What Is Game Studies in Australia?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God Games’, with the Player Supposedly Given Omnipotent Control Over the Game Environment, Revealing the Enduring Presence of the Second-Creation Narrative

Smith, B. T. L. (2017). Resources, Scenarios, Agency: Environmental Computer Games. Ecozon@, 8(2), 103-120. http://ecozona.eu/article/view/1365 Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Universidad de Alcale at http://ecozona.eu/article/view/1365 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Resources, scenarios, agency: environmental computer games Abstract In this paper I argue that computer games have the potential to offer spaces for ecological reflection, critique, and engagement. However, in many computer games, elements of the games’ procedural rhetoric limit this potential. In his account of American foundation narratives, environmental historian David Nye notes that the ‘second-creation’ narratives that he identifies “retain widespread attention [...] children play computer games such as Sim City, which invite them to create new communities from scratch in an empty virtual landscape…a malleable, empty space implicitly organized by a grid” (Nye, 2003). I begin by showing how grid-based resource management games encode a set of narratives in which nature is the location of resources to be extracted and used. I then examine the climate change game Fate of the World (2011), drawing it into comparison with game-like online policy tools such as the UK Department for Energy and Climate Change’s 2050 Calculator, and models such as the environmental scenario generation tool Foreseer. -

7:30 A.M. – AUDIT CONFERENCE PARK COMMISSIONERS and PARK DISTRICT AUDIT COMMITTEE (Pursuant to Section 121.22 (D) (2) of the Ohio Revised Code)

BOARD OF PARK COMMISSIONERS OF THE CLEVELAND METROPOLITAN PARK DISTRICT THURSDAY, MARCH 14, 2019 Cleveland Metroparks Administrative Offices Rzepka Board Room 4101 Fulton Parkway Cleveland, Ohio 44144 7:30 A.M. – AUDIT CONFERENCE PARK COMMISSIONERS AND PARK DISTRICT AUDIT COMMITTEE (Pursuant to Section 121.22 (D) (2) of the Ohio Revised Code) 8:00 A.M. – REGULAR MEETING AGENDA 1. ROLL CALL 2. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE 3. MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING FOR APPROVAL OR AMENDMENT • Regular Meeting of February 14, 2019 Page 88339 4. FINANCIAL REPORT Page 01 5. NEW BUSINESS/CEO’S REPORT a. APPROVAL OF ACTION ITEMS i) General Action Items (a) Chief Executive Officer’s Retiring Guest(s): • Terry L. Robison, Director of Natural Resources Page 07 • Stephen J. Schulz, Education Specialist Page 08 • Virginia G. Viscomi, Service Maintenance II Page 08 (b) 2019 Budget Adjustment No. 2 Page 09 (c) Revision of Rates and User Fees Page 10 (d) Club Metro 2019 Financial Request Page 10 (e) RFP #6149: Golf Cars Page 11 (f) Edgewater Marina Operations – Lease Agreement Page 12 (g) Whiskey Island Marina Operations – Management Services Agreement Page 14 (h) Branded Product Sponsor and Suppler of Beverages Agreement – Page 15 Amendment No. 2 (i) Contract Amendment – RFP #6344-B: Bonnie Park Ecological Restoration Page 16 and Site Improvement Project – Mill Stream Run Reservation -GMP 1 (j) Professional Services Agreement – RFQu #6402: Bridge Inspection and Page 18 Engineering Support Program 2019-2014; and 2020 Bridge Inspections and Summary Reports Proposal (k) Authorization of Funds – Whiskey Island Marina Emergency Repair – Page 21 Wind Damage (l) Nomination of Joseph V. -

