Rev. John White, the Founder of New England Launching the Journey Towards Unitarianism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Blaxton

1 “THIS MAN, INDEED, WAS OF A PARTICULAR HUMOR.” The family names Blackstone, Blackston, Blackiston, Blakeston, Blakiston, Blaxton according to P.H. Reaney’s A DICTIONARY OF BRITISH SURNAMES: • Blackstan is the first entry in 1086 in the doomsday book for Essex. William Blacston, Blakeston, Blackstan 1235-42 entered in the Fees (LIBER FEODORUM, 3 volumes, London, 1920-1931) for Buckinghamshire. Old English Laecstan meaning “black stone.” • Philip Atteblakeston 1275 entered in the Subsidary Rolls for Worcestershire (Worcestershire History Society, 4 volumes, 1893-1900); William de Blakstan 1316 Feet of Fines for Kent (ARCHAEOLOGIA CANTIANA 11-15, 18, 20, 1877-93; Kent Records Society 15, 1956). Means “dweller by the black stone,” as at Blackstone Edge (Lancashire) or Blaxton (West Riding of Yorkshire). “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Per the Reverend Cotton Mather. HDT WHAT? INDEX WILLIAM BLACKSTONE REVEREND WILLIAM BLAXTON 1596 March 5, Friday (1595, Old Style): William Blaxton was born. He would be educated at Emanuel in Cambridge, which was often referred to as “the Puritan college,” taking his degree in 1617, after which probably he would have been ordained. NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT William Blackstone “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX REVEREND WILLIAM BLAXTON WILLIAM BLACKSTONE 1622 Captain John Mason and Sir Ferdinando Gorges, a couple of guys who knew how to work the system, received a patent from the Plymouth Council for New England for all the territory lying between the Merrimack River and the Kennebec River, which territory was to be known as the Province of Maine. -

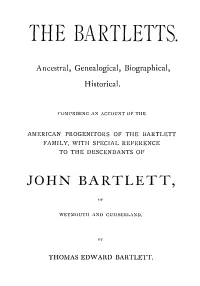

1~He Bartletts

1~HE BARTLETTS. Ancestral, Genealogical, Biographical, His tori ca 1. CO~ll'RISING ,\:'I ,\CCOUNT Or THE AMERICAN PROGENITORS OF THE BARTLETT FAMILY, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE DESCENDANTS OF JOHN BARTLETT, ()J,' WEY~IOUTll AND CU~IIIERl.i\ND. II\' THOMAS EDW AH.D BAHTLETT. Sl!W 11.\\'l!S, CONN,: l'llF.!.S Of' TIii! ~"l',\l'lt111:t1 l'IUNTING co .• St'.i-9u CIWWN !;'l'IUrnT. " Happy who, with bright regard looks back Upon his father's fathers ; who with joy Recounts their deeds of grace, and in himself Values the latest link in the f.tir chain Of noble sequences; for nature loves Not at one bound to achieve her topmost tyj,c, But step by step she leads a family on· To demigod or devil ; the rare joy Or horror of the world." MEMORIAL. THIS work, the imperfect result of much loving labor, was inspired by grateful remembrance of the tender, patient, noble-minded Eber Bartlett, father of the Author and Com piler. It is very likely, an unimportant tribute to a man whose unselfish life was very rich in benefit to his children and all others, even of alien households, but there is a com - fort of a peculiar kind, founded upon most grateful recollec tions of one of the kindest of parents, in thus dedicating to him the result of very many days pleasantly and perhaps not quite unprofitably, occupied. With reverential affection has the writer ever borne in mind the gentle, courageous, forbearing ancestor, whose virtues are herein altogether too indifferently commemorated. -

