Place, Boston, Mass. THE RUMFORD PRESS CONCORD, NEW HAMPSHIRE PRINTED IN THE U. S. A. PREFACE "Early Starrs in Kent and New England" is the compilation of a series of articles on the forbears of the Starr family in this country and England prepared for and published in The New England His torical and Genealogical Register between the years 1935 and 1944. They were prepared by Hosea Starr Ballou of Brookline, Mass., who had spent many years in this country and abroad in genealogical research. Having previously published the "Life of Hosea Ballou II," "Wm. Blaxton, The First Bostonian" and "The Harvard Yard Before Dunster", Mr. Ballou spent much of the last decade of his life in a study and analysis of the data on the Starr Family. Not having in mind a formal history of the family, Mr. Ballou contributed frequently to The Register of such material as he had at hand at the time, with the result that the articles, while containing a wonderful amount of new and most valuable information, pre sented no chronological sequence, being classified in general as "Dr. Thomas Starr in the Pequot War", although the text embraced far more than this narrative. -

The Food Industry Scorecard

THE FOOD INDUSTRY SCORECARD An evaluation of food companies’ progress making—and keeping— animal welfare promises humanesociety.org/scorecard Executive summary Most of the largest U.S. food companies have publicly pledged to eliminate certain animal abuses from their supply chains. But as countless consumers have asked: are they keeping their promises? For context, the vast majority of animals in our food system live Here’s the good news: that kind of radical view is out of in dismal conditions. Mother pigs are locked in gestation crates step with traditional American values. Agribusiness may see ani- so small they can’t turn around. Egg-laying hens are crammed mals as mere machines, but consumers don’t. into cages so tightly they can’t even spread their wings. And chickens in the poultry industry are bred to grow so large, so ɠ As the American Farm Bureau reports, nearly all consumers (95%) believe farm animals should be fast they suffer from agonizing leg disorders. treated well. It wasn’t always this way. Throughout history, animals hav- en’t been forced to endure such miserable lives. (And today, ɠ The Food Marketing Institute found that animal welfare is shoppers’ second most important social issue. there are certainly farmers who don’t use these abusive prac- tices.) But as agri-culture developed into agri-business, the ɠ The food industry analytics firm Technomic concluded industry’s relationship to animals became more severe. that for American restaurant patrons, concerns about animal cruelty outweigh those regarding the “Forget the pig is an animal,” urged Hog Farm Management environment, fair trade, local sourcing and other issues. -

Fall 2021 Kids OMNIBUS

FALL 2021 RAINCOAST OMNIBUS Kids This edition of the catalogue was printed on May 13, 2021. To view updates, please see the Fall 2021 Raincoast eCatalogue or visit www.raincoast.com Raincoast Books Fall 2021 - Kids Omnibus Page 1 of 266 A Cub Story by Alison Farrell and Kristen Tracy Timeless and nostalgic, quirky and fresh, lightly educational and wholly heartfelt, this autobiography of a bear cub will delight all cuddlers and snugglers. See the world through a bear cub's eyes in this charming book about finding your place in the world. Little cub measures himself up to the other animals in the forest. Compared to a rabbit, he is big. Compared to a chipmunk, he is HUGE. Compared to his mother, he is still a little cub. The first in a series of board books pairs Kristen Tracy's timeless and nostalgic text with Alison Farrell's sweet, endearing art for an adorable treatment of everyone's favorite topic, baby animals. Author Bio Chronicle Books Alison Farrell has a deep and abiding love for wild berries and other foraged On Sale: Sep 28/21 foods. She lives, bikes, and hikes in Portland, Oregon, and other places in the 6 x 9 • 22 pages Pacific Northwest. full-color illustrations throughout 9781452174587 • $14.99 Kristen Tracy writes books for teens and tweens and people younger than Juvenile Fiction / Animals / Baby Animals • Ages 2-4 that, and also writes poetry for adults. She's spent a lot of her life teaching years writing at places like Johnson State College, Western Michigan University, Brigham Young University, 826 Valencia, and Stanford University. -

Evaluation of Crates and Girth Tethers for Sows: Reproductive Performance, Immunity, Behavior and Ergonomic Measures