DEMO Magazine

ISSUE 18 SPRING/SUMMER 2013 DEMOThe Alumni Magazine of Columbia College Chicago The avant-garde fashion designs of AGNES HAMERLIK Revitalizing Detroit with PHILLIP COOLEY Lessons learned on KICKSTARTER May 17, 2013 ALUMNI AT Want to perform? Volunteer? Or just come out and be a part of the awesome Manifest audience? If you are an alumnus and would like an application to perform on the Alumni Stage, contact Cyn Vargas at [email protected]. Stop by, sit back, and ALUMNI LOUNGE relax in our alumni ALUMNI & lounge! You'll enjoy your Noon – 7PM fellow alumni performers GRADUATION PARTY singing, reciting, dancing, 623 South Wabash and other cool stuff. 8PM – 11PM Quincy Wong Center Hilton Chicago for Artistic Expression 720 S. Michigan Ave. Grand Ballroom colum.edu/alumnimanifest Art: Thumy Phan, Manifest Creative Director Creative Phan, Manifest Art: Thumy ’12) Jacob Boll (BA Photos: CONTENTS DEMO ISSUE 18 SPRING/SUMMER 2013 18 11 FEATURES PORTFOLIO SPOT ON DEpaRTMENTS 8 22 30 Justin “Nordic Thunder” 03 Vision A question for Howard (BA ’07) reigns as President Carter KICKSTART MY ART LIFE DURING king in the competitive world Columbia alumni, students, WARTIME of air guitar. 04 Wire News from the and faculty share lessons Photographer Andrew Nelles Columbia community learned on their way to crowd- (BA ’08) recounts his days 32 Karine Saporta (BA ’72), funding success. covering American troops in knighted in France, 38 Alumni News & Notes By Stephanie Ewing (MA ’12) Afghanistan. As told to Andrew stays in demand as a Featuring class news, notes, Greiner (BA ’05) dancer, choreographer, and networking 14 and photographer. -

Vlaams Audiovisueel Fonds

VLAAMS AUDIOVISUEEL FONDS . jaarverslag 2018 VLAAMS AUDIOVISUEEL FONDS . jaarverslag 2018 uitgegeven door het .VLAAMS AUDIOVISUEEL FONDS vzw huis van de vlaamse film bischoffsheimlaan 38 - 1000 brussel [email protected] vaf.be Met de steun van de Vlaamse minister van Cultuur, Media, Jeugd en Brussel en de Vlaamse minister van Onderwijs INHOUD . jaarverslag 2018 VOORWOORDEN FINANCIEEL CREATIE TALENT- ONTWIKKELING •4 •7 •15 •26 COMMUNICATIE & PUBLIEKSWERKING GAMEFONDS SCREEN PROMOTIE FLANDERS •39 •47 •53 •67 DUURZAAM KENNISOPBOUW WERKING VLAAMSE FILM FILMEN IN CIJFERS •73 •77 •81 •89 Toen ik in mei vorig jaar op het Festival Deze maatregelen zullen ongetwijfeld om op dit vlak lessen te trekken. van Cannes de film Girl te zien kreeg, hun vruchten afwerpen. Toch wil ik een Het is duidelijk dat we erin geslaagd zijn voelde ik aan de stilte in de zaal bij warme oproep doen aan de volgende om ook dit jaar als VAF op verschillende de aftiteling welke magie er uitging Vlaamse Regering voor extra middelen vlakken toonaangevend te zijn. Hopelijk VOORWOORD van het brengen van zo’n mooi en in de nieuwe bestuursperiode. Er kunnen we in de toekomst op dit elan ontroerend verhaal. De tsunami aan werden in het verleden reeds extra doorgaan. Met het huidige team van Alles start met een prijzen die de film in ontvangst mocht middelen vrijgemaakt voor het VAF/ medewerkers heb ik er als voorzitter nemen, was ongezien. We mogen als Mediafonds en het VAF/Gamefonds die alvast het volste vertrouwen in. n goed verhaal VAF bijzonder fier zijn dat we mee aan zeker een boost gegeven hebben. -

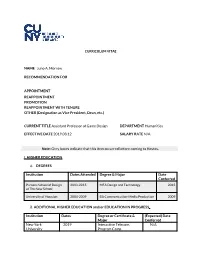

NAME Juno A. Morrow RECOMMENDATION FOR

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME Juno A. Morrow RECOMMENDATION FOR APPOINTMENT REAPPOINTMENT PROMOTION REAPPOINTMENT WITH TENURE OTHER (Designation as Vice President, Dean, etc.) CURRENT TITLE Assistant Professor of Game Design DEPARTMENT Humanities EFFECTIVE DATE 2019.08.12 SALARY RATE N/A Note: Grey boxes indicate that this item occurred before coming to Hostos. I. HIGHER EDUCATION A. DEGREES Institution Dates Attended Degree & Major Date Conferred Parsons School of Design 2013-2015 MFA Design and Technology 2015 at The New School University of Houston 2004-2009 BA Communication-Media Production 2009 B. ADDITIONAL HIGHER EDUCATION and/or EDUCATION IN PROGRESS Institution Dates Degree or Certificate & (Expected) Date Major Conferred New York 2019 Interactive Telecom. N/A University Program Camp II. EXPERIENCE A. TEACHING EXPERIENCE Institution Department Rank Dates CUNY—Eugenio María de Hostos Humanities Assistant Professor 2015- Community College Present Parsons School of Design Art, Media & Technology Part-time Lecturer 2015 Parsons School of Design Art, Media & Technology Teaching Fellow 2014 Parsons School of Design Art, Media & Teaching Assistant 2014 Technology B. OTHER EXPERIENCE Institution Department Rank or title role Dates (Independent/Freelance) N/A Photographer/Designer 2009- Present Try The World N/A Front-End Web Developer 2015 Parsons School of Design gadgITERATION Graduate Research 2014-2015 Assistant Reed Elsevier Universal Access Research Coordinator 2012-2013 HASH magazine Photography Staff Photographer 2012-2013 HRP/CoxReps -