Boston a Guide Book to the City and Vicinity

1928 Tufts College Library GIFT OF ALUMNI BOSTON A GUIDE BOOK TO THE CITY AND VICINITY BY EDWIN M. BACON REVISED BY LeROY PHILLIPS GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO • LONDON ATLANTA • DALLAS • COLUMBUS • SAN FRANCISCO COPYRIGHT, 1928, BY GINN AND COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 328.1 (Cfte gtftengum ^regg GINN AND COMPANY • PRO- PRIETORS . BOSTON • U.S.A. CONTENTS PAGE PAGE Introductory vii Brookline, Newton, and The Way about Town ... vii Wellesley 122 Watertown and Waltham . "123 1. Modern Boston i Milton, the Blue Hills, Historical Sketch i Quincy, and Dedham . 124 Boston Proper 2 Winthrop and Revere . 127 1. The Central District . 4 Chelsea and Everett ... 127 2. The North End .... 57 Somerville, Medford, and 3. The Charlestown District 68 Winchester 128 4. The West End 71 5. The Back Bay District . 78 III. Public Parks 130 6. The Park Square District Metropolitan System . 130 and the South End . loi Boston City System ... 132 7. The Outlying Districts . 103 IV. Day Trips from Boston . 134 East Boston 103 Lexington and Concord . 134 South Boston .... 103 Boston Harbor and Massa- Roxbury District ... 105 chusetts Bay 139 West Roxbury District 105 The North Shore 141 Dorchester District . 107 The South Shore 143 Brighton District. 107 Park District . Hyde 107 Motor Sight-Seeing Trips . 146 n. The Metropolitan Region 108 Important Points of Interest 147 Cambridge and Harvard . 108 Index 153 MAPS PAGE PAGE Back Bay District, Showing Copley Square and Vicinity . 86 Connections with Down-Town Cambridge in the Vicinity of Boston vii Harvard University ... -

Early Starrs in Kent &New England

**************************** Early Starrs in Kent &New England **************************** by HOSEA STARR BALLOU * Honorary Governor of THE SOCIETY OF COLONIAL WARS IN THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS President Emeritus of THE STARR FAMILY ASSOCIATION Member of THE BUNKER HILL MONUMENT ASSOCIATION THE UNIVERSALIST HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE NEW ENGLAND HISTORIC GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY **************************** BOSTON STARR FAMILY ASSOCIATION 1944 Arranged and Edited by WILLIAM CARROLL HILL Editor and Historian The New England Historic Genealogical Society 9 Ashburton Place, Boston, Mass. THE RUMFORD PRESS CONCORD, NEW HAMPSHIRE PRINTED IN THE U. S. A. PREFACE "Early Starrs in Kent and New England" is the compilation of a series of articles on the forbears of the Starr family in this country and England prepared for and published in The New England His torical and Genealogical Register between the years 1935 and 1944. They were prepared by Hosea Starr Ballou of Brookline, Mass., who had spent many years in this country and abroad in genealogical research. Having previously published the "Life of Hosea Ballou II," "Wm. Blaxton, The First Bostonian" and "The Harvard Yard Before Dunster", Mr. Ballou spent much of the last decade of his life in a study and analysis of the data on the Starr Family. Not having in mind a formal history of the family, Mr. Ballou contributed frequently to The Register of such material as he had at hand at the time, with the result that the articles, while containing a wonderful amount of new and most valuable information, pre sented no chronological sequence, being classified in general as "Dr. Thomas Starr in the Pequot War", although the text embraced far more than this narrative. -