APPLIED ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR SCIENCE E LS EV I ER Applied Animal Behaviour Science 39 (1994) 297-311 Evaluation of crates and girth tethers for sows: reproductive performance, immunity, behavior and ergonomic measures John J. McGlone*, Janeen L. Salak-Johnson, Rhonda I. Nicholson, Tiffanie Hicks Pork Industry Institute, Department of Animal Science and Food Technology Department, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-2141, USA (Accepted 31 October 1993 ) Abstract An evaluation of reproductive performance, behavior, immunity and ergonomics was conducted for two common sow housing systems: the girth tether and crate. Littermate Yorkshire × Landrace gilts were randomly assigned to either the crate or girth tether sys- tem and they remained in that treatment for two consecutive pregnancies and lactations. A total of 171 matings resulted in 141 litters (82.4% farrowing rate). Second parity sows penned in girth tethers had 1.5 fewer piglets born and 1.3 fewer piglets weaned than sows in the crate system (P< 0.05 ). Owing to smaller litter sizes, piglets of nursing sows in the girth tether system were heavier (P<0.01) at weaning. Immune measures showed no treatment effects. Behavioral measures indicated crated gilts and sows were more active overall (P< 0.01 ) than girth tethered sows. In addition, sows in the gestation crate showed more (P< 0.05 ) oral/nasal stereotypies, sitting and drinking than sows in the girth tether system. Less time was required to catch litters of piglets (P< 0.05 ) in the girth tether than in the crate farrowing environment. We concluded that the girth tether system we evalu- ated was undesirable from a welfare and economic standpoint, and use should be discour- aged on commercial farms. -

Robert Fuller

RE:CORDS OF ROBERT FLJLLER RECORDS OF ROBERT FULLER of Salem and Rehoboth AND SOME OF HIS DESCENDANTS by Clarence C. Fuller Foxboro, Mass. Privately Printed in Norwood, Mass. Printed in the United States of America by NORWOOD PRINTING COMPANY, Norwood, Mass. 1969 THE GOOD SHEPHERD Memorial window at the First Baptist Church, Mansfield, Mass. ''In memory of Deacon Pierpont M. Edwards and Susan Fuller Edwards'' Dedicated J u1y 1914 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Historical Sketches . 1 Early History of Salem . 1 Early History of Rehoboth . 3 II. Roberti Fuller, ca. 1615 - 1706 . 17 Original Rehobo~h Land Records concerning Roberti Fuller . 48 Recorded Deeds of Robertl Fuller . 60 Recorded Deeds of Robert and Margaret Fuller . 66 The Bowen Family of Early Rehoboth . 73 III. Samuel2 Fuller, ca. l 649 - 1724 . 77 Samuel's Estate . 81 Ide Family of Early Rehoboth . 86 IV. Samue13 Fuller, 1676 - 1724 . 87 Estate of Samuel3 Fuller . 96 Land Owned by Samuel3 Fuller .... _. 108 Wilmarth Family of Early Rehoboth . 117 V. Timothy4 Fuller, 1710/11 - 1782 ................ 121 Timothy's Estate . 144 Land Transactions of Timothy4 Fuller ........... 159 Recorded Deeds of Timothy4 Fuller . 165 Hannah Bliss and Her Father's Estate ............ 172 Bliss Family of Early Rehoboth ................ 176 Notes on the Thurber Family Genealogy . 180 VI. Timothy5 Fuller, 175 l - 1809 .................. 184 Estate of His Mother, Elizabeth (Thurber) Fuller ... 191 Settlement of Timothy's Estate . 196 Land Transactions of Timothy5 Fuller . 21 O Notes on the Medbury Family ................. 220 V vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Vil. Timothy6 Fuller, 1799 - 1866 .................. 222 Timothy's Estate .......................... -

The Ethical Implications of Genetically Modified Pigs

THE ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS OF GENETICALLY MODIFIED PIGS by Brittany Peet Food & Drug Law Professor Neal Fortin December 5, 2007 Brittany Peet The Ethical Implications of Genetically Modified Pigs 2 THE ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS OF GENETICALLY MODIFIED PIGS TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………….1 I. What is a Genetically Improved Pig?...................................................................1 II. How it All Began……………………………………………………………….3 A. The Life Cycle of Pigs/Pork……………………………………………3 B. Overview of the Law…………………………………………………...4 1. Federal Statutes…………………………………………………4 2. State Statutes……………………………………………………5 C. The Corporate Farm……………………………………………………6 1. Vertical Integration……………………………………………..6 2. The Disastrous Genetics of Leaner Varieties of Hog…………..9 III. The Life of the Genetically Modified Pig……………………………………10 A. AI……………………………………………………………………..10 B. Disease Vulnerability…………………………………………………11 C. Living Quarters……………………………………………………….12 D. Treatment Affects Taste: Acidity……………………………………..13 IV. Suggestions for Change……………………………………………………...14 A. Consumer Demand and Niche Pork…………………………………..15 B. The European Model………………………………………………….17 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………….18 Brittany Peet The Ethical Implications of Genetically Modified Pigs 3 Introduction The industrialization of farming has caused extreme distress in pigs raised for food. This paper will outline current statutory protections in place for livestock welfare, conditions pigs face on modern factory farms, and how these conditions and genetic selection lead to lower quality pork. This paper will conclude by contending that the United States is beginning to move in the direction of ethically produced meat, and that this trend can continue by educating consumers and encouraging movements like the niche pork movement. Finally, the paper will recommend that the United States follow the lead of the European Union by passing federal criminal statutes that protect the welfare of animals on farms.