Biden Calls for New Gun Laws As Shootings Rekindle Debate

P2JW083000-6-A00100-17FFFF5178F ****** WEDNESDAY,MARCH 24, 2021 ~VOL. CCLXXVII NO.68 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 32423.15 g 308.05 0.9% NASDAQ 13227.70 g 1.1% STOXX 600 423.31 g 0.2% 10-YR. TREAS. À 13/32 , yield 1.637% OIL $57.76 g $3.80 GOLD $1,724.70 g $13.10 EURO $1.1851 YEN 108.58 Boulder Mourns Victims as Suspect Is ChargedWith Murder Intel Sets What’s News Strategy To Speed Business&Finance Its Chip ntel’snew CEO is fast Itracking effortstorevive the semiconductor giant Revival with abroad plan that mixes increased outsourcing with acommitment to spend $20 Semiconductor maker billion on newfactories. A1 earmarks $20 billion Powell, in a joint appear- ancewith Yellen on Capitol GES to expand U.S. plants, Hill, said he doesn’t expect IMA will boost outsourcing the $1.9trillion stimulus package will lead to an unwel- GETTY SE/ BY AARON TILLEY come increase in inflation. A2 U.S. stocks ended lower Intel Corp.’snew chief exec- afterthe testimonybyPowell ANCE-PRES utiveisfast tracking effortsto FR and Yellen, with the S&P 500, revivethe semiconductor gi- Dowand Nasdaq losing 0.8%, ENCE ant with abroad plan that AG 0.9% and 1.1%, respectively. B11 Y/ mixes increased outsourcing with acommitment to spend Robinhood Marketsfiled NNOLL $20 billion on newfactories paperworkwith the SEC for CO that could help addressa what is suretobeone of the ON global chip shortage. year’s most eagerly awaited JAS IN MEMORY: People gather foracandlelight vigil Tuesdaynight to honor the 10 victims killedMondaybyagunman at a Pat Gelsinger said Tuesday initial public offerings. -

Bowl Round 8

USABB National Bowl 2016-2017 Round 8 Round 8 First Half (Tossup 1) This leader's eunuch Zhao Gao managed to alter the line of succession by convincing this leader's son Fusu to commit suicide. This man was advised by Li Si, who inspired him to target the Hundred Schools of Thought, bury (*) Confucian scholars alive, and burn their teachings. This man defeated the state of Zhao to end the Warring States period in 221 BC. A large terracotta army was designed for the burial tomb of, for ten points, what first emperor of China and founder of the Qin [chin] dynasty? ANSWER: Qin Shi Huangdi (accept Ying Zheng or Zhao Zheng) (Bonus 1) This man consolidated power over Italy with his blackshirts in the March on Rome. For ten points each, [Part A] Name this leader of Italy before and during World War II, nicknamed \Il Duce." ANSWER: Benito Mussolini [Part B] Mussolini was a proponent of this far-right political ideology, which emphasizes the state over the individual via an authoritarian ruler. ANSWER: fascism (accept word forms) [Part C] Mussolini established Italian East Africa after his conquest of this country in 1936, which had been ruled at the time by Haile Selassie. ANSWER: Ethiopia (accept Abyssinia) (Tossup 2) A character in this story brings home an invitation to Georges Rampouneau's [rom-poo-NOH's] party, and sleeps in a side room while his wife dances until four in the morning. The central object of this story is only worth five hundred francs, but the (*) Loisels [lwah-ZELLS] nevertheless incur massive debt in order to repay Madame Forestier [foh-res-tee-AY] when that object is lost at a ball. -