Robert Fuller

RE:CORDS OF ROBERT FLJLLER RECORDS OF ROBERT FULLER of Salem and Rehoboth AND SOME OF HIS DESCENDANTS by Clarence C. Fuller Foxboro, Mass. Privately Printed in Norwood, Mass. Printed in the United States of America by NORWOOD PRINTING COMPANY, Norwood, Mass. 1969 THE GOOD SHEPHERD Memorial window at the First Baptist Church, Mansfield, Mass. ''In memory of Deacon Pierpont M. Edwards and Susan Fuller Edwards'' Dedicated J u1y 1914 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Historical Sketches . 1 Early History of Salem . 1 Early History of Rehoboth . 3 II. Roberti Fuller, ca. 1615 - 1706 . 17 Original Rehobo~h Land Records concerning Roberti Fuller . 48 Recorded Deeds of Robertl Fuller . 60 Recorded Deeds of Robert and Margaret Fuller . 66 The Bowen Family of Early Rehoboth . 73 III. Samuel2 Fuller, ca. l 649 - 1724 . 77 Samuel's Estate . 81 Ide Family of Early Rehoboth . 86 IV. Samue13 Fuller, 1676 - 1724 . 87 Estate of Samuel3 Fuller . 96 Land Owned by Samuel3 Fuller .... _. 108 Wilmarth Family of Early Rehoboth . 117 V. Timothy4 Fuller, 1710/11 - 1782 ................ 121 Timothy's Estate . 144 Land Transactions of Timothy4 Fuller ........... 159 Recorded Deeds of Timothy4 Fuller . 165 Hannah Bliss and Her Father's Estate ............ 172 Bliss Family of Early Rehoboth ................ 176 Notes on the Thurber Family Genealogy . 180 VI. Timothy5 Fuller, 175 l - 1809 .................. 184 Estate of His Mother, Elizabeth (Thurber) Fuller ... 191 Settlement of Timothy's Estate . 196 Land Transactions of Timothy5 Fuller . 21 O Notes on the Medbury Family ................. 220 V vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Vil. Timothy6 Fuller, 1799 - 1866 .................. 222 Timothy's Estate .......................... -

Rhode Island

1 THE SEWER OF NEW ENGLAND “History ... does not refer merely to the past ... history is literally present in all that we do.” — James Baldwin, 1965 “UNNAMEABLE OBJECTS, UNSPEAKABLE CRIMES” NOTE: During the early period “Rhode Island” was an ambiguous designator, as it might refer to the moderately sized island in Narragansett Bay, or it might refer to the entire colony of which said island was a part, together with the extensive Providence Plantations on the mainland shore. Also, since that period, there have been significant trades of land and towns between Rhode Island and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts — such as the entire city of Fall River. GO BACK TO THE PREVIOUS PERIOD 1. This was the opinion of the Reverend Cotton Mather, who actually did know a thing or two about sewage. HDT WHAT? INDEX RHODE ISLAND ROGUE ISLAND 17TH CENTURY 1650 Thomas Angell was a member of the Town Council in Providence and surveyor and commissioner, and one of six jurymen. The settlers in Rhode Island, who had not yet been able to reimburse Roger Williams with the agreed sum of £100 for his trip to England to secure them their charter, at this point needed to persuade him to return to England and appear before the Committee on Plantations and represent their interests. To get him again to go, they pledged that they would indeed pay this three-year-old debt, and would pay in addition another £100. They would not, however, be able to advance him any money for the voyage and for his family to live on during his absence, so Williams at this point sold his trading house. -

The Blackstone River

A partnership of member organizations, the Blackstone River Coalition seeks to restore and protect water quality and wildlife habitat in the river corridors, and to advocate for sound land use in the Blackstone River watershed, which stretches from the brooks that form its headwaters in Worcester, MA, to its mouth in Pawtucket, RI. THE BLACKSTONE RIVER~ CLEAN BY 2015 The Blackstone River Coalition is a non-profit organization partnering with numerous organizations working together to restore the Blackstone River and to improve the health of the Blackstone River watershed. We invite you to join us to help make the Blackstone River fishable and swimmable by 2015. Special thanks to the following for their contributions to this publication: Therese Beaudoin, Mass DEP; Peter Coffin, BRC; Tammy Gilpatrick, BRC; Cindy Delpapa, Mass Riverways Program, Department of Fish and Game; Alan Libby and Veronica Masson, RIDEM Division of Fish and Wildlife; Mauri Pelto, Nichols College; and Donna Williams, Mass Audubon. Blackstone River Coalition BRC STAFF P.O. Box 70477, Worcester MA 01607 Peter Coffin, Coordinator, BRC 508-753-6087 [email protected] www.zaptheblackstone.org Tammy Gilpatrick, Coordinator, BRC Watershed-wide Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring Program [email protected] COALITION PARTNERS BLACKSTONE HEADWATERS COALITION JOHN H. CHAFEE BLACKSTONE RIVER VALLEY SAVE THE BAY / SAVE THE BAY CENTER PO BOX 70688, QUINSIGAMOND VILLAGE NATIONAL HERITAGE CORRIDOR 100 SAVE THE BAY DRIVE, PROVIDENCE, RI 02905 WORCESTER, MA 01607 -