Formatting Guide: Colors & Fonts

MOBILE M&A AND VALUATION UPDATE Q2 2017 BOSTON CHICAGO LONDON LOS ANGELES NEW YORK ORANGE COUNTY PHILADELPHIA SAN DIEGO SILICON VALLEY TAMPA CONTENTS Section Page Introduction . Research Coverage: Mobile 3 . Key Takeaways 4-5 M&A Activity & Multiples . M&A Dollar Volume 7 . M&A Transaction Volume 8-10 . LTM Revenue Multiples 11-12 . Revenue Multiples by Segment 13 . Highest Revenue Multiple Transaction for LTM 14 . Notable M&A Transactions 15 . Most Active Buyers 16 Public Company Valuation & Operating Metrics . Mobile 115 Public Company Universe 18-20 . Recent IPOs 21 . Stock Price Performance 24 . LTM Revenue, EBITDA & P/E Multiples 25-27 . Revenue, EBITDA & EPS Growth 28-30 . Margin Analysis 31-32 . Best / Worst Performers 33-34 Notable Transaction Profiles 35-40 Public Company Trading & Operating Metrics 41-46 Technology & Telecom Team 47 1 INTRODUCTION RESEARCH COVERAGE: MOBILE Capstone’s Technology & Telecom Group focuses its research efforts on the follow market segments: MOBILE & WIRELESS SAAS & CLOUD CONSUMER INTERNET • App Stores & Content Aggregators • Carrier Back Office • Games / Virtual Goods • M-Commerce Enablement • Messaging & VoIP • Mobile / Local Marketing • Mobile Devices CONSUMER IT & E-COMMERCE • Mobile OS & Utility SW TELECOM HARDWARE • Mobility & Monitoring • Portals & Social Networks • Search & Referral - Diversified • Travel & Entertainment • Vertical Market • Video, Music & eBooks 3 KEY TAKEAWAYS – M&A ACTIVITY & MULTIPLES LTM M&A dollar volume decreased to $52.5B, just shy of the five-year high of -

Conference Booklet

30th Oct - 1st Nov CONFERENCE BOOKLET 1 2 3 INTRO REBOOT DEVELOP RED | 2019 y Always Outnumbered, Never Outgunned Warmest welcome to first ever Reboot Develop it! And we are here to stay. Our ambition through Red conference. Welcome to breathtaking Banff the next few years is to turn Reboot Develop National Park and welcome to iconic Fairmont Red not just in one the best and biggest annual Banff Springs. It all feels a bit like history repeating games industry and game developers conferences to me. When we were starting our European older in Canada and North America, but in the world! sister, Reboot Develop Blue conference, everybody We are committed to stay at this beautiful venue was full of doubts on why somebody would ever and in this incredible nature and astonishing choose a beautiful yet a bit remote place to host surroundings for the next few forthcoming years one of the biggest worldwide gatherings of the and make it THE annual key gathering spot of the international games industry. In the end, it turned international games industry. We will need all of into one of the biggest and highest-rated games your help and support on the way! industry conferences in the world. And here we are yet again at the beginning, in one of the most Thank you from the bottom of the heart for all beautiful and serene places on Earth, at one of the the support shown so far, and even more for the most unique and luxurious venues as well, and in forthcoming one! the company of some of the greatest minds that the games industry has to offer! _Damir Durovic -

Next-Up in NBA 2K20: Make Way for the WNBA

Next-up in NBA 2K20: Make way for the WNBA August 8, 2019 All 12 WNBA Teams and More Than 140 Players are Ready to Play on September 6 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Aug. 8, 2019-- 2K today announced all 12 WNBA teams and more than 140 players are making their debut in NBA® 2K20, the next iteration of the top-rated and top-selling NBA video game simulation series of the past 18 years*. Available in Play Now and Season modes, fans of the franchise will be able to take control of their favorite WNBA players for the first time and experience gameplay animations, play styles and visuals built exclusively around the women’s game. “Growing up, I always remembered watching male athletes on TV and playing as them in video games. Now, to have the WNBA be in the position we are and to have women featured prominently in NBA 2K20, we are allowing young girls and boys to have female athletes as role models,” said Candace Parker, Los Angeles Sparks forward. “The 2K team has done an amazing job of making sure to not just put women into the game playing men’s basketball, but I’ve seen first-hand the hard work they’re doing to make this as real and authentic as possible to women’s basketball. I’m proud to be a part of this team paving the way for the future.” Many of the top WNBA superstars, like Parker and A’ja Wilson of the Las Vegas Aces, have been scanned into NBA 2K20 earlier this year using our best-in-class motion capture technology to create the most realistic simulation on the market. -