Transatlantic Print Culture and the Rise of New England Literature, 1620-1630

TRANSATLANTIC PRINT CULTURE AND THE RISE OF NEW ENGLAND LITERATURE 1620-1630 by Sean Delaney to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of History Northeastern University Boston, MA April 2013 1 TRANSATLANTIC PRINT CULTURE AND THE RISE OF NEW ENGLAND LITERATURE 1620-1630 by Sean Delaney ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate School of Northeastern University, April 2013 2 Transatlantic Print Culture And The Rise Of New England Literature 1620-1630 Despite the considerable attention devoted to the founding of puritan colonies in New England, scholars have routinely discounted several printed tracts that describe this episode of history as works of New England literature. This study examines the reasons for this historiographical oversight and, through a close reading of the texts, identifies six works written and printed between 1620 and 1630 as the beginnings of a new type of literature. The production of these tracts supported efforts to establish puritan settlements in New England. Their respective authors wrote, not to record a historical moment for posterity, but to cultivate a particular colonial reality among their contemporaries in England. By infusing puritan discourse into the language of colonization, these writers advanced a colonial agenda independent of commercial, political and religious imperatives in England. As a distinctive response to a complex set of historical circumstances on both sides of the Atlantic, these works collectively represent the rise of New England literature. 3 This dissertation is dedicated with love to my wife Tara and to my soon-to-be-born daughter Amelia Marie. -

Johnson's Wonder-Working Providence, 1628-1651;

ORIGINAL NARRATIVES OF EARLY AMERICAN HISTORY REPRODUCED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION General Editor, J. FRANKLIN JAMESON, Ph.D., LL.D. DIRECTOR OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH IN THE CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON JOHNSON'S WONDER-WORKING PROVIDENCE 1628 — 1651 TITLE-PAGE OF THE "WONDER-WORKING PROVIDENCE" From a copy of the original in the Woburn Public Library ORIGINAL NARRATIVES OF EARLY AMERICAN HISTORY JOHNSON'S WONDER - WORKING PROVIDENCE 1628-1651 / n n EDITED BY J. FRANKLIN JAMESON, Ph.D., LL.D. DIRECTOR OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH IN THE CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON WITH A MAP AND TWO FACSIMILES CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS NEW YORK Copyright, 1910, by CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the permission of Charles Scribner's Sons Sag, IS A. CONTENTS JOHNSON'S WONDER-WORKING PROVIDENCE OF SIONS SAVIOUR IN NEW ENGLAND—"HISTORY OF NEW ENGLAND" Edited by J. Franklin Jameson VAOX Introduction 3 To the Reader 21 Book I. The Sad Condition of Old England 23 The Call of Christ's People to New England; their Churches . 25 The Demeanor of their Church Officers 26 The Demeanor of the People 28 Their Civil Government; the Maintenance of the First Table . 30 Their Care for Warlike Discipline 33 Their Liberty; their Charter; their Means 36 The Massachusetts Indians . .39 The Pestilence 40 The Men of Plymouth and the Indians 42 John Endicott 44 The Settlement of Salem 45 The Founding of the Salem Church; Mr. -

History of Boston Harbor

History of Boston Harbor Boston Harbor has always played an important role in the history of New England. Over 350 years ago, early settlers were drawn to the region largely because of its fine natural port. Boston Harbor quickly became New England's gateway to markets both at home and abroad. Today, harbor commerce annually generates $8 billion in revenue for the region. One of America 's oldest and most active ports, the harbor is at once an avenue of trade and transportation, a haven for sport and recreation and potentially a rich fishing ground. Boston Harbor comprises an area of some 50 square miles bounded by 180 miles of shore line dotted with 30 islands covering about 1,200 acres of lard. During the 1990s, the harbor will be repaid for centu- Native Americans ries of service to New England through the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority's $6.1 billion program to clean When the first jjermanent English settlers arrived in up Boston Harbor with pollution control facilities, includ- the region, about 15,000 Native Americans lived along the ing the nation's second-largest sewage treatment plant. coast from Boston to Salem, in some 26 villages. Recent The systematic abuse and pollution of 350 years will cease research shows that they traded over great distances: the when the completion of new wastewater treatment stone parts of axes excavated by archaeologists in facilities brings an end to the daily discharge of untreated Charlestown probably came from Pennsylvania. Native or poorly treated sewage into the harbor. Given an Americans cultivated com along the shore and on the opportunity to cleanse and restore itself, the harbor will harbor islands, harvested lobsters and fish and hunted again resemble the natural resource that beckoned the deer. -

Facts About History : Boston Harbor

* UM ASS/ AMHERST * 1999 Facts about N0 V 02 M 312Dbb D2t1 bDb3 7 Massachusetts History: Boston A Massachusetts Water Resources Authority Publication - Fall 1996 Harbor has long played an During the 1990s, Boston Harbor will be Boston restored as one of New England's finest harbors important role in the history of New through the Massachusetts Water Resources England. Over 350 years ago, settlers Authority's $3.4 billion program to protect Boston Harbor with pollution control facilities, including were drawn to the region largely because of its the nation's second-largest sewage treatment plant. fine natural harbor. Boston Harbor quickly became The completion of new wastewater treatment New England's gateway to markets both at home facilities will bring to an end the daily discharge of poorly treated sewage into the harbor that went and abroad. Today, harbor commerce generates unchecked for centuries. $8 billion annually in revenue for the region. Given an opportunity to cleanse itself, the One of America's most active ports, the harbor harbor will again resemble the natural resource offers an avenue of trade and transportation, a that attracted the original settlers. A restored Boston Harbor will offer recreational and haven for sport, recreation and tourism and a commercial benefits to future generations. fertile fishing ground. Boston Harbor comprises an Current proposals to include Boston's harbor area of some 50 square miles, bounded by 180 islands in the National Park system could add a welcome finishing touch to MWRA's investment in miles of shoreline dotted with 30 islands totaling sewerage infrastructure. -

Rhode Island

1 THE SEWER OF NEW ENGLAND “History ... does not refer merely to the past ... history is literally present in all that we do.” — James Baldwin, 1965 “UNNAMEABLE OBJECTS, UNSPEAKABLE CRIMES” NOTE: During the early period “Rhode Island” was an ambiguous designator, as it might refer to the moderately sized island in Narragansett Bay, or it might refer to the entire colony of which said island was a part, together with the extensive Providence Plantations on the mainland shore. Also, since that period, there have been significant trades of land and towns between Rhode Island and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts — such as the entire city of Fall River. 1. This was the opinion of the Reverend Cotton Mather, who actually did know a thing or two about sewage. HDT WHAT? INDEX RHODE ISLAND ROGUE ISLAND 11,500 BCE Toward the end of the last Ice Age, most of what is now New England was still under an immense sheet of very slowly melting ice, like a mile in thickness, retreating from an edge that at one point had reached as far south as New Jersey. Vegetation was appearing on exposed surfaces: mainly tundra plants such as grasses, sedge, alders, and willows. NEW ENGLAND However, nearly all areas of the globe had climates at least as warm and moist as today’s. 10,500 BCE In this “Paleo Period,” humans began to occupy the New England region sparsely, hunting mastodon and caribou. Spruce forests began to appear, followed by birch and pine. This period would last to about 8,000 BCE. NEW ENGLAND The beginning of the Younger Dryas.