Revolutionary High-Flyer and Globally Beloved Legend Announced As

Revolutionary high-flyer and globally beloved legend announced as the first of two playable pre- order characters in upcoming edition of flagship WWE video game franchise NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- 2K today announced that former WWE Champion, Rey Mysterio, will return to virtual WWE action – for the first time in four years – through WWE® 2K19, the forthcoming release in the flagship WWE video game franchise. The revolutionary luchador and “Master of the 619” – who routinely overcame insurmountable odds and established himself as one of the most popular Superstars in WWE history – will appear in WWE 2K19 as a playable character wearing ring gear reflective of his surprise appearance in the 2018 Royal Rumble. Mysterio, alongside a second playable character to be announced by 2K in the coming weeks, will be available as bonus content for those who pre-order the game at participating retailers for the PlayStation®4 computer entertainment system, the Xbox One family of devices including the Xbox One X and Windows PC. WWE 2K19 is currently scheduled for worldwide release on October 9, 2018, with Early Axxess players receiving their copies and in-game bonuses beginning four days early on October 5, 2018. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180626005295/en/ 2K today announced that former WWE Champion, Rey Mysterio, will return to virtual WWE action – for the first time in four years – through WWE® 2K19, the forthcoming release in the flagship WWE video game franchise. (Photo: Business Wire) “Since my WWE debut in 2002, ‘Never Say Never’ – the WWE 2K19 campaign theme – has been a big part of my career,” said Mysterio. -

Lohanvtake-Two-Res-Take-Two-Brf

To be Argued by: JEREMY FEIGELSON (Time Requested: 30 Minutes) APL-2017-00028 New York County Clerk’s Index No. 156443/14 Court of Appeals of the State of New York LINDSAY LOHAN, Plaintiff-Appellant, – against – TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC., ROCKSTAR GAMES, ROCKSTAR GAMES, INC. and ROCKSTAR NORTH, Defendants-Respondents. BRIEF FOR DEFENDANTS-RESPONDENTS JEREMY FEIGELSON JARED I. KAGAN ALEXANDRA P. SWAIN DEBEVOISE & PLIMPTON LLP Attorneys for Defendants-Respondents 919 Third Avenue New York, New York 10022 Tel.: (212) 909-6000 Fax: (212) 909-6836 Date Completed: May 31, 2017 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Defendant-Respondent Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. is the parent company of Defendant-Respondents Rockstar Games, Inc. and Rockstar North Limited. The following companies also are subsidiaries of Defendant-Respondent Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc.: 2K Australia Pty. Ltd.; 2K Czech, s.r.o.; 2K Games (Chengdu) Co., Ltd.; 2K Games (Hangzhou) Co. Ltd.; 2K Games (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.; 2K Games, Inc.; 2K, Inc.; 2K Marin, Inc.; 2K Play, Inc.; 2K Games Songs LLC; 2K Games Sounds LLC; 2K Games Tunes LLC; 2K Vegas, Inc.; 2KSports, Inc.; A.C.N. 617 406 550 Pty Ltd.; Cat Daddy Games, L.L.C.; Digital Productions S.A.; DMA Design Holdings Limited; Double Take LLC; Firaxis Games, Inc.; Frog City Software, Inc.; Gathering of Developers, Inc.; Gearhead Entertainment, Inc.; Indie Built, Inc.; Inventory Management Systems, Inc.; Irrational Games, LLC; Jack of All Games Norge A.S.; Jack of All Games Scandinavia A.S.; Joytech Europe Limited; Joytech Ltd.; Kush Games, Inc.; Maxcorp Ltd.; Parrot Games, S.L.U.; Rockstar Events Inc.; Rockstar Games Songs LLC; Rockstar Games Sounds LLC; Rockstar Games Toronto ULC; Rockstar Games Tunes LLC; Rockstar Games Vancouver ULC; Rockstar Interactive India LLP; Rockstar International Limited; Rockstar Leeds Limited; Rockstar Lincoln Limited; Rockstar London Limited; Rockstar New England, Inc.; Rockstar San Diego, Inc.; Social Point, K.K.; Social Point, S.L.; T2 Developer, Inc.; Take 2 i Interactive Software Pty.